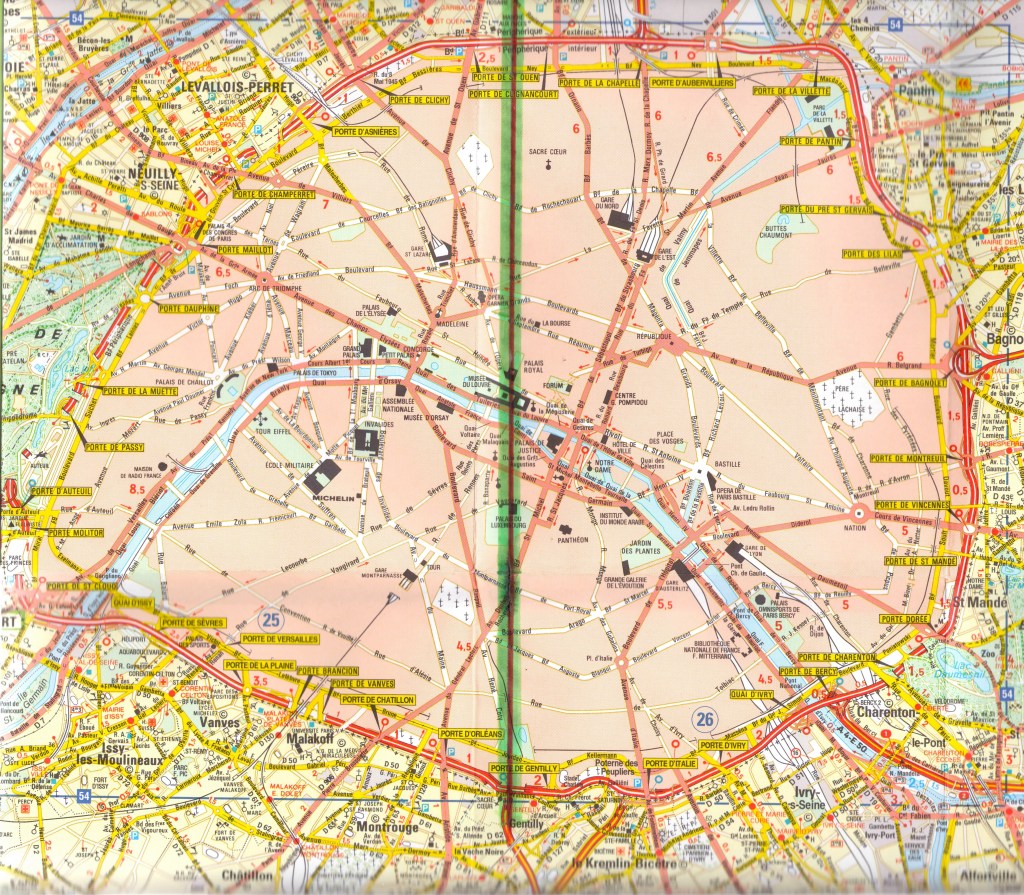

I am standing on the Paris Meridian. (A meridian is an imaginary line connecting the north and south poles of a sphere.)

The Paris Meridian was decided upon 6.6km (20,317 pieds de roi, in those days) south of here, on Midsummer Day, 1667, when members of the Academy of Sciences gathered to outline on the ground their new observatory. They designated the line of longitude through the middle of it, ‘The Paris Meridian’.

The Meridian has been used to measure the size of the earth, the size of France, to map France, and to define the metre and from it the metrical system of weights and measures.

In 1884 France finally accepted the Greenwich Meridian as 0º, rendering the Paris Meridian, 2º 20’ 14.025” east, redundant. Although for years it was nostalgically printed on French maps.

A revival came in 1994, when one of the Meridian’s surveyors, François Arago, was memorialised with 121 brass medallions set into the ground along the Meridian across Paris.

This was reinforced when for the Millennium the Paris Meridian was designated La Méridienne Verte, to be marked across France, from Dunkirk to the Pyrenees, with a line of trees. Some replacement Paris medallions record this.

It is this line I followed for my book, In Search of France’s Green Meridian. ( In MY BOOKS in the drop-down menu.) My ride across Paris took an hour, and filled six pages of the book. I was aware how much more I knew about Paris, and wished I’d had the time to include. I was like Limpy, the Aboriginal Australian in Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines, recounting the story of a songline ever faster to get it all in as he travelled in a jeep instead of at walking pace. I had gabbled through Paris at twelve miles an hour. Whereas Paris is a city to walk. The home of le flâneur. This will be the account of a slower crossing of a city that, given time and space, unpacks like an exercise in spatial geometry, expands like a Japanese paper flower. The line rarely follows streets, so I will zigzag across/meander around its 9.5km, 5.9ml length.

Interest in the Meridian was stimulated in 2003 when Dan Brown called it The Rose Line, and wove it fancifully into the plot of The Da Vinci Code.

From le Périph to the Mir du Nord.

Towards me comes the coffin of Suzanne Valadon, accompanied by Picasso, Braque, Derain, and her son Maurice Utrillo, heading for the St-Ouen cemetery.

Towards me walks Christian missionary Denis, carrying his severed head which continues to preach a sermon. He will lie down at Catolacus, later St-Denis.

Towards me walks Genevieve, carrying the stones with which she will enshrine Denis, establishing the St-Denis Basilica, where Archbishop Suger will invent the Gothic, and where French kings will be buried. Denis and Genevieve become the patron saints of Paris.

Close by is rue Gérard de Nerval, a familiar along the meridian.

But, begin with the Arago medallions. The first should be here, 50m inside the Périph, the second a few metres further. The first was lost when a library was rebuilt, the second when the pavement was repaired.

Here I pay tribute to Chris Molloy, who in 2007 located all the medallion sites on a map. (Search: ‘Chris Molloy Arago’.) Even then many were missing, and I found more gone since, so I have followed his map, without too much attention to the medallions in the ground. However finding them was like being ‘home’ – as we had ‘home’ in our childhood games.

Inside the line of the Wall, as it was being demolished in 1920s, Paris was for the first time building social housing, HBMs, Habitations à Bon Marché, mostly built by charitable organisations. Eight-storey blocks of airy flats among grass, trees and social facilities, in layouts influenced by Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities. Finished in brick in arts and crafts style, they are an attractive entry into the city. Evidently working much better than the HLMs in the banlieues, government housing projects half their age. They are an example of how low-cost, high-density housing can work. A century on, they are being upgraded to meet 2030 energy-efficiency targets.

South of the HBMs is Bvd Ney, one of the Boulevards of the Marshals, named for Napoleon’s marshals. As the Thiers Wall was being built, roads were made inside the Wall to service its defence; as it was demolished, the roads were widened to become an outer ring of boulevards. A tramway along the central reservation is a new ring around the city.

And just south, in a cutting between Rue Leibnitz and Rue Belliard is yet another ring, la petite ceinture, a railway built to service the Wall, to connect the mainline stations, and to move freight and, increasingly passengers, around the city before the metro was built. By 1900 it was carrying 39 million passengers. It declined rapidly as the metro was developed from 1900, with passenger services ended in 1934. Although freight was carried to 1980s.

Abandoned to vegetation, it became a liminal place, where eccentrics set up camp, flash parties happened, and the intrepid explored the long dark tunnels. Recently, partly responding to new squatter camps, the authorities have reappropriated it, designating it a linear green space, cleared it, and are enabling, in selected places, legal access. Below me, one rail line is now a cycle path, the other a footpath. There is access down, according to a sign, open 09:00 to 19:30: except, at 11am it is locked up, an inaccessible green way. I lean over its emptiness, people it with strollers and families, small children in enormous helmets. Then hear the rumble of bicycle wheels, the whirr of of transmissions, heavy breathing, bangs of handlebars, bumps of shoulders, the rising noise of a close-packed peloton, filling the trench, the thump of air as they pass, perilously overtaking on the track-like side wall, rising higher as the trench curves into a black tunnel, gone. Phantom cyclists, disappearing inside tunnels, reappearing on the vestigial tracks across canals, eaten at cannibal camps, joining endless freedom parties. The path is empty.

Near la petite ceinture, at 112 Rue Championnet is Bistro La Renaissance, which Quentin Tarantino found so little changed since Michel Deville in 1974 and Claude Chabrol in 1984 filmed there, that in tribute he shot the only scene in Inglourious Basterds filmed in France. (Obsessives search in vain for Le Gamaar, the Paris cinema where (spoiler alert) Hitler died: it was a studio set.)

I turn round, face south, into the sun. Ahead is a shallow and then a steep rise up to Montmartre. In the 1865 novel, Germinie Lacerteux, the heroine and her lover headed towards me. Having joined “the stream of Parisians from the suburbs all in a hurry to drink in some fresh air, they walked towards the open stretch of sky which awaited them at the top of the rise [of Montmartre], came upon the first tree, the first leaves … in the distance stretched the country, sparkling and vague, lost in the golden haze of seven o’clock … They walked downhill, following the blackened pavement of the long walls and lines of houses broken by the gaps of gardens … The descent came to an end, the paved road broke off … And Paris came to an end and there began one of those dry landscapes which big towns create around them, that first zone of suburbs intra muros, where Nature is parched, the soil used up, the countryside sown with oyster shells … Soon there rose before them the last street-lamp, hanging from a green post … They arrived at those big trenches, squared excavations, with their criss-cross of small, worn, grey paths. At the end of that you turned to cross the bridge [over la petit ceinture] past that evil encampment, houses built out of materials stolen from demolitions, reeking of the horrors they concealed, these hovels … she could feel all the crimes of Night crouching there.” Thus Paris north of Montmartre, out to the fortifications and the Zone.

And Baudelaire at the same time was writing:

“Through decrepit neighbourhoods on the outskirts of town, where

Slatted shutters hang at the windows of hovels that shelter secret lusts;

At a time when the cruel sun beats down with redoubled force

On city and countryside, on roof tops and cornfields,

I go out alone to practice my fantastical fencing,

Scenting chances for rhyme on every street corner,

Stumbling over words as though they were cobblestones,

Sometimes knocking up against verses dreamed long ago.”

Again the liminal world. Then, between city and country, with squatters in The Zone. Now, between city and banlieue, with the homeless under the périph. And just east along Bvd Ney, at Clignancourt, is an area Hazan describes as “an intermediate zone, chaotic and bustling, in the smoke of kebabs and grilled maize … a piece of the Third World, an oasis of disorder at the edge of a city that tolerates it less and less.”

Rue Belliard, by la petit ceinture, was the last refuge of Jacques Mesrine, bank robber, kidnapper, murderer and folk-hero; he was shot by the police in 1979 as he left the house.

By the time Van Gogh painted the decaying Thiers wall in 1880s, this area was being built up quickly, with workshops and houses. But very poor. So that by 1902 Rue Damrémont (the road I’m walking up to Montmartre) was described as the most densely populated quarter of Paris, with free or subsidised lunches for all pupils, its mean lives described by Céline in Journey to the End of Night. In 1901 novelist and literary theorist André Malraux was born here.

There were several reasons why Paris was known as ‘The City of Light’. One was that in the Haussmann boom, 1853 to 1870, buildings were built of the almost white limestone (originally from the underground quarries south of the Seine. Now specified by Haussmann, as it would have to be brought into the city, and therefore could be taxed), or rendered with white Montmartre plaster (plaster of Paris.) Imagine the contrast to London of 1860s! Haussmann decreed that buildings must then be cleaned or painted every eight years.

The law was long neglected, then renewed a century later by Malraux as Minister of Cultural Affairs under de Gaulle. This has relaxed to 20 years, with the cleaner air, but buildings are often seen draped in sheeting, sometimes with the façade of the building printed on it or, in prestigious locations, with high-end advertising, and are cleaner than in comparable cities. The cost of cleaning is factored into apartment prices.

The road has been rising, and at Rue Caulaincourt becomes steps which, passing a first metro station – where the exit is so steep, one leaves “as if hurled into space”, as Hazan puts it, take me up from anonymity into – ‘Paris’.

Tables on wide pavements outside cafés, streets paved with lively fans of Breton granite setts, vivid-leaved plane trees with peeling bark growing out of circular grills of patterned iron, a triangle of tree-shaded dusty earth, with old men, benches and boules, a Morris advertising column, a newspaper kiosk that folds out in the morning and back in at night, all painted dark green. It lacks only a Wallace fountain.

I have my first coffee, the indulgence of a grand crème. I am boning up on Morris columns when the young aproned waiter comes out, says urgently to two women sat together, ‘who is wearing Miss Dior?’ A demand and an appeal. Neither is. ‘It reminds me of my girlfriend, she broke my heart, it’s four years now.’ Has she just passed, leaving that fugitive four-year old trail? the exact combination of skin odour and perfume that takes him only to her? has he just missed her? An unusual performance from a seen-it-all waiter, but, France, Paris, Montmartre. At all the tables, our collective shrug, c’est la vie.

Up again, towards the Mire du Nord, the highest point.

But now two routes – straight up steps; or a curving road. For completeness I must take both. First the road.

Into the twentieth century, with most of Montmartre already built up, this was a large area of scrubland, called the Maquis, the long-neglected grounds of the Chateau des Brouillards, where over the years a mix of squatter huts, smallholders’ shacks, and artists’ studios – one of them Modigliani’s – had grown up. Jean Renoir, son of the painter, who lived close by, remembered watching goats browsing on wild herbs. On a sandy area called The Beach, Isadora Duncan and her barefoot troupe danced in the dawn.

On it, Avenue Junot, a horseshoe road from Rue Caulaincourt was built 1910-12. It was named for one of Napoleon’s wilder generals, called ‘the Tempest’, who in a mad fit jumped out of a first-floor window, then tried to saw off his broken leg with a kitchen knife, before expiring.

It curves past the Villa Leander, a row of individual houses that would not be out of place in Hampstead.

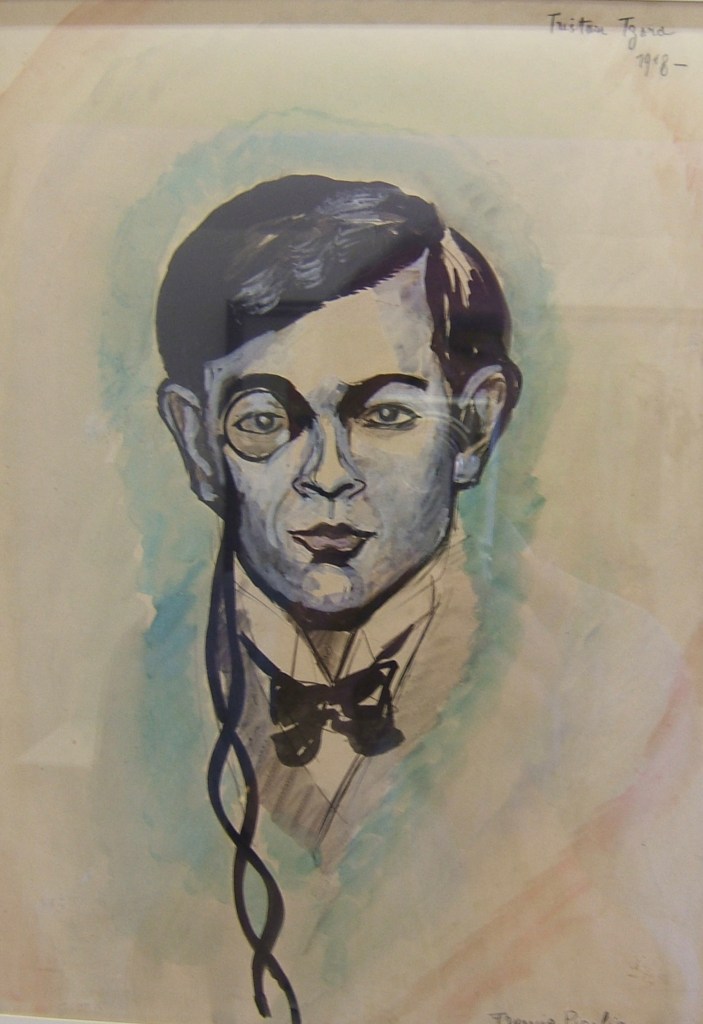

And Tristan Tzara’s house. The penniless Tzara, having ‘married well’, had this modernist house, by Austrian architect Alfred Loos, built in 1925. Although Loos lived and taught in Paris for several years, it is his only building in France. Tzara, animator of Dada in Zurich, had arrived in Paris in 1919, and soon became active in Surrealism, working closely with André Breton. [Off the avenue is Rue Simon Dereure, where I find my first Arago medallion.] Junot curves round to the highest point of Montmartre, of Paris, the Moulin Blute Fin, the Meridian marked by the Mire du Nord.

But now to return to the start of Avenue Junot, and climb the 51 steps to the bust of Dalida.

Dalida was a hugely popular recording and performing artist in France and Europe from 1950s to 1980s, with a publicly-lived and tragic personal life – four of her lovers killed themselves, as did she. Now she stares defiantly out at the icing-sugar confection of the Sacré-Coeur basilica, her bosom polished bright by the superstitious touch of adoring fans.

Close by is the Chateau des Brouillards; the mists formed when the warm artesian spring welling up from 600m deep condensed in the cooler air. It was a well-used watering place for animals, and a mystery, a spring at the top of Paris’ hill.

The chateau was one of the ‘follies’ that “Louis XV nobles built in out of the way places for their licentious parties. It was the fashion.” (Zola, La Curée, p251). Neglected after the Revolution, the vineyards and gardens ran wild, and it became the Maquis.

From here Gérard de Nerval reminisced in 1851: “ten years ago I could have bought a small property here for 3000 francs. Now I’m asked 30,000. What seduced me in this small space, sheltered by the tall trees of the chateau, was this remnant of a vineyard linked to the memory of St Denis, who from a philosophical point of view was perhaps a second Dionysus. It was then the neighbourhood of a watering trough which in the evening came alive with the show of horses and dogs that are watered there, and a fountain built in the antique style, where the women chat and sing while they do their washing, as in the early chapters of Werther … An admirable place of retreat, often silent. Don’t think of it, I will never be an owner. I would have such a light construction made in this vineyard! A small villa in the taste of Pompeii, with a shrine to the deity, like The House of the Tragic Poet.”

There is so much of Gérard here, who we will meet several times: the implicit apology to his father for not having settled down; the nostalgia for his childhood in the rural Valois north of Paris; his literary references (he published an acclaimed translation of Faust at 19); his pantheistic religion, connecting Denis, patron saint of France, with a Greek god: (when, after a long discourse at Victor Hugo’s house “whirling together the Heavens and Hells of several religions” (Gautier) he was charged with having no religion, he replied, “no religion? I have seventeen religions, at least”); his exoticism, a Pompeian house with a household shrine; and this while looking out over Montmartre cemetery where was buried Jennie Colon, the passion of his life, for whom he expended his inheritance without ever declaring himself.

Adjacent is the Square Suzanne Buisson, named for a Jewish socialist and Resistance activist who was murdered at Auschwitz. There is a statue of St Denis. After his beheading nearby – when the Roman Hill of Mars became the Christian Hill of the Martyr – he carried his head to the mysterious spring here, washed it, and then walked on 6km, to lie down, where St Genevieve built his tomb and established the St-Denis Basilica. Which became the centre of French Christianity, and where Abbot Suger built the first Gothic building. (There’s a full account in my In Search of France’s Green Meridian, Day 6, read in drop down menu MY BOOKS.) The spring is now dry; this fountain is supplied by the municipal water system.

Having climbed so quickly out of the undistinguished northern suburbs, I want to stop here, just this side of the highest point, before the plunge down into ‘Paris proper’, to dwell for a while on this quiet, sunny Sunday morning, in this swirl of interest.

Here is the St-Vincent cemetery, where Marcel Carné, Marcel Aymé and Maurice Utrillo are buried.

Carné the director of the classic film Les Enfants du Paradis, written by his long-term collaborator, Jacques Prévert.

Marcel Aymé wrote Le Passe-Muraille: a clerk finds he can walk through walls. At first he uses his ability to unhinge his boss. Then, extending into crime, he becomes wealthy enough to move into Ave Junot. He begins an affair with a married woman in nearby Rue Norvins. But when his power wears off, after mistakenly taking an antidote, he is trapped in the wall. In Place Marcel Aymé a sculpture represents him half in and half out of the wall.

Passing between worlds, what is a wall for others is a doorway for him, returns me to Gérard de Nerval. He opens Aurélia, his final work (Aurelia is Jennie Colon) with, “Dream is a second life … [in sleep] the spirit world opens for us”, a gateway to what he calls the external world, where he has visionary experiences in a world as real as the material world. (Breton wrote of surrealism as “the seepage of dream into real life”, and of Nerval as a forerunner. In the Surrealist Manifesto, pulling back from Tzara’s “thought is made in the mouth”, he writes, surrealism “proposes to express verbally the actual functioning of thought, with no control by reason.” But surrealism is born of psychoanalysis, in which dreams would be ‘interpreted’. Whereas Gérard’s is a pre-rationalist visionary world, the world as depicted by Apuleius, Dante, Swedenborg, of visions to be lived.)

So permeable was the membrane between material and visionary worlds for Gérard that often the visionary was for him more real, when “I seemed to know everything, understand everything; my imagination afforded me infinite delights. Having recovered what men call reason, must I lament the loss of such joys?” (Aurélia. I.) It resulted in behaviour, as we shall see, that landed him several times in psychiatric clinics, where he often vehemently refused to acknowledge that he was ill. The first clinic was in nearby Rue Norvins, which he recalled as “located on an elevated spot and had a large garden planted with rare trees … I was enchanted by the vividness of the first sycamore leaves … the vista overlooking the plain afforded delightful prospects.” But followed by, “I peopled the hills and the clouds with godlike figures whose shapes seemed to appear distinctly before my eyes.” (Aurélia II) It is this ready passage between worlds, not available to others, that so enriches his writing. But the passage was so ready, as in Le Passe-Muraille, that he progressively lost touch with this reality, with tragic consequences. It was in the clinic at Rue Norvins that he dropped his father’s name, Labrunie, and becomes de Nerval, his uncle’s paddock in the Valois, where he lived as a child. (There is more on Gérard in the Valois in my In Search of France’s Green Meridian, Day 6, read in drop down menu MY BOOKS.)

Maurice Utrillo was the illegitimate son of Suzanne Valadon. Valadon, christened Marie-Clementine, was brought up in poverty in Montmartre by her unmarried laundress mother. By 15 she was an acrobat in the Circus Fernando at Place Pigalle, but a fall ended her career. Named Suzanne by Toulouse-Lautrec, she began a career as a model for the artists who painted at the circus, Toulouse-Lautrec, Morisot, Renoir, Degas. She lived for a time with the eccentric composer Erik Satie in Ave Cortot, in a room so high “I can see to the Belgian border”. When she moved out, she left him with “nothing but an icy loneliness that fills the head with emptiness and the heart with sadness”. He moved to Arceuil, at the southern end of the Meridian, although continuing to walk nightly to Montmartre to play piano in le Chat Noir and other clubs, the rhythm of his walking stick providing the pulse of his compositions. As long as he didn’t stop at too many bars on the way. She moved on.

Helped by the artists she modelled for, especially Degas, she learned to draw and paint. Marriage to a stockbroker enabled her to paint full-time and have a successful career, painting both men and women from a novel female perspective. A resourceful woman she negotiated her way through life as a poor woman in a man’s world – at 49 she divorced her husband and married her son’s 28-year-old friend. It is a loss that there has not been a film of her life – played by Jeanne Moreau in her prime. Her studio on Ave Cortot is now the Museum of Montmartre.

Maurice, troubled by schizophrenia and alcoholism, was taught to paint by his mother to occupy him. He quickly became successful, as the quintessential Montmartre artist, with postcards of his art everywhere. In middle-age he became fervently religious and moved out of Paris. Just before she died, Suzanne arranged for her friend, Lucie Valor, to marry and care for him. Lucie kept him painting, and controlled his drinking, and he lived to 72.

By the St-Vincent cemetery is the Lapin Agile, a rough cabaret-bar in 1860s that by 1900 was a rendezvous for artists and writers. In 1905 Picasso painted Au Lapin Agile in return for food and drink. He depicts himself as Harlequin, looking helplessly down at his absinthe glass, next to Germain Gargallo, dressed as a courtesan, blank face looking resolutely ahead, seeing her next mark, with red on her lips and red – blood? – on her hand, the woman over whom Picasso’s best friend had killed himself, who is now his lover, and with whom he will stay in touch until her death in 1948. A stunning painting, and one of the saddest I know. The proprietor sold it in 1911, as Picasso was becoming known; it sold for $60,000 in 1952, and in 1989 for $40.7 million.

With relief I turn to the scene around me – Paris’ last vineyard.

Sunlit, vivid green leaves fluttering, stepping gracefully up the hill. From the time when Montmartre was a village of quarries, vineyards, and windmills.

Being outside Paris until 1860, and especially outside the Farmers-General tax Wall, it was freer and cheaper, and became a leisure destination, with bars and dance halls. The Moulin de la Galette was so called because it served the local flat cakes.

Even after incorporation into the city, it was independent-minded enough to be the place where the resistance that led to the Commune started in 1871, when the discredited government forces tried to appropriate the canon on the Butte.

The two-month Commune was framed as a new Revolution, taking up where the 1789 Revolution had failed, an idealistic temps des cérises, celebrated ever since, and echoing through the May 1968 Evénements. It ended in la semaine sanglante, with over 9,000 Communards killed, many by firing squad – bullet holes pit the wall of the Père Lachaise cemetery, where 266 were shot and dumped in a mass grave. The Sacré-Coeur basilica was built at the city’s highest point by the religious right in expiation of the Paris’ ‘sins’: losing the war, and establishing the Commune. It is a tradition among working people passing it to spit, ‘long live the devil!’. In 2004 the square in front was named for Louise Michel, prominent Communard and later anarchist, by the mayor of Paris.

To return to the Meridian. At the top of Ave Junot is a private path into the grounds of the Moulin Blute-Fin, where at this conveniently high point on the Meridian, Jean Picard placed the first mire or sighting post for the measuring of the Meridian across France, to begin the first accurate survey of Louis XIV’s realm. The Mire du Nord, replaced in 1736 by a stone monument, is inaccessible in a private garden.

I have crossed the summit. No more ‘views to the Belgian border’. Now the panorama is all Paris.