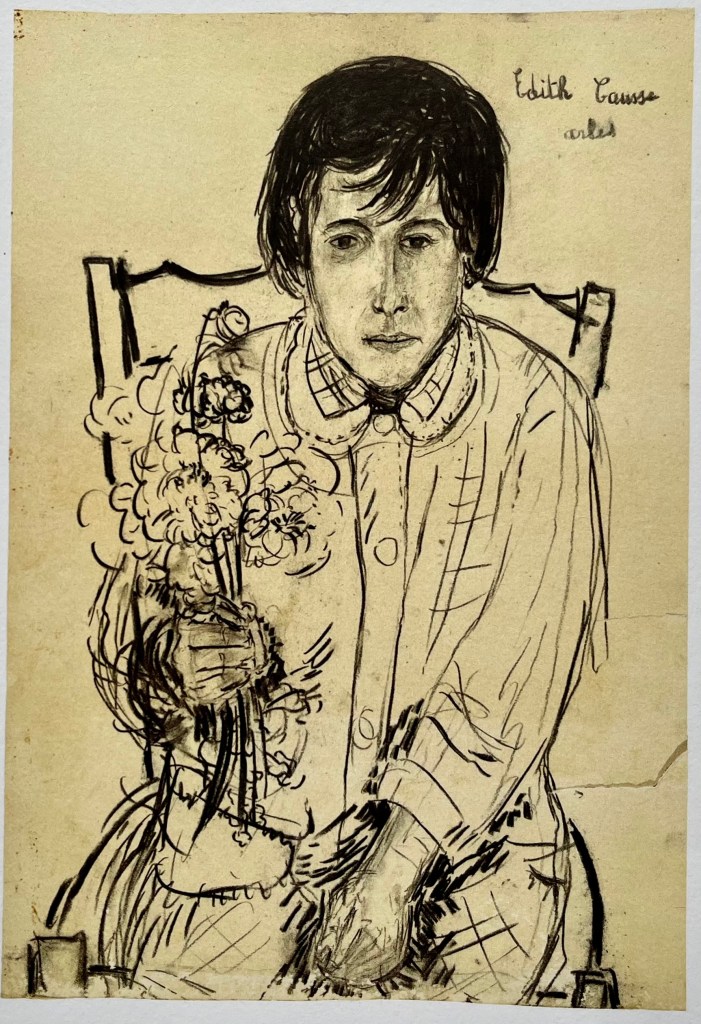

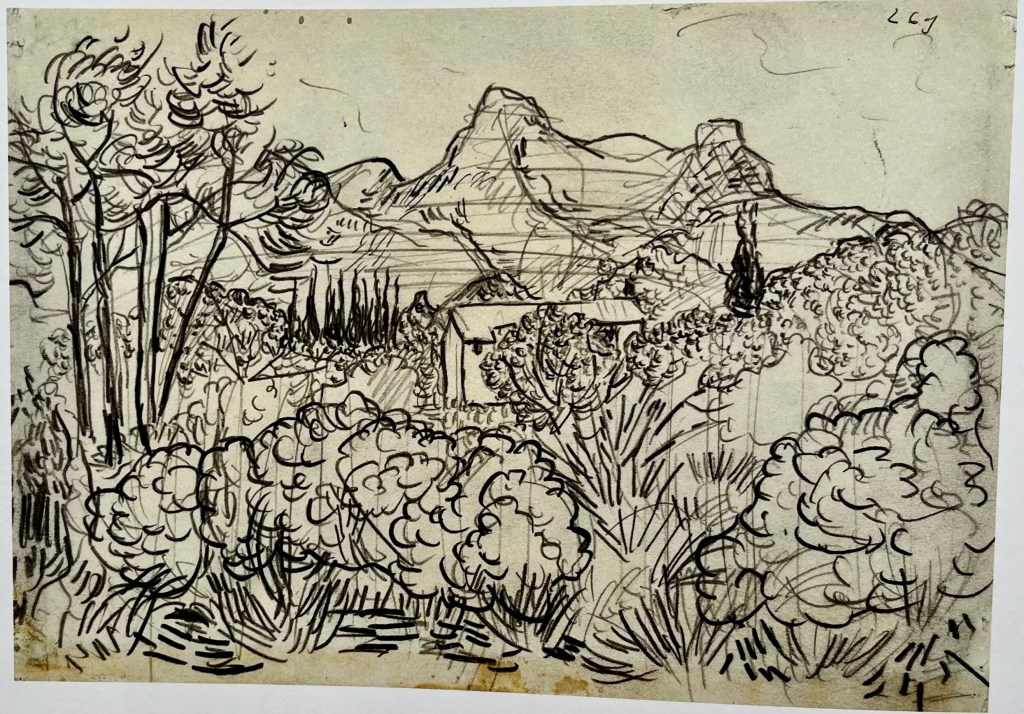

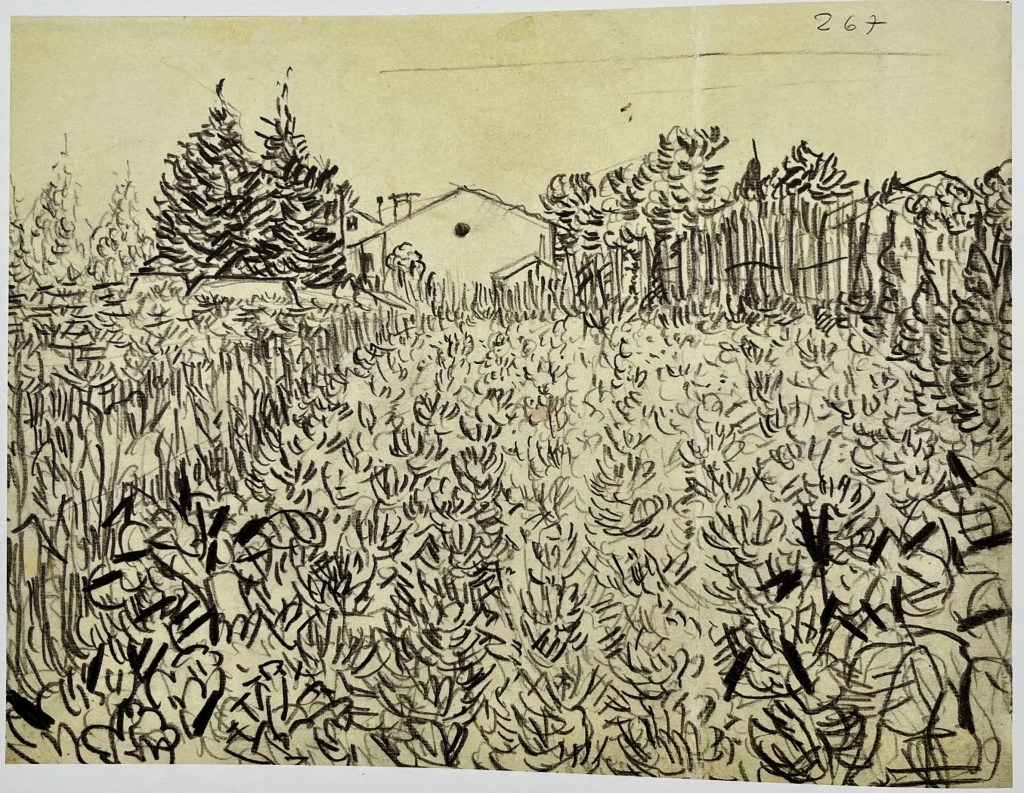

In 1963 school student Anselm Kiefer received a grant to travel ‘In the footsteps of Van Gogh’, through the Netherlands, Belgium, Auvers and Paris, to Arles. With remarkable self-confidence the eighteen-year-old left his village near the Rhine for the first time, hitchhiked across countries occupied by Germany less than twenty years before, sleeping in barns and working on farms, and returned with a diary and over 300 drawings, which won him the John Walter Prize, and was widely published. There is a piece of film of the presentation, in which the eighteen-year-old Kiefer is the image of quiet containment and self-possession, there and not there.

And his sketches are assured and vigorous for one not yet even an art student:

As with my first trip abroad, recounted in ‘Vincent and I : A Lifelong Passion’, such journeys are at their best voyages in which the unexpected is revealed in both the outer world and inside the self, and a new way of being, and proceeding, is shown. For me it had been out of the full light of the academic mainstream, into the half light of ‘the outsider’, and the possibility of a different way of creativity.

For Anselm it was different. In 2025 – by which time Kiefer was acknowledged as one of the great artists of his generation – on the occasion of a joint exhibition with Van Gogh to mark his 80th birthday, he writes: ‘Contrary to what one might expect of a teenager, I was not overly interested in the emotional aspect of Van Gogh’s work, or his unhappy life. What impressed me was the rational structure, the confident construction of his paintings, in a life that was increasingly slipping out of control. Perhaps I felt, even then, that an artist’s work and his life were separate.’

He then ponders ‘talent’, and Vincent’s manifest lack of it. ‘So, is there something higher than talent? Why did Van Gogh give up on his ambition of becoming a pastor? Because he did not have the talent for it. Why did he not give up on his ambition of becoming a painter? Because one can be a painter even without talent.’

He goes on, ‘With Van Gogh, his paintings are a feast despite everything. One believes in him. He defies all adversity; he does the impossible; he does not give up. His path – from what he set out to achieve to what he did achieve – is visible in almost all of his paintings. Every single one of his brushstrokes is an eruption, a manifestation of defiance. Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus comes to mind.

‘Although I did not recognise it when I was travelling in Van Gogh’s footsteps, this defiant determination not only to attempt the impossible but to force it was what attracted me to the artist and continues to do so today.’

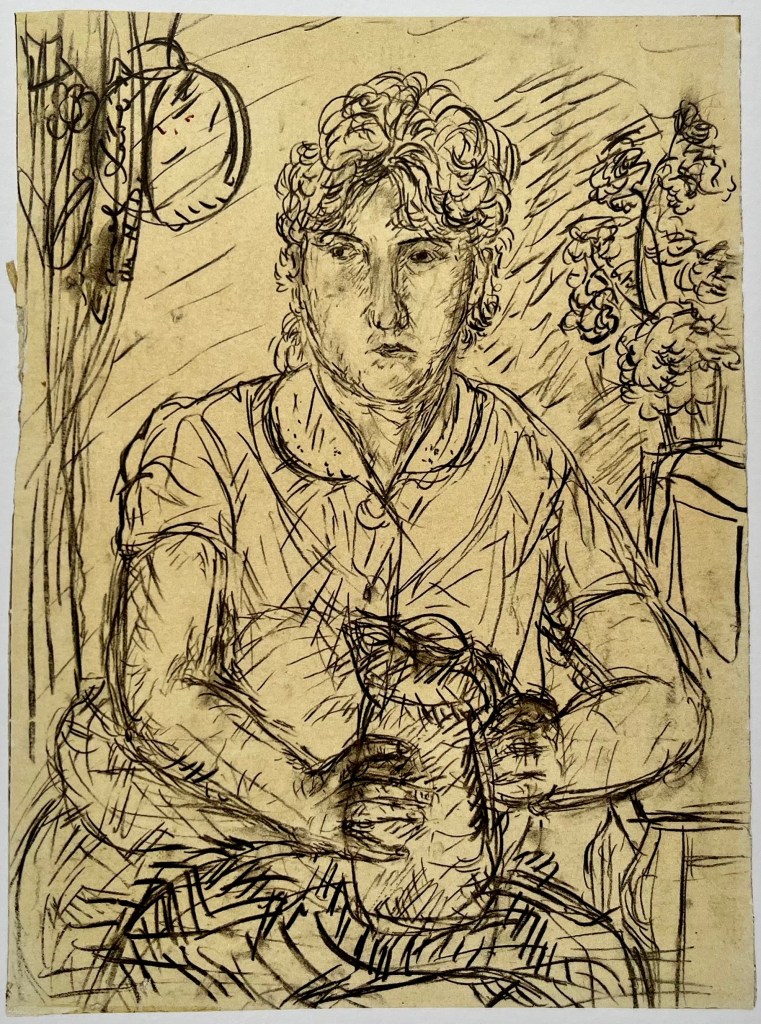

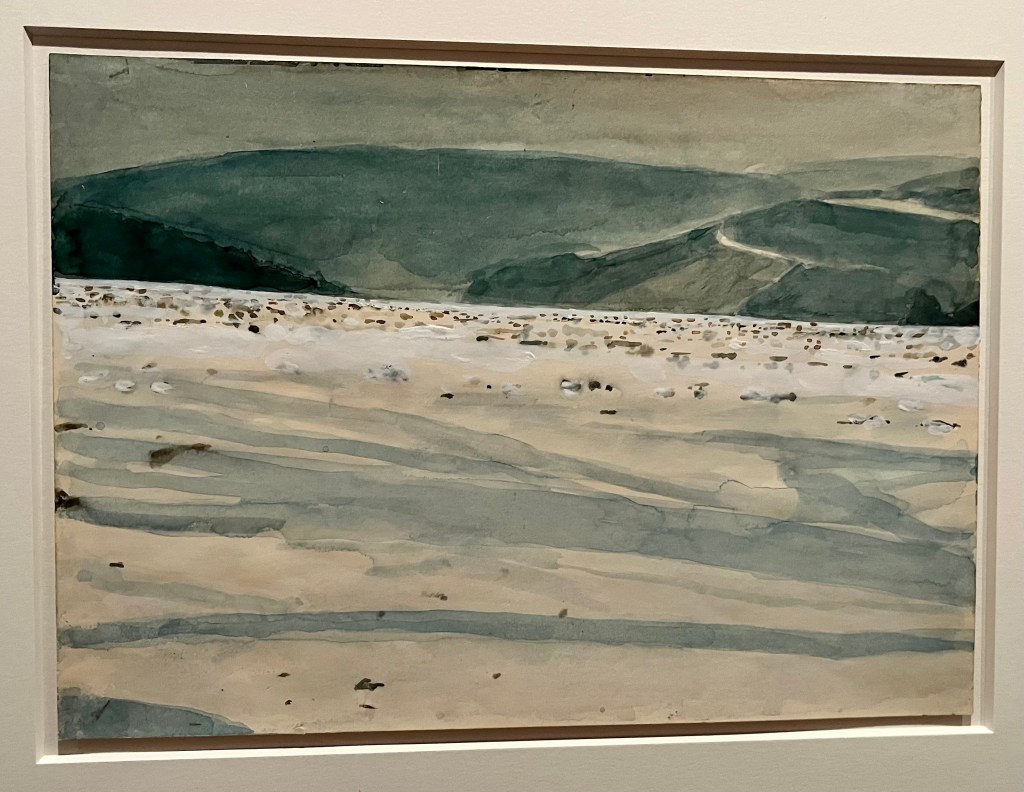

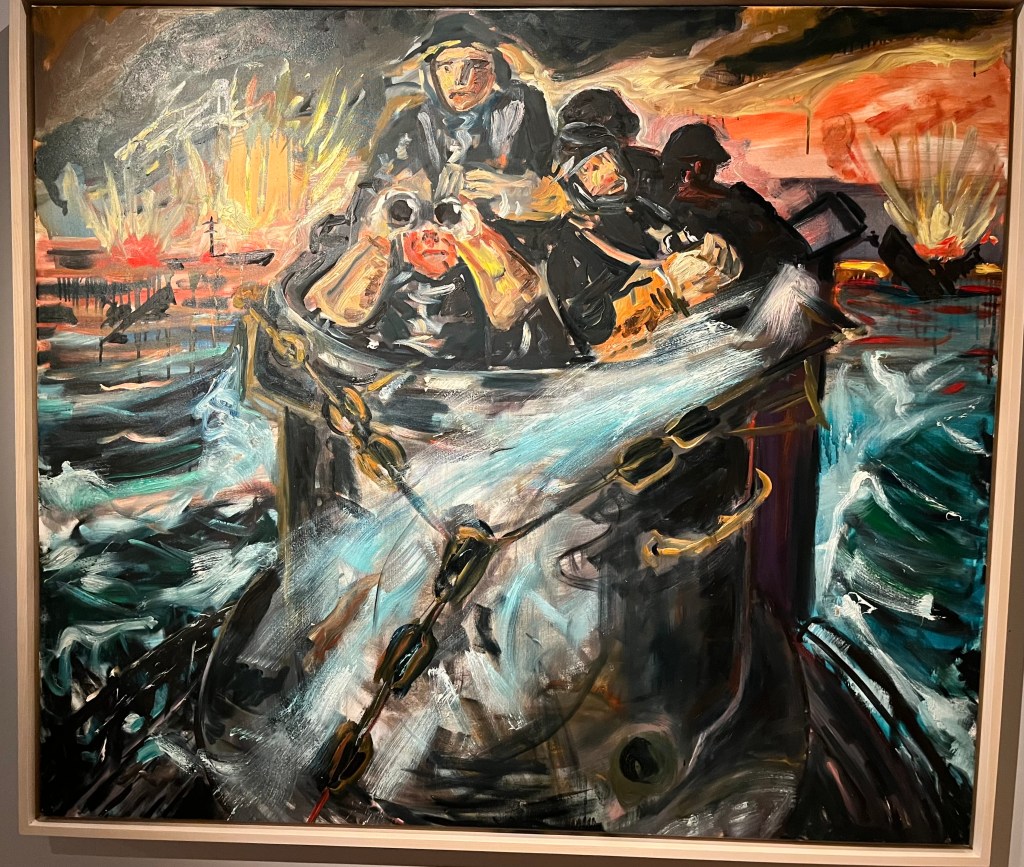

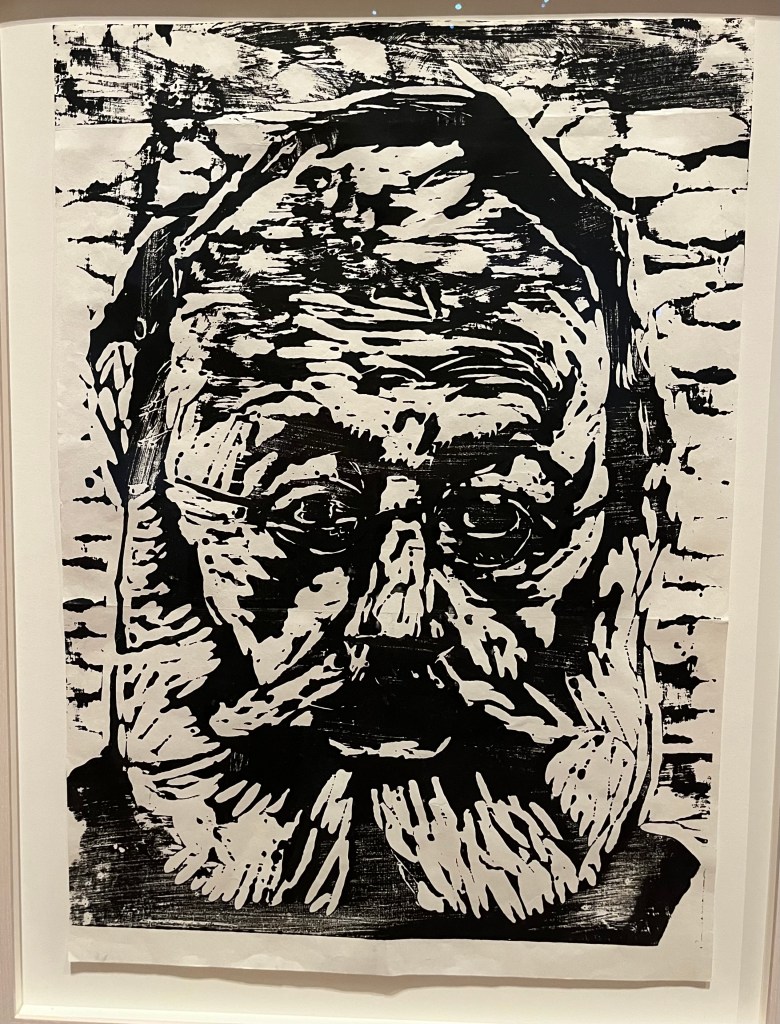

He writes of his own lack of talent, which seems at odds with his work, which from the earliest (these from his twenties), whether watercolour, oils or woodcut, is accomplished and striking:

But this, as he says, is the outcome of ‘endless struggle and the destruction of images. I once said that only the iconoclast is a true artist, turning my incompetence into a virtue.’ What he sees and identifies with in Van Gogh is his perpetual working at the limit of possibility, the edge of failure, his paint marks (so many paint marks!) resisting the tip over (like Hokusai’s wave) into oblivion. No wonder Vincent’s constant fury, and the many evenings he was too weary even to write to Theo, and could only reach for the bottle.

Using ‘Wheatfield with Partridge’ as an example, Kiefer praises Vincent’s framing, in horizontal strips, and the way he builds the landscape, ‘like a bricklayer, brush stroke by brush stroke,’ constructing it ‘with workman-like clarity. And yet we are moved, overwhelmed even. Despite the simplicity of the composition, the painting speaks to us, and we feel that our own uncertain approach to the world has been laid bare.’

It is a composition and method Kiefer uses often, in framing and construction, but on a vastly greater scale. This work, ‘Field of the Cloth of Gold’, is 25 feet long. It is made of acrylic, oil, shellac, poured and painted and trowelled on, to build a surface inches deep. The surface isn’t paint marks but straw embedded in the surface. And the gold isn’t yellow brushstrokes, but gold leaf.

Kiefer was next in Arles in 1969. Now an art student, he performed one of his Occupations in the Alyscamps, the Roman necropolis where Vincent had painted with Gauguin. In this project, he had himself photographed in various locations, often wearing his father’s Wehrmacht uniform, performing the sieg heil salute, illegal in Germany. He was drawing attention to the elision of the Nazi period from German history, and the silence over the number of Nazi sympathisers still running German industry and institutions.

In that period of student radicalism, while the Red Army Faction adopted violence and terrorism, and the Greens sought political legitimacy, Kiefer aimed to reclaim German cultural traditions from the Nazis. Including the cult of the forest and the defeat of the Romans in the Teutoburg forest, the Nibelungen tales, Wagner’s operas, and the Romantic paintings of Casper David Friedrich.

Indeed, although Kiefer is clearly both successful and cosmopolitan, his overt cultural references stop with an event on the day of his birth, 8 March, 1945, when an allied bomb blew up the house next door, depositing the neighbours’ Singer sewing machine onto a pile of rubble in the middle of the street. Incongruous juxtapositions and heaps of waste – having grown up amid bomb damage – are integral to his practise. And his references are backward, to German history, Jewish mysticism, and alchemy. And yet full of relevance today.

Alchemy connects with his interest in lead, the base metal from which gold is made in the alchemical process. Also he values its malleability – he builds aeroplanes and submarines out of lead. Again the incongruity of making craft too heavy to fly or float.

And his enormous lead books, which, in my first encounter with his work, stimulated me to write:

“The lead library

books too heavy to lift

and you must wear gloves

when you turn the pages

to protect yourself

from contamination.”

And quote Kiefer: ‘It’s the condition of the artist to stand outside. if he doesn’t stand outside, he’s lost. Art doesn’t belong to a present structure of society, it belongs to another level, and from this standpoint all is moving around, and this relates to the physical recognition that there is no fixed point.’

He quotes with approval Heraclitus’ panta rhei, ‘everything flows’. And was delighted to discover, when he bought the lead roof tiles from Cologne cathedral, that they were wider and thicker at the bottom – in the centuries the lead had slowly flowed, drawn by gravity.

He enjoys the ease with which lead melts and flows – he pours molten lead onto pictures, onto sand hills that it flows down, accepting the serendipitous outcomes.

His interest in molten lead took me back to my childhood. We lived in a world of lead soldiers, armies of them that we accumulated with weekly pocket money spends. In the inevitable fierce battles (we were children of the war, although growing up after it, and all our interactions were of combat, whether cowboys and Indians, Japanese and commandoes, or Robin Hood against the Sheriff of Nottingham) figures became damaged beyond use. We found out – where from? Maybe the workmen on the clearance and building sites we hung around, where there was always a fire burning – that lead melted easily. We learned about moulds, and pressed the soldier we wanted to copy into builders’ sand and optimistically poured in the molten lead. Of course the sand was too coarse, and didn’t keep a decent shape, and was too wet, so the lead spat (we all had at least one pock mark on our faces from the spitting lead). So we ended up with a shapeless mass. We lowered our expectations and produced fishing weights, and lead to pack into our Dinky cars to speed them in our downhill races.

The child in me delighted in Kiefer making art with molten lead, and sticking straw onto pictures and setting it on fire.

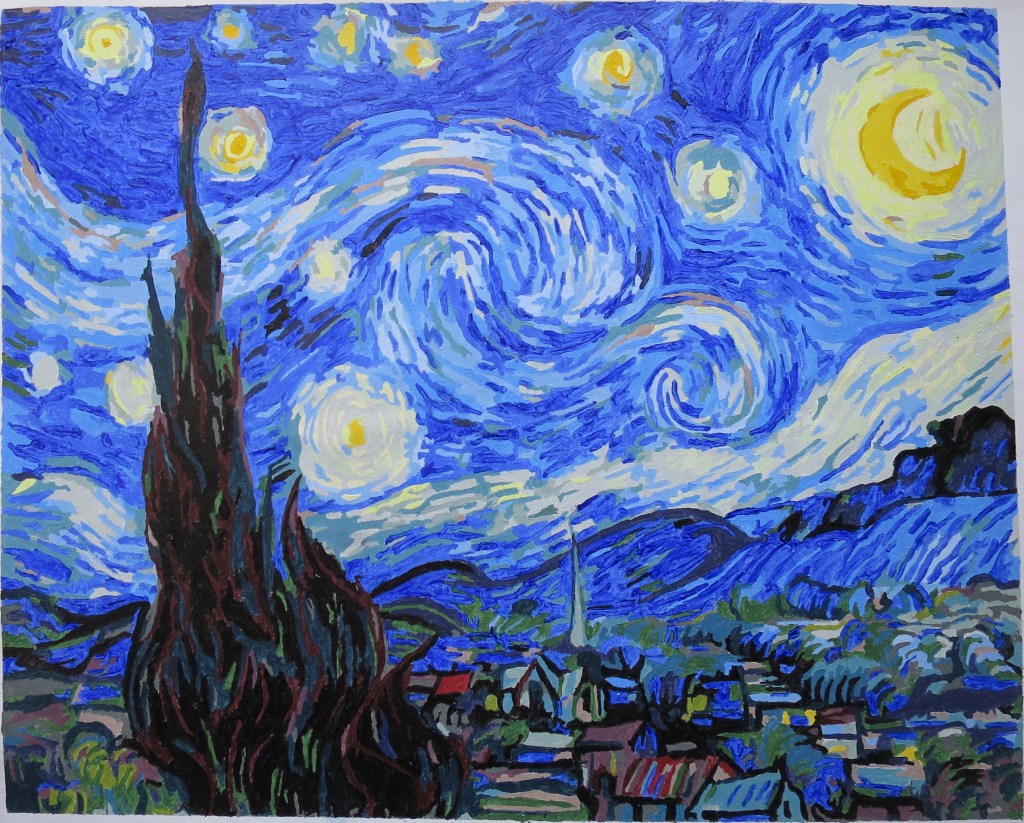

Kiefer also looks at Van Gogh’s Starry Night, ‘constructed from brushstrokes that form spirals. Then there is the strange dragon, which recalls The Book of Revelation; and the stars, each of which creates its own spiral. And finally the moon, which is illuminated even inside its crescent.’ It reminds him of string theory, ‘different multi-dimensional spaces arising out of each other, entangling and disentangling.’ The earthbound elements, the dimly-lit village, the cypress and the church spire, neither ground nor penetrate ‘the monstrous billowing plasma’, and ‘the astral roar [that] is bound to consume and extinguish them.’ ‘It offers no insight, no outlook,’ reduces Kiefer to Moses Herzog’s only hope, to “hitch one’s agony to a star.” ‘I tried this during a very difficult time,’ Kiefer continues, ‘and I managed to gain control over my life again.’ Which Vincent, by this time, could not do.

Kiefer attempted his own Starry Night, but in spite of its size, for me it has neither the grandeur nor the energy of Van Gogh’s. As if even an artist as fine as Kiefer was overwhelmed by the comparison.

While in Arles, in the September before Gauguin arrived, Vincent engaged with the stars in a less anguished way. He surrounds his portrait of Eugene Boch, ‘The Poet’, with stars like flowers.

And his Starry Night over the Rhone is a Romantic evocation of earth and the heavens in harmony. He painted it ‘after a walk along the shore. It was not cheerful, it was not sad. It was beautiful.’ Beauty a word he uses rarely. And this: ‘I have an immense need for (should I use the word?) religion; and then i go out into the night and paint the stars, and I always dream of such a picture with a group of lively friendly figures.’ It was important that he painted from life, as part of his battle with Bernard against painting from imagination. And although tales of him having candles around the brim of his hat are apocryphal, he did paint it under a lamp standard, then gas, now electric, that is still there. (Although, for all his fidelity to the motif, he painted the familiar constellation the Plough, which is never in that quarter of the Arles sky.) Again the stars are painted like flowers. And Kiefer notes the alchemist Robert Fludd’s belief that every flower on earth has its corresponding star in the sky.

Writing to Theo about life and death, ‘I declare I don’t know anything about it. But the sight of the stars always makes me dream, in as simple a way as the black spots on the map, representing towns and villages make me dream. Why, I say to myself, should the spots of light in the firmament be less accessible to us than the black spots on the map of France? Just as we take a train to go to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to go to a star. What’s certain is that while alive, we cannot go to a star, any more than once dead we’d be able to take the train. So it seems to me not impossible that cholera, the stone, consumption, cancer are celestial means of locomotion, just as steam boats, omnibuses and the railway are terrestrial ones. To die peacefully of old age would be to go there on foot.‘ (My emphasis.)

When writing of Wheatfield with Crows, Kiefer references Bataille’s The Blue of Noon, a figure ‘overlooking a cemetery, whose graves are marked by the flickering light of candles. The vertiginous view becomes a vision of the night sky lit by starlike graves, “this empty space at our feet was no less infinite than a starry sky over our heads … the lacerating fall into the void of the sky.”‘

Which reminded me of an incident in Diggers and Dreamers, in which Kris, having drunk too much, angry, and driving too fast at night, runs out of road. “I swear, hit the brakes, skid, curse myself, wait as the car slides. The car stops. With its nose over a precipice. I stare into the abyss. But an abyss full of stars. Am I upside down? Are they stars reflecting in a lake? And then I realise they are the lights of St-Leon. Each light is a star, comforting in its mirroring of the firmament. I reverse, drive on, a bubble of wellbeing growing in me.”

Not knowing why, Kris builds a circle of stone, then prepares to roof it with a geodesic dome. “I’ve finished making the struts for the dome. Tomorrow I’ll start fitting them.

“It is dark. I go out and step inside the wall of stone. I close the door, lie down. I am lying in a crater in the desert, where a meteorite fell millennia ago, a black stone. The sky is a velvet pall pricked by ten thousand pinpricks through which is visible the empyreal light. The points of light are suns, nuclear fusion furnaces millions of degrees hot, isolated in the absolute zero of space, moving steadily apart. The stars group into galaxies, the galaxies into clusters, the clusters into clusters of clusters, all relating to each other in a curved space-time continuum predictable within a chosen frame of reference. The stars resolve into heroic constellations that tell true stories, into zodiacal constellations which by their subtle powers affect our lives … The sky, with stars lambent and lustrous, sharp and brilliant, is wonderful tonight.”

Fitting the ribs of the dome, with the last one in place, from being a mass of heavy wooden struts that Kris is supporting with props and scaffolding, it suddenly becomes, “weightless, self-supporting. Rather than a structure to enclose or exclude, it is an aspect of space. It floats, an idea.

“I stood inside it, quoted ‘Every human being stands beneath his own dome of heaven,’ the title of a Kiefer painting.

“I walked around it. I looked at it from every window in the house. I drove up to the rim to see it in the setting of the hamlet. It is perfect. Aesthetically, geometrically, geomantically perfect. I can feel its influence singing along ley lines to the seven great centres of the earth. At last I’ve done something.

“When it got dark I went inside the tower and lay down and stared up. The pattern of ribs was black against the starry sky.

“At first I saw triangles. Small triangles; large triangles made up of small triangles – and suddenly the Pythagorean “holy tetractys”, the ten dot triangle or pyramid that represents position, extension, form, the elements, number, the triple Goddess … The triangles merged into diamonds, separated and re-formed into other triangles, other diamonds; and then hexagons – hexagons most of all, dissolving and resolving, overlapping and ever changing hexagons. Except at the top of the dome; there, where the Great Triangles (which are Great Circles) meet, there, uniquely, is a pentagon. A space that connects. An absence that creates presence. All around it is change, flow of energy: there, is stillness. My eye wanders excitedly over the pattern of triangles, as it would over an Islamic mosaic, or the face of a sunflower; and then returns to rest on the still eye of the pentagon.

“I look at the stars, no longer free, through a mesh now, a net thrown over them …”

A final reference to Vincent, Anselm and the stars. Untitled, 1974 depicts a red painter’s palette flying through the black of space, among stars, towards a bright light. Kiefer used the winged palette to represent the artist, his aspiration and effort, flying ever higher. And therefore, as with Icarus, as he approaches the sun, ever more at risk. And it is impossible not to see Vincent as Icarus, with his obsession with the sun, and the way the sun of the south both released his greatest creativity, and precipitated his mental collapse. And identify Kiefer, in spite of his need at times to “hitch his agony to a star”, still productive at 80, with the persistent craftsman Daedalus.

Kiefer writes of one of Vincent’s last paintings, Wheatfield with Crows, ‘What we have in front of us here is not really a billowing golden wheatfield. These thickly applied brushstrokes have nothing in common with the delicate structure of a blade of wheat. It is not the visualisation of something we know.’ ‘While we know that Van Gogh painted the work in front of the landscape, what is shown is no more than a starting point. He builds a world, but it is a struggle between this world and the self-secluding earth. Every energetic brushstroke is an attempt to capture it; he tries to support himself on it – he is holding onto a straw. He tries to rebuild it with these forcefully applied brushstrokes. And yet, what a failure; earth defies him.’

The sky becomes the universe, and devours the painter, dissolving into infinity. ‘That said, it is not quite clear whether the all-dissolving brushstrokes capture the infinitely big or the infinitely small, the cosmos or the microcosm. It brings to mind the Merkabah homilies and Jewish mysticism, in which the initiate roams the seven heavenly palaces. In this mystical journey, ascent into the cosmos coincides with descent into one’s inner self.’

And he draws attention to the reverse perspective, in which ‘the vanishing point, which should be on the horizon line, is flipped to the lower edge. The universe has been upended.’ The paths are an arrowhead, its point penetrating the artist.

Kiefer has painted his own Landscape with Crows, a more successful ‘take’ on a Van Gogh picture.

He writes that in Van Gogh’s pictures, ‘The earth is the secret which the artist in his struggle does not so much resolve as guard.’ ‘What we have in front of us is a well-ordered, accessible structure, which at the same time contains an inaccessible secret. This is even more evident in the paintings Van Gogh painted just before his death. Having reached the finishing line, having become a master, having made up for his lack of talent, at a time when he could have continued in full command of his options – then is when he gave up.

‘Did Van Gogh give up? Or is it as in Hölderlin’s poem, To The Fates

‘Give me just one summer, you Mighty Ones!

‘And an autumn to perfect my song,

…

‘The soul denied its god-given right in life

‘Will not find rest down in Orcus either.

‘But when I have accomplished my great task,

‘Perfected the poem on which my heart is set,

‘Then be welcome, silence of the shadow world.’

Whether Vincent shot himself, or was shot, he did not resist the ‘silence of the shadow world’ when it came.

Notes

Two 2025 exhibitions were key to this piece: ‘Anselm Kiefer, Where have all the Flowers gone,’ at the Van Gogh and Stedelijck Museums in Amsterdam. And ‘Anselm Kiefer: ‘Early Works’, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

‘Kiefer / Van Gogh’ at the Royal Academy, London, 28 June to 26 October, 2025, will also consider the connection between the two artists.

Quotations are from Kiefer’s essay, ‘In the Footsteps of Van Gogh’ in ‘Anselm Kiefer, Where have all the flowers gone’, the catalogue for the Amsterdam exhibition.

Two films are important:

‘Over the Cities Grass will Grow’, 2011, directed by Sophie Fiennes, surveys the astonishing Gezamtkunstwerk that Kiefer created at Barjac, not far from Arles, with towers, streets, pavilions, tunnels, that both display his art, and are his art. I haven’t touched on it here, but it is a place I hope to visit, one day.

‘Anselm’, 2023, directed by Wim Wenders. (Also born in 1945, and one of my favourite film directors.) Filmed in 3D, but rarely shown in that format; I’ve only seen it in 2D. Even in 2D, it is a spacious and immersive exploration of the artist and his work that carefully connects the two.