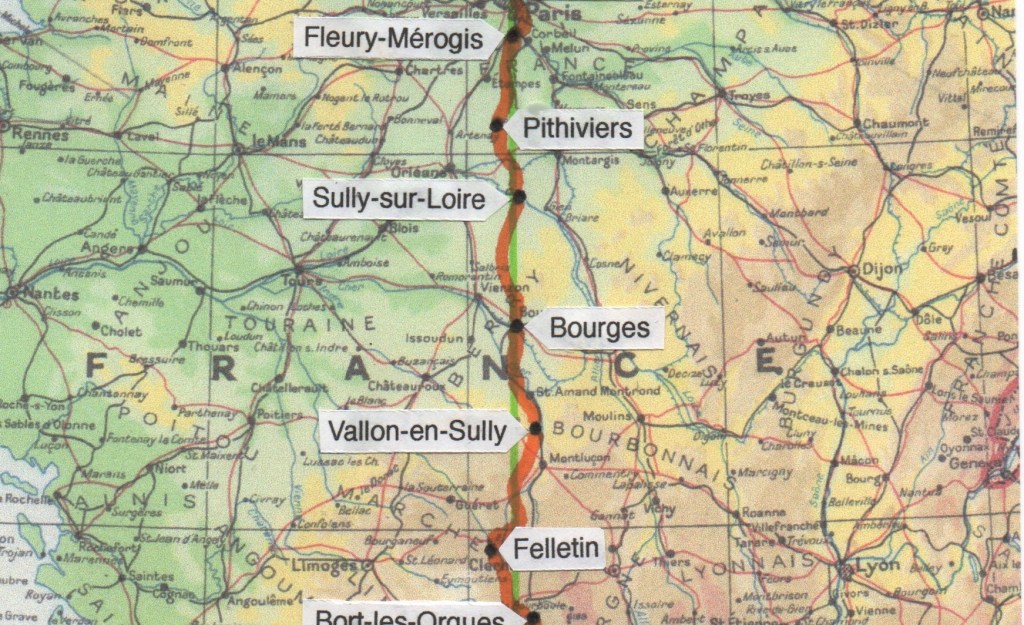

Day 9: Pithiviers to Sully-sur-Loire, 74 miles.

The deportation-camp. Irène Némirovsky. The hunting ground of the Forest of Orléans. The Count of Toulouse’ final surrender. ‘The Name of the Rose’. The end of the troubadours. Gribouille. Love’s arrows.

I fall asleep to the dream that I am in my own sweet corner of la France profonde, having slipped warmly into my sheet sleeping-bag (no down sleeping-bag – who needs a down bag in June?) in a pair of shorts as the last light fades from the sky, and roosting birds serenade me from the softly whispering trees.

I wake to the nightmare that I am lost in Siberia, frozen to the marrow, having pulled on every garment as the night has gone on, getting ever colder as an icy wind knifes through the tent wall, waiting to freeze to death.

My first night camping began with the late arrival of a family in a motorhome, which, on a large, empty campsite, the driver chose to park opposite my lone tent, backing in so his headlights blazed through the tent fabric into my face for an hour as they prepared and ate a multi-course banquet using dozens of metal pots.

Then, as darkness returned, there arose out of the silence the sounds of a cat-skinning abattoir, screechings, yowlings, blood-freezing screams that continued for most of the night.

Then the wind got up, and for the rest of the night the security lights, my tent the focus of several of them, switched blindingly on and off, triggered not by movement but by the Brownian motion of atmospheric particles. And it got colder, and colder.

The only gain from camping is the night sky. Which was spectacular when I crawled out for a pee. To be caught, as I stood up, pants down, in the cross-fire of the klieg-lights.

In the morning it takes half an hour walking up and down the lane to recover any semblance of bodily feeling, and the minimum of brain activity needed to decide what to do next. On the way I passed the cat abattoir, a rookery of birds smiling as they sleep, like drunks after a night out.

First, a cup of tea. Second, another cup of tea – no, no, pack up, go into town, find breakfast.

For some reason – I still believe I’ve entered a dream of France – I expect there to be breakfast in the town. That I will walk into the right bar, and speak in the right way, and boiled eggs, and croissants and tartine avec confiture will appear, and good coffee, the smiling moustachioed patron in his long white, if a little work-worn, apron, clucking as I tuck in, inquiring anxiously, ‘encore?’ I remember when it was routine in a bar at breakfast time to put a basket of croissants by your coffee. You’d be charged for those you ate, then it was passed to the next customer. Now sugar comes not in a wooden box of irregular cubes but in paper tubes. I remember …

I go into the first bar I find, and ask for a grand crème. The woman is thin, energetic. She is vigorously, violently washing the wine bottles they use as water carafes. I imagine that, in a good mood, in the evening with her familiar customers, she is a friendly patronne. At 8am on a Monday morning, with an oddly-garbed foreigner, she is not. Without looking at me, working with brittle energy but without grace, she says very quickly something incomprehensible that doesn’t sound promising. I decide to be Mister Reasonable, and say if it is too much trouble, that’s not a problem, I can go elsewhere. In the time it takes to me to stumble through this, she has made coffee, boiled milk, poured coffee and milk into a cup and plonked it down in front of me. It is an ordinary cup. I put down the money for a grand crème. She pushes a euro back to me and takes the rest and smiles the big, sincere smile, see I’ve really got a heart of gold. No, a heart of gold would have made a grand crème.

On this off-balance note I leave Pithiviers. It is an unsettling place, with its strangely-shaped iron church steeple, its vast, open, windswept hilltop square that even in June feels full of winter blizzards.

And it is a place full of the unspoken. It is Lago in High Plains Drifter. Are there people here who remember the deportation camp? There must be. And people who made money from it.

The camp had been built before the war for the expected German prisoners-of-war. The Vichy government of Pétain used it first for political dissidents and then, after the 14 May 1941 roundup of French Jews, as a transit camp. In 1942, 6,079 Jews were sent from here to Auschwitz. 115 survived. Among those who died was Irène Némirovsky, whose account of the German invasion and early days of occupation was discovered and published in 2004 as Suite Française, one of the few contemporary accounts of the ignoble chaos of 1940.

In 1957 a memorial was raised on the site of the camp, near the railway station. In 1994 a plaque was placed on the station. I freewheel down the hill away from it, and head for the Forest of Orleans, and the Loire.

I look for Meridian markers. At Courcelles there is a small ash wood, a triangle with its apex pointing north. This seems to be the limit of the tree planting, small woods, like the patches of millennium planting in England. There are markers at Nancray and Nibelle.

But, really, what’s the point of simply visiting markers from the millennium, when nothing has happened since? I need to think about the Green Meridian. But not now. Now I turn west and plunge into the Forest of Orléans.

Although ‘plunge’ is hardly the word. I had high expectations for this. At 35,000 hectares it is the largest forest in France, and state-owned. I had expected an ancient woodland, with rides, coverts, and the feel of a place with memories from the time of the troubadours, of knights and ladies.

I find it divided into neat parcels of trees by arrow-straight rides, with crossroads of four, six, even eight radials.

These were laid out for hunting: the lateral rides are for the chase, the radials, created later, for the shooting. I imagine game driven across, enfiladed, mown down as they cross the road.

The woodland itself, oak (60%) in some areas, Scots pine (30%) in others, is given over to timber production. It has the stillness and emptiness of the monoculture. The only interest is the strong, resinous smell of sawn wood from the large lumber mills I pass.

I had expected something wilder, looser.

35,000 hectares is, after all, 135 square miles, big enough for rambling pathways and cycleways, mixtures of trees and lakes, habitat diversity. And yet here I am, at a crossroads, by a cast-iron signpost that points down eight straight roads, like points of the compass, next to a sign that says that walkers are likely to encounter stag-hunters on horseback on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and gun-toting hunters of wild boar and deer on the other days. Except Sunday.

After the Revolution these forests, previously the preserve of nobles and the church, were opened up to all. But in the 1820s, under the new king, restrictions were placed on hunting and wood-gathering. The forest is now divided into rectilinear plots of hunting rights.

Close by, within sight, is a national observatory, but the road to it is closed to the public.

Sorely disappointed I turn south from Engrannes, pass lakes used for fishing, and reach the canal d’Orléans.

It was constructed in the 1690s by a businessman to transport timber and coal. Eventually it was part of a system that linked the Loire with the Seine. This was over sixty years before the first significant canal in England. Again, I ponder why France, the richest country in Europe, scientifically advanced, well-populated, was so late to industrialisation.

But the ruling class of the eighteenth century had no need of industrialisation: there were plenty of peasants to labour and tax; no middle-class to push them aside or demand the sort of products English industry was producing; and all the luxury goods they wanted were being made in Paris or traditional specialist centres.

And I ponder why this canal, closed in 1954, was simply abandoned, until the state decided to renovate it for leisure use. In England there would have been local volunteer groups campaigning, and working to open up each stretch.

There seems to be a lack in France of what we call ‘civic society’. There are no real equivalents of the National Trust, RSPB, Ramblers’ Association, Civic Trust, Woodland Trust etc. It is the State’s job to do this stuff, while the citizen focuses on self, family and friends.

It seems to go back at least to the Revolution which ‘proclaimed the rights of men and citizens as individuals, and emphatically rejected groups’ rights. There was nothing between free and equal individuals and the state.’ (Howarth & Varouxakis.) Which is perhaps why the French are prepared to pay a higher a proportion of their income in taxes. Maybe this is another reason for the lack of interest in the Meridian.

I cross back over the Meridian, to the village of Lorris, because of Guillaume de Lorris. Around 1230 he wrote the first 4,000 lines of The Romance of the Rose, a poem of courtly love, of which Huizinga writes, ‘Few books have exercised a more profound and enduring influence on the life of any period.’ And: ‘Just as scholasticism represents the grand effort of the medieval spirit to unite all philosophic thought in a single centre, so the theory of courtly love tends to embrace all that appertains to the noble life.’

If my education, in its scientific and intellectual attempt to understand and codify the world, was the modern equivalent of scholasticism, then romantic love was my way of embracing the noble life. I was one of those sucked out of the working class by that curious hoover the eleven-plus, to add to and energise the middle class in the one-off post-war doubling of the administrative class. Deracinated (Richard Hoggart writes of us being ‘uprooted and anxious’), and supposedly grateful for the opportunity to be grafted onto (into?) bourgeois society, I found it intellectually stimulating, ideologically suspect, and emotionally numbing. Through school, emotion was the sentimentality of pop songs. At university I added Romantic poetry and literature. And although I was forever seeking it with those at the racy edge of the middle class, especially art students, when love hit me, it knocked me for six, changed my life.

Lorris was an important hunting centre for the Capetian kings; it would be to entertain this court that Guillaume composed his Romance, which was much influenced by the love poetry and song of the troubadours of the South.

In 1242, Raymond VII, Count of Toulouse was summoned here by Louis IX finally to capitulate to the French crown, after 30 years’ resistance to the Albigensian crusade. It was the end of the independent South, of a Languedoc society, based on courtoisie, where the troubadours thrived.

Around 1270 in Paris, Jean de Meun added 17,000 lines to the Romance. In his continuation, the poem of love becomes a clotted intellectual allegory. The contrast between the two parts exemplifies the victory of Northern universities over Southern courts, the victory of the scholastic over the poetic.

Lorris is a sleepy, empty place. Two men lounge outside a bar. I buy orange squash in a general store, with little for sale, run by a woman who laughs a lot, but as if to stop herself crying, oddly tragic.

The church modulates between Romanesque and Gothic in a comfortable, non-ideological way, with a Romanesque porch, a Gothic window above, and topped by a sixteenth century brick clock tower, surprisingly harmonious.

I head south-west, on a straight road through the forest, heading for le Carrefour de la Resistance, the memorial to le maquis de Lorris.

The Loiret was an important centre of Resistance, with many deportations. In August 1944, 50 maquisards were slaughtered here. There are giant sequoias close by. But the road to the memorial is closed.

A dramatic arrival at the Loire, at Sully-sur-Loire. There is long bridge over the wide river, and the town is guarded by a fairy-tale castle of white stone, with round towers and conical slate roofs, rising up from a moat.

It was built to secure the river crossing, and added to by Henry IV’s minister the Duke of Sully from 1600. The five-arch bridge is recent, replacing the suspension bridge built in 1839, which was destroyed by the retreating French in June 1940, then again by Allied bombing in June 1944.

It reminds me of the phases of the war here: the German invasion sweeping south, the Allied invasion moving north. In the time between, France was a partitioned and occupied country. The suspension bridge was rebuilt six times, finally falling down in 1985, damaged by fierce frosts.

I go straight to the Office de Tourisme, where two young men eagerly demonstrate their English and their knowledge. Disappointed that all I want to know is the location of the campsite, one directs me there, adding hopefully, ‘and if there are no vacancies, please come back and I will telephone around.’

The campsite is by the river. It is a large, efficient site, mostly motorhomes, the few tents are, pleasantly, located on the river bank. The woman at reception is friendly, intrigued by the out of the ordinary. I book two nights. I’m having a break from daily packing up and moving on, a lateral day, along the placid continuity of this great river, its meandering flow west, under the given of gravity. A corrective to my headlong willed rush south.

I make tea, and sit by the river that murmurs softly past. The sun shines, glittering on the water.

There are ducks and water fowl on soft sand and among thick grass. The Loire must have been in Guillaume’s mind when his narrator writes: ‘I bent my steps towards a river which I heard murmuring close by … not quite so great as the Seine, but wider. Never before had I seen that stream, which was so beautifully situated, and I gazed on the delightful spot with pleasure and happiness. As I cooled and washed my face in the clear, shining water, I saw that the bed of the stream was all covered and paved in gravel. The fair broad meadow descended to the water’s edge.’

The narrator of The Romance of the Rose has a dream: on a perfect May morning he arrives at the Garden of Pleasure, a place of surpassing beauty and perpetual enjoyment. The garden is enclosed, access is granted only by Idleness.

Inside, gazing into the Spring of Narcissus, taking care not to look at his own reflection, he sees all the beauties of the garden reflected. Then, in the Spring he sees, beauty of beauties, the rose. As the narrator approaches the rose, Love shoots him with his arrows, infecting him with the divine madness of love.

I have been shot by the arrows, infected with the divine madness of love, three times, at intervals of decades, each time out of the blue.

The first time, I discovered pleasure, idleness, the spring of Narcissus, the beauty of beauties. It flew me high, cast me down, fused circuits of feeling, knocked me off the rails of my given life, at first into a wilderness but then led me at last to the making of art.

The second time was the recognition of the perfect opposite, the mutual attraction of magnets, the sudden coming-together energising and lighting each other up, while laying waste all round. And with sudden, destructive reversals that followed attraction with repulsion, love with hate. The beloved was the muse, bringing art of a new quality. But the repeated reversals eventually drained the magnetism. Time to eat.

I walk along the river bank towards town. The river is wide, shallow and flat, with sandbars and islands. ‘Loire’ means ‘alluvium’. It seems odd, seeing this benign, slow-moving stream, that it is called ‘the wild river’. But this is because its shifting shoals, summer droughts and winter surges have always made navigation difficult. ‘One arch is sufficient for the passage of its waters when it flows at a depth of two or three metres only above its sandy bed; fifteen arches are not sufficient when it rages through them on a level with their keystones.’ (Ormsby.)

By the bridge is a marker for the water high-point; it is above the top of the bridge.

Although well used since earliest times, with quays all along it, navigation was quickly abandoned after the coming of the railways. Imagine the different history of France if this, the longest river, across the middle of the country, with timber and sheep, coal and iron in the uplands, rich agriculture along its length, had been easily navigable along its length, with a harbour at its mouth! In the Hundred Years’ War it was the boundary between English and French territory.

I walk into town. There are few places open, not even the kebab shop. In the bookshop window, ‘Le Bateau-Lavoir dionysien’, which promises tales of wild goings-on at Picasso’s studio in Montmartre. But is about a laundry-barge on the river at Saint-Denis-en-Val. (Inhabitants of towns called Saint-Denis are dionysiens, perpetuating Suger’s myth that Denis was Dionysius the Areopagite.)

There are many local books: on Clogs and Clog-making; Salt-smugglers at the time of the gabelle (salt tax); Miracles of the Loire; Gauguin in Orleans; Criminality in Berry in the eighteenth century; In the pays of Sologne … This interest in what has gone allows us to romanticise the past, to (at a safe distance) mourn its passing, and be silently grateful that ‘progress’ has moved us on from then.

Next door is a shop filled entirely with products made of wood and straw: carpet-beaters, bellows, straw-seated chairs, shopping bags, baskets of all shapes, straw hats, hay forks, all immaculately made. And made for display.

Unlike the rough-and-ready but serviceable ones made by our neighbour in the Aveyron, and by me under his tuition – a basket made in an hour from hazel and willow, a rake re-handled in fifteen minutes at dawn with a freshly-cut ash bough. And I remember the basket-maker in the village, with knotted fingers and bowed back.

Curious, this world of craft revival, items for conspicuous display rather than practical use, often made by well-paid middle-class professionals, rather than the ill-paid artisans who made them when they were actually used.

There is a shop, closed down and metal-shuttered, with, in that art-nouveau-influenced early-twentieth-century script of so many older French shops, in big letters, ‘Gunsmith’. Around it, in smaller letters: ‘Cutlery, Gifts, Men and Women’s Clothes.’ What a mix! Are they ‘lines’, brought by commercial travellers? Or an illustration of what could be sold in a small town, before cars and buses made larger centres accessible?

There is little choice of eating place, but fortunately my standby, the Chinese takeaway. I select my dishes at the glass-fronted counter. They are identical, the rices, the noodles, the meat dishes and salads, in identical plastic pots, to those in the place I ate in Paris. I imagine a factory in central France – perhaps next to the Norbert Dentressangle lorry park – where the dishes are prepared in great vats, decanted into identical polythene containers and shipped across the country to be displayed in identical takeaway counters. There would be the ‘Chinois’ line, and the ‘Libanais’. The ‘Indien’ line is coming soon. I select rice, noodles, and chicken with black mushrooms. They are microwaved and brought to my table on a china plate, with cutlery, serviette, a carafe of water, and a bottle of Chinese beer, and served with finesse. I eat with relish, writing in my notebook from time to time.

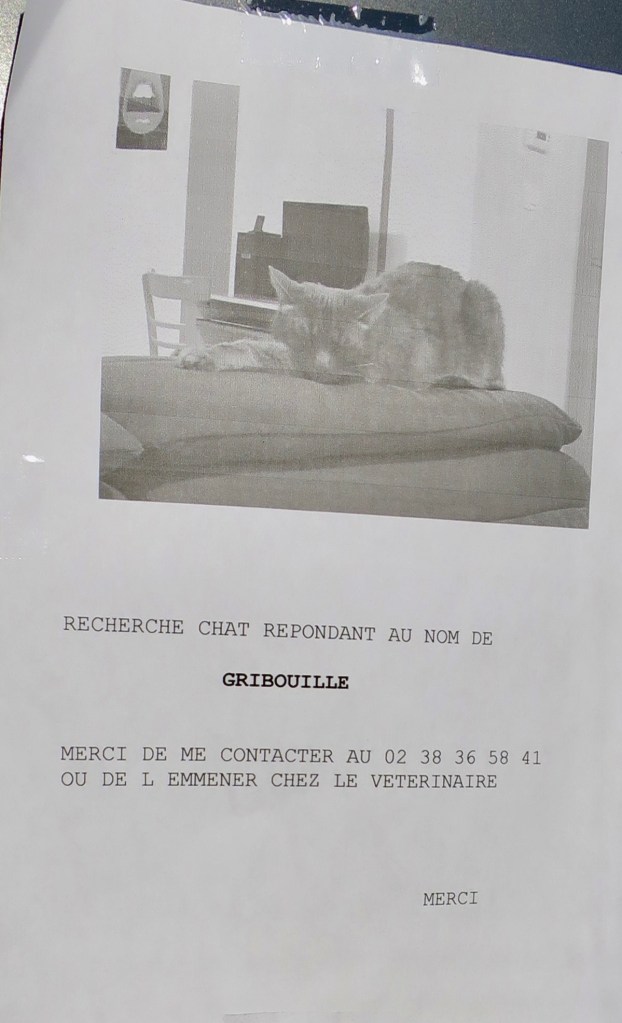

Walking back – how it reminds me, this small town, of my home town, on a summer evening after the shops closed, the streets filled with sunlight, a town I inhabited alone! – I pass a notice on a lamp post about a lost cat, ‘answers to the name Gribouille,’ and a phone number.

A rather lovely word, Gribouille. It means rashly naive, ‘someone who throws themselves into the river to get out of the rain’. It was also the name of a popular TV puppet who taught children to draw (gribouiller means to sketch). And of an intense, troubled French chanteuse of the sixties who died of drink and drugs at 26. I try to imagine who Gribouille’s mistress (I’ve decided it’s a woman) named her for. Is it to remind her of a loved TV character from her childhood? Does it describe the endearing scattiness of the cat? Or perhaps it reminds her of her own rash naiveties, good and bad, that have made her who she is. Maybe she’s a no-nonsense schoolteacher, settled in job and life, who plays, late at night, cat on lap, the songs that enchanted her student days, that take her back there, perhaps to when she had something of the troubled chanteuse about herself. I imagine stories about her and her cat, paths not taken. I always see a woman alone, in an upper room, like Rapunzel spinning, like the Lady of Shallot with her mirror, as I pass.

The walk back across the long bridge, looking downriver, west, stretches out the view horizontally, like a wide Flemish picture, pierced vertically by a single sharp silhouetted church spire. The wide river glitters with the low sun that shines between golden clouds. There are sandy shoals, grassy islands, small still stick figures of men fishing, evening-busy birds. The foundations of the old bridge below remind me of home, by the new bridge. The view recalls a shared walk on the Severn water meadows at Tewkesbury. For me, on the bridge, something has changed.

Is it the place? The turreted castle? Thoughts of courtly love? Or the sudden halt in my headlong rush south, the dissolving of the bubble of self-containment in which I have been travelling, inside which my life has simplified to practicalities, desires have progressively fallen away, until all that matters is the journey? I can understand, now, those who cycle on and on, around the world, and then around the world again, a life simplified to the setting and achieving of goals, in which there is no arrival, for there is nowhere to arrive. Whichever, it is not an evening to be comfortably alone.

But I am alone, midway across this long, wide, empty bridge. I reach for my notebook, and pen. No pen. And my reserve pen. Gone. Panic. I hurry to reception at the campsite.

The owner sits in her globe of light in the gathering gloom, attractive, reflective. I ask if she has any pens for sale. She looks at me, ponders, then says, in French, no, but I have something else. She reaches into a drawer and pulls out a pen that advertises the site. As she hands it to me, with a smile, she says, or I think she says – ‘then when you use it you will remember us, and write the light.’ I smile and thank her. Of course, on this special night she has seen that I am different, a writer, for the French notice and respect these things. She sits in her office and watches travellers come and go, and has stories for each of them, and scraps of their travels stay with her, and shreds of herself go with them. Maybe she is chained by circumstance to this place, condemned to be the eternal observer. Or perhaps this is the perfect place to dream of possible journeys and other lives.

Ah, the romantic French, ‘you will write the light.’

I make tea, and sit outside the tent to write in the last soft light, the trees on the far bank charcoal silhouettes. When I press the pen, a light comes on. As I write, the pen illuminates the page. She was telling me that the pen has a light in it.

Ah, the rational French, ‘you will write in the light.’

Day 10: Sully-sur-Loire to Sully-sur-Loire, 16 miles.

3am thoughts. The savage river dreams. Norse pirates. Theodulph’s oratory. The saint at the abbey. The Apocalypse. The first heretics burned at Orléans. Joan of Arc and visions. Max Jacob. The failure of la Méridienne verte, the success of letterboxes.

3 a.m. Writing, in the cold, unfamiliar light of my new, illuminating pen. The third time, recently, love struck me with the freshness and force, the spark of the first time we had set eyes on each other so many years before. Having lived our lives separately, differently in the years between, we arrived, just once, at the same time, the same place, the moment. Just once. Love struck.

And yet. How easy, at 3 a.m., alone in the shroud of my tent, with the faint whispering of the ever-flowing river, the occasional woodwind note of a night bird, a motorcycle accelerating across the bridge, the thrum as it crosses the end of the bridge onto the dead-straight road, heading north, or south, how easy for me to believe that I have got my life all wrong, that she, with investment in capital and family, with continuity and acceptance, had got it right, had chosen the responsible way. That I would be wrong to try (as I always try) to lead her away from the hearth, into the twilight world between fire and stars, between camp circle and forest. Rather, that I should forget myself and, amenable, slip into a place in that circle, fit in, warmed by the fire in front, with the firelight sparkling and enlivening the faces in the circle, the light and noise blanking out the solitude and silence behind …

And yet. We met after long and different lives, while living those different lives, drawn to each other eventually by their difference. Why this choice – either to join her circle, or to entice her out of it? Why not let be, so each can be themselves in their lives? Have faith in the compatibility of our unlikeness.

And remember my duty to the path I have chosen. ‘Breaking my staff’, ‘burying my book’, ‘abjuring rough magic’ etc., would be a betrayal of my life.

Perhaps, rather, it is time exactly to move forward, to deny myself all notions of ‘retirement’; to work more. The faith, once chosen, is an obligation.

I wake to a morning when I have no camp to break, no packing up to do, no destination to plan for. I have a day by the Loire. There are cycle paths the length of the river, over a hundred kilometres. Which way to go? Upstream, to the nineteenth-century technological marvel of the Briare aqueduct? Downstream, along the Loire of long history?

The thin man is leaving. I watched him arrive last night, leaning forward, looking neither left nor right, no eye contact, no word. All his movements are quick, impatient. Quickly, impatiently (how ‘things’ annoy him!) he rolls up his low dark tent, packs his few things into the coffin-like box on his bike. Quickly, impatiently he pushes his bike to the camp-site road, acknowledging no one. As if nothing, anywhere, is good enough, so he must move on. Or is there, just beyond that Concorde nose, that beard like the ram of a Greek trireme, that butting forehead, a destination, ever out of reach? He pushes off, cutting through like the bow of a ship, and the sea closes behind him, and he leaves no wake. An icebreaker, breaking a cold path through ice that freezes behind him. He’s gone.

I have become a mesh, through which some things pass, to which some things stick. Unsure any longer which is me. And not sure it matters.

I find the cycle path and head west, downstream, the path weaving sometimes alongside and sometimes away from the river. It is a bright, hazy day, very calm. The river flows slowly, slowed by the friction of its alluvium bed. Or perhaps reluctantly, as if there is too much to explore among the sandbars and vegetation-covered islets, the coves and beaches, too much of interest to hurry. It is a curious river, a nosy river, nosing here, nosing there.

And a dreamy river, on this low-water June day, in the bright, hazy light of a big sky.

No wonder Guillaume de Lorris had his dream here, dwelt here in the garden of his imagination, wrote the four thousand lines of his dream “in which the whole art of love is contained”.

No wonder the French kings and nobles who built their châteaux along this river built them ever up and out, elaborating them, with complication and embellishment, endlessly, as if in a dream.

And yet so much French history happened here.

Châteauneuf-du-Loire has echoes, but only that, of the heyday of navigation, before the railways were built: a chain suspension bridge like the fallen one of Sully, high enough for the sails of boats, stone quaysides now tidy and deserted, fine traders’ riverfront houses, a museum of river navigation. I might cycle on to Orléans, where so much has happened. Instead I turn around and cycle back towards Sully: I have two destinations, which I want to visit, in order, travelling back upstream, first to Germigny-des-Prés.

The first fortifications on the river were built to resist the Norsemen, who rowed up in the ninth and tenth centuries, out of curiosity, and in a quest for booty. This was before they settled in Northern France and became the Normans. One of the places they destroyed, in 860, at Germigny-des-Prés was the grand palace of Theodulph, religious advisor to Charlemagne, and bishop of Orléans.

All that survives is Theodulph’s oratory, consecrated in 806. From the outside it is a modest building, square, with half-circle apses on each side, tiled pitched roofs, small windows, a central tower. It is domestic in scale. Or rather, private. It is unassuming, with no sense of making a statement.

Inside it is made up of the simplest forms, of square and circle, pillar and round arch. And yet it has a great sense of unity, integrity, and intensity. Why is this?

The square is divided, by four pillars, into nine squares. And it rises up through three levels. It is, without being obviously so, a cube of nine. This evokes the celestial city as described in the Book of Revelation.

And the arches aren’t quite semicircles, but horseshoe-shaped, a form brought by Theodulph from his native Spain. As are the apses. And that slight pinching in, and the pattern of different-sized arches and slender pillars, ever changing as one moves, create tension, dynamism, even expectancy.

All the pattern and change swirls around an illuminated central stillness.

Under the tower is a simple, still, light-filled space, Turrell-like, where the white light is purified. This is the oratory, the private prayer space of the bishop.

His work, as spiritual head, depends on him intensifying the spirit within himself. This space is his spiritual accumulator. It is expressive of a vision of accumulation and intensification. Rather than, as I’ve met so often with the Gothic, of upreaching and aspiration. The light touches in benediction a bent head that is turned towards the inner light. Rather than shining in upraised eyes searching into the beyond.

From these forms, the Spanish and the Byzantine, influences from the south and east, developed what the French call Roman and we call Romanesque. It quickly became the standard church architecture, until the Gothic. And it expressed a different focus in Christianity.

And so that he is not lost in abstraction, facing the bishop in his oratory, in the dome of the eastern apse, is a gold-rich mosaic. It is the only Byzantine mosaic in France.

Traditionally it would have been of the Virgin, with the Christ child on her knee. But the oratory was constructed during a period of Iconoclasm, when such images were prohibited. So it represents the Ark of the Covenant. The ark contains the manna, which was regarded as prefiguring the Virgin, flanked by two cherubim and two smaller angels. Not to be worshipped, as Theodulph makes clear in his writings, but as an aid to contemplation.

But, and this is weird, what I see, when I look at the mosaic from a distance, is first an ark and angels, but then the face of a horned and bearded devil, Satan. First one, haloed and winged cherubim and angels. Then the other, halos become horns, wings and angels a brutish snout. It is so clear, it must be obvious. Has no one else seen this? What is going on? I leave, scratching my head.

A little upstream, at St-Benoit-sur-Loire is the Abbey of Fleury. Theodulph was abbot here.

In 630, monks from Orléans founded at Fleury one of the first Benedictine abbeys in Gaul. Benedict’s abbey at Monte Cassino had been laid waste by Lombards in 580 and abandoned. In 672, intrepid monks from Fleury walked to Monte Cassino, found Benedict’s remains, and brought them to Fleury, which became the primary centre from which Benedictine principles spread. Both the Cistercians and Cluniacs adopted the Rule of St Benedict:

This abbey is the root from which the monasticism of the eleventh century grew and flowered.

Benedict’s bones were interred in the crypt, the foundation stone placed upon him, and with him at its centre the church was built up from him. All rests on him, all converges on him, all grows from him.

In 1020 Abbot Gauzlin built a monumental tower here, “to serve as an example to the whole of Gaul”: it was an evocation, in architecture, of the celestial city, the new Jerusalem, as described in Chapter 21 of the Book of Revelation.

It is time, at this church 2km from the Green Meridian that was intended to commemorate the second millennium, to go back to the first Millennium, the year 1000.

Michelet writes: “It was the universal belief in the Middle Ages that the world was to come to an end in the year One Thousand AD.” People waited for the end. And when it didn’t come, “by the coming of the third year after the year 1000, churches and buildings nearly everywhere were again being built, especially in Italy and Gaul … It was as if the very world was shaking itself free of its decrepitude and everywhere put on a white mantle of churches.”

This is an often-quoted passage from the eleventh-century Benedictine monk and scholar, Rudolfus Glaber. More careful research has shown both these statements to be exaggerated, and that those predicting, and believing in the imminent end of the world were a minority. Albeit a noisy one. Abbon, the abbot of Fleury before Gauzlin, tells of having heard a preacher in Paris talking thus in the 950s, and that such ideas were circulating in the 970s. They faded as 1000AD passed.

But it clearly bothered Gauzlin enough to build his tower in 1020 (another favoured date for the apocalypse was 1033) “as an example to the whole of Gaul” of what can come after. For what follows the Apocalypse, and the defeat of Satan is, as John writes, “a new heaven and a new earth … the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God.”

And what survived 1000AD was a newly-persistent idea: millenarianism. Cohn, in The Pursuit of the Millennium, describes it as “a group’s belief in a terrestrial, imminent, total and miraculous change that results in salvation for the members of the group.” It was a commonplace when I worked in Watkins esoteric bookshop in the 1970s, from the Age of Aquarius, to the Mayan ‘End of Time’ of 2013.

It vibrates north up the Meridian to Paris and beyond in Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, south to the mystery of Rennes-le-Château and Pic de Bugarach.

It echoes in Utopianism, its post-religion, secular version.

It underlay my belief in ‘the new world’ that I would help to build as a socialistic town planner in the post-war welfare state consensus.

And when that fell apart, my embracing of a News from Nowhere ‘salvation’, that would come from a handwork-based life focussed on rural self-sufficiency.

Perhaps the Green Meridian was a last, faint echo.

Or maybe an example of revivalism that had no traction, that failed to ‘take’ …

Abbot Gauzlin’s Porch-Tower is his contribution to the millennium, and is still standing in front of the abbey.

It is a remarkable and very attractive building. The four pillars at the centre divide the space into nine squares, referencing Theodulph’s Oratory, and evoking the celestial city, the new Jerusalem, which “forms a square, its length and breadth and height being equal. It has twelve doors, three to the east, three to the north, three to the south, and three to the west, and they are never closed since this place knows neither day nor night …”

The capitals illustrate the Book of Revelation, with Christ in glory, the book with seven seals, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse, and more.

Thus, at the turning of the millennium, he gave hope. It echoes Theodulph’s Oratory, also a cube of nine. And, too, I can’t shake from my mind the image, in the Oratory, of the mosaic in which I saw both angels with the Ark, and a horned Satan. Who, in Revelation 20, is “let loose from his dungeon … to seduce the nations in the four quarters of the earth” …

For what arose at the same time as millenarianism was heresy. Or rather the idea of heresy. Which was, of course, the work of Satan.

Books have been written about the extent, even the existence of heresy in the period from 1000. I will look at this when I reach the Cathar lands. Enough to say that in 1022, just two years after he began his tower of the New Jerusalem, Gauzlin convicted 14 canons of Orléans cathedral of heresy, and had them burned alive. They were the first executions of heretics since Roman times.

After which I enter the church. It is a fine church, and I can imagine the life spiritual growing up, like stems from a root, from Benedict. Pillars sprout and arch in sprays of masonry up from his bones in the crypt, the upgushing of a spiritual fountain. And the church (The Church) rests upon the foundation of his bones

It was much visited by churchmen, including the pope, the king, and Bernard of Clairvaux in 1130. After the abbey was closed down in 1790, the church was saved by becoming a parish church. The monastic tradition was maintained by having a priest who was secretly a Benedictine monk (shades of Dan Brown!). In 1865 a group of monks came to maintain the presence near the saint. Full monastic life was restored in 1944. The monks perform the offices six times a day.

In this quiet space, I notice two plaques on the wall.

One records a visit here by the dauphin with Joan of Arc in June 1429, when Charles, seeing how tired Joan was, suggested she rest. To which Joan, in tears, replied that she would not rest until Charles was anointed king at Reims.

The Loire was the front line in the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), with the English army pouring south. Following defeat after defeat, the last French bastion on the north bank was Orléans. Joan, an illiterate peasant girl of seventeen, after visions of saints told her to drive out the English, had made her way from her home in Burgundy (allies of the English) to the dauphin at Chinon, got into his presence, and persuaded him to let her take part in the relief of Orléans. The breaking of the siege coincided with Joan’s arrival in the field, and was hailed as her triumph. It was the turning point of the war. Within two months she was at the dauphin’s side at his coronation at Reims. Thereafter she helped at the siege of Paris, but was captured when attacking the Burgundians at Compiègne. They sold her to the English.

The English, in their stronghold of Rouen, arranged for compliant French clergy to try her for heresy, declaring the visions diabolical and condemning her. She saved herself by recanting. So, the church required a second conviction. It found her guilty of cross-dressing (when in she only wore men’s clothes in circumstances that the church allowed, for example to deter rape). The records of the trial show that she handled herself with remarkable self-possession and acuity. She was burnt at the stake by the English, aged nineteen, her bones reduced to ashes and dumped in the river – or rather, dissolved in the very water of France. It is one of those stories beyond the power of invention.

But, what are visions?

Rationalist science treats them – has to – as delusions created by neural misfirings within the individual’s brain, products of sickness or overwrought imagination.

Religions, believing in the supernatural, need ways of dealing with visions, especially of separating the true from the false, those that lead us towards God, and those that lead us away, usually towards Satan.

Julian Jaynes writes of a critical change in human history, recorded around the eighth century BC, from a time before, when the gods were ever present, humans conversed with them, and held them responsible for their actions, to a time after, when the gods had absented themselves, leaving humans to make their own decisions. He sees this as the moment of the development of self-consciousness.

But Jaynes, as a scientist, saw these gods not as existing, but as the internalising of the humans’ authority relationships. Whereas I, although a non-believer, want to see it as the moment when we gave up on the gods, on the idea of gods, eventually turning the remnants of the direct experiencing of them into a disease called schizophrenia. And as the moment the gods, if not exactly giving up on us, stepped back, as if unsure of, not safe with, what humans had become.

The problem is that, as Harari makes clear, the differentiating characteristic of Homo sapiens is “their ability to transmit information about things that do not exist at all. As far as we know, only Sapiens can talk about entire kinds of entities that they have never seen, touched or smelled.” That is, imagination. Once this has happened, a species – us – has no way of determining what is ‘real’.

From this follow most of our achievements. And most of our insecurities. The sense of living in a world that is fruitfully malleable, in which perhaps anything is possible; but that is never stable, always questionable.

And where are gods in this? I find myself telling a friend, ‘I don’t believe in gods. But I would not want to live in a world where no one believed in gods.’

And this, from Traherne, “God hath made you able to create worlds in your own mind which are more precious to him than those which he created.”

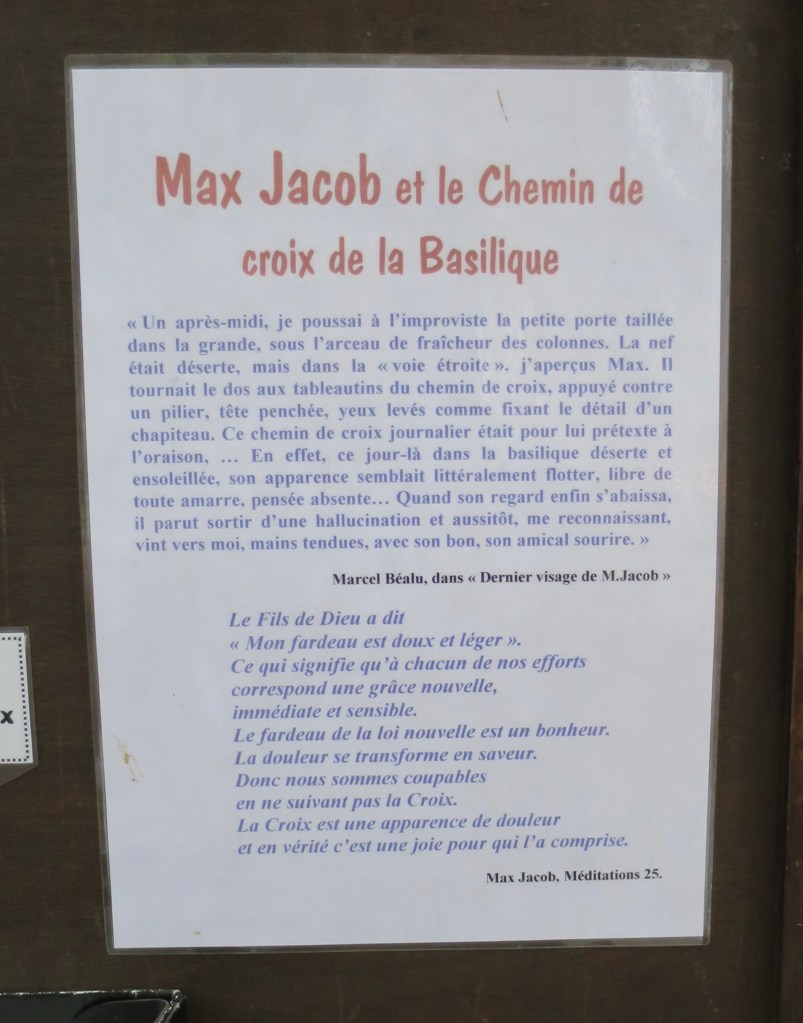

The other plaque is about Max Jacob. He was a writer who befriended Picasso when he first came to Paris, taught him French, introduced him to Apollinaire and Braque. A Jew, he had a vision of Christ in 1909, and converted to Catholicism. In Picasso’s ‘Three Musicians’ he is ‘the monk’. He spent much of the 1920s at St Benoit-sur-Loire, and lived here from 1936 until 1944. Marcel Béalu records entering the church and seeing Max, who was supposed to be studying the pictures of the Way of the Cross, “back turned to the pictures, leaning back against a pillar, head back, eyes looking up, as if fixed on the detail of a capital. His “study” was an excuse for prayer. He seemed literally to float, free of all moorings, without thought, absent … When at last he lowered his gaze, he seemed to come out of an hallucination, and immediately on seeing me, came towards me, hands held out, smiling his lovely, friendly smile.” In 1944 he was arrested here by the Germans, as a Jew, interned at Pithiviers. He died of pneumonia in Drancy before he could be transported to Auschwitz.

I come out of the monastery, out of history, into a light made luminous by the flowing waters of the river. The Loire is ‘Fleury’s golden valley’. Jacob wrote that here he was in the most beautiful countryside in the world, with the most perfect balance between three masses: of stone, of greenery, of water. For him, the Trinity. To which he added another mass – silence.

I meander east in the sunshine, between wide fields and shining river, past a meadow of brown goats, and find a marker for the Meridian, almost buried in midsummer vegetation. The banner talks of the trees planted along its length “establishing a strong relationship between new generations and the environment.” It leans, about to fall. And where are the trees? I’m by the river, at the point where the Meridian crosses the river. Invisibly.

How would different people mark the Meridian?

Grandville, who in 1844 represented the rings of Saturn as a “circular balcony on which the inhabitants of Saturn strolled in the evening to get a breath of fresh air” might have marked it with a carriage way of innumerable iron arches and cavalcades of coaches, north to south.

For 1960s architectural technical utopians, sons of Corbusier, it would be a linear city with a multi-lane motorway running along the top of the buildings.

Ecologists would have a green way, a protected corridor in which wildlife would live unhindered, and providing them with safe migration routes.

The technologically-inclined millennials would have fun with laser shows, waves of light and sound propelled along it.

Half a million people could link hands.

A shouted or a waved message would need just thirty people in each commune to take part, 10,000 in all.

Imagine a shouted or sung message sent along the Meridian.

Imagine a dance in each commune which at an agreed moment stops, and everyone joins hands and connects to the adjacent communes …

Or it could be an opportunity for each locality to find its own form of expression, to express its individuality, that it would share with other communities on Meridian Day, not exactly a competition, but an opportunity to show off …

And here, where the Meridian crosses the great central river of France, how I want an arc-en-ciel, a rainbow of connection across the water! But there’s nothing.

And yet, perhaps the days of such collective action are over. Even on demonstrations there is the sense of atomised individuals absorbed in recording and broadcasting their own experiencing. We are each, now, the star of our own show.

As if in illustration, 5km from here is the village of Saint-Martin-d’Abbat. In 1997 someone proposed that householders customise their letterboxes. (The French, like Americans, have letterboxes at the edge of their property.) Now there over 200 decorated boxes in the village. It was an idea that ‘took’. They variously depict a cow, a dancing couple, a tractor, a fire-hose reel, a guitar, a public telephone box, all sorts. Each is the expression of an individual nature and interest. Like the passerelles at Amiens. And like the passerelles, they are at the limes of the home, the place where the private pagus meets the public realm. Not nationality or locality, but individuality. Not la patrie or le pays, but la personne. “Since 1789, the entire nation, as a people, has unfolded in the purified individual.” (Hugo.) And, however much I may wish it different in others, it is how I have lived my life. Time for dinner.

I eat in my Chinese takeaway. As I begin to eat, prawns instead of chicken tonight, the young assistant approaches shyly and asks if I left a pen here last night, holding out to me my cheap bic. I am touched. I have two pens again. And each, now, resonant with generosity.

Notes:

Guillaume de Lorris wrote the first part of Le Roman de la Rose, which I write about on Day 9.

Day 11: Sully-sur-Loire to Bourges, 62 miles.

Hunting grounds of Sologne. Celtic nemetons. Meaulnes’ lost domain. Alain-Fournier’s birthplace. The closed museum. The first moped. A French ‘Passport to Pimlico’. ‘Êtes-vous pèlerin?’

A sunny day. As I cycle out of the campsite, I wave to the woman at the desk. She raises her hand and smiles. A different sign, signal to each person, an expression of what she has taken from each, an acknowledging smile, the world experienced from her desk.

Heading south, I am soon in the Sologne. What a change! From dreaming river, wide hazy fields, carefully-wrought stone crucibles of the soul, I am in a forest.

And such a forest!

Of turbulent growth, rampant and multifarious greenery, unrestrained vegetable energy, a bursting up, bursting out, with dense trees swathed in vines and buried in thick undergrowth. And a place of wild animal energy, of snorting combative well-being, the grunting, headlong boar, the crashing bellowing stag. Nature let go, left free to its burgeoning, energetic competitiveness. A place not to tame but to fight; not to coerce but to do battle with: a place for man, his ancient blood up, to hunt.

In Celtic times this uncrossable forest marked the boundary between two of the great tribes, the Carnutes, whose capital was Orléans, and the Bituriges, centred on Bourges. It is reputed to be the location of one of the great Celtic nemetons, the sacred groves where druidic rituals were shared between the tribes.

The sort of place that Lucan titillatingly described thus. “No bird nested in the nemeton, nor did any animal lurk nearby; the leaves constantly shivered though no breeze stirred. Altars stood in its midst, and the images of the gods. Every tree was stained in sacrificial blood. The very earth groaned, dead yews revived; unconsumed trees were surrounded with flame, and huge serpents twined round the oaks. The people feared to approach the grove, and even the priest would not walk there at midday or midnight lest he should then meet the divine guardian. At a certain season the druids assemble in a consecrated place on the frontier of the territory of the Carnutes which is taken as the centre of all Gaul.”

And it is the heart of Robb’s Celtic wisdom, a wisdom buried first by the mechanistic Romans, and then by the Christianising Franks. The root of a Gaul that has lived on in the French paysan soul.

Developed as aristocratic hunting grounds in the fifteenth century, the Sologne became neglected, its impermeable soil making drainage difficult, so that by the nineteenth century it had become a “dreary, bare, lake-studded plateau … with its malarious, scrofulous, wretched inhabitants.” (Ormsby). A traveller records in 1863 “a desolate country, crossed by a difficult, sandy, deserted road; not a single château, farm or village in the distance, just a few lonely, wretched hovels.” Such a contrast to the château- and trade-rich Loire valley, the managed Forest of Orléans just to the north! I realise that crossing the Loire I have passed out of the direct influence of Paris (which is only 60 miles north of Orléans), and taken a step deeper into la France profonde.

The area was transformed by Emperor Louis-Napoleon from the 1860s, by drainage and afforestation. A personal interest because his mother’s family, the Beauharnais, lived here. Much of it was then bought up by the new belle époque wealthy for hunting estates.

Hunting, the great aristocratic privilege, had been opened to all at the Revolution, to great rejoicing. And the first day of the hunting season is still celebrated with expeditions and fusillades across the country. I remember being woken by the blaze of gunfire all around our cottage in rural Aveyron, and the neighbour’s son triumphantly returning with a rabbit slung over his shoulder. They shot songbirds and dropped them in the freezer one by one until they had enough for a meal. But by 1820s restrictions were being introduced, hunting was increasingly privatised, and these hunting estates are the result.

Which is how it is today. There are a few signs of agriculture. Here and there a field has been cleared of forest for a crop of hay. Here a bog, there a lake among the trees. There are occasional houses, but behind high walls, buried in trees. There are tracks leading into the forest, but everywhere the signs, ‘no fishing’, ‘no entry’, ‘private’, ‘keep out’.

I find a Meridian marker, and a road running south, on the Meridian.

I have just passed 500 miles on my milometer. I stand on the white line, photograph its recession to the vanishing point between the trees, imagine it across France to the Pyrenees.

By the road are rough platforms. I imagine them to be the platforms that the original surveyors built, where they took their readings and made their meticulous notes. But they are for the guns (the instrument becomes the man) to shoot from.

In my ride along empty lanes through the forest I come upon villages buried among the turbulent vegetation and hacked-out farm land. A house in this village has long ladders fixed diagonally across its walls as decoration. On a gate in this one is a handwritten sign, ‘Ste-Montaine in peril. No to the quarry.’ There are apple trees and pear trees and vines. A length of road has an avenue of large trees cut down, tree after tree. They lie like fallen idols, or gods, the resinous smell is of their ichor.

It is a place to explore, get lost in, to follow intriguing tracks leading off into the woodland. But every one has a sign, sign after sign, ‘no entry’, ‘private’, ‘keep out’. A privatised realm, enforced by the powerful.

But it is exactly in these unmade roads winding into the forest, the buildings glimpsed through the trees, the secret worlds at the ends of tracks, that my interest lies. For this is the world of the ‘lost domain’ of Le Grand Meaulnes. I am, at last, in Alain-Fournier’s Sologne.

Le Grand Meaulnes was Alain-Fournier’s only novel. He was killed, age 27, in the second month of the Great War. For the French the book represents the world lost in that cataclysm: not just the old world, but the young men, and the possible futures. It fixes the moment after which nothing was the same again. It is a school set-text.

For myself, and fellow discoverers, it is one of those books that, if it catches you at that right moment, when you are young enough to crave adventure, old enough to be romantic, it keeps hold of you. You find your hand straying to it late at night, and you reread it, alone in the night, in the light of a single reading-lamp, your home, wife, family, life all around you out there in the dark beyond the lamplight, and you shake your head and smile, and go deeper each time into its labyrinth of friendship, love, loss, yearning, acceptance, while gazing often out into the dark.

I turn south east, out of the Sologne, towards the birthplace of Alain-Fournier at La Chapelle-d’Angillon.

Looking at the map, I see that a few miles north (past La Surprise, yet another intriguing name on the map I won’t visit) is Aubigny-sur-Nère. A ‘Franco-Scottish’ festival is held on Bastille Day. The ‘Auld Alliance’ between France and Scotland is traced back to 882. It is an area where, according to Robb, Scottish veterans from the Hundred Years War were settled. I wonder if my bagpipe-playing friend is of the same clan. So many places passed, unvisited, on this trip, because of the discipline of the Meridian.

La Chapelle-d’Angillon in the midday sun, hot now, is deserted. Doors and shutters are closed, there is no sign of a shop. Just a bar, long closed, now a house that has kept the fading sign, ‘café A.Mercier, bar’.

Fournier’s father was the schoolteacher here until Henri (as Alain was christened) was five, when they were moved to Epineuil-le-Fleuriel, in the south of the département. His parents returned to teach here when Alain was eighteen, when he was at school in Paris. And they were still here in 1914, when he died.

The place of his birth, 35 Avenue Alain-Fournier, is a neat house that must have been new in the 1890s, a child’s picture of a house, with a pitched roof, two windows for eyes upstairs, and a door like a surprised exclamation. It even has an ivy nose.

But all the shutters are unpainted and rusted shut, and the garden is overgrown, with unpruned white roses and red camellia climbing the front. On the gate-post there is an enamel sign, ‘Member of the Federation of writers’ houses, and the literary heritage.’ Patrimoines littéraires meaning so much more in French, and to the French, expressing both national identity and uniqueness. French exceptionalism again.

I cycle past the locked mairie, along a street emptied of all life (not a cat, not a bird), sharp angles of light and shadow, to a mural covering the side of a house. It is a feature of French towns and villages, this painting of large, descriptive murals on the rendered end-walls of houses.

This one depicts ‘La Chapelle’s medieval fortifications’.

Next to it is a board telling of a Greek hermit who settled by the river here, among the beehives that belonged to Bourges abbey. After his death in 865, the faithful came to pray at his tomb, Monks from Bourges built a chapel for the pilgrims (for prayer, and to collect donations). La Chapelle passed to Gilon of Sully. He was a descendant of the Vikings who had rowed up the Loire in the ninth century and sacked Theodulph’s palace. In 1064 Gilon gave the monks the right to glean in the forests, fish in the streams, and cut enough wood to build a new priory. He also fortified the village, and built the château. The archbishop who built the great gothic cathedral of Bourges came from here.

But my priority is Alain-Fournier. There is a museum dedicated to him at the château. And I have questions to ask. While the geography of the book, the towns and villages mentioned and the area he gets lost in, ‘in the whole of the Sologne it would have been hard to find a more desolate spot’, clearly refer to this area, equally clearly the house, school, and the village he wrote about bear no resemblance to what is here. I’m hoping the museum will unpick the story. I head for the château.

The museum is in a neat brick building, ‘Musée Alain-Fournier Jacques Rivière’ (Rivière was the close school friend who married his sister), in smart art-nouveau lettering. ‘Ouvert 14h à 18h’. It is 15h, and very fermé. It is as shuttered as his birthplace.

The château is a tall, four-square building, a keep, set in a deep moat. It has round towers with conical roofs either side of the front door. I cross the drawbridge. On the door, in French, ‘Welcome! To the ancient sovereign principality of Boisbelle. To visit please ring the bell.’

I yank the ancient bell pull. The bell clangs sonorously. I wait for slow steps on stone, the creaking of rusty hinges, the dusty retainer. Or even the ‘sovereign principal’ himself. But no one comes. Many of the windows are broken, and it all looks rather dilapidated.

But when I walk round the back, there is a large visitor car park, carefully laid out, with signs ‘do not drive on the grass’. Completely empty. The place has been arranged as a major tourist attraction, but is quite deserted. Perhaps a case of ‘build it and they will come’, but they came not? Or perhaps a place that only comes to life in the two months of French holidays.

Past the car park it opens out into a deer park, with a lake and a splendid giant cypress tree. At the back of the château, overlooking the moat and the park, and facing the sun, there are well-maintained brick buildings around an attractive courtyard, with flower beds, statues and several modern, expensive cars. Signs of a comfortable life. But no one.

I head out of the village, having seen no one, and found no answer to the mystery of Meaulnes’ ‘lost domain’. I head out on a minor road towards Bourges, to avoid the dead-straight D940.

Through the village of Ivoy-le-Pré. This is the birthplace of Felix Millet, who invented a rotary engine that in 1892 he attached to the back wheel of a bicycle, creating the first moped. It was the progenitor of France’s universal Solexes, eight million of which were made. The very image for adolescent us (still on push bikes) of young France. With a ‘cool’ quotient (especially when a slender girl with flying hair was bouncing along on it) the moped could never match.

A failure in the 1895 Bordeaux–Paris–Bordeaux motor race ended its commercial life. “By 1900 the Millet marque had disappeared.”

But the engine had a second life as an aircraft engine in the first World War, and many planes were powered by it.

How did a man from a village in the middle of nowhere, at a time when the bicycle was a novelty, and in the earliest days of internal combustion engines, come up with such an idea, build a prototype, and develop it on a commercial scale? I guess he was the equivalent, in his day, of today’s kids who develop killer apps in their bedrooms.

In Ivoy is yet another renovated washhouse. On it a sign: ‘Contes et légendes de nos lavoirs en pays Sancerre Sologne’, and the tale of a grumpy, plough-throwing, bachelor giant.

The Principality of Boisbelle, I discover, was a kingdom within the kingdom of France. An independent realm in which the Prince of Boisbelle had sovereign rights, to make laws, administer justice, and mint money, and where the inhabitants paid no taxes. They were exempt from the hated gabelle (salt tax) and the equally hated corvée (the duty to provide their labour for road upkeep), paying dues only to the church. And they were exempt from military service. This utopia was established by the descendants of Viking pirates, and the privileges were repeatedly renewed until 1766.

This curiosity was, curiously, bought in 1605 by Maximilien de Béthune, first Duke of Sully, Henry IV’s chief minister, when his main base was at Sully-sur-Loire. Curiously, because Sully’s main achievement was in unifying and centralising the French state.

But he was a devout Protestant. (As was Henry, but he had converted on becoming king, to stop the ruinous forty-year wars of religion.)

In 1609 Sully began to build, in the middle of Boisbelle, 10km from La Chapelle-d’Angillon, a new town, dedicated to Henry, called Henrichemont. He designed it as a square within a square, with geometrically radiating roads. It represented an ideal harmony. It had its own money, its own mint. What was his idea?

To provide a refuge, in this state within a state, for Protestants, who were still persecuted in spite of the Edict of Nantes of 1598? Was he, in this, secretly encouraged by Henry? It did indeed become a refuge for persecuted Protestants.

Or was it, rather, the blueprint, with its geometrical harmony, for a harmony between Catholics and Protestants? It was, after all, planned to have both Catholic and Protestant churches.

Was it to be the capital of this state within a state, where Sully could, in small, work out ideas that he might then apply to France as a whole?

Who knows what might have happened here, what example might have been set? But this is my imperturbable faith in utopian thinking. Whatever, in 1610, a year after Sully began building his new town, Henry was assassinated. Within months, Sully had fallen from power. In 1685, after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes began the renewed active persecution of Protestants, the Protestants left the town.

The Henrichemont I cycle through is an ordinary small French town, its high concepts neglected, its ideal proportions blurred, obscured by time, practicality, and forgetting.

In 1766 Sully’s descendant gave up the Principality to the crown, and it lost all its privileges. Although you can still buy its coins in the collectors’ market.

What was a candidate for a French version of Passport to Pimlico had become a might-have-been.

Although that doesn’t stop me, as I cycle along the quiet roads under shading trees, writing the script. It would involve the eccentric but canny aristocrat of La Chapelle, his feisty daughter, the radical schoolteacher, the tax-avoiding, smuggler-peasants, the recently-arrived eco-activists, the at-first scandalised, but then gleefully complicit priest, in an unlikely alliance of utopians …

I pass the villages of Presly, Pigny and Fussy, who become, on a long slow climb (oh for Millet’s startling, rotating engine!), a trio of loveable, hairy dwarves forever playing tricks on grumpy, plough-throwing giants. Such japes!

At the top of the hill I have my first view of Bourges, its great cathedral almost celestial in the late afternoon light, a shimmering destination for devout pilgrims.

‘Êtes-vous pèlerin?’ The girl on reception at the youth hostel in Bourges asks casually. A pilgrim, me …?

‘Sorry?’

‘Are you on the Camino?’

Bourges is on one of the routes to Santiago de Compostela in north-west Spain. Do many pilgrims stop here? I ask. Yes, many, she says.

The relics of St James became a popular pilgrimage destination after the ‘discovery’ of his bones at Compostela in the ninth century. It is glib, but not without a germ of truth, to see our holidays as echoes of medieval holy days, and tourism our pilgrimage.

For don’t we holiday for ‘re-creation’, to recover our lost selves, to come face to face with our true selves?

Don’t we often return from our holidays determined to change our lives?

And with the growth of adventure holidays, extreme experiences, cultural tourism, aren’t holidays becoming more pilgrimage-like, our substitutes in an age of unbelief for the journey of spiritual significance?

There has been an enormous increase in recent years in pilgrims to Compostela, whether believers or not. Am I a pilgrim?

In his 1140 guide to the Camino, Pope Callixtus II writes: “The pilgrim route is a very good thing, but it is narrow. For the road which leads to life is narrow … it is the thwarting of the body, the increase of virtues, the road of righteousness, love of the saints … it makes gluttonous fatness vanish, constrains the appetites of the flesh … cleanses the spirit, leads us to contemplation.”

And my journey?

The road is narrow, certainly, but I allow myself a capricious latitude from it.

It is less a thwarting than an exercising of the body.

I have sought out the shrines of my saints; but are they saints in any meaningful way?

Gluttonous fatness is certainly vanishing, as are the appetites of the flesh; but I welcome their absence because it increases my sense of well-being, rather than experiencing it as penance.

My life has simplified, and I am thinking a lot. Is that a cleansed spirit and contemplation? Or just mental meandering?

Doesn’t the personally-determined nature of my journey damn it as self-indulgent, a self-selected piece of cultural tourism?

And isn’t that just a fancy name for a holiday with pretensions?

And am I not just wheeling over the surface of ‘le Spectacle’, that simulacrum of reality created by consumer capitalism? And less ‘experiencing’ it than recording it, with notebook, tablet, phone, camera? To what purpose?

‘Êtes-vous pèlerin?’

‘No,’ I reply. But, still, I’m not sure.

Day 12: Bourges to Vallon-en-Sully, 68 miles.

The ambassador. Wild music from the cathedral. The pizza-man. Jacques Coeur and alchemy. The gnomon. Saint Sulpice and the Rose Line. Zone of Occupation. The many centres of France. ‘The Martyrs of Vingré’. Dinner beside the canal. Evening thoughts.

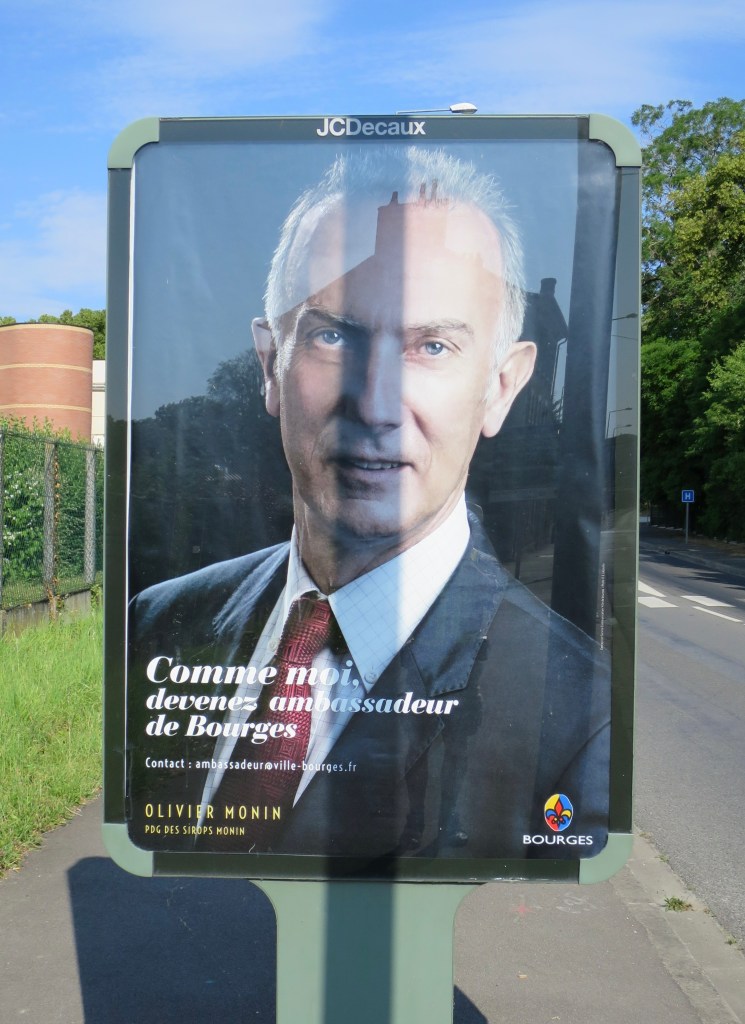

Cycling out of Bourges, towards the Meridian, which passes 2km west of the cathedral, I come upon a poster that sums up my problem with the city. It says, ‘Like me, become an ambassador for Bourges.’

The photograph is of a man in his sixties. But the modern, slim, healthy, prime-of-life sixties, white hair cut en brosse (to express vigour), direct gaze of penetrating eyes that engage and yet are slightly elevated, as if he sees beyond. A serious face, but with a slight crinkling of the eyebrows to show that he hasn’t quite solved all life’s problems, he accepts that life can be a funny old thing, but that, whatever comes up, you can trust him to be on top of it. In a dark suit, a restrained silk tie, a formal shirt that yet has a fine check and button-down collar. It is a calculated photograph, carefully calibrated. It is a political photograph.

Seeing it, I am reminded of Roland Barthes’ essay ‘Electoral Photogeny’. In such a photograph, the man’s effigy both elevates and distances him, while at the same time establishing a complicity with the viewer – this is a man you can trust to act in your best interests (even if you haven’t realised they are your best interests), who will apply his best efforts (so much superior to yours) to ‘being an ambassador’, and by so doing, both relieve you, and strip you, of – engagement. All contradiction is resolved. ‘All this coexists peacefully in that thoughtful gaze, nobly fixed on the hidden interests of Order,’ concludes Barthes. The photograph mediates. And this is a city that feels so well-ordered, smilingly opaque, that it feels all mediated.

But perhaps, arriving late, and leaving early, I haven’t given it a chance, now that I’m leaving … To return to my arrival yesterday.

The atmosphere has been building all afternoon, and it is hot and heavy, close, when I arrive around 5pm. I cycle past a fine trompe l’oeil scene on the side of a house, depicting an idealised medieval town centre, looking so three-dimensional that I can imagine riding into its quirkiness.

But the city centre itself is anything but quirky. It is foursquare and steady, solidly prosperous, and without such jeux d’esprit, such off-centredness, oddly flat. Even a fine medieval carved-wood facade looks over-finished.

From the bruised gloom bursts a short, large-dropped shower that wets and adds to the humidity, without clearing the air.

They are smilingly pleasant in the tourist office. But I am finding this a hard place to like.

It is similar to Amiens in its layout, with citadel and cathedral on high ground at the centre, and river and marshes (now recuperated for recreation) to the north. But whereas Amiens felt open, lively, and rather ramshackle, Bourges feels prosperous but ponderous, smiling but stolid, solid but dull.

Perhaps it’s my mood, but the great cathedral also strikes me as ponderous and dull. It is the most southerly of the ring of Gothic cathedrals around Paris, and was modelled on Notre Dame. But, without transepts, with five aisles, and very little light from the apse, it is dark and uninspiring, a dark barn, a retail shed of religion.

And outside, even the fine array of flying buttresses looks more like careful engineering than daring-made-stone. Is it simply the lack of the visual excitement created by Amiens’ water-spout gargoyles, the buttresses-upon-buttresses of Beauvais? Maybe here they were cleverer builders than at Beauvais? And they didn’t need Amiens’ waterspouts because it’s drier here? But they could have come up with something! This a place built within bounds, there is no risk, no inspiration, no aspiration. Light is excluded, and the stone weighs heavy. And heavy with symmetry and thudding symbolism – five aisles, five radiating chapels, five doors in the West front, to represent the five wounds of Christ. Even the highly-decorated West front looks fussy, grandiloquent rather than grand. Sorry, Bourges.

Disappointed, unsettled, I head for the youth hostel. Which is another disappointment. It is a grudging place, run more for their than the travellers’ benefit. The way to judge a youth hostel is by its breakfasts. I will see tomorrow.

I go out to find food. I walk past the West front of the cathedral in the evening light.

From inside, from behind the ‘frozen music’ of detailed carving, comes actual music: a thrilling, crazed combination of bagpipes and organ, the bagpipes piercing and keening, the organ thundering solid masses of spectacular chords.

What mad goings-on inside, the organist freed from liturgies in a clashing, harmonising battle with his virtuoso bagpipe-playing friend (perhaps Michael Aye himself)? Imagine the delight on their faces!

What must it be like inside, the cathedral unlit, a couple of candles creating strange, trembling shadows, the vast dark, the rumbling in the blood in each of them, the contrasting notes from the two instruments vibrating every surface …? I try the door. It is locked.

Walking back across a car park of fiercely-pollarded plane trees, a pizza van is open for business.

But no ordinary pizza van.

In the back, behind the serving hatch, is a large, open oven burning red with logs. The pizza man takes the order (from a list of twenty or more), and chatting the while to the customer, takes a piece of dough, passes it quickly first this way then that way through a mangle to produce a paper-thin base, then with rapid sweeps he coats it with tomato and grated cheese, and the pieces of chicken, tomato, pepperoni, prawns, mushrooms, whatever, to make up the ordered pizza. All this done with quick, precise movements while he engages with the customer.

He slides a flat wooden shovel under the pizza and pushes it into the furnace, to the edge of the burning logs. Surely it will burn?

No, with practised dexterity and skill – this man is an artist! – he manoeuvres it round four times with his paddle at exactly the right moment, so it cooks in from each edge. Then he pulls it out, places it in the box that he has in the meantime made up from a flat sheet of cardboard, labels it, passes it across, already turning to the next customer.

I open my box. The pizza is burnt at the edges, but a flavoursome burntness. And it is cooked through to the middle. It is a superb pizza. He is a master artisan, a practical genius. How I admire hand skills!

And he’s also a salesman. I note how he engages each person who comes to the van, to hold us no matter how busy he is, to get us in the queue, where we quickly become an intrigued audience. And the way he begins the next pizza while this one is in the oven, turning from his preparations just in time – quick! we want to shout, it’s about to burn! – to turn it deftly through another ninety degrees, a constant banter and by-play, perpetually working.

I sit on a wall, admiring a craftsman at work, and eat with relish, with a beer. A fine pizza, and crazy music – surely enough to beguile me? But I return to the empty, disappointing hostel, looking forward to leaving this disappointing city.

And yet in the night, these thoughts about Bourges.

It has been an important centre since Celtic times: it was the capital of the Bituriges, and it was the one Celtic city Vercingetorix could not bring himself to destroy in his scorched-earth policy in his war with the Romans.

It is almost at the centre of France. It is surrounded by rich farm land. It has, or had, my 1931 Geography tells me, ‘remarkable nodality’, with six main railway lines, and a dozen major roads radiating from it, as well as commanding important east-west and north-south routes.

And it is on or near several of the lines that divide France.

The line, from Biarritz to Strasbourg, that divides Highland France from Lowland France.

The language division that curves up from the mouth of the Gironde estuary to just south of Bourges separating oc south from oïl north.

The St-Malo–Genevaline, that has long been taken to mark the division between the ‘mature’ North, and the ‘undeveloped’ South, where the people were supposedly less literate, smaller, shorter-lived, more criminal, with a more backward agriculture, and in general less enterprising. (Amazing how a stereotype developed with the North’s victory in the Albigensian crusade, has been perpetuated for 800 years!)

It is at the southern edge of the reach of the scholastic Île-de-France.

And on the northern border of lively Aquitaine, home of the troubadours. It is on many lines of division. It could, thereby, be the great unifier. The place where difference meets, connects.

It should be the capital of France!

Indeed it was here that Louis VII, king of the Franks, unified North and South when he married Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1137. He was crowned in Bourges cathedral. But when he divorced her – against the advice of his wise counsellor, Abbot Suger – her subsequent marriage to Henry II of England precipitated 300 years of war.

No, France will always be centred on Paris. Bourges, for all its centrality, will always be peripheral.

Bourges’ most famous son is Jacques Coeur (1395–1456). At the time of Joan of Arc he founded a business empire, based on trade with the Levant, that made him within a few years the richest man in France. His money enabled Charles VII to push the English out of Normandy. He built a spectacular palace in Bourges. He was a confidant of the king, and reformed the mint for him. The Celtic ‘Bituriges’ means Kings of the World: Jacques Coeur was an early Master of the Universe.

But his wealth was his downfall. He had taken too much trade from other merchants, and lent money to too many nobles who didn’t want to repay him, and therefore had an interest in bringing him down. He was found guilty of trumped-up charges of treason, and his enormous wealth was distributed among the king’s allies. He never got to live in his new palace. The man on the poster, the Ambassador for Bourges, would approve Coeur’s entrepreneurship, but shake his head at his lack of understanding of tall poppy syndrome: one must get on, but be clubbable, Bourges-style.

Hardly of interest to me, the story of a man obsessed with building a financial empire. Even his opulent high-Gothic palace looks like overblown Gothic-revival.

Except that there was talk that he was an alchemist, literally ‘making money’. This was stated as fact in Fulcanelli’s seminal Mystery of the Cathedrals. And esoteric images have been found in the decorations of his palace. He was in Syria in 1432, and made his money trading with the Arab world. And ‘alchemy’ is an Arabic word. (From which chemistry developed. “But if you look at the history, modern chemistry only starts coming in to replace alchemy around the same time capitalism really gets going. Strange, eh? What do you make of that?” (Pynchon). A thought for another day.) But the true aim of alchemy is the transmutation of the self.

Meanwhile, there is the gnomon in the cathedral.

This is a narrow brass strip let, on a north-south line, into the nave floor. The sun shines, through a small hole made in a stained-glass window, onto this line every day at midday. Its position on the length of the gnomon tells which day of the year it is. It was used to determine Easter.

This reminds me of the gnomon in Saint-Sulpice in Paris, which Dan Brown, in his hectic holy-grail thriller The Da Vinci Code says is ‘built over the ruins of an ancient [Celtic?] temple to the Goddess Isis’. He says it is on the Rose Line. Okay, he conflates it with the Paris Meridian, which in fact is several hundred yards to the east. But parts of Bourges are on the Paris Meridian. And Saint Roselin’s (Rose line) day is 17 January. Saint Sulpice was bishop of Bourges and died here in 647. And his day is – 17 January. He was buried at a monastery near Bourges, and his tomb soon became a place of miracles. What if the monastery, and tomb are on the Meridian …?

The idea of making a hole in a stained-glass window to allow in a ray of light brings to mind Leonard Cohen’s ‘there’s a crack in everything; it’s how the light gets in.’ The idea that the ‘real’ light is too bright for us to endure, that material and conceptual reality exist to filter and ‘colour’ it, so we are able to live in a sensory world.

And how well that hole in the many-coloured narrative of the stained-glass window, letting in the pure light, illustrates it! Moments of sudden insight give us apprehensions of it, the light beyond light.