I walk down towards Pigalle. Cheap, grim hotels. Graffiti, ‘CHA CHA I HEART YOU’, many times, obsessively, I remember someone we knew in London, fixated on a call girl associated with a politician, fired shots through her door, blew up a scandal. Walking in front of me an oriental woman in black wide-brimmed hat, leopardskin coat, black skirt and stockings, six-inch heels, going on shift? A massage parlour and a sex shop. And I’m at Bvd de Clichy.

Bvd de Clichy is on the line of the Farmers’ General wall. This wasn’t a defensive wall, but built by tax farmers to collect the octroi tax on goods coming into the city. They collected it on behalf of the city, took their cut, and became fabulously wealthy. It was 24km long, 3m high, with 62 gates, built 1784–91, and much resented by Parisians – “le mur murant Paris rend Paris murmurant”, and “to increase their cash, and limit our horizon/ the farmers judge it necessary to put Paris in a prison.” – as walling them in. It stimulated leisure industries in Montmartre, outside the wall, where food and alcohol were cheaper and activities less regulated. Parisians streamed out for pleasure. Workers, as described in Zola’s L’Assommoir, streamed in to work. “You could tell the locksmiths by their blue overalls, masons by their white jackets, painters by their coats with long smocks underneath.” (p25.) Then they were building Paris. Now the shop assistants and hairdressers, security guards and maintenance men who fill the early-morning metro trains from the banlieus are servicing it. The wall was demolished after 1860, when the boundary of Paris was extended out to where the Thiers wall would be built. The road alongside it was widened to this Boulevard.

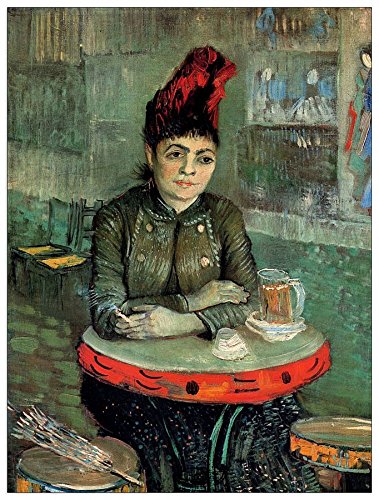

So many names associated with Bvd de Clichy! Manet painted ‘Chez le Père Lathuille’, and Degas ‘The Absinthe Drinker’ in bars here. The Moulin Rouge is here. Studio Cormon was here, where Van Gogh met Toulouse-Lautrec, Anquetin and Bernard. And Le Tambourin, where Van Gogh exhibited his paintings, had a brief liaison with la patronne Agostina Segatori, and painted her at one of the tambourine tables, with Japanese prints on the wall. Agostina had been an artist’s model, one of the Italian girls with tambourines who gathered at Pigalle to find work. Cirque Medrano, where Suzanne Valadon performed, and Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir and Degas painted. Le Chat Noir night club, where Satie played. Picasso lived and worked here before and after his time in Le Bateau-Lavoir. For thirty years it was the centre of the avant-garde. And later – André Breton lived here, and met Nadja here. Boris Vian shared a flat with Jacques Prévert.

Now taken over by the commercial sex industry, of trafficked girls run by immigrant gangsters, rough, violent and drug-fuelled. And on the ribbon of land between traffic lanes, alongside the unused electric-car charging points, the homeless, the addicted and the mentally ill. I flee across this world, cross from 18th arrondissement into the 9th. Into old Paris.

Just south of Pigalle, at 25 rue Victor Massé, was where Theo van Gogh was living when Vincent arrived unannounced in March, 1886. Exactly ten years earlier Vincent had been sacked by Uncle Cent from his post at Goupil’s in nearby rue Chaptal. It was perhaps to escape the unhappy association that he persuaded Theo to move up to rue Lépic. After he married Jo Bonger Theo returned, to cité Pigalle.

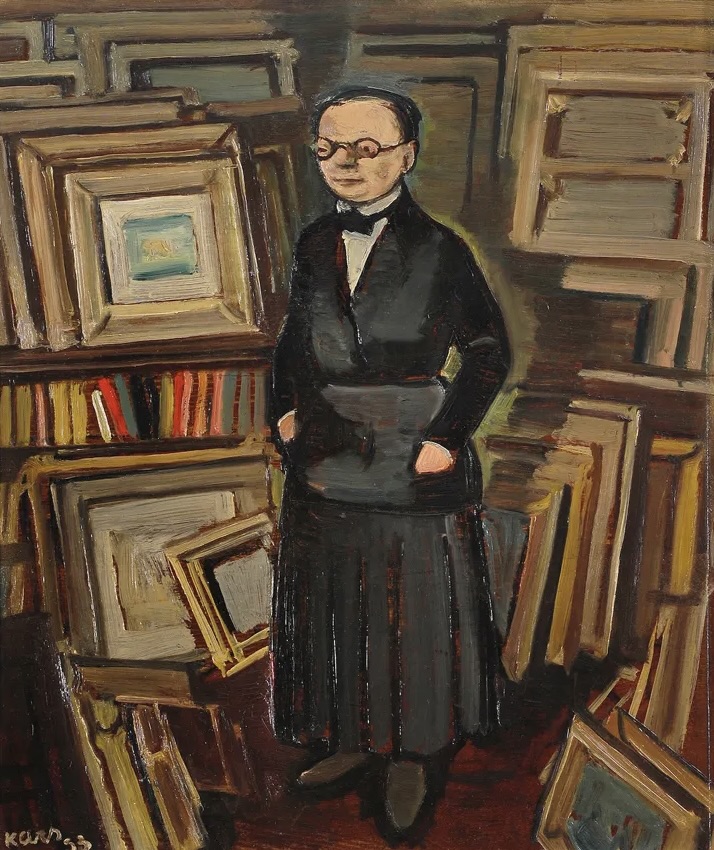

Berthe Weill opened her gallery at the same address in 1901. She had already bought from Matisse and Picasso (before he moved to Paris), their first gallery sales. She introduced the artists to Leo and Gertrude Stein, and persuaded them to buy their work. She gave many artists – Dufy, Derain, Vlaminck, Braque, Utrillo, Suzanne Valadon, Fauvists and Cubists – their first gallery sales, encouraging them until they moved to more commercial-minded galleries. Picasso moved to Kahnweiler in 1904 – ‘what would have become of us if Kahnweiler hadn’t had a business sense?’ Which Weill didn’t have. Picasso continued to support her, giving her pictures. She gave Modigliani his only Paris show, in 1917, and the tiny, bespectacled fifty-year-old was marched to the police station for refusing to cover his ‘obscene’ nudes. She was especially supportive of female artists. She never built up a collection, and was left penniless when antisemitism forced her to close her gallery in 1941. In 1946 dozens of artists donated works for sale, to raise money for her. She was largely forgotten after her death in 1951, until the last twenty years, when her memoirs have been republished, a biography written, and Picasso’s portrait of her designated a national treasure.

The Cotton Club opened at the same address in 1920. And Iannis Xenakis, architect, composer and musical theorist, lived next door for 30 years.

The artists’ materials shop of Père Tanguy was in nearby rue Claudel. It was a gathering place for the new artists of the 1880s. Van Gogh met Gauguin there, saw pictures by Cézanne, and painted three portraits of Tanguy, two much influenced by Japanese prints.

I walk down towards the church of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette on rue de Chateaudun. The slope up from there, marking the rise from the old bed of the Seine onto the limestone butte, “is recognised by the flâneur as he stands before the church and his soles remember: here is the spot where in former times the cheval de renfort – the spare horse – was harnessed to the omnibus that climbed the rue des Martyrs towards Montmartre.” (Walter Benjamin, Arcades Project, p 416.)

The slope up from rue de Chateaudun was developed from 1820s. It became known as New Athens, because of the cultural figures who congregated here: Chopin, Georges Sand, Delacroix, Victor Hugo, Henri Monnier, Gavarni, Alexandre Dumas.

It also became the Quarter of Kept Women, from mistresses kept in the highest style, like Apollonie Sabatier, to lesser courtesans, and women of the demi-monde making a precarious living in ‘society’, who took over the newly built houses around Notre-Dame-de-Lorette church on temporary leases, “while the plaster dried”. “Once in possession of the new quarter, from which their turbulence repelled the peaceable and well-behaved bourgeoisie, they never abandoned it. A joyous, careless, disorderly colony perpetuated itself in this fashion, paying its rent with the most regular irregularity.” As La Bédoullière, in Hazan (p144) romanticised. They became known as ‘Lorettes’, a name that was then applied more generally to women working across the broad range from prostitution to courtesan to established mistress. Originally the front of the church was to face Montmartre; the revised plan turned its back on the new development.

Apollonie Sabatier, ‘La Présidente’, lived on rue Frochot, near rue Victor-Massé. Born in 1822, illegitimate daughter of a Count, raised as the child of a soldier, she was successively a singer and artist’s model – posing for Clésinger’s sculpture, ‘Woman bitten by a Snake’, which scandalised the salon of 1847. It had been commissioned by the Belgian tycoon who kept her in the highest style until his death in 1867, when she became the mistress of Sir Richard Wallace, he of the fountains. A patron of the arts, she held a weekly salon, attended by the writers, painters and composers of the day, including Nerval, Flaubert, Maxime de Camp, Berlioz, Manet. Many of the poems in Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal were inspired by her – “You are more than an image I dream about and cherish, you are my superstition” he later wrote to her. He had sent them to her in a disguised hand. When she found out, she offered herself to him for one night.

In Flaubert’s Sentimental Education, his hero Frederic attends a much wilder event at rue Frochot, a costume ball presided over by Apollonie, where he acquires, “a thirst for women, for luxury, for everything life in Paris implies.” p133.

I enter place St-Georges. It is a circle 32.5m in diameter, its hub a columnar monument to the satirical illustrator, Gavarni. A driver stands by a limousine parked on double yellow lines, relaxed. A smartly dressed man, neat grey hair, walks briskly from a house, shakes the driver’s hand, walks around to the other side of the limo and climbs into the rear seat, without the driver opening the door for him. The car moves silently away. And leaves a space. Time stills. And my attention slowly circles the place widdershins:

To the trompe-l’oeil facade of the Theatre St Georges, hardly noticeable as trompe-l’oeil until I see that the shadows are not aligned to the sun, and that the ‘projecting’ dragon’s head is painted on the flat surface. Truffaut filmed Le Dernier Métro here in 1980.

To the house of Adolphe Thiers (he of the Thiers Wall), who led the government forces against the Commune. The communards burned it down. The government rebuilt it for him in 1873.

To the opulent mansion of La Païva, where she lived while her even more opulent mansion was being built on the Champs Élysees, with its silver bath with three taps: hot, cold, champagne. Described as so hard-bitten that “she is the one famous courtesan who appears to have no redeeming feature,” yet when she died, her husband couldn’t bear to bury her, and kept her body in embalming fluid in the attic. Much to his new wife’s surprise.

To the offices of the Paris Gas Board, where in 1937 Fulcanelli – who had decoded the alchemical messages carved into the stone of the gothic cathedrals – revealed to the physicist Helbronner that alchemists, without recourse to electricity or modern technologies, had discovered the geometrical arrangements of highly purified materials that would release atomic forces. For moral and religious reasons they had refrained from proceeding. Something which, he predicted, rationalist, ‘Enlightenment’ science would show no such restraint. As would be demonstrated in 1945. For whereas in science and technology the operator is outside, opaque, manipulating matter and energy, the alchemist is inside the process. A necessary step is the transmutation of the alchemist himself, his spiritual liberation, which enables him to be part of the geometrical arrangements, part of the Great Work.

As the wheel spins faster, I recall my ‘great work’. An imagined future Shaftesbury, transformed by cooperative principles, alternative technologies, revived crafts, regenerative agriculture, spiritual principles and practices not wedded to any single faith. An Aquarian utopia. All this in my head, on paper. In fact – a novel. And having read about the alchemical work of John Dee, astrologer to Elizabeth, Elias Ashmore, whose collection became the Ashmolean Museum, and Isaac Newton and his twenty years of alchemical experiments, I imagined a group taking up where their work left off (pushed aside, labeled a dead-end by rationalist science), developing a secular, practical alchemy at, and as the theoretical and ideological centre of, The Work. As I remember this, I am on the spinning roundabout that my work had become. Then, ‘life’ – family? a relationship? loss of nerve? – had intervened. Leaving a library of annotated books, and file after file of handwritten notes. Which had stopped the spinning then. Now, as on a speeding playground roundabout, I must inch my way to the centre, to the hub, and cling to it.

The column of the monument to Gavarni , a nineteenth-century illustrator, is decorated with figures from the Carnival, the wild pre-Lent days of a world turned upside down, including a woman in trousers, illegal at the time. It replaced, in 1911, a fountain, with a trough for the horses labouring up the hill. And it was here, during the 1841 Carnival, that Gérard de Nerval, about to spin out of control, saw the star.

First he saw Death – not unusual at Carnival (he is a carved spectral figure on the Gavarni monument). But it triggered in Gérard a series of visionary experiences, including the Angel in Dürer’s Melancholia 1. (In Renaissance Neoplatonism the planet of Melancholy is Saturn – under its influence the imagination may be inspired to great artistic achievements.) Gerard saw a star, sure it was Saturn, and set off towards it, telling his companion, ‘I am going to the Orient!’ Through the streets, in and out of vision, growing larger, red in a blue halo. At last he stopped, “proceeding to shed my earthly garments … standing there with arms outstretched, I waited for the moment at which my soul would separate from my body, magnetically attracted into the ray of the star.” But then “my heart seized with regrets for the earth and those I loved,” the star released him “to redescend among mankind.” All this while the Carnival proceeded around him. The night patrol took him to their station and treated him well until his friends arrived. The next night, while dining with friends, he asked one for the ring he regarded as an ancient talisman. “I slipped a scarf through it, which I knotted around my neck, taking care to turn the stone – a turquoise ” (symbol of protection, good fortune and healing) “ – so that it pressed against a point in my nape where I felt pain. I imagined that it was from this point that my soul would exit when the star I had seen the previous night reached its zenith and touched me with a certain ray.” An uncanny prefiguring of an event 14 years later, less than a mile away. In those years he wrote the works which influenced the Surrealists, especially Breton, and for which he known today. All the quotations are from Nerval’s Aurelia.

The neo-Classical church of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette was built 1823–36 to serve the growing middle-class population of New Athens. A Notre-Dame-de-Lorette chapel had been built in 1645 to serve the new village of Porcheron. It was also called the chapel of the Cabaretiers, the innkeepers setting up guingettes just outside the city. It was nationalised in the Revolution, and demolished in 1793.

The devotion to the Virgin is everywhere. Gérard came here during a later crisis, “where I threw myself at the feet of the altar of the Virgin, asking forgiveness of my sins. Something in me was telling me: the Virgin is dead and your prayers are useless.” A old man sits, buried in devastation at his loss. A woman comes and sits beside him, comforting in a professional way, caring, trying to read him, to begin to draw him out of his darkness. He smiles, the smile of one safe behind his wall of self-protection. Or maybe he is a helper at the church and she is asking him about his sick dog. I see an M with a mason’s mark in it, a rose in a cross … time to leave.

I walk down rue St-Georges, the one street on the Right Bank that runs north – south along the Meridian, to Bvd Haussmann.