A Walk across Paris along the Meridian.

St-Ouen.

Outside le Périph. A large silver ball has landed on a small traffic island. The sun blazes at its centre. Mirrors reflect; a curved mirror bends. And eventually deflects. Passing cars appear, swell, are gone, into St-Ouen. “St-Ouen Bienvenue.”

Under Napoleon III, I see a marshal of France on horseback, sabre raised. Between the wars, in this banlieue rouge, I see an heroic worker, hammer raised, stepping forward. In 1950s, a kinetic sculpture in stainless steel, Jacques Tati scratching his head and then becoming helplessly entangled in it.

Now, for the Millennium, a large silver ball. A reflecting emptiness. A perfect form, without content or meaning. Attempt a meaning and it will be reflected back to you, distorted in a mathematically explicit way. Or it will slide away to oblivion. “Meanwhile abstraction has invaded all the arts, contemporary architecture especially. Pure plasticity, inanimate and storyless, soothes the eye,” Ivan Chtcheglov was already writing in 1953, in Formulary for a New Urbanism, the founding text of The Situationist International.

Le Périph (boulevard périphèrique) is in front of me. Eight lanes of traffic, 240,000 vehicles a day, thundering past at bedroom height, the height of the Thiers Wall around Paris that it replaced. (In the wealthier areas it has been expensively tunnelled.) I am by the marché au puces, closed today, and displaying a multi-coloured blankness of graffitied metal shutters. Just one establishment is open, ‘Armurerie, Materiels d’Espionage, Materiels de Défense’. Everything in the heavily-grilled window is matte black, sucking in the light. Inside a black dog with dagger teeth and a spiked collar.

Next to it is an abandoned concrete restaurant, Le Stromboli, Betty Blue I love you!, their time working there, Betty waiting for his novel to be published, Zorg wanting only to be with her.

On the first-floor terrace, level with the pollution-pumping roadway, the plants have run wild, filling the terrace and flowing over the roof. Chemically-induced mutations? I expect to see blue monkeys howling! DayGlo parrots squawking!

Next door again is a small detached house, in the neatly-decorated French version of Arts and Crafts, rendered and painted ochre, with a red tile roof. On the tin letterbox, “Mme Plasy, Violette.” There are red geraniums on the balcony, and a black cat snoozing as the traffic thunders past.

The Thiers Wall

was the seventh wall built around Paris, as the city expanded from Roman times. It was built in 1840s, after the shame of 1814, when the one day ‘Battle of Paris’ ended with the victorious Prussian generals dining that evening in the Palais-Royal. It enclosed an area twice the size of Paris. In 1860, to enable Haussmann’s grand plans to be carried through, the area was incorporated into the city. ‘Paris’ has not grown since.

The wall proved ineffective in 1870, when the Prussians blockaded the gates, and starved the city into surrender. The Wall was neglected, and demolished in 1920s.

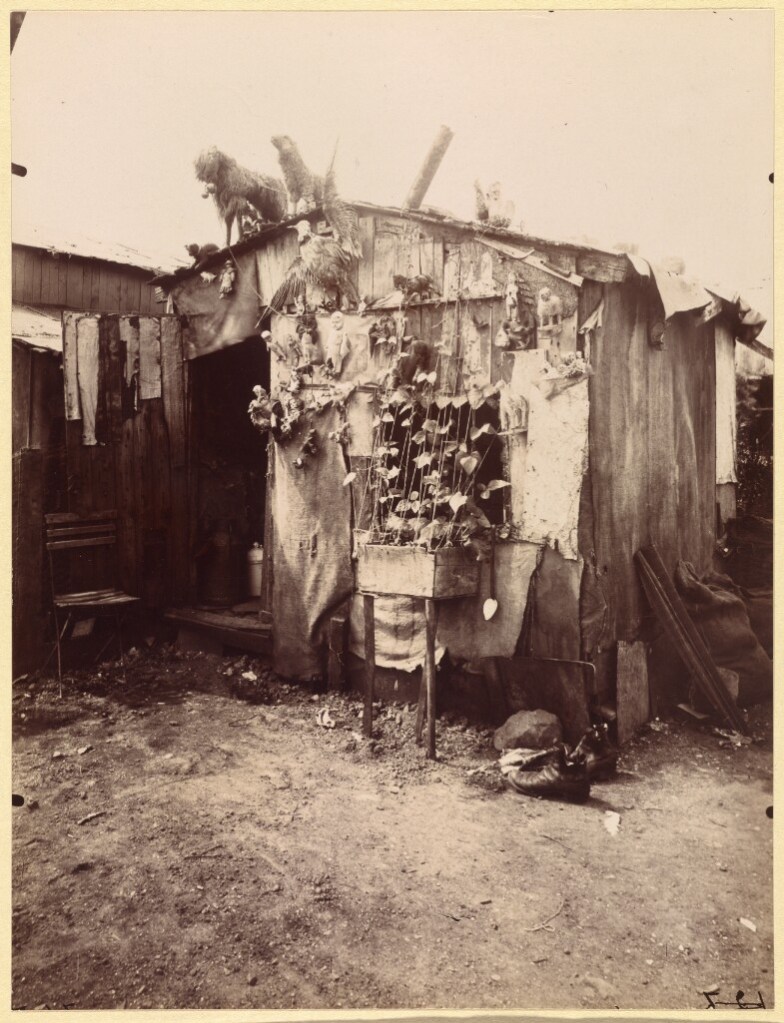

The area outside the Wall was called ‘The Zone’, where no building was allowed. But gradually, as the Wall was abandoned as defence, the homeless colonised it with shanty towns. Many were chiffonniers, ragpickers, progressively pushed out by Haussmann’s rebuilding.

Chiffonniers collected Paris’ rubbish and recycled it. Essential both in clearing the streets – before 1883 Parisians were allowed to dump their rubbish in the street between 7pm and 7am – and in supplying necessary raw materials. Rags were made into paper, bones used to make buttons and handles, bone char to refine sugar. The municipality called their work “repulsive but necessary”. There were 30,000+ in 1875. The poorest in society, but noted for their independence and, working at night with basket, hooked stick and lantern, mysterious.

They had been marked out, in his 1848 play by revolutionary writer Felix Pyat, as representative of ‘The People of Paris’, a potential threat to the given order. For Baudelaire they are like the flâneur-poetes in their careful gathering and sorting and transforming of the discarded into the useful. Also when reeling home drunk, they transform the city, as poets do: “banners and garlands and triumphal arches loom by solemn magic before their eyes.”

And there was the direct relationship of chiffonnier and writer: the rags they collected went to make paper for the rapidly-growing newspaper and book trades of those who wrote about them.

However, poor and powerless, their slums within the city were targets for redevelopment during the relentless Haussmanization of the city from 1853. And technology replaced rags with wood pulp, and bone with celluloid. Rubbish became a waste to be got rid of, rather than a resource to be processed.

A decree of 1870, and Poubelle’s reforms of 1883, requiring each household to have rubbish bins, forced the chiffonniers out to the Zone, in Saint-Ouen. There they were romanticised by bourgeois writers as independent ‘philosopher-kings’, anti-establishment heroes. (As tramps were in Edwardian England). Whereas activist-photographer Atget registered their real poverty.

Perhaps with rising affluence, perhaps because people still needed to get rid of what wouldn’t fit into their poubelles, the chiffonniers developed a new aspect to their trade – sorting for reuse rather than recycling. They sold these saved articles here, in St-Ouen, establishing the first ever flea market, marché au puces. It is now the largest concentration of antique dealers in the world.

St-Ouen marché au puce

In 1927, when it was still conducted from stalls in the street, Surrealist writer André Breton “went with Marcel Noll one Sunday to the Saint-Ouen flea-market. (I go there often, searching for items that can be found nowhere else: old-fashioned, broken, useless, almost incomprehensible, even perverse.)” There, “our attention was draw to a brand new copy of Rimbaud’s Oeuvres Complètes, lost in a tiny, wretched bin of rags, yellowed nineteenth-century photographs, worthless books and iron spoons” (Nadja p52). Inside the book were poems, written by the girl running the stall, Fanny Beznos. Her family were Jewish immigrants. She became part of the Surrealist circle, before being exiled to Belgium, and in 1942, dying in Auschwitz.

Gabrielle brought me here in 1976. On a similar stall we found a copy of Jacques Prévert’s Paroles. We’d quoted the poems to each other when we first met. The pages were loose, falling out. We placed it carefully in a dome-topped cage of thin bamboo, and took it back to the apartment overlooking the Beaubourg square. We folded each page of the book, except one, into aeroplanes which we launched over the square, watching as they swooped and spiralled, as passers-by picked them up, read, discarded, placed carefully in pockets, sat down to read, looked up, wondered.

Then we took apart the cage, used the bamboo sticks to read the I Ching, and employing the vannier techniques my neighbour had taught me in rural Aveyron, I made a bowl in which we place the saved page, Pour Faire le Portrait d’un Oiseau, ‘To Paint the Portrait of a Bird’. Which reads (Ferlinghetti’s translation)

First paint a cage

with an open door

then paint

something pretty

something simple

something beautiful

something useful

for the bird

then place the canvas against a tree

in a garden

in a wood

or in a forest

hide behind the tree

without speaking

without moving . . .

Sometimes the bird comes quickly

but it can just as well spend long years

before deciding

Don’t get discouraged

wait

wait for years if necessary

the swiftness or slowness of the coming

of the bird bearing no relation

to the success of the picture

When the bird comes

if it comes

observe the most profound silence

wait till the bird enters the cage

and when it has entered

gently close the door with a brush

then

paint out all the bars one by one

taking care not to touch any of the feathers of the bird

Then paint the portrait of the tree

Choosing the most beautiful of its branches

for the bird

paint also the green foliage and the wind’s freshness

the dust of the sun

and the noise of insects in the summer heat

and then wait for the bird to decide to sing

If the bird doesn’t sing

It’s a bad sign

a sign that the painting is bad

but if it sings it’s a good sign

a sign that you can sign

so then, very gently, you pull out

one of the feathers of the bird

and you write your name in the corner of the picture.

We wrote our names in the corner, and ‘merci’, for the young Jewish doctor – born when her mother was on the run in southern France, she works too hard in a clinic for immigrant women – who had lent us the apartment. Gabrielle kept in touch with the girl running the St-Ouen stall. The last I heard they were in the South, continuing the rural life she and I had briefly shared.

The Saint-Ouen marché au puces is now the largest concentration of antiques and second-hand dealers in the world, with five million visitors to several halls and dozens of stalls. There are Michelin Men, in every size, configuration (the water-skier my favourite) and material, as each new material was invented. Imagine one by Jeff Coons! A life-size cut-out tin cyclist being chased by a cut-out tin dog. A table of coins with square holes, next to a giant stag in rusty iron. A VHS of Don Giovanni, directed by Joseph Losey. A pair of 2CV doors – is he selling the car piece by piece? A Maison de Chaise in which nothing looks like a chair. As craft has declined and matter is digitised, we are ever more nostalgic for things, for thingness. And then we make display of it: the 2CV doors will be designed into an expensive assemblage. Irony is baked in.

“Private property has made us so stupid and inert that an object is ours only when we have it.” “All the physical and intellectual senses … have been replaced by the simple alienation of all these senses, the sense of having,” wrote Marx in 1844.

As our realities become more abstract, virtual, mediated, we are drawn to objects, especially those that can no longer be made, to console our loneliness with their nostalgic presence. They signal (not that we pay attention) that progress is not cumulative but substitutive, that with each new skill learned an old skill is lost. My brother works with his hands, with tools that are no longer made, moulding, carving, shaping, looking, feeling; no longer to make, but to recover, remember, renew the sense, the feel, the touch of making. He works with gravity. And will this walk across Paris ground me? Will I be conscious of the pull of the centre of the earth, each step? I could do it more easily on Google-Earth with Wikipedia, follow the Paris Meridian, the Arago Medallions, more accurately. But I will walk the line. I’m about to walk under le Périph.

Le Boulevard périphèrique is on the line of the Thiers Wall, and echoes it: the 37 junctions, Portes, are on the sites of the Wall’s gates. In the nineteenth century, denied access to the city within the Wall, railway yards and heavy- and factory-industries developed in the départements around Paris. Which became the Red (ie militantly left-wing) suburbs. And from the 1950s the Paris poor, rather than being accommodated within the city, were decanted into high-rise, often poorly-built social housing in these suburbs (Paris’ population declined from 2.8million to 2.1 million between 1952 and 1982). With unemployment, immigration and social problems, they became the ‘banlieues’, no-go areas of social unrest. The disaffected young there are called ‘Zonards‘.

The Wall having been demolished in 1920s, the Périph road was built from 1958 to 1973.

From Roman times as Paris, has grown, it has expanded, ring by ring, to the limit of its protective walls, then built a new wall further out, demolished the redundant wall, and replacing it with wide boulevards (‘boulevard’ originally meant ‘rampart’), uniting the ‘old’ and ‘new’ areas on either side.

This boulevard is different; it doesn’t unite the areas on either side, but definitively divides Paris from what surrounds it. Now ‘Paris’ is happy to exclude the banlieues that are by any definition part of Paris, and to live within its ceinture, its 1860 boundary. With its own view of itself, its own rules on building heights etc, and from which poorer people have continued to be forced out by gentrification. And in the process has become increasingly, as Eric Hazan, historian of Paris calls it, a museum.

The Périph is a 35km dual-carriageway road, carrying 240,000 vehicles a day. It was opened with a speed-limit of 90km/h, reduced in 2014 to 70km/h, and in 2024 to 50km/h. The average speed of traffic now is 43km/h. In 2005 a motorcyclist rode round it in 9’57”, 211km/h. The lone figure in the dawn light, between the backs of cars rushing towards them, canted over for 35km, resisting the centrifugal force – as the riders used to, in the ‘Wall of Death’ side show built here in the 1920s – two inches of soft rubber barely adhering, ready at any moment to let go, the self-defined astride the created will. Cross the timing beam, long deceleration, breathe again, check the time. Park and ease a leg over, pull off helmet, shake out the hair, red hair and black leather my favourite colour scheme, and a secret 3am smile.

I walk under le periph. A shock, in the dripping damp, under the ceaseless rumbling, to find an encampment, of pallets and plastic sheeting, dark faces and wary looks. And a return of the flea-market desperation – not items ‘collectible’, ‘pre-loved’, but worn-out, shoes, toys, cheap clothes, scavenged objects, anything that might raise a few cents, sold off dirty blankets. In one section the enormous cases in which immigrants had brought all their possessions, being sold, no return. So many of them, adding incrementally at the edges. The police walk in threes. Along sections of the Périph, sprawling shanty towns are once more growing up. There is a man, writes Jean Rolin, in La Clôture, who lives in one of the columns supporting le périph. Walling himself like an anchorite is his only security. I imagine a network of passages in the périph structure, inhabited by new troglodytes, like those in disused metro passages, and in the Catacombs. The old poverty is returning. And “poverty is a giant who uses your features like a rag to wipe a filthy world,” as Céline memorably put it. While writing the brilliant Journey to the End of the Night (1932), he was working in this area as a doctor.

Through this ragged desperation, I emerge, in Paris, into a lively and colourful street market of fruit, vegetables and flowers.