Auvers-sur-Oise, 2006

‘Vincent van Gogh, et Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec,’ the patronne says firmly, and proudly, when I ask who are the men in the old photograph on the wall. My heart leaps – an unknown photograph of the mature Vincent? Only one is known, blurry and from the back. Vincent refused to be photographed, embarrassed by his appearance, but also distrustful of the dishonesty, the incompleteness of the photograph. (When he was sent a photograph of his mother, he immediately painted her portrait, as if needing the veracity of a painting.) And what chance of it turning up in this quirky old restaurant, four tables crammed into a living room, every inch of the walls covered in hand-painted murals, and copies of Vincent’s paintings? Perhaps he ate here? Even painted the murals …? Strange things happen to you on the Vincent trail, weird imaginings. He is always present in the places he was.

This is the only place I’ve never visited in 45 years of Vincent-following. Auvers-sur-Oise. Where he lived the last seventy days of his life, painted 74 pictures, and died, on his body an unfinished letter to his brother Theo, ‘Well, I have risked my life for my work, and it has cost me half my reason’. And my visit here by happenstance – an unexpected free day in a Paris holiday, and discovering that Auvers is an hour away by train.

Of course it’s neither of the great artists – the shorter of the two no dwarf (Lautrec was in fact almost 5 feet tall) but sitting down, the photograph cropped. But the patronne, who has run her restaurant here for 45 years, has served me a sumptuous country meal of rabbit cooked in pears, with creamy mashed potatoes and crisp cabbage served as separate courses, personally, and she is proud of this dining room, full of her life. I say, ‘formidable’, thank her, and pay the bill.

Vincent arrived at Auvers in May 1890, after leaving the asylum in St-Remy, convinced that it was making him ill rather than curing him. In fact he had worked well there, producing much of his best work; but in the last few months he was going out less, painting from other artists’ work rather than direct from the motif.

A brief stay in Paris, meeting fellow painters, had overwhelmed him. And his first meeting with Theo’s wife, Jo, and their baby, Vincent, brought home to him the reality of Theo’s situation.

On Pissarro’s recommendation he came to Auvers, where his health could be monitored by Dr Gachet, a homeopathic doctor and art enthusiast (although, according to Vincent, ‘as mad as me’), who had bought canvases from Pissarro and Cézanne when they had painted locally in 1870s.

Another cheap room – he rejects the 6 franc room Gachet had selected, finds himself one at 3 francs 50 – I work like a labourer, so I should pay labourer’s rates, he wrote to Theo. And he worked like a labourer – landscapes, rural scenes, houses, gardens, buildings, flowers, portraits. With no studio, living in a tiny attic room. Mostly not his best work, but pictures that would have sold if he had a ready market. And he was beginning to be known, to be exhibited, to sell. (It is important to remember that neither Gauguin and Cézanne, both older and more experienced artists, could make a living as artists at this time. Cézanne’s ‘breakthrough’ came when he was 55, Gauguin’s, after his death at 54.)

Vincent had gone to Arles in February 1888, because ‘the painter of the future is a colourist such as there has never been before,’ he writes to Theo, ‘and we have to do what our means allow us in that direction, without having doubts and without flinching.’ And this has to be in ‘Japan in the South’, where the light is strong and clear, and the colours bright enough to sustain the vision of the twenty worthwhile artists, as he writes to his sister, the Impressionists. The new art will be collective, because the needs of the new art, to be comparable with German music and French writing, will ’exceed the power of an isolated individual, and will therefore probably be created by groups of men combining to carry out a shared idea,’ he writes to Bernard. And therefore he will found his Studio of the South, for those twenty artists. (He even buys 12 chairs, for his tiny four-room house, as if imagining the disciples there. With Gauguin at their head.)

Vincent had always been (was always) intensely lonely, an individual surrounded by an uncrossable emptiness between himself and others. As such ‘types’ (Outsiders) do, he had attempted to fill/cross that emptiness, with sudden changes in direction and location, passionate identification with causes, and intense amour fous with unfortunate women.

In his ‘religious phase’, age 23 he gave his only sermon, at a Methodist mission church in Richmond. His text was “I am a stranger on the earth. Hide not thy commandments from me”. Here are some extracts from the sermon:

‘Our life is a pilgrim’s progress.’ ‘we are pilgrims on the earth and strangers – we come from afar and we are going far.’ ‘We may not live casually hour to hour – no, we have a strife to strive and a fight to fight.’ ‘I once saw a beautiful picture: it was a landscape at evening. In the distance on the right-hand side a row of hills appeared blue in the evening mist. Above those hills the splendour of the sunset, the grey clouds with their linings of silver and gold and purple. The landscape is a plain or heath covered with grass and with yellow leaves, for it was autumn. Through the landscape a road leads to a high mountain far, far away, on the top of that mountain is a city wherein the setting sun casts glory. On the road walks a pilgrim. He has walked for a good long while already, and he is very tired.’

Having lost his religious faith, Vincent substituted a belief in art. The celestial city is now Japan in the South. The community of a church congregation is now the community of the artists of the petit boulevard. The new art will be communal. Meanwhile, he is the pilgrim, leading the way. Alone. He is walking a narrow path, ever outward, into the unknown. He acknowledges in a letter to his sister that there is ‘not any chance of my coming back to Holland’.

In sixteen months in Arles he paints 147 paintings, many of his most famous, and finest. And, years later, the most expensive. All the time worrying about the cost to Theo. (Theo is paying him 150 francs a month out of his salary at Boussods.) He insist that all the paintings are Theo’s, and hopes that one day Theo the dealer will make his ‘investment’ back. Theo, having subsidised him for seven years, sees little likelihood of this.

Spring arrives, and he is out every day, pegging his easel down in the fierce cold mistral wind (that sweeps the air clean to an even greater clarity – I have experienced it), painting the successively blossoming fruit trees, almond, peach, apricot, pear, 17 paintings in less than a month. He paints himself to exhaustion. And then it is the harvest, painting all day in the summer sun. Also a Dutch-built lifting bridge, painted many times, in the hope of interesting buyers in Holland. Flower studies – especially sunflowers. And portraits, mainly of the Roulin family. Often he is so exhausted he cannot even write the letters that are his one form of communication. For he is intensely lonely, cut off from the suspicious closed community by language, his thick accent, their patois, Roulin the postal employee at the station his only friend.

Meanwhile there are problems in Paris. Theo is in dispute with his employers, and may lose his job. Then he is diagnosed with syphilis. Vincent says he will give up painting if it helps Theo. And the next day takes out a lease on the Yellow House. Yellow the colour of Japan. He has the house painted a more vivid yellow, has it updated and gas installed, his Studio of the South. Fortunately Theo has a bequest from Uncle Cent – whose will specifically excluded Vincent, the only one in the family excluded. And meanwhile he pressures Theo to pay Gauguin to come and live with him.

It is a disaster. Strong contrary characters, stuck in the tiny cottage in autumn rains. So much for artists working together. And Christmas is approaching, always a bad time for Vincent.

The day of the ear incident, a letter arrives from Theo announcing his engagement to Jo Bonger. It is not known if Vincent has read it before the incident. No one knows what happened. Gauguin’s account is not to be trusted, he was the only person there, and fled to Paris the next day.

Several breakdowns over the next month, and finally a petition to have him removed from the town, lead to him voluntarily entering the asylum as St-Remy where, between further attacks (often at moments in Theo’s life – his marriage, Jo’s pregnancy, the birth – that threaten access to Theo, and his money) he continues to produce fine paintings, several masterpieces.

I spent the morning walking around the Auvers, a bruise in my heart at where I will end up, meeting people in the streets and lanes – ‘have you found everything?’, smiles. A pretty place, with the poorest cottages that he painted long gone, ‘many villas and various modern bourgeois houses,’ ‘very radiant and sunny and covered in flowers’, lovely greenery in abundance and well kept.’ Daubigny, Pissarro, Cézanne, even Rousseau painted here. I had seen the previous day in Paris paintings Pissarro and Cézanne had done here, their green resemblance.

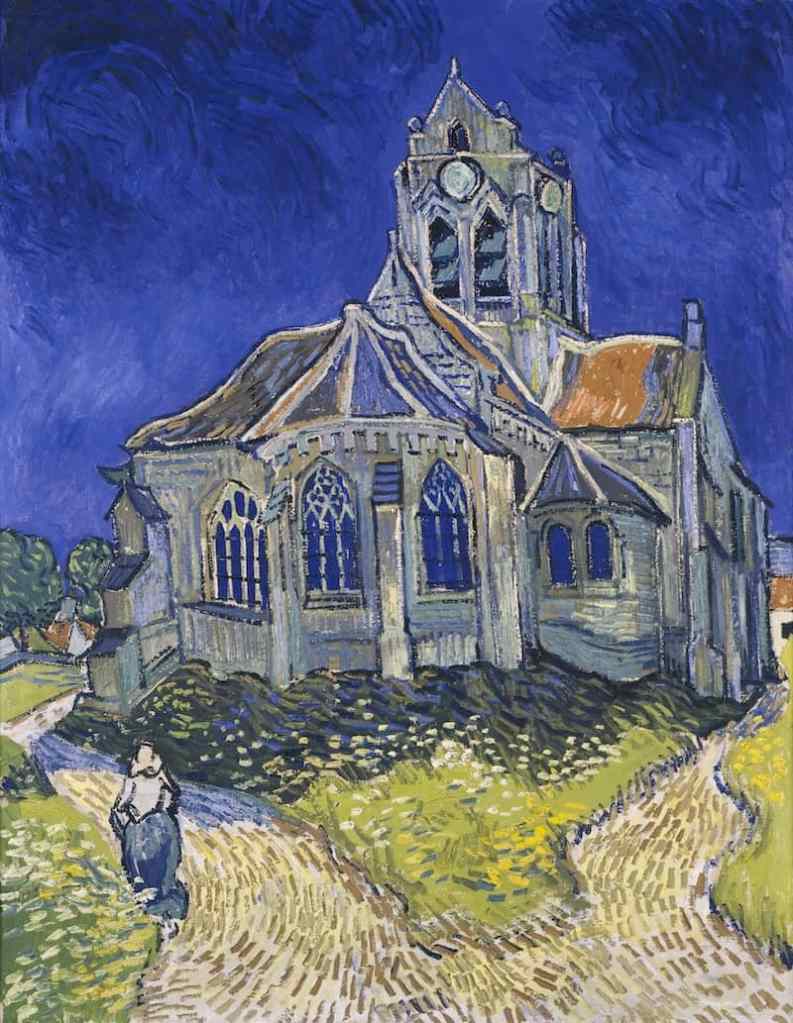

It’s a curiosity that wherever he painted, the locations are marked and copies put up, when there is such a disjunction between the motif and the painting – neither tells one much about the other, except in relation to his biography: the places look insipid, the pictures exotic. A Monet gives one a sense of what it must have been like to have been in that place at that moment. Cézanne sets up a mutual vibration between motif and painting, the intensity of his looking and the fastidiousness of his putting-on of paint making each uniquely important: the experiencing of one is amplified by the experiencing of the other. Picasso makes the subject look like the work. (Gertrude Stein, ‘I don’t look like that!’ Picasso, ‘you will’.) But Vincent. He had to paint ‘from life’ (he fought with Gauguin over this). But between the eye and the hand was not just a temperament but colour theory and facture theory. One is aware that he is consciously making a picture. His painting of Auvers church, for example: a grey, staid building, ‘appears purplish against a sky of deep and simple blue of pure cobalt, the stained glass windows look like ultramarine blotches, the roof is violet and in part red. In front a little flowery greenery and some sunny pink sand,’ he writes to his sister. He is describing not the church but the painting. So often the notion of his ‘madness’ is because his descriptions are taken to be of the place; they are of the painting. All sorts of theories can be (and have been) ascribed – the wonky lines of the building referring to the instability of the Church, the diverging paths and the woman on one of two paths, and one not taken in his life …. What really matters is that he has looked at a dull, grey church, and painted a picture that is colourful, vivacious and alive.

I realise that standing in the place is about identification. I imagine him standing here, still, summoning up the image in the Japanese way of hard looking, then painting quickly.

As I imagine him walking this road in his workman boots. And walking so many other roads, Ramsgate to Welwyn to see his sister, through the night from Roosendaal to the Zundert graveyard, across northern France from the Borinage to Jules Breton’s house, not daring to knock on the door, turning round and walking the fifty miles back. All the miles I cycled, through places completely changed.

Instead of, like Anselm Kiefer (born a month before me), visiting all the sites in one summer, painting 200 pictures, absorbing him and his work into his art body, and moving on, I made him a hero, the first of my heroes, Vincent, Dylan, Miller, Cohen, Rimbaud ….

All those boots, painted so often. Occasionally two left boots – when he was in conflict with Theo …? More freighting of images with meanings! He was not, as he says to Aurier, a symbolist.

I pass Auberge Ravoux, where he lived and died. I glimpse the skylight and shiver. Its facade changed many times over the years; now it has been painted as a copy of how it was in 1890 (there is a photograph of it then), including distressed signage. Is this recovered authenticity, or cultural tourism set-building? It is no longer a village inn, but a restaurant for fine dining. In Arles, the café terrace he depicted at night, and the hospital where he was admitted, have both been decorated, not in the colours they were, but in the colours he painted them. I imagine the Yellow House rebuilt and decorated, not as it was but as he depicted it. I imagine virtual reality stagings in which one can be in his pictures, as Kurosawa puts Scorsese in Dreams ….

I realise, over coffee, before I visit Auberge Ravoux, that I don’t want him to have cut off his ear, that, as one theory has it, it was Gauguin, whirling one of his duelling swords ineptly during one of their arguments. Would a man with no history of self-harm commit such a violet act? Would a bearded man have a sharpened open razor to hand …? And that I don’t want him to have shot himself, but, as another theory has it, happening in horseplay that got out of hand with well-connected Paris youths, on holiday, who alternately befriended him and played tricks on him, youths who were quickly whisked back to Paris. Why didn’t Vincent say? Because he always blames himself, believes that others have a greater claim on life than him, that everything happens for a reason. He often talked of death, welcomed it as the way out of an impossible situation (his brother now with a wife and child. And the child was a Vincent, to take the name on, as he had from the gravestone in Zundert graveyard …) But said that suicide made the suicide’s friends into murderers. He had written, ‘I would not seek death, but I would not try to evade it if it happened’. His death here, although painful, was peaceful, with Theo present.

And yet Vincent was becoming known, his pictures exhibited, written about, his first sale at a decent price. The article by Aurier, especially, published while Vincent was in St-Remy. While thanking Aurier for his praise, he was uneasy. Partly because he felt overpraised. But also because Aurier depicted him as a Symbolist, which he resisted. As all critics, Aurier had an agenda, in his case the promotion of Symbolism, and was recruiting Vincent and his work to the cause. For the first time Vincent was being written about, and therefore, misunderstood. And, as he wrote to Theo, ‘I foresee that praise must have its other side’. This was a world the unworldly Vincent was unprepared for, the problem of being known. It was alien to him as an artist. He wrote to Theo, ‘please ask M Aurier not to write any more articles about my painting, tell him earnestly that first he is wrong about me, then that really I feel too damaged by grief to be able to face up to publicity. Making paintings distracts me – but if I hear talk of them, it pains me more than he knows.’ That sense, always, of not being understood. Painting was hard. Being an artist was harder. In fact impossible.

Hence his attraction to secret artists, those whose essence of life is in making art, but who are unable to share it. The bedsitter minstrels. The kitchen table painters. The writers who write, perfect, then put in a drawer, positively hide their work from others’ eyes. For they know that they too will not be understood. That the understanding they gained from making their work cannot be shared, and that letting the world in will simply amplify that misunderstanding. (With sometimes an egotistical hope that post mortem their work will be discovered, with them free from the pain that will come from the lack of understanding.)

He left St-Remy feeling a failure, no longer heading out, being slowly reeled in, back to the North. So much of the energy of the radioactive meteorite that had left Holland had gone into his paintings. From Auvers he wrote to Theo, ‘I do not say my work is good, but it’s the least bad I can do,’ and still hopes that he can paint saleable work, to repay Theo. At Auvers he produces a body of work that most painters would welcome as theirs, but nothing great. The spring in Vincent has broken, and Theo’s family is a constant reminder of the drain he is. He says that to produce a child is more important than to produce art. He just wishes he had been able to, that art is a poor substitute.

Auberge Ravoux is a smart restaurant, with a museum upstairs. I watch the film, as several Japanese weep. I climb the narrow stairs to Vincent’s room. Every day, returning exhausted, up at five, bed by nine, the room under the eaves, facing west, stifling in the July heat. Stumbling up, hiding his wound, too embarrassed to make a fuss. Theo is called, arrives the next day, Vincent dies, in pain but peacefully. Here, in this attic, is the end of one story.

Bernard, Tanguy, Lucien Pissarro are summoned from Paris. Jo’s brother, Andries Bonger is there. And Dr Gachet and family. Theo is the only mourner from the Van Gogh side. The coffin is surrounded by Vincent’s paintings. He is buried in a grave on a fifteen-year lease. The wake is at Ravoux’s. Theo collapses, goes into hospital and, overtaken by syphilis, dies six months after Vincent.

At the edge of the village, in the cemetery, the beginning of a new story is illustrated:

Vincent and Theo, side by side, with identical gravestones, and covered with flower-strewn ivy like a counterpane.

After Theo’s death, his widow, Jo Bonger, while raising their son, takes on the task of making Vincent’s story and work public. She collates and translates his letters, and has them published in Dutch, French and English. She curates his work with a skill and in a way hardly known then. She contacts and forms relationships with galleries and dealers, to get Vincent’s painting into exhibitions, into the public eye, and into the international market. She takes great pains to place his paintings with the great galleries of the world. And there are enough paintings left in her ownership to found the Van Gogh museum in Amsterdam, the most-visited single-artist gallery in the world.

In 1905, when the grave lease runs out, she transfers Theo’s remains from Utrecht, and buys two perpetual plots, adjacent, the brothers together, ‘Vincent’ their joint enterprise.