Note

The Shaftesbury Chronicles was intended to be a three-volume alternative history of Shaftesbury from 1989 to 2000, in which the town would succeed Glastonbury as a New Age centre. This would be achieved by a revival of the ancient Byzant water ceremony, and the destruction of the Town Hall. And, led by a philanthropic foundation, the development of the town as both ecologically sound, and with an economy and society making use of neglected ideas from before the rationalist Enlightenment takeover in the eighteenth century, such as alchemy, the Hermetic tradition, and the work of the Elizabethan magus, John Dee. Most of this work exists only as notes.

However, I did complete volume one, The Garden, which recounts how two local boys release a Merlin-like figure from a mental and spiritual paralysis, and with him initiate and activate the process that will enable Shaftesbury to develop as a centre for the New Age. This is the text of that story.

Volume One : The Garden

PART I

Chapter 1

It had changed, of course it had. So much had happened since. But I remembered it as it was then, had dreamed about it so often, had wanted to tell Dominique, had intended to bring her here on our first walk. And yet here I was, on my own, peering through the hedge like one locked out, and Dominique was at the Centre, being appraised by my mother, flirted with by my father, while the twins explained in grave alternations the nature of their work (their “Work”) and its importance. The statues were gone. The rampant, tangled undergrowth through which we had, with such labour, cut the paths, was now trimmed and ordered. The paths themselves were laid with bark chippings, edged with wood. There was a bench, now, over the place where we’d buried the old man. On it sat a young woman, stylishly dressed, reading intently, one of the Master’s texts no doubt, her foot tap tapping on the spot where we had laid the old man’s head. I kept watching.

It had always been a place to be frightened of. When we were little the older kids would terrify us with tales of the ogre man who’d boil you in a pot until your eyeballs popped out and your brains dribbled from your ears like muesli. When we were older, we’d tell the little ones the same stories, delighted when their lips trembled and they began to sob, then scream as we dragged them towards the rusty gates as if to throw them in. We’d watch, hands over mouths, hearts dropping into our stomachs as the treacherous wind snatched our ball and carried it floating over and we’d stare through the bars at it, shiny, perfect, inaccessible. And the next day (here early), sometimes it would be back, magically returned to our side; and sometimes not, just gone, leaving a dent in the grass.

Later, when I started my solitary walks, found that walking, just walking, was the only way I could find a space around me that felt okay, and sometimes just right – so often people, family, even friends, either came too close so I felt invaded, suffocated, or kept back and left around me a gap in which I floundered and felt desperately lonely; whereas while I was walking, the air made a transparent form around me exactly my shape – this was one of the places I’d visit. I had a number of such places, each in some way special – a horse trough half way up the steep hill where I imagined the toiling beasts taking relief; a bedroom window with a gap between the curtains; the dark silent place beneath a churchyard yew tree; a viewpoint overlooking the Vale from where I could see a dreamed-of road going somewhere. Sometimes I would plan my walk from place to place to create a crescendo, or a diminuendo, or some pattern that pleased my mood. Other times I walked quickly between them, randomly, in mindless even desperate jazz improvisations. (In my – mercifully brief – Jesus phase I called them my Stations of the Cross, and ended up outside the Town Hall where I looked up at myself nailed on the high cross, everyone screaming hatred, my parents hiding, me being beatific. Once I jabbed my palm with a compass. It hurt like hell and went septic).

I liked it, the garden, being overgrown, the bright green stinging nettles everywhere, the brambles tangling everything up, the shrubs grown wild, shooting in all directions now they weren’t pruned, unrestrained, the fruit trees all blossom and no fruit. I liked the twisted gates and the rusty chain, the pillars moss-covered, askew, ready to topple. And the eagles, on top: when the pillars fell, would they fly? No, they’d crash and smash and I’d have a souvenir, a piece of wing maybe.

I liked the grass-grown drive, the stillness and decay. I imagined a little world, self-contained with the big world locked out, in which there was no future – no expectations, no disappointments, no fears. Sometimes I’d glimpse the old man, shuffling around, muttering, envy him his circumscribed world. Twice he looked up suddenly, stared straight at me as if he could see me, (I drew back instinctively), although I knew he couldn’t, then he scuttled away.

That day, the day it began, was the same day someone was writing: “The writing of this Prophecy from Alpha to Omega is completed upon the feast day of Joseph of Arimethea and St Patrick, 17th May, 1989”. My hand pushed aside the vegetation that hung like a curtain, and I peered through the hedge – and found myself face to face with someone staring at me. I leaped back in shock. It was a girl, completely naked, very still. My heart pounded. I wanted to run away. I was used to looking unobserved. I had to see her again. I approached, peered, carefully. It was a statue, pink stone. I stared at her. She was beautiful. I imagined folding her in my arms, holding her, loving her. I imagined kissing her lips, hard and cold at first but then soft and warm, yielding , her arms reaching round, her body softening, melting into mine. I pressed through the nettles and brambles to reach her, not caring about the stings and pricks, welcoming them, the price, unstoppable. And yet, as I approached her, she didn’t melt and yield. She stared back brazenly, without modesty. I suddenly felt exposed, out-faced, ridiculed. I pulled away in manufactured contempt and walked away in pretended nonchalance, denigrating her with coarse epithets.

I didn’t know what to do. I wanted a place where there was warmth and understanding. Home wasn’t it. (There had been such a place, but that had gone three years, a lifetime, before.) Mum was only interested in her new job – in the mornings she was fresh and keen, well made-up and her hair done lovely, a strong perfume I liked, dressed really well in a slim suit and white blouse. But it wasn’t for me and dad, it was for her new job. In the evenings she’d be tired, though eager to talk about work. But dad would quickly silence her, saying he had enough work at work, it was okay for her because it was new, he was tired couldn’t she see, it was more like they shared the house than were married, bla bla bla. Mum would stiffen then apparently relax and carry on as if nothing had happened. But if, sitting on the settee watching a TV programme, he cuddled up to her she would turn to stone and he would go sullen or bang out of the room. Five minutes later there’d be the sound of his exercise bike going at fifty miles an hour and mum’d be on the phone to a friend talking too loud and laughing a brittle, unnatural laugh. The livelier she became, the deader he went. He’d gone grey, all except his hair (I found the dye bottle in his cupboard). He’d sit for hours staring at the television, criticising. Sometimes he’d try to muscle in on my interests, but I wasn’t having that. The next day I went back.

She (what am I saying? – it. She) was gone. There were two new statues, visible through the gates. Facing each other, one with his back to me, the other offset so I could see her clearly. I forgot the girl. She’d been pretty, yes, but a girl, insipid. This was a woman – beautiful, magnificent, unbuttoning her dress, revealing herself, an excited look on her face, who would embrace me and crush me to her, excite me and teach me. I pushed against the gates – I’d have toppled them, pillars and all, if necessary – the rusty chain snapped, I was through. I stepped into the garden. I walked towards her, iron drawn by the magnet in her breast.

But when I got close, I saw her eyes weren’t for me, but for the other figure. I looked at him – he was broad, heavy faced, with small horns and an enormous curved prick. I started back, away. Then I saw the leer on his face, the way his hands reached rapaciously for her. I stepped between, facing him, protecting her. I pushed against him. He didn’t move. I picked up a piece of iron from the fence and held it like a defensive quarter staff. I prodded, tapped, hit him, felt a sudden surge of power and struck him blow after blow (feeling the woman safe behind me) until he began to totter and – oh glory! – like a great tree, he fell. Bits broke off. But now my blood was up and I was raining blows on him, striking limb from torso, head from neck, waiting for the touch, the whispered thanks – enough! – the embrace from behind. It didn’t come. Blow after blow – each now resounding in a terrible emptiness, on and on. Until I collapsed exhausted, into the emptiness, across the fallen figure, looking up at the standing figure who was still reaching out. But not for me.

Great spasms began tearing at my chest. Like a fist punching me from the inside. As if a demolition ball was trying to burst out of me. As if my body was trying to turn itself inside out. Sobs. I began to cry. I hadn’t cried for years, my body couldn’t understand what was going on, resisted – then remembered, and the tears came, floods of them, in great sobbing waves. I sobbed because I was alone in the world. I sobbed until I was empty of tears. I lay sprawled over broken stone, lost.

‘Oh dear, oh dear.’ A bony hand on my shoulder. A thin, confused voice. Gusts of bad breath on my cheek. My insides turned to water. I clenched my eyes shut, held my breath, wishing (three wishes – just one wish, please) he’d go for help, go away, give me chance to escape. He wasn’t going to go away. He was fascinated by this thing that had come into his world, a strange creature washed up on his beach. Words came between gasps of breath: ‘oh dear … Dionysus slain … not by Zeus … not by Semele… no … an Endicott of the rites … doesn’t care …’

‘I do care,’ I said angrily, sitting up. ‘He … She …’ But I had nothing to say. What I’d felt had disappeared with the tears, as if into sand. I just felt empty. I looked up at the woman, now just a statue, down at the shattered god, then at the old man. He blinked watery blood-shot eyes at me. There was dried white spittle at the corners of his mouth. His teeth were brown. His breath stank. He was a mess. But instead of being disgusted by him, I felt sorry. He stooped, stroked the broken statue as if it was a dead pet. He was sad and forlorn. And lonely. I imagined the loneliness I felt for maybe half an hour, that would disappear with a nice pudding or a funny television programme, I tried to imagine that going on forever. That’s how lonely he looked.

‘Can it be repaired?’ I asked, pathetically. A little kid’s question, all wishful thinking.

‘Eh?’ He turned his blue eyes, across which expressions had been passing quickly, like reflections of clouds across a window – incomprehension, the beginning of meaning, the attempt to grasp its flight, he turned them on me. He focussed on me as if I’d just appeared. But with urgency, as if he knew he had to hold onto this one thing that was real. ‘Eh? You can’t repair,’ he said slowly, as if reading each word as it appeared, ‘such as this.’ (Pause). ‘You can only – remake.’ he chuckled, pleased with himself. Then the vagueness returned.

‘Is it valuable?’ I asked, trying to move things along.

‘Priceless.’ A wheezing chuckle, and he slapped his knee.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, because that was what you were supposed to say. He leaned towards me, looking round slyly then fixing me with his blue eyes:

‘Sorry, are you? Sorry won’t pay. How will you pay? Eh? Eh? Shall I tell your father? Shall your father pay?’ Bad breath – halitosis and alcohol – puffed into my face.

‘No, don’t tell him. I’ll work.’

‘Work, will you? What can you do, eh? Can you knap a flint or flense a fox? Can you weave a basket watertight? Can you read the runes, and have you the geomancer’s art? Can you handle axe and adze and draw knife? Eh? Eh? Or can you just – press buttons?’

‘I can work. Show me. I’m going now. I’ll come back.’ I was surprised how definitely I said all this. I started to get up and he backed away, confused again.

‘Come tomorrow,’ he said. He tried, unsuccessfully, to make it sound like a command; it was more like a plea.

‘I’ll come back.’

I turned and looked at him as I stepped out between the gates. His eyes were on me. He looked lost. Then he pulled back his cuff, stared at his wrist – he wore no watch – slapped his head as if at some forgotten engagement, and walked off.

Chapter 2

I didn’t go back the next day. But I did the day after. Not because I was scared – who’d have listened to him? – but because I wanted to. Maybe to help him. Maybe to feel needed. Maybe to have something personal and secret. Maybe just to avoid revising for my GCSE’s.

He looked surprised to see me, covered up by checking his empty wrist and saying,

‘Mm, a bit late, but in time – just in time. The storm’s about to break. You must clear the channels or there’ll be flood,’ squinting up at the cloudless sky. ‘This, you see?’ waving at a patch of overgrown vegetation, ‘tangles and tares. Spirits trapped. Set them free. everything must flow.’ I gathered from this nonsense that he wanted me to clear the undergrowth. He gave me an axe, a sickle, and a knife on a stick he called a bill-hook.

‘What, with these?’ I asked. ‘Where’s the strimmer?’

‘Mm. Strimmer. Odd word. Mm,’ he said, and wandered off.

It didn’t look much and, sure I’d see it off in an hour, I laid into it with the bill hook. I began by demolishing old Marshall’s sweet shop. I kicked open the door, the bell flying off the curve of spring steel and sliding across the floor to stop at his feet, the clapper lolling like a puppy’s tongue. I filled the doorway, slapping the massive billy club into the palm of my massive hand. I was – Robocop – half man, half machine. All avenger. Marshall squinted, light glinting off his spectacles, pulled his hand through the thin strands of his hair, cowered, whimpered ‘you couldn’t … you wouldn’t … it’s my life.’

‘I can. I will. Your life has been cheating children,’ I said, my voice sonorous and measured, rattling the sweet jars with its thunder. He’d done us all in his time – short measure, short change, sweets gone yucky. I’d been seven, just starting to go into shops on my own, had just moved here, handing my 20p for a sherbet fountain, holding my hand out for the change that never came as he shook his head saying, ‘no, it was a 10p you gave me. Perhaps,’ he added, with a malicious twist, ‘you’ve already spent the other 10.’ And smiled his thin, wet-toothed smile of triumph. I was so shocked, still so believed adults, that for a moment I doubted myself; but knew I was right – could do nothing about it. I stumbled out of the shop, the bottom fallen out of my world.

Walking home, through a world that had become suddenly enormous, monstrous, and alien, I kept repeating: ‘life should not be this unfair. When I grow up I’ll put everything right.’ Wham! A dozen sweet jars atomised, their multi-coloured contents flying as from a cluster bomb. Wham! The thick glass counter split with a single blow. Wham! The large Easter egg in the window smashed like a melon. And – ‘please, no!’ – Wham! A chocolate orange lofted into the air, slammed with perfect baseball precision through the plate glass window, the glass hanging, then falling like unhooked curtains. ‘Come in, kids. Mr Marshall is giving everything away – everything,’ I said, looking meaningfully at the sweating, drooping, nodding broken figure. My boots crunched on glass and sweets as I strode out between yelling, cheering kids.

I stood, panting, hands red raw, as my vision cleared. I looked back, at the vast swathe I must have cut. I’d hardly touched it. I’d bounced of the undergrowth as if I’d run into a fatman. It was comic, pathetic, ridiculous. The old man was stupid. His tools were useless. I stormed towards the house. He was curled up in a hammock, snoring, a thread of spittle hanging from the corner of his mouth to a damp patch on the canvas, his face content. I threw down the tools noisily. He woke with a start, smiling at me, an open smile; then collecting himself, recollecting, he shrank; before pulling himself together and slowly, deliberately, putting his feet down. It was as if he’d been dreaming he was someone else and woken to find he was just himself.

‘These tools. They’re useless,’ I said, in a ‘what are you going to do about it?’ voice.

‘Useless, eh?’ he said, rubbing his stubbly chin, the loose skin moving freely under his hand. ‘Mm,’ his eyes at first cloudy, then clearing. It was as if, hands gripping the hammock, he was, in his head, reaching out and gathering up his shredded, scattered thoughts, to piece them together to make a lost sense. It was heroic and pathetic.

‘Bill hook and axe useless. Mm. Thousands of generations. Millions of acres of forest cleared – Hercynia – thousands of acres worked as renewable resources. Now – useless.’

‘They’re out of date.’

‘Timeless. The timelessness we left behind when we stepped onto the treadmill of history, started believing the myth of progress,’ gaining a remembered articulacy. ‘Wanting a life that’s easy rather than one in which one’s at ease. The skill no longer in us but in the machine. Go on, push buttons, be a spectator all your life. Mm.’ And he turned to the side, examining the edges of the tools, tut tutting. I clenched my fists, said ‘stupid’, kicked the tools and walked off.

As I was running my red-raw hands under the cold tap, mum asked what I’d been doing. ‘Baseball. A new team’s getting together.’

‘That’s good, that you’re doing things with your friends,’ mum sure that if you spend more than two consecutive minutes on your own you’re becoming terminally weird. ‘Will you go again?’

‘Dunno. Might . Dunno.’ I dropped the towel on the draining board instead of hanging it up, and slumped down at the table.

‘Baseball,’ dad said, ‘why baseball? Cricket’s our game.’

‘That’s why everyone stuffs us.’

‘They wouldn’t if kids like you played. In the West Indies they’re playing with oranges and bits of sticks, while you’re playing an American game off the television that’s all marketing. I remember …’ Switch it off. Just look at yourself and switch it off. Four bloody Yorkshiremen. He’d hardly even played beach cricket with me.

That night I dreamed I was working at my computer when I saw a faint reflection in the screen. I turned round and a Neanderthal, all hair and skins, stone axe raised, was about to smash my head in. I woke up quick, trembling.

Chapter 3

When I got there the next day, he was sharpening the axe on a big treddle-powered stone wheel, sparks flying in long plumes.

‘You can tell by the way the sparks fly,’ he said, holding the blade against the wheel as I treadled. ‘There, see – like a pheasant’s tail. Perfect.’ He lifted and looked along it several times before pronouncing himself satisfied. He continued:

‘In Japan, an apprentice works for four years sharpening tools before he’s allowed to work on wood. But we’ve so little time. All I can teach you is how to keep an edge.’ He swept the whetstone along the blade. ‘The molecules, see – you’re stroking them out, spreading them, shaping them, thinning them to an edge an atom thick that can slice a hair. Stop often to use the whetstone. It’ll save you time.’ He tested it with his thumb. ‘Your axe would be the measure of your life – how sharp, how ready; the amount worn away showing how much work you’d done, what you’d put into your life. Your life measured by absence.’

Then he ground and honed the sickle, and handed me the two tools. ‘Axe and sickle, sun and moon, male and female; one hard and direct, one sharp and curling. You need them both. You need to know when to use each. And of course the yeoman bill-hook.’ He beamed. Then he sagged. Like a fireman’s hose when the water’s turned off. He crumpled onto the hammock, staring up at me, confused, swamped – as if he’d fallen from the thin edge of his concentration into a morass of mixed-up thoughts. He waved me away and curled up like a sick old dog.

I worked with the unfamiliar implements (but not so strange now) steadily, trying to use them as tools rather than weapons.

I threatened my ankles with the sickle, my head with a rebounding axe. I lopped and chopped and slashed. I felt as if I was burying myself in the undergrowth, like someone digging into a hillside – but when I looked back I saw I’d cleared an area, made a space, there was light and air. I was making progress.

I began to be more methodical, making separate piles of trunks and branches and brush. I differentiated sounds – the soft almost watery hush of sickle through grass, the sharper rasp through brambles, the click of branch lopping, the hard, implacable toc of axe into wood. I saw the flesh of wood laid bare; but it was necessary.

I became aware of the life in this little patch of wood, imagined the creatures having fled my monstrous arrival, now returning at my more measured presence. A slash of the sickle – and there, as if blinking in the light, a delicate crocus-like flower, purplish, pinkish, on an almost-white stem, alone, individual, hidden but now revealed in all its delicate glory, seeming to glow just for me. (I bathed myself in the “falseness in all our impressions of external things” of Ruskin’s pathetic fallacy in joyful ignorance that day). The body of a shrew, evidently dead and yet its body quivering with life – then I realised the movement was of grubs beneath the skin eating the flesh – one appeared through the ear hole; I shivered and dropped a large stone on it to conceal it forever and moved on. Fungi, food for a different sort of life. A butterfly, released from its camouflage on a fallen bough, fluttering mazily, as if drunk, then settling, sinking into another patch of bark. When I stopped to sharpen my tools – and the clean sound of stone on steel seemed to clear the air, too – I could hear rustlings, fast and slow, of creatures in the undergrowth, bird song all around, see the light brightening into beams then fading back as clouds passed, smell the green of sap, the blue of mint, the brown of earth. I imagined working with strimmer or chain saw; encased in armour, visored, deafened, all happening as on a soundless screen, at the end much done, little experienced, nothing learned.

Arms leaden, skin torn, mind fogged with fatigue, I met the tree, the big tree, the enormous tree, and with the habit of weary necessity I raised the axe – and held it there, stayed by a voice:

‘Sometimes, you know, when something stands in your path, it’s not an obstacle to be overcome but an opportunity to be taken, not a foe to be vanquished but a friend ready to help. And isn’t this tree magnificent?’

It was a voice I’d never heard before. I knew it was the old man behind me, but instead of his thin, reedy voice, this was deep and resonant, as if it was coming from deep inside a person bigger than him, someone from long ago. I opened my eyes. It was a beech tree, its grey trunk smooth and rippled, like the leg of a giant elephant, soaring up, its branches spreading wide, its roots (I could feel them) sinking deep.

‘Embrace. It has been waiting for you.’ A shiver ran up my spine, ran right through me. I wanted to run away. I wanted to fall into it. But I stepped forward, pressed against it, stretched my arms round as far as I could; felt strong arms enveloping me, protecting me, keeping me safe, strong certain arms; felt through my body pressed against the tree a dark rooted energy, a light reaching energy, ascending and descending flows of energy. I felt safe. I wanted to sink into it, lose myself in it, but it would not permit that; it would hold me, support me, give me strength; but only while my two feet were placed firmly on the ground. I held, was held, for a long time.

The tree didn’t let me down, never would. I could imagine not being an orphan.

When I turned round, the old man wasn’t there.

I’d cleared the patch of woodland, the tree at its centre.

‘Good,’ he said when I returned the tools and he’d checked the edges. ‘Tomorrow we can start work.’

That evening I gorged myself on junk food and watched every mindless television programme on offer. About ten I suddenly felt ill and just made it to the bathroom before I threw it all up. As I lay in bed shivering, mum said, ‘no baseball for you tomorrow – you’ve been overdoing it.’ When she brought hot lemon and honey, I asked her to get out my old night light from when I was small, a pottery house with the light shining out through the windows, like a beacon in the night, and to please leave it switched on. I imagined myself wandering through a wasteland, like the area I’d cleared, and coming upon this warmly-lit cottage, coming home. I sweated and shivered through the night, sleeping fitfully, dreaming a lot – weird dreams of giant exploding shrews, trees turning into snakes, a small sickle swinging at me. In the early hours I dreamed of the woman, the statue, a really hot (oh, delicious!) dream, and came in my pyjamas, which woke me up. I cleaned myself with tissues and then settled down, feeling much better, and slept dream-free to the morning. I was up, breakfasted and out before my parents stirred. It was Sunday.

Chapter 4

The town was empty. I cycled fast along clear streets between curtained houses heavy with sleep. Fast down the hill, my shape defined by the cool slipstream. I had somewhere to go. ‘Tomorrow we start work’. I skidded to a halt, nosed my bike between the gates – and stopped.

The garden was lost in thick mist. Cold, it shrouded everything. I shivered.

But not just at the mist. As soon as I stepped into the garden, I felt helplessness, hopelessness sweep over me. The overgrown garden, the dilapidated house, all of it neglected, from which for too long the spark of life had gone – what was I doing here? As if a voice was whispering, ‘don’t you see he’s a loser, this place is lost? Can’t you feel it sinking? He’ll pull you in and drag you down. Do you want to end up like him? Get out while you can.’ I thought of home, my room, my computer, my books. I looked around – nothing could sort this place out. The area I’d cleared, been so proud of – tiny, insignificant, the brambles already invading, drawing it back into confusion. This is his stuff, not my stuff.

I headed back towards the gate, feet lightening. And yet – the work I’d done, the feeling, the tree, the voice … I turned again, towards the house, determined.

I felt as though I was walking into a gale, wading through mud, hands grasping at me, holding me back, a threatening presence just behind me, doubt filling my mind. I got to the door, shaking, hammered, kept hammering until he opened it. Just a crack.

He looked terrified. His eyes twitched around, he kept flinching as if a flying creature was attacking him. I could feel its cold wings. ‘Things… fall apart,’ he mumbled, ‘anarchy loosed… slouching towards… to be born… the darkness – drops again,’ an idiotic, almost dreamy look coming onto his face, his eyes vague, as if he was going under. I shook his arm, poked him at each word: ‘Do something. You must do something!’ He looked at me curiously, as if he was having difficulty seeing me. Then he focussed – I could see myself reflected in his eyes – he recognised me. ‘Yes,’ he said, his thin hand bony but alive. ‘Yes,’ he nodded. And closed the door.

I sat on the step. I filled my mind with the feel of the tools, the smell of mushroom and wild strawberry, the look of the tree. The fog thinned, to a mist through which sunbeams shone, birds flew, cleared. The panic subsided. I looked around: it was broken, but it could be fixed.

At last he came out, walking slowly, deliberately. He was like a man I’d seen on television with Parkinson’s disease who, by focussing on each action separately, by controlling each movement with intense concentration, could prevent the wild flailings of involuntary spasms, could function almost normally. When I started to speak, he put his finger to his lips. He pointed to the tools. ‘Now we can start work.’

We didn’t speak of it for a week, not until we’d finished what he called “the preparation”. I went there every day. Why? Partly because of GCSE’s. That was like being in a sausage machine, each subject a sausage, its size your mark, being extruded one by one then shrink-wrapped and labelled. I’d already determined to do the absolute minimum to get by – now I had a reason to bunk off study leave. But also I was engaged. For all his vagueness, I felt there was a plan somewhere in his head, something buried that I, archaeologist-like, could help uncover, put together; that I could be the expression for his intention. I felt useful.

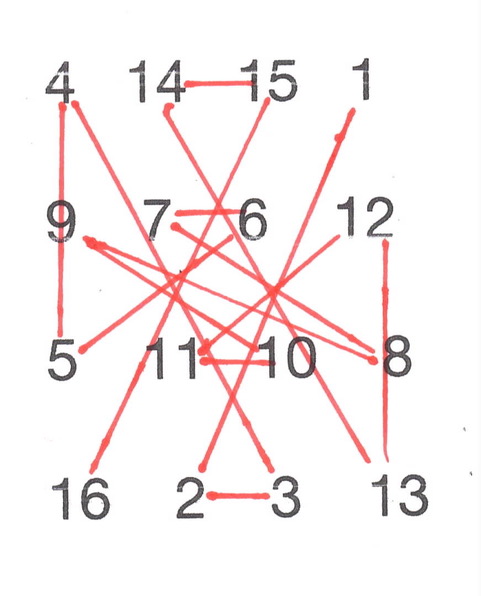

So I did what he told me, cleared where he said. Usually it wasn’t areas but paths – some straight, some curved, some so sinuous and involuted that they were like mazes. And I came upon things as I cleared – a stone with markings carved, an Aztec-looking statue, an exotic tree, a small lake almost lost in undergrowth and weed. And found new places – a grotto constructed of water-worn limestone, with, above it, a little gothic sanctuary; a classical-looking summer house on a knoll, hexagonal, all glass, mostly broken. When I asked about these, he’d stare at me as if I was speaking Martian; he was so frail, had to focus so narrowly, that nothing outside that focus made sense to him. He spent a lot of time just staring, as if trying to see what had been, or what should be, trying to remember or to envision, then moaning, stamping, smacking his head so hard I’d flinch. Sometimes he’d use a pendulum. A couple of times he brought out a compass with Chinese characters on it. Between times I’d find him curled up in his hammock in an exhausted sleep. Or swinging backwards and forwards in a child’s swing singing nonsense songs. I worked obediently, strangely trusting. And with a nice sense of playing truant, of doing something that no-one else knew about. And enjoying the physical work, getting stronger, getting browner.

The next Sunday, after walking the paths and watching the pendulum and checking alignments, he nodded and said ‘put away the tools and meet me at the summer house.’

All the doors of the summer house were open, the warm air and light filled it, and on a small table were a jug of real lemonade and a large plate of hot cakes. I wolfed through the cakes, buttery and spicy, as he sipped his lemonade quietly. His face was grey, there were black rings under his eyes, he breathed in short gasps. Then, as if calling up deep, long forgotten reserves, he pulled himself up straight and looked directly at me, smiling, his eyes shining, his hand on my shoulder, gripping it. ‘Well done, young ‘un. You’ve done good work. Without you….’ He squeezed – and then staggered, as if hit by an electric shock, the glass fell from his hand and shattered. I pulled up a chair and he sank onto it, his head down, mumbling.

‘Come on,’ I said, ‘you’d better lie down. Then I’ll go.’

‘No,’ he said, swimming through the fatigue, ‘we must talk, now. We’ve stirred things up and we must act quickly. We’ve a malefic force to deal with. And it’s only just beginning.’

Chapter 5

I’d heard such talk before, a long time (not a long time – three years – a lifetime) ago, in a world I’d closed the door on, walked away from, should walk away from now if I was to prevent that door opening, the pain – so heartbreakingly stamped on, smoothed over, sealed – returning. (You think you can do that when you’re young. But you don’t leave it behind; you drag it behind you, it slows you down, keeps you off balance, knocks you off track, poisons you. I was lucky that day, in the summer house – not that I’ve always felt it, through the stuff that followed the changes we helped precipitate that summer).

‘Last Sunday, see?’ he said, ‘I thought I understood. A number of things, all working together: the mist rising from the Vale as the sun heats it, gathering here before it’s burned off; the reaction that follows a day of action, when the novelty’s gone, both of us tired, the real hard work still to do; the effects of stirring things up – if you clear land the weeds grow quickly and profusely, and you have to keep hoeing; when you begin to meditate, all sorts of thoughts come into your mind, because the silent contemplation of nothing stirs things up, like stirring up the mud at the bottom of a clear pool in a stream – you have to keep stirring till the mud’s all gone. These things combined. But it was more than that. In clearing the paths for healing energies, we’ve drawn in a malefic force. We must find it, neutralise it.’

‘What sort of thing will it be?’

‘You know how some people get ill living under electricity lines? Well this place is sensitive, it amplifies. It’ll be recent. A satellite communication centre, maybe – there are so many satellites orbiting, transmitting, they distort the telluric forces, especially near ground stations.’

‘Of course!’ I cried, ‘Jones Hall! Jones, the financier, since the big bang and world-wide stock market trading, he’s had an enormous dish installed.’

‘You have to shut it down.’

‘What? What am I supposed to do – blow it up?’

‘Just neutralise it. I’d need two hours. I can rig up a defence in that time – but if it’s not shut down, it’d be like trying to dam a flowing stream.’

‘But what am I supposed to do?’

‘Oh,’ he flapped his arms dismissively, ‘you youngsters are into computers, and hacking – aren’t you? you’ll think of something.’

‘But that place’ll be like Fort Knox. I wouldn’t know where to begin. I only know,’ my heart sinking, ‘one person…’

‘Get him. Otherwise everything’s doomed.’

‘I have to go now.’ I slouched away, stone in my belly, knowing I had to face something I’d avoided for three years. The garden was no longer a refuge – in it I’d been brought face to face with what I thought I’d been, at last, escaping from. I didn’t look back – it was no longer just him who depended on what I did; it was me, too.

Chapter 6

I remembered the row as if it was a minute ago, the look on his face, the way he turned and walked off. Why hadn’t I called after him, run after him, put my hand on his shoulder, said sorry? You don’t when you’re young, you don’t know how to handle such things, you freeze. And you don’t believe in the irrevocable, you think things’ll sort themselves out in a couple of days. And I’m sure, too, that I was shocked by the words that had come out of my mouth unthought, unbidden, that I didn’t know what to do with feelings made real (regardless of whether true) by being uttered. Shocked, embarrassed, defensive, I just watched him, my best friend, walk away. Things didn’t just cool, they froze. Our friendship didn’t thin, it snapped, a clean break. We hadn’t spoken since. Time moved on, and our friendship disappeared into the past. And although I moved into the mainstream, had more friends than ever, while he was more than ever isolated, it was I who felt exiled, cast out.

I’d hated it when we moved here. Mum said ‘we’re only moving fifteen miles’ – but when you’re seven it might as well be fifteen thousand. It was a different world. The buildings were different, built of a forbidding dark green stone that absorbed the light, instead of the warm honey stone that I was used to, that seemed sunlit even on a cloudy day. From being in a sheltered valley with a stream, we were now in a hilltop town on an exposed dry hill. It was as though the whole of my childhood to that moment was wiped out – the ford where we paddled and fished for tiddlers, the footpath I’d learned to ride my bike on, the garden in which we’d had my birthday parties. And the house, although it was very like the one we’d left – an estate house – was the other way round, so I no longer had the sun shining round the edge of my curtains in the morning. (The breeze billowing the curtains in and flooding the room with sunlight, then dropping, and the curtains falling, and the sunlight – where had it gone? Why hadn’t it been trapped in the room to glow quietly for me? Waking early and watching for the first time, face pressed against the glass, having to keep wiping away the condensation from my breath with my pyjama sleeve, a red sunrise, terrified, awe struck, sure I was the only person who had ever seen the sun in that naked, shape-changing state, feeling ready to burst with the responsibility of holding that secret knowledge within me). Instead, it shone in the evening, making my room stuffy and keeping me awake; I’d exchanged a fresh morning sun world for a fag-end evening one. I’d moved from a world that made sense to one that didn’t. The house, the three of us, the familiar things and ways we’d brought with us, was a tiny island – like the cartoon desert island – of familiarity in a vast empty sea. I don’t suppose it lasted long – mum said I settled in within six months. But to me it didn’t last for a length of time – it just is.

And school. I’d come into existence with the kids at my first school, we’d been parked side by side in prams, wheeled together in buggies while, head to head and oblivious the mums chatted. Crawled around each other as they, still chattering, drank coffee together, gone to play school together. But here – walking into a strange-smelling school, then into a classroom of thirty five strange kids, all of them watching. It was worse than going on stage in the school play – because you never came off, there was no other world to go back to. Then you go through the process – you think you’re doing it, choosing, but later you realise you’ve been processed, sized up, it’s been decided where you fit into the scheme of things. (You watch later entrants – some come in high, all front, and then founder to their appropriate level, some start slow and move up, some come in faceless and stay that way. I’d come in angry, with fists flying). So the misfits befriend you – later you have to off-load them – and the boss kids get you into fights, test you out. And quite soon they find a label for you, and things settle down. The teachers are the same: confused until they’ve found the sentence in teacher-speak for you – ‘bright but wayward’, ‘steady and conformist’ – and they’ll treat you like that for the rest of your time at school, regardless of whether it was appropriate in the first place, of whether you change. It’s a rough and ready institution. Maybe all institutions are. Like being kitted out by a careless and capricious quartermaster. You feel it happening, you know it’s wrong, but there’s nothing you can do about it. You can fight it, you can pretend to be it, you can let yourself become it. But I chose. At seven I chose, and I’m proud of that, even though it was the unplanned act of a thoughtless moment.

I’d noticed Woody at school. You couldn’t miss him; a head taller than anyone his age, thin as a rail, with long blond hair and weird clothes – patchwork trousers, multi-coloured hand-knitted sweaters – more Robin Rainbow than Billy Bluehat. He had an earring! (A stud, actually – earrings were a risk, but girls were allowed studs. And I must say that my mum was one of the strongest in support of him being allowed one – equal rights). Often alone, happiest when putting into practice ideas he suggested to teachers – he made an ingenious device to water the pot plants over the holidays – or drawing them into discussions much beyond his age. Why are books shelved left to right when their pages go right to left? How is it that multiples of nine always add up to nine? If the universe is expanding, what’s it expanding into? (A chilly one, that, to hear when you’re seven; afterwards you lie awake in the middle of the night, hearing for the first time the emptiness of space). He was a loner; not the lonely kid who no-one’ll play with, but aloof, almost disdainful of the other kids – a mocking look as play gradually built to a whole playground thing, we were each gradually drawn in so that at last we were all part of one huge, pulsating entity, himself the only one apart, arms folded, feet set, a half-smile. Usually alone, or with his one special friend of the moment. But sometimes – no-one ever understood how it happened, whether it was spontaneous or carefully planned – he’d gather kids together, the little ones, the misfits, and then, by some sleight of hand (head scratching, how did he do that?) unseat the boss kids from their habitual position on the rubber tyres and substitute his giggling rabble with himself above them all, just as the bell went for the end of break. He was never picked on; there was something about him that deterred it.

Until that day. I was leaving school, a bit late so the lane was empty, apart from, on one side Woody, on the other four boys, tough kids who stuck together. (I’d fought one, got friendly with another). The four were pushing each other around, egging each other on, getting closer to Woody, passing remarks. I couldn’t hear what, but ‘father’ came into it. At first I thought Woody – upright, looking straight ahead – was his usual cool self. Then I saw that he was walking really stiffly, his fists clenched, his face white, barely under control. I’d meant to drop in with the four, show them my new “Star Wars” figure (Luke Skywalker in snow gear, just out, not available locally, quite a coup). Suddenly, as if I was seeing the future, I saw what was about to happen. A kicked stone skidded past Woody, bounced off a lamp post just missing him. Oohs and laughter, and them bunching up. I’d seen a nature film in which a pack of wild dogs – low creatures, each one snarling but timid, crossing and recrossing as if winding each other up, weaving a group courage, getting their blood up until, almost hysterically, they burst out of their self-made space – attacking a lone wildebeest. Of them diving in and tearing and skittering out, of the great creature slowed, stopped, sapped, and at last toppled, its great horned head striking the ground with a mighty thunder, throwing up a cloud of dust. I couldn’t watch any more and had gone out of the room. And now – they’d bait him, draw him in, defeat him. I didn’t even think. (Of such are great decisions made). I drew level, then walked past them. ‘Hey!’ Jason called, in greeting but also in warning. I gave them a cheery wave, but dropped in beside Woody. He spun round, glaring, fists raised. ‘Look,’ I said, showing him the figure, keeping walking. There were mutterings behind, a stone flew into the hedge, they closed, then dropped away. But they stayed around. At the main road I stood with him, talking, until a battered Toyota drew up and a red haired woman leaned over and opened the passenger door, he got in and the car drove off.

After that, things were different at school. I was no longer courted. There was a barely perceptible but very real withdrawing from me. The invisible cordon thrown around Woody was extended to me. I’d made my play.

He came to my house first. All he wanted to do was watch television, eat white bread – ‘can I have some more square toast, please?’ (we always had wholemeal bread, but I asked mum to get white if my friends were coming), and use the bathroom – running off to flush the toilet and wash his hands under a running tap every few minutes, and arranging everything – ornaments on shelves, chairs, place mats – in straight lines. I didn’t understand until I went to his place. In the car, he sat in the front, next to his mum, calling her by name, Celia.

Their place was amazing. It became my second home. Sometimes it felt like my first home, I’d feel miserable when I left, have tantrums. (Mum would say – if it makes you unhappy, perhaps you shouldn’t go there. She meant well but she didn’t understand). That first afternoon I wandered through it in a daze, touching, smelling, feeling.

The only comparable experience, of being sensuously, even sensually overwhelmed, of being so taken out of myself, or plunged into myself that I felt new realms of emotion, was at a great aunt’s house. She was ancient, small and white haired, and mum sat with her drinking tea from china cups, questioning her keenly about her mother (my grandma) as a child. I soon wandered out into the hall, sliding my hand along the dado rail that ran at head height along every wall separating embossed wallpaper below from plain above, smooth, almost plastic with its years’ coats of gloss paint, my fingers exploring, as I walked along, its delicious curves. It led me up the steep, dark stairs (a runner of thin carpet between dark-stained wood) and, following its imagined line across architraves and panelled doors, along the landing. The doors were always tight shut (something I’ve never liked – being shut in, or shut out) and I’d push them quite hard. This day, as I stepped from medallion to medallion on the carpet, head down, concentrating, my hand sliding along – it suddenly gave way. A door not properly latched had given a little. I pushed. It swung slowly back. It was a dark room, heavy drapes drawn half across the window, lace curtain filtering the light. It smelt of mustiness and furniture polish. All the furniture, made of dark wood, matched. Although it was polished, it seemed to absorb the light, each piece a heavy, dark presence. It was very neat – oblongs of carpet on polished linoleum, a bed with a counterpane tucked in so tight it was like carved wood, bedside tables with glass-shaded lamps, a large wardrobe. It smelt of polish and dust. I followed the rail around, away from the bed, over a trunk with foreign labels, to the dressing table. I was surprised (it had three mirrors) by my multiple reflections, saw for the first time – a mirror in a mirror – my face as others saw me, was taken aback by this other, different face. There was a bowl of lavender and a bowl of flower petals. There were bottles and jars, a bowl of powder with a large powder puff, two hairbrushes with handles and silver backs bristled together, a matching hand mirror. I didn’t touch any of these things – they felt naked under my gaze, to touch a violation (as if an alarm would ring, or an unstoppable sequence of events set in train). I didn’t dare open the drawers (how I wanted to!) I passed on, and arrived at the wardrobe. It rose above me, vast as a cliff face. Again, the latch, a curious lift-and-turn affair, wasn’t engaged. I pulled at the edge; the door swung open on squeaking hinges; a figure leapt at me. I dived to the floor, the door swung past then slowly returned bringing with it my reflection again in the long door mirror. High above me, a shelf of hats. Below, in the well, neatly paired shoes. And in front of me, a jungle of hanging clothes, giving off, in this sudden release, waves of different smells – a variety of perfumes, leather, fur, face powder, lavender, camphor. I climbed in, pressing myself between the tightly-packed clothes, light headed with the scents, touching and pressing my face into the textures – fine wool (soft), leather (strong), cotton (smooth), velvet (clinging), silk (slidy), fur (reassuring). I grasped a fur coat, clung to it, buried myself in it. I imagined the satin lining swathing the naked perfumed body of a woman holding me to her. I imagined the fur was a mother bear, large and protective, and me the little bear – as I’d seen in nature films set in the Rockies – trotting along behind her, along a soft path through a flowery, sunlit meadow, beside a rushing, salmon-leaping stream, beneath mountains high and snow-clad…

They found me asleep in the corner, clutching the fur coat, a pair of button bootees over my shoes. I’m sure they didn’t mean to upset me, but the sudden light and noise as clothes were thrust aside, the loud towering silhouetted figures, the grasping hands, the harsh voices, the sudden terrible separation as I was lifted out of the feels and smells… I burst into tears and wept inconsolably.

There were no doors in Woody’s place. I sometimes wonder whether there were any walls. Everywhere there were richly coloured curtains, drapes, hangings. The floors were covered with carpets, rugs, cushions (you always took off your shoes and socks when you went in), I didn’t know what were seats, what were beds, what was floor. There were short-legged tables and large paper-globed lamps hanging low casting strange shadows. There were always candles lit (carefully placed, I realise now, each islanded in water – for all her whacky ways, Celia was very practical). There were wonderful textures under my feet, in my hands, on my face. The air was filled with scents – plants, flowers, spices, herbs, perfume, tobacco, incense. I realised, then, how scentless was my house, how it thereby lacked texture, a dimension. I built a huge soft castle of scented cushions and drapes that I buried myself in, luxuriating in the soft heavy stuff on me, the scented fabric over my face. We ate cross legged from wooden bowls. There was no TV. The toilet was a chemical one outside in a lean-to, and you washed in water from a rain butt. Later things changed. Things were always changing. I liked Woody’s because it was always changing. He liked mine because it never changed. It was all so different. I was in a daze. But what I remember clearest from that first visit, as I lay in blissful contentment, was the sudden irruption into my careful castle, my pasha’s bed, of Celia, tickling, wrestling, laughing. I was annoyed at first at being interrupted, then shocked that a grown-up, a friend’s mother, should behave so. But it was fun, I enjoyed it, the flow of her body inside her clothes and the scents coming off her, and I wanted more.

And how it began was how it went on. Going to Woody’s was like passing through a magic mirror – sometimes it was the most wonderful place, occasionally it was dreadful, but always it was different, always a bit distorted, and sometimes very much so. Always weird, often wonderful.

We would nestle against her, a head on each breast (she never wore a brassiere, and this too I found both disconcerting and pleasurable) as she read to us. Never children’s books but adult literature, with such conviction that we were transported. So we swam with whales in ‘Moby Dick’, flew over star-lit deserts with Saint-Exupery, journeyed through hell and heaven with Dante, sailed in Rimbaud’s drunken boat, lived with bushmen with Van der Post, struck off the Green Knight’s head with a single blow – and watched, as terrified as Gawain, as he picked up his head by the hair and rode off crying ‘keep your bargain, Gawain, come to the Green Chapel in a year and let me do to you as you have done to me’! (She read the original first, and I still remember ‘to fotte such a dint as thou has dalt, to be yederly yolden on New Yeres morn’. [l.252] We were ‘yelderly yoldening’ for days).

She showed us the night sky, pointing out the constellations. I loved Orion, his belt and scabbard, striding across the sky; especially after seeing a shooting star fly from his shoulder as if hurled. She took us out for a lunar eclipse and we saw the shadow of the earth on the moon (a shadow being cast a quarter of a million miles away!) We watched the curved shadow move across then cover the moon, the moon go dim and red, then move off, leaving the full moon bright and clear, cleansed even. (I imagined that shadow, released from the moon’s surface now being carried across space, seeking a surface, any surface, on which to register). Celia stared at the moon with a lost, faraway look on her face. We asked what was the matter. She came to and smiled at us, a deep sad smile, and put her hands on our shoulders and said she was homesick. What did she mean? She said you could be homesick for the place you came from, or for a place you’d visited and could never return to, or for a place you’d dreamed so vividly you were sure you’d been there; and she didn’t know which it was. As we turned to go in, she gave it a little wave. That evening she began telling us the Moon story. She told it, episode by episode, so vividly that it was our favourite story and we’d pester her for the next instalment.

She would teach us whatever she was learning at the time – she was always learning something new. So she’d have us sitting cross-legged staring at the ends of our noses meditating, chanting like Tibetan monks (‘listen to the overtones!’ she’d cry), drumming to the point of exhaustion. While we were estranged, I took to thinking of these as fads, of her as capricious, without staying power. I’ve realised since that they were part of a programme, of which I saw only part, of education, partly for herself but primarily for Woody.

At these times she was the perfect mother. At other times she was unliveable with –she’d become pinched and mean, forbid us things for no reason, attack us, sometimes physically. Woody bore the brunt of this. It was a strange relationship – at times he would look after her, protect her as if she was a wayward child who had to be pacified; at times she’d treat him like a prince to be served; most of the time they shared intuitions, like unusually close siblings.

The situation was complicated by the men. In the middle of their bizarre house I found a minibus. Celia explained with great relish how she and baby Woody had been travelling, ‘just travelling, you know? Looking, following… waiting. Yes, that was it, waiting for it to happen. One night I pulled off into this field. The next morning, the van wouldn’t start. This was where we were meant to be. We’d arrived.’ Simple as that. She charmed the landowner, so confused the planning people that they let her be, and they settled in. From the van at the centre, the home grew, spiralling out like a snail shell. Friends came and built new rooms, greenhouses, composting privies, dug gardens. Men would move in, their skills – this one a carpenter, this one a musician, this one a Zen adept – appropriate to her and Woody’s needs. (Or maybe she was just good at adapting to what came along?) Woody had rough times with some of the men; but if there was a real problem, out they went. Things were always changing – extensions built, demolished, rebuilt differently. The furnishings might change overnight from Oriental opulent to Zen sparse. And what seemed capriciousness or opportunism I later saw was informed by the thread of destiny she believed they were following.

And there I was, part of it all for five years, from seven to thirteen, until I said what I said. I would rack my brains to understand why I said it. Only much later did I understand that, as I got older, I’d been unable to cope with the situation. Because Celia, Woody’s mum, didn’t act like other mums, because there weren’t the conventions, the distance, my love for her, as adolescence approached, had nowhere to go. I loved her passionately. I wanted her. It was impossible. And I got myself out of an impossible situation by having myself banished from her presence, cast out.

It was a phrase I’d heard used, sniggeringly. I hated it. Woody and I were talking about conformity. He was saying that most people conform because they haven’t the courage of their convictions (if they had any), they were cowards, prepared to submerge their individuality in the herd; and that most couples stay together out of comfort not love, fidelity was fear. He sounded so smug and self-satisfied, I wanted to knock him off balance. And I felt he’d been getting at my parents recently and I was fed up, and I thought this too was aimed at them. I said, ‘well at least my mum doesn’t change men like she changes clothes. At least she’s not the town bicycle.’ It was untrue, unforgivable. Shock on his face, then pain, changing quickly (the face, I saw to my horror, that he affected with other people), to stony indifference, an attempt at a sneer. He turned on his heel and walked away, stiff as on that first afternoon five years before.

I thought he’d be back. I thought I’d be back. But, I had other friends and turned to them, and got into a different scene. Woody hung around with older kids. Soon afterwards he began to change radically. Gone were the multi-coloured clothes, replaced by black. He dyed his hair black, had it cut brutally short, with a W shaved into it. A man moved in with Celia who he didn’t get on with and failed to dislodge, and he more or less moved out. He’d doss with friends. Then he moved into a squat. He developed a passion for computers and was soon hacking into the school network, the County network. I hear he’d built up a sophisticated computer set-up at the squat, paid for, I heard, by theft. Now I needed him. He was the only person who could help. And I had to walk into that squat.

Chapter 7

The squat was at the rough end of the Council estate, where broken windows were patched with cardboard, crazed dogs hurled themselves at splintered doors as you passed, gardens looked like bodies had been buried and dug up, raised voices were the small arms fire of domestic war.

The house they’d squatted had been someone’s dream – the dream that he didn’t live on this estate. Done up with hardwood door, leaded windows, a low white fence (plastic) round the scrap of garden; he must have seen it, magnified in his mind’s eye, as if it was South Fork. The house was repossessed, the family put into b & b, and the man had disappeared, maybe to inhabit a new dream; maybe to suffer for the rest of his life, having woken up, for having dreamed. The doors and ground floor windows were nailed up with shuttering ply. I went round the back and knocked on the rough wood that covered the door. I suddenly felt nervous, fearing he’d tell me to piss off, ready to walk away without a second knock, when it opened a crack, a face I recognised from school. He made no sign that he recognised me.

‘So?’

‘I’ve come to see Woody.’

‘Who’s ‘I’?’ I told him. The door closed. I heard noise behind me. Half a dozen kids, seven or eight year olds, with hard, old faces and eyes that didn’t blink, stared over the back fence.

‘Alright?’ I said, friendly. A clod of earth flew close to my head, splashed with a soft thud on the wall.

‘Hey, you little sods, piss off!’ I yelled, making as if to run at them. They were supposed to scamper off in terror. They didn’t move. A second clod was followed by a stone. I backed up against the house, the barrage was intensifying, becoming worrying, when a hand grabbed me and pulled me inside. The missiles drummed, accompanied by yelled obscenities, a meaningless string, a coprolitic necklace, each word as hard as a fist. The battery eased. They whooped off.

‘Tough kids, eh?’ Long hair. Ultra-bright, Upper Sixth. ‘Cross your fingers no-one ever organises them as storm troopers.’

‘Why do they do that?’ I asked. He shrugged:‘They get it from their parents. We’re

different. We show them ways to change their lives but they don’t want to know. They don’t want to change. They were stubborn peasants; now they’re stubborn claimants. They’d rather be trapped, then all they have to do is snarl. When your back’s to the wall, at least you know where you are. The kids have really negative role models. They smashed the wind generator, set their dogs on the hens. Woody’s upstairs.’

On the walls were designs showing the house adapted to save 70% of running costs. Lots of glass. Lots of capital. I passed one room filled with dark, apocalyptic photographs, another with sound equipment and a mixing desk and an impossibly thin, impossibly pale girl who stood, headphones on, her fingers stabbing a keyboard to a rhythm I couldn’t hear.

I stood in the doorway of Woody’s room. He sat immobile, eyes fixed-focussed on the computer screen, face highlit by the flickering data, hands hanging over the keyboard like spiders, then scurrying over the keys like ants. I hardly recognised him. I suddenly realised I hadn’t seen him for months, that he hadn’t been at school, that I hadn’t noticed. He was thinner than ever, painfully thin in the skinny sweater, pale skin drawn tight over the bones of his face, black around his eyes, eyes that shone with a fierce, cold fire, reflecting back the screen, hard. ‘Light’ was razored into the dyed black hair of his right temple. A vein rippled across it like a snake. Alison Duncan – two years older, the impossible dream, light years more mature than we mortals, more mature than we’d ever be, helpless, helpless – watched me steadily from the bed, then uncoiled her slim body and stood in one fluid motion, pulled a long thin hand over her tightly drawn-back black hair, smoothed down her skin tight black one piece, stroked Woody’s hand and whispered in his ear as she passed (he didn’t react), stared hard at me as she left the room – a look that said, mess with Woody and I’ll tear your heart out. And meant it.

Woody stopped typing, said ‘damn’, tapped rapidly again then leaned back, half grimace, half smile. ‘They’ve got a new bloke on the County computer. He’s good. Getting everything bolted and barred. He’s one methodical gate-keeping mother. But he’s beginning to respond. I’m drawing him out. He’s in his castle, see?’ For the first time he looked at me, eyes flinching then recovering as he rolled determinedly on. ‘In his castle, I can’t touch him, so I have to draw him out. I have to work on his vanity.’ He smiled a shark smile.

‘What are you doing?’

‘I’m hacking into every computer system and wiping every reference to this house and its occupants. We’re lasering our tattoos. We’ll become phantoms to them, invisible, unreal because they can’t see us – their computers are their eyes – but in the real world we’ll exist, we’ll be able to do things, we’ll be free.’

‘But why?’

‘Time of change. Next step in our evolution. Unfolding the metagenetic code. Time. And all free, courtesy a home-made blue box, a liberated modem, and some dinky work with crocodile clips on the phone box outside.’

‘But what about the people who have to pay for what you take?’ I said, suddenly prim.

‘Oh come on – what is it compared to fat cat share options and quango sinecures? There’s less and less space, and you have to make your own. Call it “government subsidy”.’ He smiled harshly, looked at me again, fugitive expressions flitting across his face, memories and vulnerability. Silence. I began: ‘I’m sorry about…’

A mask dropped across his face. I could hear the clang. ‘Did you come here to apologise?’ he interrupted. I shook my head. ‘Begin now. Always begin now.’ Like a learned mantra, held out in front of him.

‘I have to get into Jones’s place.’

‘Why – did your ball go over the wall?’ Sneering.

‘This is serious! A man’s life depends on it.’ He leaned back in this chair, hands behind his head. ACCESS DENIED winked at him and he jabbed a key and a screen saver spread slowly across the screen like an opening chrysanthemum.

‘That’s tough one. It’s a fortress – fences, guards, cameras, the lot. I’ve been in for a look-see, to check it out – very hairy. And the computer system’s behind lead. What’s the problem?’

I explained about the old man. As I spoke, heard it out loud, I realised how absurd it sounded – just the ravings of a deluded old man. But Woody took it all in, going to a map on the wall as I talked, a map of the area, with added lines, symbols, geometric shapes, and studied it. When he spoke, it wasn’t to me but to the map, to the denizens of that map.

‘Of course. We always knew the Hall was significant. But we couldn’t figure out what to do when Jones bought it. It was a lock-down. We couldn’t access it. But – maybe the dower house,’ his finger traced over the old man’s house (I hadn’t realised it had once been the dower house to the Hall), its garden, ‘is the key to the Hall,’ his finger tracing similar patterns but on a larger scale over the Hall and its extensive grounds. ‘The key that opens the lock. And the old man’s been sleeping on it all this time, guarding it, and blocking it. And now he’s waking up.’ His hand was roaming rapidly over the map, like a blind man reading braille. ‘“To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven” – and in heaven too. This is big, big, big. It’s the dish, isn’t it?’ he said, turning to me, focussing on me again. ‘We have to silence it.’

‘Silence it?’ I said, suddenly anxious.

‘Not permanently, you understand; just a little – break in service. And I know just the thing.’ He chuckled. Suddenly he was a mischievous kid again. Just for a moment. Then, to me, very serious:

‘But first, you have to do something.’

‘Me? What? Why?’ Alarmed. No, I couldn’t face Celia. He walked over to me, grasped my arm, looked into my eyes: ‘we’re about to do something important, significant. But before we can do it, you need to do something first. In order to move forward, you need to clear something in your past. You told me about it when we first met and ever since its been bugging you, festering in you, growing out of all proportion. A buzzing fly’s become a big dragon. Now’s the time to slay it.’ I saw very clearly, blurted, ‘what, trash Martin’s shop?’ sure, horrified, that he’d been reading my mind that first morning clearing. He smiled enigmatically. Oh he gathered them early, those powers he had later, had been gathering them unconsciously all his life (like all geniuses), was now beginning to work with them consciously. Smiling, he shook his head slowly:

‘Proportion. Take the original offence and respond in kind. No more, no less. This is not revenge; it’s the righting of a wrong. “Revenge is mine, said the Lord” – getting even’s yours. Do you know that “an eye for an eye” was originally a counsel of moderation, an injunction against escalation? Do you know that studies of conflict resolution show that the ideal strategy is to respond exactly in kind, never more? You’re not an avenging angel. You’re not Jesus on Judgment Day. You’re just balancing the books. Make no mistake, it will be painful – we like to nurse our grievances. But each of us must right the wrongs against himself, if it’s at all possible. That way lies liberation. When you’ve done that, we can proceed.’ His face was serious, deadly serious, his words to be heeded. He allowed the silence to grow for a couple of seconds, then he returned abruptly to the computer, typing rapidly, muttering, ‘now, Mister Gate-Keeper, let’s see if we can entice you out of your castle – and slip in behind.’ Alison reappeared, as silently as she’d gone, and gave me a “time-to-go time” look. I went.

I hesitated. I don’t know what he would have done if I’d refused. After all, sorting out the old man was, I now knew, part of his agenda, too. So maybe he was just bluffing. I don’t know to this day. Therein lay, lies, his art. And at first I hesitated. Not just because of my unwillingness to face old Martin – and it was true what he’d said about the perverse pleasure we get from nursing a grievance and doing nothing about it – but also because I felt I was being drawn into something that was getting ever bigger. I felt like I’d stepped onto a roller coaster that was gathering speed, I was balanced on a rock on an avalanche that was heading who knows where. What was I getting drawn into? An old man’s delusion? A drop-out’s self-dramatising theatricals? Other people’s agendas? Maybe I was happy with that, not having one of my own. And, when I listened to my inner voice, I knew that there was something real going on, that I was part of. I felt alive. I decided.

Chapter 8

‘No, Mr Martin, it was definitely 20p. Check in your till – I’ve just got these from the bank,’ I held up the paper roll of new heptagonal coins, ‘and there’s just one gone. I’m sure you’ll find it in there.’

I was exactly his height. I hadn’t noticed that before. Every time I’d come into his shop, from the first time to just now, I’d been small, looking up. Now I was exactly his height. And my eyes were holding his, unwavering. He squinted at me over his glinting glasses. He was puzzled, beginning to be anxious. He looked down into the till. I leaned over. The 20p shone, twinkled, glowed, sang the Hallelujah Chorus.

See?’ I said. ‘Do you want to check the date?’ I added unnecessarily. He stared at it. His bald head glistened with sweat beneath the thin strands of combed-across hair. He fidgeted.

‘I was sure it was a ten you gave me,’ he said quietly, almost to himself. He stared into the till as if a transmutation had taken place within and now, having begun, might not stop. He looked up at me, suddenly stricken, as if meaning was leaking from his world, as if appealing to me to say it wasn’t so. I felt myself grow, fill the shop, look down on him from a great height. Then a light came into his eye. He twigged. He’d been tricked, he knew it, he knew I knew he knew… and there was nothing he could do about it. I returned to normal size, exactly his height. He was almost relieved. He tried to involve me in a conspiratorial look but I refused it; I settled for a shared look of understanding.‘My mistake,’ he said simply, handing me 10p change.

‘That’s okay, Mr Martin – we all make mistakes. ‘Bye,’ and walked out of the shop, stepping lightly, leaving the door bell tinkling and Mr Martin standing stock still behind his counter.

I smiled at the small boy I’d swapped the coins with, bit off the end of the liquorice tube of the sherbet fountain, sucked, and – miracle upon miracle! – it worked. The clean white taste of sherbet puffed into my mouth.

Lifted almost off my feet by the bubble of elation, I walked through town in a daze, the town never having looked so good, to reach the wide green sun-dazzled expanse of Castle Walk, with the emptiness over the open country I needed so the bubble could burst out of me in a mighty ‘Yes!’

I sat on a bench, sucking my sherbet fountain, feeling pretty good.

Chapter 10

Woody was standing in front of the mirror in a tight black outfit like the one Alison had been wearing – maybe the same one, hot thought – applying slashes of greasepaint to his face.

‘Woa, night cricket,’ I laughed. It was the night of the raid, an hour before Woody and I were to go in; plans had been made, back-up briefed (I was amazed at his network of associates, from hunt saboteurs to country gents with occult tastes, via Luddite librarians), the old man – (we knew his name now, Johannes – a lot had happened in the last few days) – ready to operate the ‘neutralizer’ as soon as we silenced the dish; and I was apprehensive, fearful, and nervous as hell. He grunted, finished the exactly-patterned application, nodded, and sat facing me, his expression serious behind the distorting mask. We had to wait for the arranged starting-time, and he ws in story-telling mode:

‘When I was thirteen, I was initiated. The current man had trained as a shaman with the Lakota Sioux. She always chose carefully, my mother, and with my best interests at heart.’ I looked down. ‘We went to West Kennet long barrow. The barrows were places of initiation before they were burial sites. And West Kennet is part of the religious complex that includes the mother figure of Silbury Hill and the dragon figure of Avebury. We, the group of us, built a bender sweat lodge, dug a fire pit for the stones, and sweated. Light-headed from my first sweat, but feeling cleansed, I entered the barrow, naked except for the cape my mother had made for me, and with the small bag of keepsakes from all the women for comfort. Then he blocked the entrance with stone. I was to spend three days and nights alone, in total darkness, without food or water.’

‘That’s barbaric!’ I yelped.

‘Initiation is a transition, from boyhood to manhood. It has to be arduous, extreme, even risky – memorable. Better than in this society with its endlessly drawn-out ‘adolescence’. And during it you receive an incomparable gift – the vision of the totem that will be your life guide.

‘Although my skin was glowing and my head singing from the sweat, there was a dreadful finality as the stone was pushed into place – the scratching sound that suddenly stopped – and I was engulfed in silence and dark. I could see nothing and hear nothing. I tried to pull aside what was obscuring my vision but there was nothing there, tried to open eyes that were already open; I became convinced that I’d gone blind and deaf, that things were happening around me, people in the light, circling, commenting, and me stood, still, head down. I began to panic – the weight of stone around me and above me, the finality… I clutched the bag of keepsakes and shook it to make a sound – such a clamorous noise! – listened to the soft rasp of my bare feet as I walked. I sat cross-legged in the central chamber and meditated, muttering my mantra over and over, clinging to it like a life buoy as I sank… My body ceased to exist – I had thoughts and a wild beating heart but no flesh and bones. My meditation turned to prayer, hardly even a prayer, just cries – help me, please, help me, please. I was abandoned, utterly alone, crying out to someone I didn’t know, who wasn’t even there. I began to cry. I cried and cried – inside me was a black well of tears – all I was was a well from which tears rose up, overflowed, poured out, through my eyes, along my nose, down my face, into my mouth, salty as blood, salt tears dripping, onto my cape, around me, I was awash with bitter tears.

‘How long for? Forever. No time at all. I heard a voice, outside me, inside me, a strange unearthly voice that shivered up my spine, made the hairs at the back of my head bristle. The voice called, I didn’t want to go, I did. I was outside, on a hillside I knew, where we often picnicked, in bright sunshine, the grass brilliant green, splashes of yellow and pink and blue nodding flowers, a breeze soft in my face, patterning the grass; and a small figure, hunched and hairy, beckoning me, sinking into the ground, disappearing. I didn’t want to go underground again, but I had to follow. I walked to the place and there were steps in a spiral anti-clockwise down, I descended into a cavern lit only by the sparkle of jewels and gold, guarded by a dragon with ruby eyes and a smoky mouth. Ahead of me was a small square of light, like a distant window. I knew I had to reach it. I started walking, tripping over bars of gold, stumbling on jewel-encrusted boxes, ignoring them – and the shapes, the things rustling and slithering and flapping around me, against me – smooth skin of snakes and enormous worms, hairy softness of giant rats, the stretched wings of bat’s wings, flashing eyes, sudden open mouths, the stench of bad breath. They were overwhelming me, I was sinking under the weight of their presence, I wanted to roll up in a ball, hide my eyes, surrender. But there was the light, I had to keep my eyes fixed on the light, stumble towards it, lurching over uneven ground, as gradually the slitherings ceased, the ground became level, the window, filled with light, grew to the size of a doorway. I reached it. And found myself, tiny, halfway up a high smooth cliff face, with no way up or down.

‘Before I had time to ponder my situation, I heard a noise; and from the base of the cliff, below me, I saw knights riding out, armour flashing in the sun, surcoats flapping, finely-caparisoned horses snorting and mettlesome, lances high and tied with ladies’ favours and with the pennants cracking in the wind. How fine and proud and purposeful they looked! And how desperately I wanted them to take me with them! I cried out to them from my high, helpless position but none acknowledged me, none turned, they rode steadfastly, staring straight ahead, not speaking, until the last bobbing crest was out of sight, the jangle of equipment and the rumble of hooves had faded into nothingness. I stood, and waited; that was my job. The sun rose in the sky and sank towards evening and was about to set and was filling the world with red light when they began to return, straggling back, in ones and twos on slow, limping horses, their lances low, broken, the favours gone, tattered, wounded, damaged, defeated. They entered the cliff below me as though they were sinking into it, becoming part of it, stone, as if never to emerge. I watched, heart sore. And then, from the dangling bloodstained pennant of the last desolate knight, when he was in the rock and the pennant about to disappear – a red wyvern unhitched itself, flew up, flew up to me and, to my amazement, shock, grasped me in its dragon feet and lifted me off the ledge and flew upwards on powerful beating wings, gyring clockwise up.

‘I alternated between looking up admiringly at its masterful wings, its aspiring head – such noble aspiration! – and staring down in terror at the growing gulf of empty air to the diminishing earth. And then I was hanging, suspended, and the whole earth’s shining orb was beneath me – no longer beneath, before me. And, for an instant, in a flash of seeing – hardly seeing, more knowing – Gaia, the living earth, its rocky bones, its living flesh, the animated circulations of water and living things, the crackle of vitality along energy lines. And man – at once proud inheritor and mean parricide, with his gift, and his burden: choice. And at the moment of realisation, revelation, the wyvern let go. I dropped like a stone. The earth grew. I screamed. I begged for oblivion – the whispering voice, “remember your angelic portion” – I spread my arms, my legs, I opened my eyes and found myself not falling but gliding, sailing like a long-winged albatross, swooping this way and that over the earth, observing good ways and bad, seeing patterns, mapping features, feeling a new certainty, a whole life laid out, and so pleased with myself as I swooped artfully low over the high tree canopy – that I snagged and fell from branch to branch and landed with a thump, the breath knocked out of me.