“The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge.”

A ruined splendour, a white wasteland … what has happened in the great wood?

When his overbearing magnate father dies, Geoffrey believes that he has inherited everything and can at last come into his own. But the old man’s will contains a shock: he has left the estate’s ancient wood, Geoffrey’s secret place, to be “divided equally” between his son and Rolf, a mysterious stranger.

Geoffrey and Rolf meet, divide the wood, and build a fence between them. Each seeks in his half of the wood to realise his deepest dreams: Geoffrey creates at first a realm of solitude, then of culture, finally of spirituality; while Rolf begins from primitive simplicity, evolving his realm into successive expressions of his personality. Different worlds.

But, although separate, their individual paths lead them ineluctably to their interlocked destinies in the ancient wood.

In this tale we share in the making of new worlds, while registering the deep undercurrents of generational and sibling rivalry.

86 pages. Out of print. Full text, 20,000 words, here.

PART I

I

I don’t come here often. But sometimes, when my life has become too complicated, too relative, it’s the only place to be. It doesn’t resolve anything, but it makes things starker, which helps.

My foot on the first cracked tread of the curved staircase, grand, broken.

Do I dare? It has happened so quickly, the building coming apart, as if without Geoffrey, his order, his will, there is nothing to hold it together. Most buildings stand for ages, inertia stronger than disintegration; but here, it’s as if every bond is broken, each element disconnected, withdrawing to its own. I remember being at its deep centre, enclosed within layer upon layer of meaning, letting go, journeying into the unknown, free to be … And I climb slowly, winding up towards the gallery.

I lean over, breasting the emptiness, a bird about to take off, oh freedom! – a sudden vertigo, the mosaic floor lurching up towards me, has me grabbing the thin ebony balustrade. I step back. Then forward again.

Above me the dome of stained glass, ranks of etched geometries, figures, constellations, spiralling up to the rose-cut polar crystal that cracked that night. Life-filled, green-leafed branches thrust between bronze glazing bars. And deep below, seeking roots push into the foundations, through walls, prying blocks apart, reaching towards the empty centre. Tropisms. I push one of the twelve doors, the first, the moon, opal, mirror, spider, madness, love … It sticks, won’t open. ‘Oh, Geoffrey!’ I cry. And although the dome is broken and the painted pillars moss-muffled, his name echoes, visiting each surface in a series of thinning embodiments, then fades to nothing. I walk slowly down the stairs.

At the door I turn, take a last look across the mosaic floor, a graphic encyclopaedia, such learning! to the main room. How often I sat there, how lively the atmosphere, how lifeless now.

Outside, I stand by the rusted sculpture, intertwined figures, lovers: each moved independently, touching, apart, conjunction of two perfect balances in a mutual space; now locked together until structure itself breaks down. I look one way along the exactly-calculated avenue to the solitary tree on the sculpted hill, the other to the jammed wind generator blades, the broken solar panels. I listen to the rippling stream, and miss the hum of the turbine.

‘Dreams are important, aren’t they?’ I’d said. Why had I brought her that day? ‘Without dreams there are no possibilities, only alternatives. To dream you must be a little lost, a little free. And to make a dream come true takes a special sort of courage.’

‘Yes, a foolhardy sort,’ she had said.

‘How so?’

‘By choosing one you exclude all the others. And by making it come true, you bring it into this world, into the realm of your own personality, which is what we seek to escape from in dreams.’

‘I’m impressed.’

‘Don’t patronise.’

It hadn’t worked. Of course it hadn’t. Why had I tried to make this place work for me? Forget her. Forget everyone. Let it be. Let it be. And, yes, to dream one must be a little, unmoored.

I walk carefully through the mazy knot-garden, overgrown now, the rare and precious overwhelmed by the common and vigorous, to the seat in the rose-covered arbour, old, scented roses, pink, sharp-thorned, on the low knoll at its centre. What sensitivities of geomancy went into the locating of this precise place!

From here the whole of Geoffrey’s private domain is in view; and beyond the wood, over the bank, the parkland and the big house small in the distance. My task, as always, is to bring it into being before my eyes, tell its story, then witness it falling apart. As if with this telling, I will understand. I close my eyes. Opening my eyes, I examine carefully the scene before me, and at last bring my eye to rest on the distant golden house that, in this instant, is lit up, illuminated by a beam of soft silver light.

Geoffrey’s story

There was once a man who began his life very poor, and ended it very rich. He had a genius for making money, a genius whose origin lay in a singular view of the world; he saw everything in terms of price: what price to pay, what price to sell at, what price this man will take, that man will give. The world as market, its fuel financial transactions. Throughout his life, from selling single cigarettes and matches to school mates, to selling fleets of warships to governments, he applied the same principles: no ethics, beyond the basics required to stay in the market, with need measured by the willingness, right by the ability, to pay; associates are safer than friends, and the safest associates are the most dependent; trying to be liked and avoiding being disliked waste energy and get in the way of business. He did not lust after money; his pleasure was in making good deals. And the best deals were those that made the most money. To that end he got up before the other man, went to bed after him, and worked harder in between. And he became extremely rich.

Of course such an obsessive life had corollaries: how can you simply look at a Bellini “Madonna”, value it, when you are thinking of the price you paid, the rivals you beat, the amount its price has risen? where is there a place for a companionable social life? how can there be friendship where everyone has his price?

The middle-class wife was sidelined when he no longer needed her modest capital as seed corn, succeeded by a steady parade of attractive, expensive twenty-two-year-olds. All that went on in London, the Côte d’Azur, the Caribbean. A simulacrum of family life was created at the big house in front of me, rebuilt in the Eighteenth century on West Indian sugar, set in a landscape remodelled by Lancelot Brown, surrounded by farms bought cheap by the then owner, an armaments manufacturer who’d bought his Barony from Lloyd George, during the Depression. It was furnished and decorated with the finest things, on the advice of experts who knew what was going up. The result was a house full of quality but without class.

It was there that his wife and their only child, Geoffrey, lived, and where he came when required by obligation or the sudden, infrequent surges of guilt.

Geoffrey was expensively educated, given all the opportunities his father had never had. His mother, a timid, dreamy woman whose limited self-esteem had been ground to nothing by the rich man’s abrasive ways, could offer him little beyond sentimental love and a narrow, grey orderliness. His father would alternately take him up, whisking him away to exotic locations for glitzy holidays, insisting he lose his virginity with his own mistress (the next day she was gone, never seen again), having him spend days in his office, the humming, phone-yelling centre of his empire, the glass-walled powerhouse high over silent London, the highest in the land, aeroplanes passing silently, grooming him for the succession; and ignore him, not be in touch, fail to return his calls, as if he didn’t exist.

For the rich man could not accept his own mortality. And he could not forgive Geoffrey for being a reminder of that mortality. For years Geoffrey thought that his father would will himself to outlive him. So that when the old man died, Geoffrey’s strongest feeling was one of relief. ‘Now,’ he said as he watched his father’s desk being moved out and his own moved in, ‘now my life can begin.’

The old man’s will contained one surprise, and it concerned this wood; it said that the wood must remain unaltered until the old man’s intentions were revealed, in a codicil to be opened three years after his death.

Geoffrey gave this little thought. He was fully occupied holding the business together in the period of uncertainty and instability that follows an entrepreneurial buccaneer’s death. He moved quickly to consolidate the core business, off-load the riskier parts, put into place a solid, conventional corporate structure. His time at Business School paid off; the market responded, giving the revamped company a “dependable” rating.

He then focussed on improving the corporate image, with carefully-placed sponsorship, an annual “Environmental Action” prize, research endowments carrying the company name. He was soon two rungs up the ladder of the great and the good.

He got married and started a family. He had met his future wife at his father’s funeral, found himself impulsively thrusting a handful of earth into her hand to throw onto the lowered coffin. They made love that afternoon in the old man’s office, she on top, he staring up at his father’s portrait, thinking, there you are, you old bastard, cold in your grave, while I’m here, now, so bloody alive, a sudden rush of heat in his belly when he came, as if she had impregnated him, crying tears of gratitude and relief, holding her close.

She was a warm and cultured woman, the sort his mother might have been if given the chance. Under her careful supervision the house became a stylish and comfortable place, noisy with children, busy with guests, alive with social occasions. Geoffrey began to feel, at last, solid, located.

But as the time drew near for the opening of the codicil, his thoughts cut loose ever more often from the formal complexities of business, to imaginative speculations on his father’s intentions He found his eye straying from the refined comfort of the drawing room, through the French windows, across the parterre and sunken fence and up the carefully-casual parkland, to the furthest corner of his domain, the wood. Sometimes he imagined a sudden leap to a new freedom as his father, dead, was able, in that codicil, to say at last the words he had never been able to say living. And sometimes he saw descending on his briefly unencumbered shoulder a hand that would never be lifted.

The day before the third anniversary of his father’s death, Geoffrey stood at the edge of the wood, wearing new boots and walking gear, and carrying a stout stick. He had never entered the wood: his nervous mother had discouraged him from wandering alone on the estate, had emphasised the dangers of the wood; and he had been an obedient boy. He took a deep breath, climbed the bank, crossed the ditch, and confronted the wood.

A chaos, a tangle of trees and undergrowth, vertical pillars locked together by diagonals of fallen trees and broken limbs, palisades of slender trunks, entanglements of bramble and thorn. He launched himself in, slashing with his stick, tugging his thornproof clothing free, kicking through the underwood, cursing as first a hazel then a briar whipped his face, aiming for the centre, bulldozing on, aware only of his slashing progress. After several minutes battling he emerged suddenly into a small clearing and, breathing hard, stopped.

There was soft grass underfoot, and trees all around, tall smooth slender trees reaching high, reaching for the light with bright leaves, exactly outlined emerald shapes shimmering against the blue sky. As his breathing quietened he began to hear birds, for the first time, each a short outpouring of song followed by silence, each an individual spark of livingness, each exactly located although invisible, giving him through the ear a sense of depth and distance denied the eye by the density of vegetation. And with each birdsong came a faint echo, and a sense of their and his enclosure within the same space. The aural clue to the spatial dimension awakened his eye to more than the immediate, to see direction, to begin picking out faint paths through the wood. He followed the paths, at first changing direction towards the imagined centre, but soon acknowledged that he was quite lost, and then he simply walked, at the centre of his own small circle of experience.

Within this small compass, his eye cleared. He could stop and simply look. Lichen on a rock, a fragment of it suddenly unpeeling, fluttering through the still air, landing on a tree limb, becoming part of it, gone. Two slender trunks twisted together like enraptured lovers. A tree so fair of line, so full of form that he loved it. An antlered stag in a sunbeam, staring full face at him, then snorting and crashing away through the undergrowth, leaving a swirl of animal energy that he felt enter him.

And then he came to the tree. His search for the centre of the wood was forgotten; he had arrived at his destination. this moment’s centre of the world. An enormous beech, lofty and spreading, strong of grey limb and firmly rooted. He entered its protection. He leaned back against it, felt its sap, the sanctuary of its branches and foliage, closed his eyes; felt it send him forth strengthened.

He walked on, quite lost, not caring, entirely self-possessed. And suddenly was at the wood’s edge, and before him was the broad prospect, the distant horizon, the vast sky, and around him a great width of air. He gasped, suddenly breathless. Then his eye focussed slowly on the warm solid rectilinear house, and he set off across the grazed grass, staff swinging, looking all around, feeling the wonderful expansion after the tight wood. He looked up, and stopped. There, in the slow convolutions of cloud he saw his father’s face as he had never seen him; open, benign, unenvious, pleased for his son having experienced something he had not. In the moment he stared the clouds tumbled the face out of existence, but it had been there, he had seen it, and he threw his staff high into the air, watched it spin upwards, stop, tumble down; and he caught it.

The face was still clear in his mind when he took his seat in the solicitor’s office. The solicitor opened the envelope and read:

‘“I leave Gore Wood to my son Geoffrey, and to Rolf Marten, the two to meet together, alone, thirty days from this date, at the wood, there to divide the said wood between them, as they agree, their decision on that day to be final.”’

‘I don’t understand,’ Geoffrey said.

‘That is all I have – together with some instructions as to how to locate Mr. Marten.’

‘But who…?’

‘I know no more.’

The face faded, was gone. The space it had occupied within him contracted, closing, closed. In its place a small patch, quite dead of feeling. He left quickly, was already punching buttons on his phone by the time he reached the held-open door of the limousine, busyness his habitual response to emptiness and confusion.

To no avail. He, for whom knowledge was meaning, meaning was power, with his researchers and information services, could find out nothing of use. He needed something to bring to life that small blank patch, but he could not find it, not about the wood, not about Rolf Marten. The more information he gathered, the more helpless he felt, for he didn’t have a clue.

At the appointed time Geoffrey approached the meeting place, his head filled with chattering facts.

Suddenly, when he saw Rolf, it was as if the facts he had gathered were printed on the outside of a flat balloon, a balloon that was inflating inside him, and that he was now inside, inside a bubble of expanding emptiness. In front of him was a man he was seeing for the first time, isolated in the same emptiness as himself – the balloon enclosing them and the space between and around them – who was at that moment more real to him than anyone he had ever seen … How to explain?

An only child grows up in a world of whole numbers, of discrete entities. There’s none of the relativity of being a later child, the displacement at a subsequent birth, none of the being part of the changing pattern of relationships with parents and siblings, none of the bequeathing, the inheriting, the sharing of clothes or toys, that loosening of identities that comes when people mix up your names, or describe you as X’s brother, compare you with a sibling. There is a father, a mother, a child, and you are singular, an entity, occupying your own space.

But now, in his wood, his space, walking towards him in perfect step, was the one his father had chosen to share that space. He saw only Rolf.

At first, as they moved in exactly the same way, he saw a mirror image of himself, someone quite different who yet occupied the same space, moving steadily, as in a dream, towards him. But then, as they closed, he felt as if the space he occupied was being invaded; he felt hot, breathless. And then suddenly he was filled with an uprushing emotion, stronger than any he’d ever felt before, a desire at the same time to fall upon this intruder and destroy him, and embrace him, melt into him, become one … Their eyes, Geoffrey’s cool grey, Rolf’s intense blue, touched, flashed lightning between them. They looked away. Never to look again. The eyes of each roamed neutrally over the face of the other as they stood close. Then each extended a hand across the space, met at the mirror, grasped, let go, the hands fell back, each on his own side.

The bubble was gone, and the birds were making a terrific din. Geoffrey fumbled through his thick file of notes while Rolf looked relaxedly around.

‘It’s a fine wood,’ Rolf said in a soft, nondescript voice. Geoffrey didn’t respond, studied his notes then looked up abruptly and said:

‘I don’t know whether you’ve studied it?’ Geoffrey had, every leaf and stone. ‘I jotted down a few ways of dividing it that seem equitable,’ each division favouring, just a little, himself. ‘It depends on what you want to do with your half …?’

‘I haven’t a clue. I haven’t the least idea. I’ve never owned a square inch of land in my life, and I’ve no desire to now. But I suppose if it’s someone’s dying wish that you have something, it’s only respectful to accept it.’ Looking around, then back at Geoffrey, with a smile said:

‘Tell you what – you take the half you want, I’ll have the rest.’ A suggestion that somehow felt like a challenge.

‘That hardly seems fair.’

‘If we both agree, it’s fair – isn’t it?’

‘This one, then.’ The best land, the finest trees for himself, the more isolated, lower, sandier places for Rolf.

‘Great. See you.’ They both knew they never would.

‘Oh, just one more thing,’ Geoffrey said, ‘you wouldn’t consider selling your half, would you? I’d offer a very good price.’

‘Not for all the gold in Fort Knox,’ Rolf smiled.

Geoffrey returned to yet more study of the wood, fearing a trick, that he’d missed something. He could find nothing.

It was an ancient wood, part of the original forest, enclosed in Anglo-Saxon times and thereafter managed in a typical way, coppicing for wood, standards for timber, for a thousand years.

In the 1780s the owner’s sensibilities, awakened on the Grand Tour and refined by his studies of the ‘Natural’ landscape school, were so offended by seeing the village (which of course long predated his house) between the house and the wood that he had a new model-village built out of sight beyond the wood, the old village razed, and the area landscaped as parkland. He also planted colourful exotics among the native species at the edge of the wood to improve the colour harmonies of the view from the house.

In the nineteenth century, the heavy hands of gangs of gamekeepers, brought in to retain the wood as the owner’s preserve led to pitched battles with the locals, harsh punishment, dark, sullen resentment.

In the 1940s an area of conifers was planted, but never harvested.

Studies of records, maps, and on the ground, with metal detectors, potentiometers, divining rods, revealed a great deal – an iron-age burial, lime kilns, charcoal pits, an iron-making furnace, saw pits, a rabbit warren – but nothing of significance or value. After a week Geoffrey was certain there was nothing special about the place.

He spent another week pondering the significance of Rolf, replaying his memories of their short meeting.

He was obsessed by the figure of the man, kept seeing him enter that common space, a red figure in the blue. Red-haired, red-bearded, a scarlet thread around his wrist, walking exactly like himself, and yet quite different. At ease. In possession, not of the place, but of himself. At home in the space he occupied. He had made Geoffrey feel muffled and confused. But still the sense of something in common. The red hair – was this Esau, the elder brother dispossessed by the younger? The scarlet thread – was that Zarah, who put his arm first from the womb but was preceded in birth by his twin? ‘Is this man, then, my brother?’ Again the contradictory desires: to draw him in, to admire him and put himself in his hands; and to eject him, to lock him out. And didn’t, anyway, Cain and Ishmael and Esau represent the line of nature, and Abel and Isaac and Jacob the line of grace, those with God’s ear? ‘I am the chosen one,’ he said with finality. ‘Rolf is a test. To allow him in would be to put at risk all I have created. He is the temptation to be resisted.’

The next day he caused to be erected a high and secure fence through the wood, on the agreed boundary. Satisfied, Geoffrey turned away from the wood, and forgot about it.

III

Years passed. Geoffrey was too busy, became weary, his life circumscribed, taken up, with nothing fresh in it. He dreamed of escape, saw the futility of that; he needed not an escape from his life but something new at its centre.

It was quite by chance – or so it seemed at the time, only later realising how inevitable it was – that he found himself one day, wife and child away for a week and he becoming more and more silent, alone, disconnecting himself in a way he hadn’t done for years, standing at the edge of the wood. He remembered, not the last time, the meeting with Rolf, but the first time, and the face in the sky. He entered, sought out the great beech, lay himself between two giant roots, as in a crib, and slept.

He had found his place, the place where he could be alone, the place where he could dream.

Sometimes he would tramp for hours, in a labyrinth, round and round, this way and that, following a clue. Sometimes he would simply sit, in rapt contemplation, with more space inside him than he had ever thought possible. His wife, a wise woman, understood, was not jealous. And Geoffrey would return to the big house refreshed.

After a couple of soakings, he had a small summerhouse built.

Occasionally he would stay overnight, enjoying the way the wood settled down as it grew dark, as it gradually drew the night around itself; the night, with familiar beings sleeping and other, strange creatures, quite different, stirring into life, and the stars in a black sky; and the coming of dawn, from the first exact, realised song and touch of light, through to the full ecstatic livingness of day.

He began to imagine a real house in the wood, something entirely his own, an expression of himself, a confirmation.

Perhaps a mediaeval keep, built of dark stone, ivy-covered, with with a moat and drawbridge, lancet windows, and a circular staircase winding down into the depths and spiralling up to a high-reaching tower.

Or a Modernist master-work, all horizontals, split levels and glass, proportioned to the golden mean, cantilevered out over a waterfall, built around a great tree growing up through the middle, and with a Japanese garden of raked gravel and rocks.

Maybe a house of glass in the form of a regular solid, that in some lights would disappear entirely and at other times would glow like an enormous cut jewel.

A woodcutter’s cottage, with a twisted chimney and mossy shingles, and hollyhocks and roses to the eaves, that deer and witches would visit.

Or a log cabin at the edge of the known world, at the beginning of the ancient, endless forest, Hercynia, from which he, the first settler, could ponder the forest ways and, rather than plotting its destruction, gradually learn to enter and live within those ways.

So many possibilities. An enjoyable game. And a pleasant surprise for him to find his imagination so freed.

But a game. For at quiet times, when the chatter of imagination stilled, and he felt as if his body was dissolving from around him so that he became perception, a neutral I, then he knew that what he wanted was a house entirely without references, that represented what the wood was to him: solitude and independence.

So he had an autonomous house built. With its cellar of rocks, its variable-angle wall of triple-glazing, automatic louvres and blinds, insulation, heat pump, wind generator, water turbine, methane digester, wood-burning stove, banks of batteries, it was the finest, most complete example in the country.

Through it, he grew closer to the wood.

For although the house was autonomous in relation to the outside world, it resonated like a tuning fork to its precise environment. He became ever more attuned to both the generalities and the nuances of natural forces: the temperature of the water flowing through the solar panels, the strength and direction of the wind, the life of trees as he learned to manage the wood, the earth when he made a small garden. When the wind blew he imagined where it came from, pictured energy winding into the batteries as vividly as a key tightening a spring. When it rained he felt the earth absorbing the water, knew that exactly two hours later the stream would fill and the turbine spin faster.

At work he was a node in a network, a point located and defined by numerous strands of relationship, fastened into a global web that never slept but whose activity rose and fell like a tide with the passing sun, a decision-maker among uncountable decision-makers, a player among many players. And in his family he had a role, an ascribed status, a given place. He resented neither of these situations. But neither gave him what the wood gave him.

Alone in the wood, how he lived was determined by local geography, micro-climate – rain a mile away didn’t nourish his plants; and each of his actions had consequences that bore directly upon him – for if the axe slipped, it was his finger that was cut. He began to feel, for the first time, the outlines of his own being. It worked well, this careful, autonomous solitude at the centre of a busy life. And then he saw the girl.

At first a glimpse so fleeting that he wasn’t sure he had seen a face or not.

The second time she confronted him on the path, legs apart, arms akimbo, staring defiantly at him – and then, before he recovered from the shock, skipped away, moving quickly, like a forest creature along secret, familiar paths, swallowed up first by greenery then by silence. It left him angry at the intrusion, furious at her flight, swishing at the vegetation with his heavy stick and shouting, in impotent rage: ‘Hey! Come back! Come here this instant! This is private! You have no right! This is mine! Do you hear? This is mine!’ His voice echoed in the silence, and then there was nothing; until, as he listened, he heard the sound of a distant motorbike being kicked into life.

He could not get her out of his mind. Crotch-tight jeans, heavy boots, knotted blouse, the stance of one who doesn’t give ground easily, a red mouth that had tasted much, maybe too much, but tasted, eyes without fear. The following week he expected her, waited for her. She did not appear. Nor the week after. Was it because he’d shouted? Hardly. Maybe he had been a game she had tired of.

He was forgetting her, having placed her in that sad, tender place we reserve for ‘might have beens’, when, thinking about his tomatoes, he strode round a bend in one of his favourite paths, and walked into her hanging body, setting it swinging from the creaking rope.

The rope tight round her neck, head askew, face bright red, tongue lolling, eyes staring. She swung slowly, heavily. He stepped back, reached forward, stopped, stared, whispered, ‘No. Please. No.’ He wanted to fall to his knees and beg. The top button of her jeans was undone on the roundness of her belly, her navel. Urine darkened the denim.

And then, with a sudden agile movement she unclipped the harness, landed lightly at his feet and with a leap cartwheeled away crying, ‘I’m alive! I’m alive! Catch me if you can!’ and was gone.

He crashed about in the undergrowth for a long time, completely upset; thrown by how deeply he had felt when he thought her dead, angry at having had his emotions so manipulated.

At first she was nowhere. Then he glimpsed her in the distance. And, as his anger faded she came nearer, so that when his anger was gone and there remained just a crystallized residue of resentment, she was walking parallel to him, keeping pace, a little distant.

At first he ignored her. Then he looked at her reproachfully, said, ‘how could you?’ They came to a clearing. She stopped, and so did he.

‘Have you never wanted to do that?’ she said fiercely. ‘Put your head through a noose, jump, feel it tightening, your life being squeezed … out.’

‘Don’t!’ he cried, then quickly, confessionally, ‘I sometimes imagine – ceasing to be. That it would be simpler, just not being.’

‘No, no,’ she snorted, ‘doing yourself in, snapping the spring, leaving an empty body, swinging.’ Silence. Then a single bird call, brief. She sat on a fallen tree trunk and so did he, a person’s width away.

‘When it happened,’ her voice low and intense, ‘I wanted to kill him. I wanted to throttle him. I tried it on myself, gripped my throat, pressed my thumbs into my windpipe. I tried to kill myself imagining I was killing him. I went unconscious. Then I woke up. It’s not easy, killing yourself. I carried on living. I couldn’t read – the words made no sense. I’d stop on the steps of my favourite art gallery and turn and walk away, helpless. Trashy songs’d have me bellowing. I’d been a fool, a fish swimming around looking for a hook, thinking – I don’t know, hadn’t thought at all, just dreamed. It wasn’t like a dream. It was like swallowing molten metal. I played the Liebestod again and again, again and again, until the groove was worn smooth and there was just a hiss and I was like that groove … I didn’t flinch. I’m alright now.’ She smiled, her face radiant and empty. He felt his resentment dissolve. He felt some of the magnificent radiance, the terrible emptiness. They sat for a long time in silence. They watched a heap of earth grow at their feet, a mole appear, peer blindly around, then dig straight back down. And then she left.

He watched her go, head back, hair swinging, defiant and graceful. When she had gone, he felt her absence, realised that something had changed, that the wood was no longer his alone. And that he didn’t mind.

Sometimes he prepared an elaborate picnic, laid it out in a dappled place on a white lawn cloth, bowls of salad, hot bread wrapped in cloths, dishes of fruit, fine cheeses, cooled green bottles beaded with condensation, and dozens of flickering candles, sat beside it for hours, watched the candles burn down, go out, and she didn’t come.

Sometimes he awoke very early, the sun just up, quite empty, a vacuity defined by the world around him, contentedly empty; and then, opening his eyes, see a single flower in a thin vase, that she had placed while he slept, that entered the emptiness, glowed there living and immaculate, and his eyes closed around the flower in emptiness.

Sometimes they walked through the mist for hours in silence. Sometimes they talked non-stop through a whole day as the rain dashed in flurries against the glass, ran in rivers outside.

‘Why do you come here?’ she asked.

‘To be free.’

‘Of or for?’

‘Sorry?’

‘To be free of something or for something?’

‘I’ve never drawn the distinction. I lead a very busy life, I have many obligations, I’m tied into many systems that involve me in the past and the future, in a dozen places; I live my life in fragments. Here I can just be myself, now.’

‘Of,’ she said dismissively.

One heavy summer afternoon, with sky of light-absorbing brass, and air like glue in which a bee buzzed fitfully as if trapped, and the distant rattling harvester chopped meaninglessness smaller, he was lying sweating in his hammock, where he’d thrown himself like a sack of cement, when she approached silently and handed him two postcards and left.

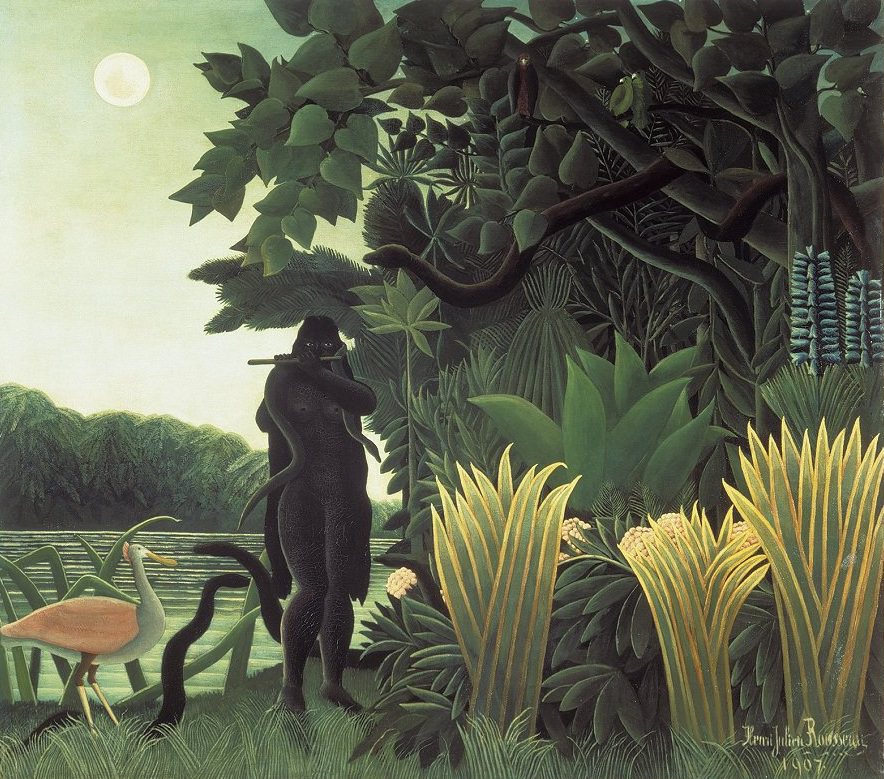

One was a reproduction of Douanier Rousseau’s The Snake Charmer.

This poem, by was written on the other:

IN TIME LIKE GLASS

In Time like glass the stars are set,

And seeming-fluttering butterflies

Are fixèd fast in Time’s glass net

With mountains and with maids’ bright eyes.

Above the cold Cordilleras hung

The wingèd eagle and the Moon:

The gold, snow-throated orchid sprung

From gloom where peers the dark baboon:

The Himalayas’ white, rapt brows;

The jewel-eyed bear that threads their caves;

The lush plains’ lowing herds of cows;

That Shadow entering human graves:

All these like stars in Time are set,

They vanish but can never pass;

The sun that with them fades is yet

Fast-fixed as them in Time like glass.

He read it, then looked around, listened, astonished. He studied the picture, the dark foliage, the darker figure, the strange bird, the moon-touched water. Again he looked and listened. The words, the picture were outside him. But now they were inside him too. A poem and a painting that had not existed to him a minute ago were now part of him. And they were part of this day. For instead of haze and heat and torpor inhabiting him entirely, they were now outside; and inside were the coolness, the stillness, the clarity of the poem, the darkness, the mystery, the ghostliness of the painting. And in their meeting he felt confusion; but enlivenment too.

One late summer day he was sitting facing the great south window, watching clouds roll endlessly in feeling, it seemed, the soft, fresh wind in his face, listening to the hush of rain onto leaves, the trickle of water as it gathered into rivulets, seeing the changing shapes in the sky, the brightening and dimming of the light.

She came in quietly behind him. He did not turn. He heard her moving around, shifting furniture for quite a long time, then she was silent. When he was ready, he turned round. She had gone.

The room was transformed. There were new, brightly-coloured hangings. There was a drape of rust-coloured velvet flowing down one side from a high shelf, on the other a tall painted paper screen diffusing the light. Between them was a low table.

And on the table was a small bronze figure of a galloping horse, a flying horse, three legs stretched out in flight, the fourth touching a swallow’s back; the head of the flying swallow was turned as if in surprise at the sudden, light touch, and the horse seemed to whinny and shy at the contact. Two flying creatures touching. A moment carried over two thousand years. When he looked away, the horse flew on, the swallow swooped away; when he looked back, there they were, touching for eternity, and his eye could savour the detail of nostril and mane and flying tail, and the way the piece exactly occupied its place.

Outside the rain and the storm that would soon blow over; inside the beginning, he knew as he looked at what she’d done, of a rich harmony: at the centre, a miracle of art that was like an exposed beating heart. His.

‘Damn you,’ he said quietly, fiercely; then ran from the house, shouting through the wind and the rain:

‘Okay, you win, we’ll do it – WE’LL DO IT!’ He ran around like a mad thing, slapping through wet branches, sliding in mud, hurling rocks into the turbulent stream, punching at the churning sky. At last he threw himself down on his back, out of breath, arms and legs stretched, the rain pelting his face, whispering, ‘we’ll do it.’

IV

So ended his privacy, his self-sufficiency. And so began his education in that intensifying artifice, that lie that is said to lead to truth, called Art. Not as a practitioner: he already knew that in this individualistic age it is easy as never before for the untalented to ‘express themselves’, to be ‘creative’, that far rarer than the mediocre is the good artist. What he learned now was that, rarer indeed than the good artist, is the individual who not only appreciates art, but also supports it. Not the consumer, who pays his tenner and enjoys it, more or less. Not the collector, who isolates the work, tries by owning to possess it. But the patron: who trusts the artist (having trusted himself to recognise the good artist), believes in him even when he doesn’t fully understand (doesn’t expect to) and, by his commissions and subventions, enables the artist to have the necessary degree of freedom to work (that degree varying, crucially, with each artist).

She taught him well, developed his given good taste, through discussion, demonstration, example. And she knew many artists, especially the unusual, the unfashionable, the unhurried ploughers of solitary furrows though they plough to kingdom come.

The isolation of the place was ended, the solitude gone; but he did not miss it, for his life was more than commensurately enriched.

The garden was laid out by a geomancer with knowledge of pagan and oriental geometries, and filled with plants by one gardener with a rare eye for form and colour, another with the healer’s art.

A gallery and concert room, all tension wires and aluminium, was built by a yacht designer.

The autonomous house was remodelled, there was new furniture, paintings, sculpture.

There were gatherings, discussions, concerts, events.

The place hummed with energy and vitality.

I asked him once why he had done it, why he’d given up the one thing he had here that he could have nowhere else.

We were standing at dusk – the wood dark, the sky still full of light – on the fretted bridge over the stream, bathed in evening scents, looking across a garden of sun and moon flowers as big as plates, to the illuminated house, floating in its own reflection, paintings as bright as children’s, sculptures dark as absence, to the still figures in thrall to the eerie liquid sounds being brought forth from the electric oud by the intense, robed Moroccan. The birds stopped singing one by one. A white owl flapped noiselessly across. He smiled, that relaxed, almost dreamy smile that I saw on his face only at this period in his life, a smile of contentment.

‘I love the juxtapositions,’ he said. ‘Look at all this – isn’t this, what is arranged here, the glory of man? I love the refining, the intensification – higher, deeper, call it what you will. It’s only in art, nowhere else.

‘And being wealthy, you see … I’d wanted to escape, ‘be myself’. But if you’re wealthy, you can’t be yourself. Your obligations are as great as your wealth. You may use your wealth to evade your obligations, as Fotheringham did when he moved the village out of his sight and closed off the wood, or to fulfil them. Here, this, is one way.

‘And, in compensation, there are moments when obligation and fulfilment balance each other exactly; then there is a nullity, a point of rest, a stillness that is quite perfect.’

He was the best patron of his generation, the catalyst for the new vigour and vitality in the arts that we’re still benefitting from today. He knew it, and felt good about it. And the girl, of course.

One day she left.

They were never lovers, but they were partners, two halves briefly one. She often said that one day she would go, and he lived with that knowledge; and one day she wasn’t there, and he knew, at once.

At first he carried on. But the spark was gone, nothing ignited anymore, it was all running down. He stopped the weekends, then the commissions. He endowed a foundation to finance the sort of work that he’d supported here, but he had nothing to do with its running. Eventually he stopped coming here, worked harder, spent more time with his family, and this place lay abandoned.

One day, for no reason he was aware of, he came back. He wandered through the dusty silence, looking at the beautiful objects, remembering back through things that had happened here. He remembered the Chinese horse. He remembered her hanging, imagined it ending there. He remembered the period of his solitude. He remembered climbing up the bank, seeing the wood for the first time, entering it. He remembered how the wood had felt when it lay on the other side of the bank. He cursed the girl for what she had encouraged him to do, his father for what he had led him to do. He cursed himself for what he had done, for having entered, for not having let it be. He wished for that time, that space not to have been defiled. He wanted to destroy it all, to remove every trace of his having been here, for the wood to be as it was.

But he knew it could not be, that to destroy it wouldn’t erase it, but be simply yet another act of despoliation. Wanting to act, unable to do anything, helpless, paralysed.

He found the drinks cabinet untouched, made a circle of the bottles, and got very drunk: angry drunk, depressed drunk, sentimental drunk, and finally energetic drunk, on fire with bright, clear, impossible purpose. He staggered around the house moving furniture, shifting objects, changing everything around, upsetting the given patterns and thus erasing associations, creating something that he knew, with blundering certainty, made sense. Then he collapsed on the floor and slept.

When he woke he couldn’t move. He felt as if he was nailed to the floor. When he began to shift, he felt vertigo and fear, had to return exactly to where he had been. The only movement possible was to make himself smaller, to draw his limbs in, to roll into a tight ball. His head ached. He looked around, in the end-of-night grey light. Everything looked different. It was different. Unfamiliar, and yet having the memory (or was it the premonition?) of familiarity, illusory, but possible.

He sat, egg-like, arms around his shins, and waited. He didn’t know what for, but he had to wait.

At last from behind the hill on which the single tree stands, the sun began to rise. Molten, gold and vast, at first silhouetting the tree, then consuming it, in its light, its fire. A moment of radiance, and then his eyes were stabbed blind. He closed his lids on a single, enormous, all-consuming image. It was an hour before he saw again, an hour in which, sat on that spot, blind, the revelation burned deep into him.

He told me about it, eyes shining with belief:

‘I had collapsed, you see – accidentally? inevitably? who knows! – at the centre of the house, the null point at which all the energies of all the objects, all histories and futures, exactly balanced. And from that point, a place without characteristics, colour or strain, I, neutral and empty, could look out.

‘I saw, in my mind’s eye, the sun, and I saw the tree. The trunk, singular and upright. The spreading roots anchoring it immovably to the earth, drawn down by the attraction of the earth, drawing up nourishment from the dark. The spreading branches, exact mirror image, drawn to the light, reaching to the sky, absorbing the sun’s energy. I could feel the roots blindly nosing through dark, thick soil, touching, tasting, seeking. I could feel the trunk, firm and yet yielding, solid and yet an ever-open channel of ascending and descending. I could feel the branches moved by the wind, the leaves spreading to the light, breathing, giving and receiving.

‘This, this place, centred on this very spot, would be my tree. For I had experienced, in a personal revelation, as I discovered in subsequent studies, the universal religious tree. The Jewish Sephiroth, the Norse Yggdrasil, the Buddha’s bo tree, the Quabbalistic creation tree … And that tree, at first clarified and silhouetted by the sun, and then overwhelmed and consumed by that blinding One that lies before, behind, within, beyond …

‘In this age, you see, each of us must experience his own revelation, then create his own religious expression, to register in this fragmented world his oneness with the One.’

And so he created the last house.

He had a chamber made under the centre point, a sphere lined with soft materials, unlit, the place of initiation.

The chamber and the ground level were connected by two spiral staircases, one clockwise, one widdershins, a helical pair to climb and descend in different rites.

At ground level he caused to be created and laid out the field, a vast mosaic depicting the experiential world, of rocks, cities, plants, arts, symbols, artefacts.

From it rose the staircase, a logarithmic spiral up to the gallery of experience, with the twelve rooms of action, experiment and learning.

Over all was the dome of devotion, its etched and coloured images, ever-changing, objects of, subjects for, contemplation.

And at the pole of the dome, the crystal of revelation.

His own church, his own religion.

Or, rather, his distillation and exemplification of, the religious.

It was a place of activity and colour, beauty and joy, a meeting place for those of many faiths and beliefs, and none, each finding their own truth in what Geoffrey had made. For, although he studied extensively, sought help and information from experts, drew ideas and images from many religions and beliefs, at the centre, at the heart, and in his heart, was the freshness and simplicity of that original revelation, against which he tested everything. So it was all alive and in motion.

There was a regular group of members, and then visitors of many faiths, each bringing their energies to the place. Many leaders of the new religions that have sprung up, and the old ones that are growing now with new energy, passed through this place at significant moments in their lives. There were ceremonies for the seasons of the year, the lunar phases, events in the human realm. There were individual pathways and stations, where each might find his way. And there was Geoffrey, descending and ascending, meditating and celebrating, practising his way to … there is no sufficient noun.

And so he continued, settled, centred, located, protected. Until the day Rolf shook the earth, and the crystal shattered.

I sit for some time, animating all that is behind me, leave reluctantly the rose fragrance and enclosure of the arbour, walk the tangled path to the little gate. Looking back, it is like a beach at sunset, abandoned, deserted, the sandcastles beginning to collapse, awaiting the tide, life elsewhere, sad. And yet, again I have come close to the necessary emptiness, the space between. And now I must go on, follow the tale. I step through the narrow gate, into the wood.

At first the trees are well spaced, trunks bent, boughs spread, leaves creating a dappled, rippling light that moves in the breeze’s breath; thick air alive with the dance of pollen, the buzz of insects, the flicker of butterflies, the dart of birds; flowery undergrowth. I move as if through deep water, questions, lines smoothed from my face, thoughts silenced.

I cross the line where the fence was that had divided the wood between Geoffrey and Rolf, now, too late, gone … and I am in the plantation of pines. The atmosphere changes, from buoyancy to stasis. The trees are close-spaced, in rigid close rows, dark, bars all around me in long recessions, spiky black branches interlocked above creating sombre shade, the wind excluded, no movement of air or trees, no moving creatures except one tattered butterfly that lands and expires, no movement, no sound, except my own heavy footfall deadened by the thickness of fallen needles. I walk in gloom and silence, as if a bell jar has descended over me. The silence grows. From walking carefree, dreamily, I begin to awaken, my dreaminess fades, I look around, shiver, always the shiver, primeval fear. But also a shiver of anticipation. And within the usual shiver, the usual heat.

I walk on, step, by step, by step. The trees end, and I’m standing on the edge of nothing. I totter, about to fall, into the nothingness. Nothing prepares me for this, each time I am appalled.

Flat, lifeless, a circle of ash, walled in by the palisade of still and sombre trees, where nothing grows and nothing moves. I step onto the white ash. The wave of desolation rises up from under me, breaks over me; I brace, then relax, as the incandescence rushes through me. I fill with whiteness. I empty. I want to walk to the centre, embrace ultimate desolation.

Then I remember why I am here, withdraw from the ash, return to the grass, to the grassy slope, where there are shrubs and light and a movement of air.

I look up at the sky with its moving clouds, around at the flowers with their nodding heads, the waving grass.

This is the other half of the story. This is where Rolf lived.

PART 2

I

Who knows why the rich old man, Geoffrey’s father, picked Rolf out? Maybe such moments of change are just little whorls of chance, swerves that, as soon as they have happened, become invested with a significance which quickly becomes self-propagating. It is difficult not to react to being chosen by feeling Chosen. The paradox was, maybe always is, that the very lack of self-consciousness in the young man that struck and drew the old man began to depart as soon as the old man approached him and offered him recognition. But: the moment.

It happened at a resort complex in St Lucia, in the empty tropical dawn, a hectic red with pulsing waves of amplifying light singing in the silence, every object untroubled and cleanly itself. It began, this short sequence of events, in the disturbed ache one sometimes feel in the emptiness of first waking, that ache for something one has lost, or never had, which the old man felt profoundly as he awakened that morning. And yet feeling it, unusually, perhaps uniquely, he did not bury the ache by plugging himself instantly into the busy, chattering global network, of which he was a small but significant node. Instead he rose from his bed, threw a sheet over the blinking screens, pulled a robe over his grey-haired and sun-tanned nakedness, and went out into the empty dawn, padding across mosaic terraces and down marble steps to the swimming pool.

The young man, Rolf, was there. Not, as he should have been, cleaning the pool before any guests got up, but playing wildly in it, quite off his head, exploding like a bomb in the water, slicing into it like a knife, lying still and rocking gently at the centre of the pool at the interface, leaping from it straight up in a fountain of blood-red spray. The old man was reminded, as he watched, of a tiger he had seen, once, in an Indian river, almost unbearably alive. A man who had to be old before he had a chance to be young, watched a man who refused to be anything but young.

Rilke’s story of the prodigal son begins: “It is difficult to persuade me that the story of the Prodigal Son is not the legend of a man who didn’t want to be loved.” Rolf, like the prodigal son, had fled from the suffocation of being loved; for, to stay he would have had, as Rilke writes, to conform to their lying life of approximations, and to have corrupted the delicate truthfulness of his will. What he had sought, as did Rilke’s character, was the profound indifference of heart which sometimes, early in the morning, seized him with such purity that he had to run, and run and run so he had no time nor breath to be more than “the weightless moment in which the morning became conscious of itself.”

He had fled a happy and well-modulated life in the suburbs, and bummed and roamed, forgetting from time to time his resolve neither to love nor to be loved, settling, and then fleeing the mess. He had been taken up often by older people, and seen the hurt in their eyes when he had betrayed them.

But it was different this time, when the old man, shockingly, laid his hand upon his shoulder, and he whirled round and looked into the dawn-red face and the blazing red eyes with blinding white pins at their centres: he felt as if he was looking into the face of God. He was chosen, the Chosen One. And he could not resist. It was the rich old man’s speciality, offering the irresistible, using his infallible ability: timing.

But why did he do it with this young man, who was about his son’s age, his polar opposite, like a colour negative to the other’s positive, red against green? The scientist would give an easy answer: the genetic imperative to reproduce our genes is only half satisfied in each child, so our genes demand two children. But this young man was not biologically his. Enter the psychologist, who would tell us that the old man’s need for control had him choose his second child, and select one with that other package of genes.

But it was also the old man’s response to Geoffrey. Because Geoffrey, his son, was the one person who could resist his offers. And that, for a man used always to having his own way, was an ongoing frustration. Having chosen Rolf as his unresisting other son, he felt less frustrated. Balance, for him, was restored.

He didn’t make a big thing of his adopted son. He kept him in sufficient funds to indulge himself, saw him from time to time, settled upon him, in a secret fund, enough for him to live on after he died. And, in his will, he dropped the wood between these two only children.

At first, when the old man died, Rolf felt liberated. For he had always made his presence felt, and his interest smacked of voyeurism. As time passed, he felt abandoned. He missed being angry at the old man’s intrusions into his life. He wondered why. And realised that he had used his newly-gained financial independence to deliver himself from obligation, and in so doing he had isolated himself. With the old man gone there was no one to comment on his life, no echo to it. His was suddenly a silent world. His response was to indulge, gorge, glut his senses, with the absolutism of the decadent. But however much noise he made, the echo never came.

It was in the middle of this period of libertinism that he had received the summons to the wood. And in the style of his mood of mischievous knowingness and sardonic play that he had dyed his hair red and worn the scarlet thread.

And yet, as they approached each other, this other man, Geoffrey, his brother, was suddenly real before him; and as they got closer, closed, he felt, for the first time in his life, the beginning of a cracking, a breaking-up at his margin, like the edge of an ice sheet, imagined the cracks racing jagged to his centre, wanted it, feared it … extended his hand out from the edge, across the emptiness, to the other, stayed where he was … stepped back.

He quickly returned, though shaken, to his excess. But his heart was no longer in it. The moment in the wood had been a vision of something incorruptible. Hedonism lost its savour. He began, after this period of accumulating, to divest himself, of pleasures, possessions, money, whim. He imagined absence and emptiness. And saw, in the emptiness, the other.

Years passed before he returned. Sometimes he was working towards it, sometimes escaping from it, that moment in the wood, often forgotten, always there. He began idealistic businesses. He went on pilgrimages. He almost married.

At last, when the money was largely gone, and all other options, of careers, relationships, futures, had been foreclosed by his actions, and the only possibility, he suddenly realised, was to go to the one home he knew, he saw with the clarity of an illumination that he had all this time been backing himself, as one backs a highly-strung and mistrustful horse, inevitably and ineluctably, into a trap; with a sigh of relief acknowledged, as the collar dropped onto his neck and the shafts pressed against his sides, that in that trap was hope: that the wood was his necessity.

II

He made his arrangements, simplifying his finances, buying equipment, choosing the exact location he would live, with the certainty of one who believes he knows what he is doing, what the future holds.

So that when, one late summer morning he drove his flatbed truck loaded with his possessions, piled high with his life, up the track, into the sun, he was sure he was driving to his destiny.

He felt like one of the Victorian discoverers of the Nile, Bruce, Speke. And when the engine died never, he thought, to restart, he remembered Bruce’s rapture on arriving at the source of the Blue Nile; and then his despondency at the thought that his journey was only half through, that the dangers he’d passed all awaited him as he returned: and thought, that is not so with me, for there is nowhere to return to.

And when he stepped out of the silenced truck and stood silent in the midst of all the noise of the wood, he felt suddenly as if what was outside was inside too, that he was filled with the sun-dazzled air scented with pine and honeysuckle, in which pollen tumbled slowly in voluptuous motion, through which birds darted, through him too, he gasped, so that he was, inside, endless.

He made camp with practised efficiency, pitching his large tent at the edge of the slightly sloping clearing, close to a bubbling spring. He dug toilet- and waste-pits to one side, then began arranging the tent.

He spread colourful rugs, hung up drapes of light sari cloth. In one room he placed a camp bed, sleeping bag, bedside table; in the other a small table, folding chair, bean bag, small bookcase with a dozen books, music player with ninety-nine tracks, vase, and three small pieces of sculpture: a smooth Eskimo soapstone carving; an angular metal maquette; a leaping panther in wood. He set up his kitchen in the porch, then went to pick flowers.

He spent hours arranging the living room: moving furniture, placing the sculptures first here then there, turning them over in his hands like a blind man; re-ordering the books, reading a page in this one, a paragraph in that, lying down, chin on hands, to read a whole chapter; scrolling through the list of tracks intently, playing snatches, then one over and over, lying on his back. His whole life to date was in this room, concentrated, focussed, relived in illuminated snapshots, experienced as a tumbled succession of vivid moments.

It was evening before he stepped out into the clearing. It was flooded with white light prismed at the edges by his dazzled eyes. In the trees all around birds sang with a clamorous intensity, as if rushing to complete their day’s quota of songs; the trees were thick charcoal slashes against the white sun; the sky curved over him like the inside of an egg shell, clear blue with a sharply-cut moon and one star. The sun slid into pinkness, the sky turned lilac; the birds suddenly stopped singing. There was silence. Emptiness rushed into the vacancy, filled him. He was made of glass, perfectly formed, everything working, without thoughts or feelings, registering exactly. The darkness settled upon him like a cloak onto a bird’s cage, he within it silent and inviolate.

He slept a dreamless sleep. He awoke slowly, his head empty as a balloon. Eyes closed. He felt the sun on his face through the tent fabric, listened to the rise and fall of the light wind in the trees, the intermittent movements of creatures in the undergrowth. Then he heard a noise closer, in the room, a faint patter. He opened his eyes.

A mouse, on the richly-patterned carpet, two yards from his head. Sat back on its haunches, long tail curled round, nibbling rapidly at a seed in its paws. It dropped onto all fours – he heard, oh so faintly, paws land, claws catch in the wool – and did not move. He could consume it, devour it with his eyes: velvet ears, jet eyes, shaded hairs of its coat as detailed as a silver point, utter stillness. Absence of life. Then it moved forward; motor switched on, moving on wheels; stopped, a switched-off toy. He extended his arm slowly, lifted his hand slowly, so that it appeared to be on his palm, felt it suddenly alive (he had kept mice as a child, it all came back, he was there). If he dropped his hand an inch it was a stranded toy; if he raised it he felt the soft feet, the needle claws, the warm body, the palpitating lungs, the heart flickering like a bird’s wing, a blur so fast it would wear out within a year but now, at this moment, on his hand, purely alive. He felt as if he had never known what ‘alive’ meant before. He slid out of his sleeping bag. The mouse moved to the door, stopped as Rolf pulled on shorts and sandals, and was gone.

At the tent mouth, dazzled, he couldn’t see it, saw it, tiny and defined in the vast wash of the clearing. Then an open hand extinguished the sun, a bomb fell, a tawny parachute landed delicately, decisively; a taloned foot closed around the shadowed mouse, which squeaked once, and the falcon shuffled its wings closed, settled, stood.

Barred breast and cloak wings facing Rolf, sharp head side on, glittering eye on him. Its headlong descent and clean take had thrilled him, the assured way its wildness had taken possession of this domestic place had subdued him. He hovered like a supplicant. Then it lowered its head, eye all the time upon him, hooked its clean, curved beak into the palpitating creature, tore it, blood spurted.

Rolf came to, erupted in a fury: against this creature that had descended into his made and remembered world and was acting now as it chose; against this offence to innocence; against all careless authority. He grabbed the spiked pole that held up the awning and threw it like a spear, drove it with all his will at the falcon’s heart.

With a waft of wings the bird lifted, evading the spear with ease, came violently at him, beak open, tongue hissing, veered off at the last moment, its wing brushing his face – he would feel it forever, that slap, stroke, touch, hear the brushing sound, find himself fingering the bare hot place as one does a scar – gyred up into the sky.

He watched it rise. He felt such yearning. The spear had pierced his heart, there was a tugging string from it to the falcon, he must follow the falcon to arrive at where he must be.

At first he could follow, as he loped easily, a path, soft and mossy, through neglected coppices, the sun dancing through the branches, the falcon visible.

Then he ran full tilt into briars that closed around him, sank thorns into him. He cursed his nakedness, used a stave to flail a path that only buried him deeper; at last pulled back, his skin pricked all over to trickles of blood. He searched for a way through, thicket upon thicket, at last saw a clear way two yards beyond an entanglement of thorns. He took a deep breath, charged, yelling like a savage, swearing at the tearings, burst through and rolled his flaming body on the wet grass until the pain had settled to the individual stab of each wound.

He stood up, panting, lost. The falcon spiralled above him, as if waiting, canted, glided away.

More woods, more paths. Then opening out to a flat expanse of emerald green, laid out like a welcome carpet. Into which Rolf sank, in two steps, to his knees, and no way round.

A tree fallen across, narrow, moss-covered, unstable. He took off his sandals, stepped on and, not looking down, began to cross. Feeling each step, feet sensitive and prehensile, knees flexing, eyes focussed on a heart-shaped scar on a tree on the far side, a thread connecting heart to heart, absorbing the thread with each step like a spider, attention on feet and heart. The tree slipped, he steadied himself, resumed, arrived.

Elation as he bounded forward with new assurance, over fallen trunks, between invading shrubs, under hanging branches, flying past everything, glimpses of the bird sustaining him.

And then he found himself faltering in his pursuit, his legs become heavy as if his blood had thickened, his mind doubtful, he slowed. Not from fatigue, but from something formidable in the atmosphere of the place that he had so carelessly rushed into. He looked around.

The trees towered above him, branching and twisting, vines and mosses hung flesh-like from vast limbs. The undergrowth was thick, not with the soft rampancy of secondary vegetation but the solidity of slow dense growth. The tracks were narrow and sinuous, fugitive, the paths not of man but of animals, that would, he knew, lead mazily round, never leaving the wood. Darkness prevailed. A place of bears and boars, wolves and wildcats. The ancient wood, never lived in by man, except hermits and outlaws, who each in their ways partook of its wildness. Crossed by travellers in trepidation. Visited by hunters with bravado. A place not to tame but to placate, which no man entered with an axe except the youth on his manhood quest, terrified by visions of the cut tree shrieking and closing around him. A place of offerings hanging from branches, menstrual blood smeared on boughs, dead babies stuffed into hollow trees, limbs nailed. This tiny remnant of the primeval forest (sixty days to cross Hercynia, two months, day after day of this) untouched, intact, preserved, man’s connection to a wildness now only dreamed of.

And he had wandered blithely in. As he had wandered once into a waterfront bar, with growing awareness of the fractional diminution of conversation, the exchanged grins, the way the press opened before him, closed behind. He’d got out, just. No heroics (one clenched fist and he would have died), rather, a focussed sensitivity to nuance, making of himself a human stealth aircraft, slipping out on the membrane that surrounded him. But this, this was awful, haughty, magnificent! He could be wild, lose himself, be one with this …

He slapped his face, gripped a thorn to rouse himself from bewitchment, looked carefully, stepped softly, moved purposefully, and, at last: as he stepped, as if through a membrane, from the ancient wood into the domestic, he felt both great loss, that he was leaving behind something he would always miss, and an exact sense of his self, of the precise outline of himself and a centred knowing, for a single moment, of exactly who he was.

Energised, he resumed his pursuit, sure now that he had passed a test, that he would find the falcon, his totem bird.

And there it was, perched on top of a large rock, in front of a rock face like a small quarry.

As he approached, it lifted, caught a thermal, spiralled up, became a black cross. X marks the spot. It was a red rock, incongruous against the green rock face. Brought here. His destination. Behind this rock – or inside it? – was the treasure. A single word, a hidden lever, a tiny crack through which he, become mist, could pass.

He searched. Nothing. It was simply a large rock, an erratic brought by a glacier and dumped, with no reason to be here beyond the action that brought it.

Above him the falcon ceased to rise, slid sideways across the sky and, with a flick of its tail, disappeared. Rolf smiled. He laughed. He lay on his back helpless with laughter. Then he trekked back to his camp, which was very close, and cooked himself a very large breakfast.

III

He practised his original intention: to let things happen. He had come, he reminded himself, not to a task but to a place Not to do but to be.

He lived without pattern. But not lazily; never had he lived so intently, been so responsive to his surroundings, and to the feelings within him. Often he was at the very edge of what is, the here and now. Sometimes he allowed himself to sink into memories and dreams.

As ideas came to him, he improved his camp.

On the second day he made a basin for the spring. The water bubbled out at the base of a low cliff, ran over bright green moss, sank into boggy ground. He spent half a day gathering stones, searching the paths and undergrowth, carrying armfuls back in wagered trials of strength until his arms throbbed and his head swam. He constructed it slowly, carefully, with no plan, each stone leading to the next, never stepping back. With his legs numb in the cold water, his head burning in the heat of the sun, he was a creature of two realms, uniting them with his purpose. When he looked at it finished, the graceful oval bowl that the spring both scoured clean and kept filled, it was as if it had always been there. The mosaic of water-bright stones was like the imprint of a giant tortoise shell. He ached, was drained of all energy, felt clean.

The next day he made a solar water-heater with a black bin liner, and a shower from a nail-holed bucket. After a long day gathering firewood, his voice rang through the wood as the water flew in rainbow drops. He climbed into a tree and lay like a leopard along a branch to dry.

On hot afternoons he would lie on his bed, the sun warm on his face, dappled shadows playing as the fabric of the tent bellied and sucked under the fitful breeze, and dream.

He dreamed he was an Ellison, creating his own wondrous domain of Arnheim, a precious glory that would be secretly known. A Zarathustra, living here for a decade with his eagle and his snake, becoming wise. But not, then, wearying of his wisdom, glutted like a bee with too much gathered nectar, needing to go down; instead waiting, content, his nectar available for those who could reach it, like those strangely-shaped flowers that only a certain bird’s beak can reach into. A Bruce, reaching the source of the Nile, here, his spring. But not, then, returning; rather, diving down, into the lifeless ocean, swimming through the measureless caves, going back, and back, to emerge in … why not? for wasn’t the Nile the fourth river of Eden? Marching round his spring, he chanted:

“That with music loud and long,

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread,

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.”

He loved being alone. He loved shrinking to a single point of perception, lying on his side, watching a crossing of ants, marching and counter-marching, ball-and-pin things, jostling and forever in motion, carrying white plates of mica. He imagined himself carried like one of those flakes, down the hole, into their colony – what marble palace were they building within? – being incorporated into the architecture and watching, silent witness, as he learned the lives of ants.

He loved expanding to the size of the earth; as evening came, the sun a red lozenge that he would catch on his tongue and swallow down (such heat!), its molten heat spreading through him, the wood a lively domesticity slowly quieting, bedding down under his watchful eye, the perfect curve of the darkening sky and the emerging stars, each not there, then there, like travellers arriving, signs of mysteries that he would unceasingly and sleeplessly contemplate through the still night, as everything slept under his protection, while he kept his necessary vigil.

He loved, as he performed his exercises, being exactly his flesh-and-bone, skin-located self; the air emptying from the space he moved into, occupying the space he left, weight flowing within him, his limbs filling and emptying. When he finished he stood in the sun and felt the light flowing over him like a soft golden liquid, defining him exactly, and the stillness at his centre.

Best of all he loved being himself, the self he was in each precise moment.

Gone, the social self that had to remember to approximate to some consistency, in order not to confuse. Left behind, the self that had to monitor the reactions of others to him, so he could imagine their perceptions of him, then alter his behaviour so their perception was closer to the person he was at that moment. For he hated the approximateness of social intercourse, in which people see what they want to see, misunderstand, assign you to a category and thereafter treat you according to that category, make you relative. He loved being absolute.

He had lived there alone (a local man collected notes and delivered goods to a place at the edge of the wood) for a month, when the weather broke. New to the area, he hadn’t registered the weather as exceptional, had taken it for granted.

But in the villages around, as far as the town, they had remarked on it, that memorable summer month; and those who were ready had been changed by it. That time of rosy dawns you would hold your breath at, such was their promise. Days of sunshine so warm it was as if you had shed a skin. Air so clear you could see distances never seen before. Afternoons when doors and windows long shut were pushed back on rusty hinges, hinges were at last oiled, so that inside and outside were one. Clouds small and white and ever moving and changing. Dreams that, you suddenly knew, could be made real. Sunsets so long and magnificent that people found themselves walking to high places to witness, stopping what they were doing and just looking, taking a long-forgotten hand in theirs; or sauntering alone, bathed in the ecstasy of it and meeting, at last, one walking towards them. Nights that concealed those who must be hidden, shrouded those who needed comforting, were alive for those who would keep vigil, a wonderland for those whose time it was to play.

One afternoon, the delicate breeze ceased, the atmosphere grew heavy and close, the air thickened, with the taste of metal in it. Children became overexcited, colleagues quarrelled, people began to sweat. Clouds built up. The livid sunset took place in a narrow gap between the dark earth and the heaped clouds that towered, bruised and threatening. The clouds moved like a slow avalanche.

Drawn out of his tent by the change, the insects close around the lamp, the oppressive stillness, the strange silence, as of held breath, Rolf climbed high into a beech tree to watch.

The vast clouds were lit intermittently from below by silent lightning, filigrees of energy flickering between the two black masses, one fixed, one moving, at first on the circumference of a circle of which he was the centre, then slowly turning, like a massive beast that had scented him, moving towards him, coming at him.

The air crackled. His hair stood on end. His skin was clammy with sweat. The moon, the stars, the sky were progressively swallowed by the slow, heaving mass. The raindrops came, fat and intermittent, and then small and continuous. Then the wind, at first in gusts that swayed the tree, soon with ferocious force, tearing at him, whipping branches across his face, plunging his foothold from under him, reaching like a hand to swipe him from the tree. He struggled out of his shirt and tied himself to the tree and held on, sometimes riding the tree like a sailor on a storm-tossed ship, sometimes hanging on as if to a bucking animal, gasping with the air torn from his lungs, deafened by the uproar, terrified. Then the hail came, stinging pellets of ice that peppered him like buckshot, and lightning, flashes sudden and blinding, and thunder that felt loud enough to crack his skull. ‘Yes!’ he cried once, the word torn instantly from his mouth and blown away like a leaf.

He stood, hung there, for he knew not how long, battered almost to insensibility by the storm. The slackening wind and pattering rain revived him. In the sky was broken cloud, stars shining between. The wind faded to nothing, the rain stopped.

He shivered, untied himself, wrung out his shirt and draped it over his shoulders, but did not descend.

Around him the sound of dripping trees, below him a stream in spate, above clouds moving slowly across a clear, starry sky.

But there was still electricity in the air, and lightning. Not sheets now, but bolts, precisely hurled spears. He felt exposed, high in the tall tree, in the clear air, and frightened. But he did not descend. One bolt struck to the left of him, with a deafening clap of thunder, a chemical smell, and then the smell of smouldering vegetation. And one to the right. He stared up at the large metamorphosing cloud.

And then – he swore that this is what happened, and who knows whether his experiences of the month, and of the night, had produced in him precise sensitivity, or hallucination? and lightning anyway is so little understood – the cloud split open and a bolt of lightning flashed down towards him, like a tongue, at him; and stopped, did not leave the cloud, was reabsorbed, dissipated within it, the cloud closed up, there was a muffled rumble and the cloud, the last cloud, passed over his head and out of his vision.

The sky was clear. He climbed slowly down, and crawled into his sleeping bag. After reliving many times what had happened, he slept.

But when he woke he didn’t feel refreshed. And where he had become used, each day on waking, to emptiness, now there was a question. And the question kept drawing his attention as a hole in a tooth does the tongue: have I been spared, or have I been denied? And when he went to seek clarity outside, he found that the storm, far from clearing the air, had left a gluey mistiness that occluded vistas and drained colour and definition from his once-radiant wood.

He felt indecision within, and obscurity around. And the question existed, not as a problem to be solved, but a thing to be obsessed over, like a coin that he turned over and over in his mind with first this, then that face uppermost. And the question was a fork in a road that he could not proceed along, until he decided, until he chose.

He closed around that question, that fixation upon turning the coin, unable to move. He ceased to take an interest in the wood, he held himself still while the wood changed around him, he performed his tasks automatically, without awareness, for a long time.