Day 1: Calais to Dunkirk, 38 miles.

A rainy Sunday. The old-timer. ‘The Jungle’. An Island Race. The Celtic Meridian. Barthes on plastic. De Tocqueville and French exceptionalism. The ‘Miracle of Dunkirk’. The first Méridienne verte marker. Grace at the Libanais take-away.

As the bow doors creak open, I prepare for the young man next me, who’s been revving the engine of his black Range Rover impatiently, to speed past me onto the ramp. Instead he looks across, smiles, and waves me on before him, with a courteous gesture. I acknowledge with a smile and a gesture I hope equally courteous – thank you, but do please go ahead. I follow him, freewheeling my heavily-laden bike down the steep, wet ramp, as the enormous lorries thunder past me.

It is a grey day in Calais, with rain sweeping across. There’s a strong southwester, and Dunkirk, tonight’s destination, where my journey begins, is to the north east. But first I’m heading to Sangatte, south, along the coast.

Through the centre of Calais, past the splendid Flemish-Renaissance-Revival town hall, across the Place d’Armes, the open market square, which today is a windswept, empty and bleak place, made more so by contemporary ‘art interventions’: fountains that wee weakly, and a grey sculpture of a grey couple huddled against wind and rain, altogether too literal.

It is Sunday afternoon, there are glass-fronted restaurants like aquaria all around the square, and in them the diners bob gently, in after-lunch repletion and vacancy, digesting.

I turn south, along the coast, into the wind, towards Sangatte, the Tunnel entrance. Past a water-tower decorated to commemorate Blériot’s flight across the Channel. Past the colourful bungalows of second-homers and retirees, safe behind grass-planted sand dunes, as old-fashioned as Newhaven. And then nothing but dunes. I had expected fences, and black and brown faces staring unblinkingly through. But of course the Sangatte camp was closed years ago.

So I turn around, and I’m flying back up the cycle path by the coast road, caped against the rain, when I see a cyclist bent over his bike. I stop, ask him in French what’s the problem. He replies in English. He’s Belgian. His problem is with the dynamo built into the front hub that charges his smart phone. I look at all the complication of disc brakes, of gears operated by brake levers (he has 27 gears, I have 10), of nine-sprocket cassettes (we called them blocks), and of cleated pedals (I still have toe clips and straps), and realise that this is all beyond me, incomprehensible technology. And that I am on a sixty-year-old frame, with nothing that wasn’t around seventy years ago. In my zip-up jacket, baggy cotton trousers, tweed cap, and voluminous rain cape, I am from a former era.

Tim Hilton, art critic and lifelong cyclist, writes, ‘Another cycling legend concerns the old-timer. In song and story he is not awheel but is encountered by the side of a road. He wears unfashionable clothes, carefully washed and stitched where necessary. He is not the sort of person who takes his rest in a haystack. He might be a ghost. The old-timer’s bike is ancient. Some of its accessories, in this story usually the mudguards, are held to the frame by twisted pieces of wire. But the transmission – chainset, chain and back sprocket, the heart of a bicycle – is expertly and beautifully maintained. The old-timer has climbed off to eat his sandwiches or to smoke a pipe. Other cyclists instinctively brake and stop to say a word in fellowship or homage. He replies only with the words, “it’s a grand life”. Just as no one has seen him ride, nobody knows where he comes from.’

I met him once, outside Chepstow, when I was young, before I’d read about him. Now I have become him. I have become the old-timer.

Back into Calais, and I have a problem finding directions to Dunkirk – the official signs are either to local services and businesses, or to motorways. Perhaps it’s a French thing, having two scales, the jealously-guarded local, and the centrally-imposed national. Whereas in England the signage is hierarchical, through levels. Reflecting our careful gradations of class?

I follow yet another sign to Dunkirk, which takes me, along roads lined with parked lorries, miles of them, of every European state, yet again to a motorway. Under it, there is a squatter camp.

This is ‘The Jungle’, the camp that grew up after Sangatte was closed. Black and brown faces looking through the fence, patiently waiting, eyes ever watchful for that opportunity, the single chance (an unlocked car boot, the back of a freezer lorry, under a railway carriage, even walking the thirty miles – around fifteen die each year) that will get them through the Tunnel, across the Channel, to England. Having crossed continents, passed through EU countries, still they want to cross the narrow strip of water, put it between themselves and where they have escaped from.

The narrow strip of water that has always been for the English the symbol as well as the practical guarantor of their separateness. An island race, on a sceptred isle. What is to the French descriptive, la Manche, ‘the sleeve’, is for the English possessive, the English Channel. At times of weakness, they (we) are the plucky underdogs, on the ramparts of Shakespeare’s ‘white-faced shore’, and ‘water-walled bulwark’, who face and outface overwhelming odds. In the time of Imperial greatness, they (we) had the arrogant condescension of ‘Fog in the Channel – Continent isolated’. But now we are in Europe.

Seeing the collection of small tents, the shelters improvised with plastic sheeting, figures squatting down in mud in the rain, or walking patiently to and from the Tunnel entrance, having done or about to do their shift of waiting their chance, I see figures walking out of Africa, as they have for tens, hundreds of thousands of years, Africa the origin of sapiens, a forever bubbling spring. And I see a world of increasing inequality but reducing friction of distance, so that more poor people know about, and are desperate to reach, and can actually reach, the gates of what to them is the golden city. Making the gate stronger, building the walls higher, guarding more vigilantly won’t work for long. The solution has to be to reduce inequality. It’s physics.

I eventually find my way out, under grey skies, pushed along by the wind at my back, across land flat as Flanders, with canals, dykes, and pasture, through Gravelines to Loon-Plage.

It was once the island of Lugdunum, ‘which means “fortress of Lug”, the Celtic god of light’, and is, according to Graham Robb, the northernmost point of the Gaulish or Celtic Meridian of mid-longitude, their equivalent of the Paris Meridian, which lies 10km to the east. The Celtic Meridian will haunt, flicker in the background of my journey down the Paris Meridian, the echo, the trace, the mysterious, the barely-remembered predecessor to Rationalism’s boldly stepped and clearly recorded line.

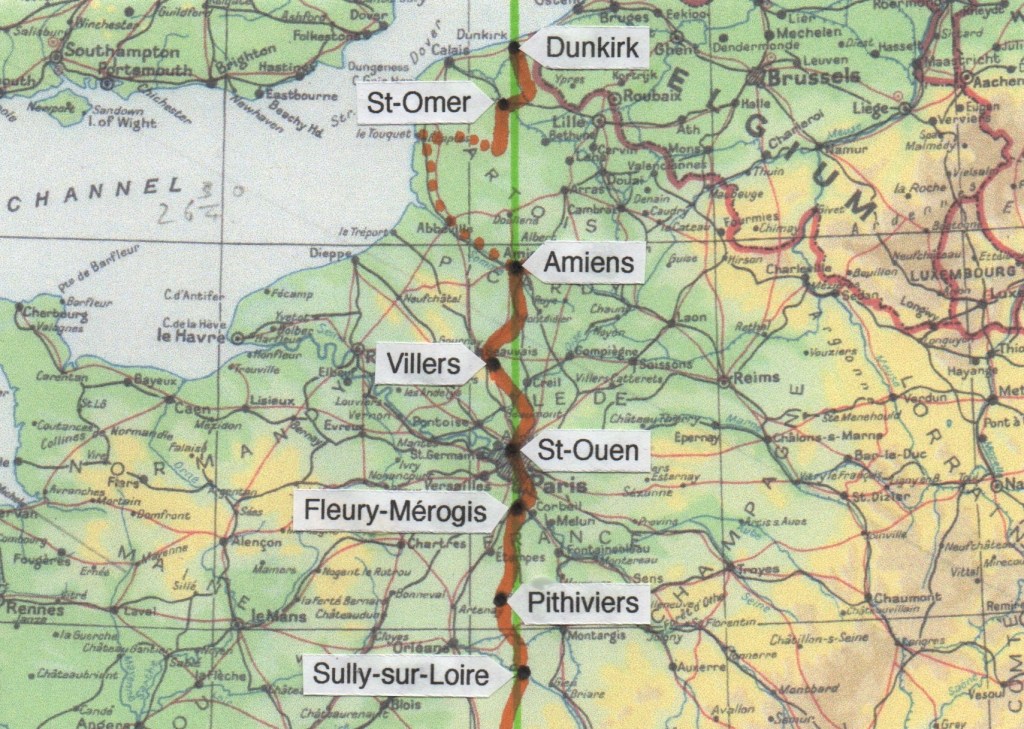

On to St Pol-sur-Mer, a suburb of Dunkirk, which is both the northerly point of the Paris Meridian, la Méridienne verte, and the location of the Première-Classe hotel I’m booked into.

The hotel is a stack of containers, on two floors, set down in an industrial park, by a motorway access point, under an enormous yellow sign visible from the motorway. I go to reception and collect my key card. I climb the prison-like metal stairs. My container has a heavy security door, and a steel-shuttered window.

Inside, the room has a finish that resists imprint. It has no presence. It is not built to age, to absorb, nothing sticks, it will never develop character. Every morning it is swept, sluiced clean, all traces removed, its memory wiped. I can imagine a Tarantino massacre one day, and the next day: business as usual.

It is a pod of plastic.

I remember literary theorist Roland Barthes’ comments on plastics (and this in 1956, as they first entered consumer culture). It is, he notes, a material named after a quality. He goes on: ‘it is the first magical substance that consents to be prosaic; its one substantive quality is resistance, the absence of yielding; it abolishes the hierarchy of substances, replaces it with one substance, so that the whole world can be plasticised.’ The magical consenting to be prosaic. The whole world plasticised. And how, in the sixty years since, that has happened!

The steps are on the outside. Indeed there is no inside to this hotel. Apart from the reception desk and the small breakfast room on the ground floor. The room is a cell, slotted into a wall of identical units, like a safety-deposit box. The car park is full, so the cells must be occupied, but no one has raised their shutter, revealed their presence. This is not a place of shared space, but of privacy and guarded anonymity, in which freedom is found in isolation.

Most of the room is filled with a bed. In the corner, there is a plastic bathroom module. But, there’s a small desk, power points, and it works. I unload my bike (I’ve brought it into the room with me), shower and change. I make tea, heating the water in my tin mug with my in-the-cup boiler. It works well. I’ve arrived at my starting point.

After a snooze, I cycle out to the long, empty beach that was, for a few days in May-June 1940, full of Allied troops, the scene of ‘the Miracle of Dunkirk’, the evacuation of 350,000 Allied troops, when the expectation had been that 10,000 would escape.

For all the proud talk of disciplined crisis management, the romance of the small boats, it is hard for me not to see Hitler’s order to hold back, halt the advance, as giving the British a final chance to come to their senses and, if not join an ‘Anglo-Saxon Alliance’ (in 1914 there had been crowds in Berlin howling ‘Rassenverrat!’, ‘race treason!’ at the news that Britain had entered the war on the French side), at least to see the sense of coming to terms with Germany. Even today the Germans seem constantly surprised that we reject their overtures to join them in running the EU, over the heads of the French.

And yet, we never quite trust the Germans. We don’t go and live there, holiday there. German competence, relentlessness, their ability to carry things through, their adherence to (their own) rules, to win, if necessary without style, leaves us cold.

Our relationship with France, on the other hand, is somehow domestic, an incompatible couple who exasperate each other, and yet spark life into each other. We each have something the other wants. We are intrigued by French self-importance, grandeur, ‘exceptionalism’, which results in what Michel Winock has characterised as an open and a closed nationalism. ‘To put it simply, their [the French] desire to shine in the eyes of foreigners, no matter how childish it may seem, does tend to promote an attitude towards the rest of the world which is generous and cosmopolitan. On the other hand, the ‘closed’ version of nationalism tends to promote selfishness, exclusiveness, narrowness, defensiveness.’ How familiar, these two versions of the French, in my experiences in France!

And Winock’s assessment is an updating of Alexis de Tocqueville’s 1856 exasperated list of French contradictions:

‘Has there ever been any nation on earth which was so full of contrasts, and so extreme in all its acts, more dominated by emotions, and less by principles, always doing better or worse than we expect?

‘A people so unalterable in its basic instincts that we can recognise in it portraits drawn two or three thousand years ago, and at the same time so changeable in its daily thoughts and tastes that it ends up offering an unexpected spectacle to itself, and often remains as surprised as a foreigner at the sight of what it has just done.

‘Insubordinate by temperament, and always readier to accept the arbitrary and even violent empire of a prince than the free and orderly government of its leading citizens; today the sworn enemy of all obedience, tomorrow attached to servitude with a passion that the nations best endowed for servitude cannot match; led on a string so long as no one resists, ungovernable as soon as the example of resistance appears.

‘A lover of chance, of strength, of success, of fame, and reputation, more than true glory; more capable of heroism than virtue, of genius than common sense, ready to conceive vast plans rather than complete great tasks.’

Ending: ‘France alone could give birth to a revolution so sudden, so radical, so impetuous in its course, and yet so full of backtracking, of contradictory facts and contrary examples.’

And yet, another contradiction, de Tocqueville’s listing of these contradictions is full of pride, to the point of bombast. Because it demonstrates exactly that French exceptionalism.

I return to the hotel. It is time to find the first Méridienne verte marker. It is here in St Pol-sur-Mer. But where, precisely? I have all the markers (hundreds of them) marked on 1:200,000 maps, and can see that it is close. But the map’s scale is too small to locate it exactly. Fortunately, geocaching has one of its Méridienne verte caches at this marker, so I can use their app. I walk across car parks, through housing estates, following the trail on my phone. It takes me to a small traffic island in a quiet suburban street. The first marker shares the island with a large, yellow buoy. Its coordinates are: 2º 20’ 11” E, 51º 01’ 44” N. The last marker is 8.5º of latitude due south.

There is a tree on the opposite side of the island. Is this the first of the millennium trees? I look south, hoping to see a thousand-kilometre line of them. Houses.

As I walk back a kestrel lands heavily in front of me in a fluster of wings, carried down by the weight of the mouse in its talons. It quickly heaves itself up and flaps away in a flurry, close to my face, its wing almost touching, leaving a space of charged energy. It brings to mind a story I have just written, in which such an encounter sets the hero on a quest. Story and life interweave. For am I not on a quest? And which is more real…?

Time to eat. I had passed a street of shops, and return there, hoping for a small, family-run restaurant. But of course, as in England, such places are long gone, and only the immigrant entrepreneurs are open in a quiet suburb on Sunday evening. There are two Libanais takeaways. One is the hang-out of youths in vests with tattooed arms and flexing muscles. The other, ‘Snack City’, is busy, the place that feeds the community. An old white couple are eating in the dining section. A group of Africans enter and shake hands shyly all round. People of all ages wait to be served.

It is run with remarkable speed and efficiency by two men, the proprietor, and his small, busy, almost manic assistant. With remarkable energy and speed the assistant bales out chips, shaves kebabs, splits pitta breads, drops in meat and any or all of the several salads, and various of sixteen sauces of worryingly vivid colour, wraps them in foil, slaps them on the counter, starts again. I order frikandelle and chips. Frikandelle is a ch’ti speciality, a deep-fried sausage.

As I wait, the little man fits a new raw kebab. It is huge and pale, almost as big as him, and looks like a giant meat-filled condom. He strips off the condom, heaves it into place – the gas jets blazing, inches from his hands – clicks, and the kebab begins slowly to turn and brown and drip in the fierce heat. All this in less than a minute.

All the food, from bags of chips and containers of salad to bottles of sauce, has been bought in, ready prepared. The takeaway trade is industrialised into factories, where most of the profit is made. The margin for the retailer depends on speed of service.

I look at the man in charge. It is his place. He is North African, mid-thirties. He has the vision of the good entrepreneur, aware of the room, checking who’s waiting, and for what, ever sociable, ever ready with a kind word and handshake, but always with an eye on the supply chain.

And too, as he prepares a complicated order immaculately, he has that ability to change scale instantly – from strategic planning, to hands-on preparation – and keep many moving situations in view and under review, always on top of things. These are the skills that could run a major company. And he works longer hours. When my food is ready, foil-wrapped and handed over, and he sees me heading for a table, to unwrap and eat with plastic fork, as I would in England, he adroitly takes my package from me, points me to a table, unwraps it, arranges it carefully on a warmed china plate, brings it to me with metal knife and fork, my coke now in a glass, with a napkin, and sets it down, asking which sauces I want. There is a grace to it, and I am touched. I imagine him training as a waiter, this is his chance to run his own business, accumulate capital, his ambition is to open a ‘proper’ restaurant. Until then, any place he runs will be run with quality.

The frikandelle tastes of nothing; it is all filler; it has no recognisable meat taste. But my stomach is filled. As I leave he makes a point of catching my eye and saying ‘bonsoir’. I have been served with grace.

I return to my room, check tomorrow’s route, and sleep well. Whatever these units are made of, they are self-contained and well insulated: the ideal of the modern, solipsistic world.

Day 2: Dunkirk to St-Omer, 44 miles.

Breakfast radio. ‘Bienvenue Chez les Ch’tis’. Paperclips and trombones. ‘The other Bruges in Flanders’. The Quest. Mercurius and the Virgin Mary. The Grand Old Duke of York. The Western Front. An engineering marvel. Two famous books. The disgraced hero.

Breakfast is a self-service buffet, and I return often, piling on the cheap pastries, front-loading calories for the day.

The radio is loud, the breakfasters’ voices are quiet. Conversations are whispered. Less from fear of being overheard than a reluctance to break into the silence. There is none of that French acknowledgement as someone enters, no ‘bon appétits’. Everyone is in their bubble, and the surrounding silence is what keeps the bubbles intact. There is no society, each is here not as a person but as a set of functions. Privacy, anonymity is all.

The radio programme has two presenters, a man and a woman. The man talks non-stop, that upbeat logorrhoea of the morning drive-time presenter. The woman laughs. She has a bright, tinkling laugh, delightful, the oral equivalent of the bright-eyed, adoring look. Her job is to laugh, her laughter carefully placed to indicate the brilliance and wit of what he says. Which, given the number and quality of her laughs must be brilliant and witty indeed. I see him preening at each laugh, puffing himself up, complacently self-satisfied. She has her job because of her laugh. She is ear-candy. Her laugh stays with me all day. I smile as I hear, beneath the tinkling prettiness, the hard edge of irony, mockery, even savagery, of one whose time, one hopes, will come.

And he does say ‘sh’ for ‘s’. Time to talk about language.

Dunkirk, ‘the most northerly francophone city in the world’, is in fact buried in the Nord département where in 1874 most people spoke no French, and still in 1972 the majority were bilingual. This was part of the Netherlands until 1659, and the native language is French Flemish, a Dutch language still spoken by 40,000 here.

But 8km away is Bergues, the setting for Bienvenue Chez les Ch’tis, the most popular French film ever, which satirises the local ch’ti or Picard language. In the film, a post office manager is exiled, for a misdemeanour, from the South to Bergues, where he finds the local language all but incomprehensible. When he asks one of the postmen if they all speak like this, the postman replies (in the English version) ‘Yesh, the Ch’ti all shpeak ch’ti – although shome shpeak Flemishka.’ ‘It doesn’t even sound like French,’ the manager complains. It is an amiable comedy, built on the humanistic premise that we’re all French in spite of our language differences, with a happy ending, a feel-good film to draw all together. Although, with not a single non-white face, it is, like many popular comedies, conservative and nostalgic, dealing with the last problem, not the current one.

And ch’ti, Picard, is French, spoken by 700,000 people, one of the languages of ‘Old French’ or langue d’oïl, of the northern half of France.

Within five miles I will have encountered three languages. And this in a country that has only one language.

Finding my way out of Dunkirk, with the usual inadequate signage, has me cycling through most of the town.

I want to buy paperclips (the tag has broken off a zip, and they are handy replacements), and I must rummage in my memory for the French name. Of course, it’s trombone, an unexpected word for this emblem of bureaucracy. The English name it for its function; the French for its form, metaphoric and subversive.

Outside a car showroom I come upon – what a curious echo! – a beautifully-restored Simca Aronde (Old French for ‘swallow’), the first French car I ever saw. It was in a car showroom window in my home town in the 1950s, imported by an adventurous distributor. I never saw one on the road. There was something noticeably different about the design, an elegance, what we would learn to call chic.

Much of the town has a run-down feel, a general down-at-heel apathy. Interrupted by the brave attempts of individuals who’ve put their lives into shops, usually selling services, often in wild colours (shades of puce and lilac are popular), and in styles that are just off, and which may or may not succeed. And with some cosmetic municipal interventions – planters, benches, flowerbeds – that try cheaply to cover over the lack of the real, the costly investment in housing, infrastructure and jobs that would be needed to give the area a chance.

At last I find the road to Bergues, by a wide canal with tall, slender poplars on either side; their leaves shimmer and scintillate in the clear air, and dapple the water on this sunny, breezy day. It is one of the oldest canals in France, constructed in the sixteenth century, connecting Bergues to the sea.

I arrive to a watery world. There are bastions sloping down into a stagnant green moat.

Bergues calls itself ‘the other Bruges in Flanders’, and it is yet another reminder that this area, as far south as St-Omer, is Flanders, a region that grew prosperous on the wool and textile trade from the thirteenth century. Entering, I could be in Bruges, with tall buildings reflected in a narrow canal.

I cycle into the centre, into the square, and enter – a film set! It’s ‘Bienvenue Chez les Ch’tis‘! The sun is shining, the square is full of colourful stalls and entertainments, the carillon that Antoine played so deliriously rings out from the familiar tower. There, see, is the yellow lunch-wagon, where the friends ate, and over there the actual post office, and behind it the sorting office (for fifteen years I was a postman) … Are they filming Bienvenue 2?

No, it’s just market day, a delicious French market day, with stalls spilling over with fine foods, and stalls selling cheap necessities. The town feels as warm and engaging as in the film. There are a few references to the film in shop windows, but in passing; this fame is just the latest ripple in the many tides of its history.

Its pride and its resilience is exemplified in its thirteenth-century belfry; entirely independent of the church, it was and is the mark of the town’s status. Each time it has been demolished it has been rebuilt: in the fourteenth, sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, and then after it was dynamited in 1944. On it is a plaque: ‘symbole des libertés communales’. Communale is one of those proud French words – in this case incorporating ‘common, commune and communal’ – for which English, and the English, have no exact equivalent. To our loss.

Outside the town hall sits one of the giants beloved of Flemish towns. This a splendid gent, a dozen feet tall, in stovepipe hat, with mauve jacket, cream trousers, an umbrella and the mildly-amused, stoical look of one who knows the world never really makes sense, but that’s life. They are still walked with pride through the streets in annual carnival. (The last of England’s perambulating giants, in Salisbury, ceased walking over a century ago.)

Panels show the destruction of the town in both wars. This area was invaded three times in seventy years, as well as countless times through history, demonstrating that it is a fluid world in more ways than one. It is still surrounded by the elaborate defensive wall, built in the thirteenth century to resist the French, and then upgraded by Vauban against the Spanish, with its characteristic star pattern ‘crown’ around the abbey.

I perambulate the wall as the market winds down, and a lunchtime torpor begins to settle.

The defences were part of the pré carré, Vauban’s line of fortifications from Dunkirk to the Ardennes, built in the 1680s to defend the new border of France. This line, if maintained, would have better served the French in both world wars in resisting the German invasions through Belgium, in this area long called ‘the cockpit of Europe’.

I resist the temptation of the ch’ti menu, with carbonnade flamande – beef and onion stew, made with beer – and ch’ti cheese (which is washed every day for a month in beer), tear off a piece of bread, cut some cheese, and eat as I walk the ramparts, then leave this delightful and friendly-feeling town as it nods off after lunch, and head south-west, back towards the Méridienne verte.

I can’t follow the line exactly, as Nicholas Crane walked England’s Central Meridian in Two Degrees West, for I’m travelling on roads. These spiral around the Meridian, and I pick my way along them, following my ‘path of desire’.

The Meridian is, for me today, the axis mundi, that links earth and heaven. It is the caduceus, the herald’s wand of Hermes, god of travellers, who both guides and leads astray.

Of him John Michell writes, ‘He is a god of both life and death, of initiation, inspiration, prophecy and delusion, the traveller’s friend. Yet to his earnest, uncritically devoted followers he is a wilful deceiver and “fool’s lantern”. His company is kept by the high-spirited of all temperaments, and the course of his study is a popular way to madness.’ I have been warned. And the roads I follow are the serpents that writhe and spiral around the caduceus. And, writes Yeats, ‘roads are the serpents of eternity … the only things that are infinite. They are all endless.’

Cycling south-west, in sunshine, into the wind, across rich wide agricultural land reclaimed from the sea, towards a Meridian marker at Bollezeele, I pass through the village of Socx. It is twinned, a flower-garlanded sign announces, with two small villages three miles from my home town. When did that happen? After I left. But another unexpected echo.

Bollezeele lies at the centre of a five-pointed star of roads.

I enter a village in thrall to that midday spell that seems cast more deeply in France. A thick almost tangible stillness. Every shop is closed, with shutters down, never, it seems, to wind up. In the bar, the squeak, squeak of a cloth inside a glass slowly turned. The wide square has been emptied of vehicles. I expect, looking up, to see birds fixed in the air. There is the sense that behind every closed window there is a beating heart pressed against the stillness, waiting. Where ‘boredom waits for death.’

Is it because of the excessive self-consciousness, the excessive self-centredness of the French, that ennui, that ‘dull glib sadness’, is such a returning theme in their literature, their ideas? To the solipsist – if nothing is happening to me, how can anything be happening anywhere? Waiting.

But, no. Beyond waiting: the consciousness behind each heart, the face above each breast has surrendered to time. So that time is simply passing through.

As I am passing through.

Of course. Here, in this empty square, with my heavily-laden bike, in the shadow of a clock that surely will never manage to push that oh so heavy minute-hand up, up, up to the zenith so that the hour may strike, I have for the first time a sense of what I am doing.

For I am on a journey.

But more than that, a quest.

I write of ‘following’ the Méridienne verte. In fact, I am searching for it, seeking it out, locating it, even creating it, with my attention to, interest in what is along the Meridian

More than that, I am journeying through France. Where I first tasted what Lawrence Durrell calls ‘the bitter-sweet herb of self-discovery’. And so much since.

And journeying through my life. For, at my age, three-score years and ten, the allotted span, twice Dante’s ‘midway along the journey of our life’, all beyond is uncharted.

But the dark edge, the line beyond which there is nothing, is visibly approaching. Since I planned this trip, four friends have been diagnosed, out of the blue, with illnesses that will soon kill them.

I feel Crane’s unease with the do-as-you-please approach to journeying of those who follow ‘desire paths’, and to a degree I share it. But, the many places I plan to visit off the line will be on my desire paths, places I desire to visit.

And yet, like a washing line on which a dog’s lead is looped, to allow it not just the radius of the lead but the length of the line, the Meridian will tether me. And the accumulation of experiences will register each time I return to the line.

A wheezing above me, as the minute hand at last heaves up to the vertical. A rattling and meshing of cogs, stasis, and then, ‘bong … bong’. A shutter cranks slowly up. ‘La Vie en Rose’ plays in the café. And I have a brief, intense sense of pattern, and aliveness.

I find the Meridian marker on the edge of the village. It is in the standard form of a metre-high concrete cylinder, with the bronze medallion on top. The bronze has gone green, the marker has stood, untouched and unnoticed, since it was put here fifteen years ago. North, there are empty fields out of sight, with not a tree. To the south is a copse of trees. It could be fifteen years old. But there is an empty field beyond. Where is the long march of trees, where are the signs of annual renewal that keep symbols, emblems, the chosen, potent?

Beside the marker is the Le Chemin de la Procession, running due south, close to the Meridian, with a sign towards La Source Notre Dame. “The pious duty of settled people is hospitality to travellers, for they are acolytes of Hermes, the errant spirit of the earth, who, as Mercurius, is also the Virgin Mary,” writes Michell. Such springs are celebrated and processed to and reinvigorated on the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin.

I cycle south along Le Chemin. It runs for a couple of hundred metres then veers suddenly west. Over the hedge, on the line, in the middle of a field of ripening wheat, is a vivid green patch, la Source Notre Dame. It is so close, the spring, to the Meridian. It could so easily have been incorporated into the celebration of the Meridian. It has, like the Meridian, been forgotten.

I head south-east, towards Cassel. It is set on a conical hill that rises oddly and uniquely 570 feet from the flat polder, not unlike Glastonbury Tor. But this, a defensible hill in the cockpit of Flanders, is inhabited to the top, and has traditionally had a military rather than a mystical role. Its commanding height has been repeatedly fought over. It is said to be the hill up and down which the Grand Old Duke of York ineffectually marched his British forces, before he was defeated by the French in 1793 and fled back to England. Although it was incorporated into France in 1678, it was still, in 1845, according to Disraeli, “quite French Flanders, where few of the inhabitants, and none of the humbler classes, talk French.”

It is tree-covered, and an even, steady ride up.

At the top is a wooden windmill, the last of twenty-nine that once ground noisily up here, and a statue of Marshal Foch, on horseback, facing east. Here he spent ‘some of the most distressing hours of my life’ staring out over the mechanised slaughter of the Western Front less than thirty kilometres away. The horse gives a clue to the reason for his hapless dismay.

The Front ran south from the North Sea, through Ypres, Armentières, Vimy, Arras, Somme (such evocative names!), then swerved south-east, away from Paris (which was saved by the troops ferried to the front-line in a thousand red Paris taxis – each charging, it is said, the full fare). On through Verdun, to the Swiss border. It was the line at which the German advance was held. It quickly congealed into a barely-moving killing zone in which half a million British, a million French, and a million Germans died. My map marks cemetery after cemetery along it, ‘Brit’, ‘All’, unmarked. There are 350 in Flanders, 280 in Somme. And many ‘ossuaires’.

It is, from the top of the hill, a remarkable, light-filled view looking east, mile after mile of flat, open land. What is now productive agricultural land was then an industrial landscape of supply depots, narrow-gauge railways, muddy roads, hospitals, camps of reserve troops, the daily exchange of casualties and fresh troops, the madness of it all laid out. It convinced Foch that the only way to prevent it happening again was to dismember Germany. He said, of the Versailles treaty, ‘this is not a peace. It is an armistice for twenty years.’ As it proved to be.

General Pétain, too, commanded from here. I will meet him in St-Omer.

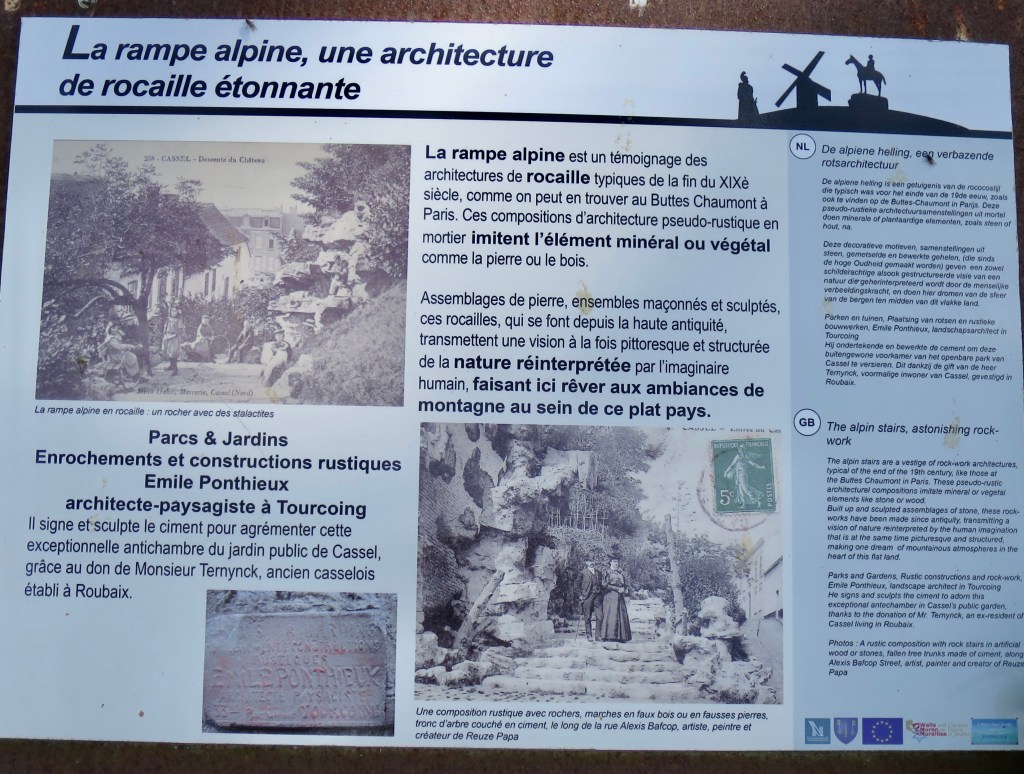

The descent into the village, on foot from this belvedere, is enchanting. It is one of those nineteenth-century curiosities, ‘pseudo-rustiques en mortier’,concrete shaped to imitate the wood of handrails and the rough stone slabs of steps, between artificial cliffs. So that instead of a simple set of even, granite steps, the way down is a romantic path through a rocky defile, between towering white cliffs, where plants nestle and cling, on ghostly white, uneven steps, with railings and seats of wood uncannily turned to white stone.

The information board reminds us that the same feature is used in the Parc Buttes-Chaumont, one of my favourite places in Paris. Aragon writes of the Parc’s Bridge of Suicides “which claimed victims from among passers-by who had no intention whatsoever of killing themselves, but found themselves suddenly tempted by the abyss,” in “the park in which nestles the city’s collective unconscious”, where we are “caught in the trap of the stars”.

Having descended the grotto-like pseudo-rustique staircase, I emerge into a Flemish Grand-Place, with cobbles and fine houses and substantial restaurants, colourful and comfortable.

Here, I imagine an awakening small-town adolescent who has read Aragon seeing himself in Paris as he climbs at night those uncanny, blanched steps. Alone, out of the noisy solidity of the given world, up to the belvedere of his dreams he climbs to stand, to lie, caught in the trap of the stars.

And I imagine myself walking at night, after a convivial meal of carbonnade and ch’ti beer in one of the Grand-Place’s restaurants, away from the chatter and colour and warmth, up this ghostly, bone stairway, to a canopy of stars, and experiencing in my mind’s eye and ear the flashes and arcs and thunder of war laid out for mile after mile below me.

Instead I am soon freewheeling down the helter-skelter of Cassel hill, and out onto the road to St-Omer, cycling into the early-evening sun.

I approach the fringes of St-Omer with the rush-hour traffic, and come upon another peculiarity of French roads – a major road, signposted with my destination, that, without warning, turns into a motorway, with no bikes allowed, and with no alternative signed. How to get into St-Omer now? I have to pick my way through villages and suburbs, using a map of too small a scale, and hard-to-read maps on my phone.

But, as I grumble my way along, I find that I have inadvertently diverted along the river Aa to the Fontinettes boat lift, an impressive piece of nineteenth-century engineering. It was a hydraulically-powered replacement for a flight of five locks that lifted boats the 43 feet from the Aa, on the Flanders plain, to the Neufosse canal, on the plateau of Artois. I climb up to the now-dry canal (the new junction is further along), and find myself in an edgy, liminal place, with too many figures apparently aimlessly hanging around, with no eye contact. I have walked into something illicit – drugs? sex? – I’ve no idea what. But it’s no place to stay. I back out, as I would withdraw from a tough bar, carefully, leaving them their private world.

My hotel is by the elaborate Second-Empire railway station.

At the door is a nail-varnish-pink torso of Venus de Milo, rather attractive.

It is a cheap hotel trying to remake itself, as all must do, against the onslaught of the low-cost chains. At the weekend it is a ‘venue’, with music to keep people drinking. Once it would have been busy during the week with commercial travellers and rail passengers. Now it relies on the occasional trade of those, like me, passing through.

It is at the bottom of town, by the canalised Aa, so I decide to follow up Robb’s intriguing descriptions of the marais, the low-lying land reclaimed for market gardens between the canals that are the only means of access, “The “floating islands” to the east of town farmed by a community which had its own laws, customs and language. They lived in the low canal houses in the suburbs of Hautpont and Lysel, which still look like a Flemish enclave in a French town.”

As I cycle through, instead of a drowned, raffish, other world, I find a neat estate of bungalows, of conventional gardens, with some fields of grazing cattle, on narrow winding lanes and canals, a thoroughly suburban and domesticated landscape.

Here and there are the beginnings of tourism – kayaking and boat trips.

And of revivalism – a basket-maker. We domesticate the different, turn it into tourism. We destroy practical working-class trades with factory goods, and then reinvent them as middle-class luxury trades. The basket-maker runs basket-making courses. It is very pleasant.

St-Omer, at the edge of the limestone Artois plateau, overlooking the plain, has a long history. Walking up into town, I pass the ruined abbey church of St-Bertin. Notre Dame in Paris was founded as a daughter house.

It is a reminder that Christianity came to Gaul not from the south, from Rome, but from the north, with the Franks.

The rivalry between the abbeys lasted for centuries. St-Bertin had a copy of the 42-line Gutenberg Bible, one of four in France, the only one outside Paris, which came to the city from the abbey after the Revolution.

A knight of St-Omer, Geoffrey, was one of the founders of the Knights of the Temple, the Templars, in 1118.

For centuries the city, on the border of France and Flanders, and close to the English possessions, was on the front line of battle and siege. Crecy and Agincourt are close. It was to a St-Omer knight, fighting on the English side, that the French king John II surrendered at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. Henry VIII conducted his only field campaign here, and must have witnessed the stylish panache of the St-Omer swordsman-executioner, as he employed him to behead Anne Boleyn, so vividly dramatised in the television version of Wolf Hall.

The Jesuit college, set up here to train English Catholics as priests to infiltrate Protestant England, contributed to the town library one of only two copies in France of Shakespeare’s first folio. It was the property of Edward Scarisbrick. He came from a family of English Catholics, several of whom died for the faith. One ancestor served Henry in France as his standard-bearer before being executed for ‘conspiracy’. Edward, the faithful Catholic, reading Shakespeare, the perhaps-Catholic? He became James II’s chaplain. Titus Oates studied here, briefly, on his eccentric journey to inventing ‘the Popish Plot’.

For all its colourful history, it is a solid, undistinguished town, connecting the plain and the plateau. A good place for a career-soldier, after an uneventful thirty-seven-year peacetime career, to retire to.

As Colonel Pétain intended in 1913.

He was 58, and had bought a house in St-Omer, selected one of his many mistresses (he was a notorious womaniser) to marry, when the Great War broke out. He proved to be an excellent wartime soldier, considerate of his men, and sensibly defensive-minded, against the prevailing French command philosophy of furious attack (De Tocqueville, on the French: “more capable of heroism than virtue”).

After the war, as ‘the lion of Verdun’, and having been appointed Marshal of France, he was flattered into politics, and began to see himself as indispensable to the good governance of France.

When the Germans invaded in 1940, sidestepping the Maginot Line by invading through Belgium, and advanced rapidly towards Paris, they cut off the British army and many of the French at Dunkirk. Pétain was appointed to head the government, and immediately agreed to the armistice with Germany.

Was there any alternative? Churchill, of course, would happily have fought to the last Frenchman. He even offered to unite France and England into one state to keep them fighting. But Pétain had spent much of his time since 1918 warning of the inadequacy of the French army, and knew its lack of capabilities. And having seen the slaughter on the Western Front, and imagining that slaughter spread across the whole of France, saw that resistance was useless.

And the armistice was widely welcomed in France.

The country was divided, the north and west under German occupation, the south and east under French control, governed by Pétain from Vichy.

But Pétain, already 84, became ever more authoritarian and collaborationist. He declared himself Chef de l’État Français, the dictator of Free France. He replaced ‘Republic’ with ‘State’, Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité with Travail, Famille, Patrie. He proposed a “social hierarchy rejecting the false idea of the natural equality of man”.

And yet there was little resistance, until the occupation of the whole of France in 1943, and the Allied landings in 1944. As de Tocqueville wrote of the French: “led on a string so long as no one resists, ungovernable as soon as the example of resistance appears.”

If he had retired in 1914, Pétain would be an unremembered colonel who lived out his retirement quietly in this dull town, dreaming of what might have been.

If he had retired in 1918, he would be the celebrated marshal who’d had ‘a good war’.

If he’d gone in 1940, he would have been the wise statesman who saved France from destruction.

In 1945 he was a traitor, sentenced to death for treason. This was commuted, against much opposition, by de Gaulle, his former lieutenant, and he died in prison, quite mad.

Note: Thanks to Dave Castell for introducing me to Bienvenue Chez les Ch’tis, and ch’ti beer.

Day 3: St-Omer to Amiens, 54 miles.

Artois. Wind and rain. ‘The Battle of the Spurs’. Mechanical trouble. On the train. The Somme valley. Entering Amiens. Jules Verne. Cathedrals and cars. The elephant and the blind men. The enchanted couple.

In the night I hear rain like pebbles on the skylight. And I wake to a grey and windy morning.

As I eat my breakfast – alone in the large, pink-paint and black-leatherette dining room, from a small round tray on a small round table, portion control – I check the weather forecast. No rain, but a steady 25mph south-south-west wind. This is bad news: it will be in my face all day, on the longest leg of my journey. And I will be climbing, onto the plateau of Artois, from sea level up to 600m.

“That chalk rise,” as Ruskin puts it, “is the front of France; the last bit of level north of it the last of Flanders; south of it stretches now a district of chalk and fine building limestone. This high but never mountainous calcareous tract, sweeping round the chalk basin of Paris, away to Caen on one side, and Nancy on the other, and south as far as Bourges, and the Limousin. This limestone tract, with its keen fresh air, everywhere arable surface, and quarriable banks above well-watered meadow, is the real country of the French. Here only have you real France.”

For Ruskin, this was the home of the Franks, whose straightforwardness was in their name.

This was the founding tribe of France. Clovis’ conversion to Christianity in 496 is the generally-acknowledged ‘beginning of France’. And in the Franks lies the root of the Gothic, for Ruskin France’s greatest gift to culture.

I will be climbing up onto the chalk plateau, out of the water-world of reclaimed polders, to a land where the problem is lack of water. Artois, Artesie in Dutch, the land of the artesian well.

I ride up through the mist, out of St-Omer, past one of those parks peculiar to France, a wide expanse of flat lawn dotted symmetrically with geometrically-trimmed trees, like chess pieces. It’s like a Resnais film, and I expect flitting figures, held poses, and a voice-over of existential angst. It begins to rain, and it doesn’t stop for three hours. In spite of jacket and cape I am soon wet and cold. There are shreds of mist, cloud, in the air.

Just outside St-Omer I pass La Coupole. It is a concrete bunker-complex, built in 1943 to prepare, store and launch V-2 rockets.

Abandoned for 50 years, it has been opened as a museum of the rocket programme, the Occupation, and the use of slave labour. It is a grim, chilling place, with the mist swirling round, and another reminder of how much France has been occupied, fought over, ruled by, trampled on, by foreigners. This area occupied three times in 70 years by Germans, fought through twice by British and Americans. There’s all the difference between a bomb blowing your door off, and a boot kicking it in. Apart from 1066, and 1688, England has been little stepped on by foreign boots.

Perhaps it’s an element in the apparent contradiction between France’s prickly nationalism, and yet its willingness to negotiate. (For years the language of diplomacy was French.) Whereas England, Britain, has always had its moated redoubt to retreat to, and has cultivated an adversarial politics.

More foreign interventions happened at Thérouanne, ten miles south of St-Omer. It is the site of the ‘Battle of the Spurs’ in 1513, where Henry VIII and Maximilian the Holy Roman Emperor, fighting on behalf of the pope, routed the French cavalry and captured the town. It was a minor battle, of little significance. But a great propaganda opportunity at a time when the visual had primacy over the verbal, when style, as pageantry, was all-important. So, Henry and Maximilian met, in full armour, in a gallery of cloth of gold. And the occasion was recorded in paintings (showing Henry of course at the centre of the battle, when in fact he was kept well away from the fighting), a Dürer woodcut, and a joint celebratory account.

While Henry was engaged in the vanity project of leading his army on the field, Queen Catherine was organising the defence of England against the invading Scots, culminating in her victory at Flodden. She sent James IV’s bloodstained shirt to Henry in France.

Having made no gains, and run out of money, Henry withdrew, and made peace with France.

The weather at the Battle of the Spurs was described as ‘the foulest ever’, and today is trying to compete. Is it really the second day of June? The land is rising, with great sweeps of open field, and occasional ridges in the lee of which villages shelter. But I am riding into a wind blowing unhindered across open fields.

And now I’m having mechanical problems, with my gears slipping. Eventually I have to lock the derailleur. Instead of ten gears, I have two, one too high, one too low. I smile grimly as, rain-battered, and jury-rigging the gears in the shelter of a hedge, next to a vast wheat prairie, I remember Hilton’s description of the old-timer’s bicycle: ‘the transmission – chainset, chain and back sprocket, the heart of the bicycle – is expertly and beautifully maintained.’

This is not good. I had set out, having ridden a few dozen miles each week for the last 4 months, after a two-year lay-off. I am not very fit. It is fifteen years since I have done a cycle tour. The bike, fully loaded, is very heavy. And now I have mechanical trouble, and no idea of how to solve it. I am beginning to wonder if I have taken on more than I can handle. But, remember the old-timer’s salutation – ‘it’s a grand life’.

At Cauchy, Pétain’s birthplace, I turn south-west, into the wind.

By the time I reach St-Pol, less than half way to Amiens, I am struggling.

I stop there, and fuel up on pizza and chips from a van in the square. Then I go to a café. As I’m drinking hot chocolate in the dark café, run by a middle-aged woman of the old school, who sniffs as she serves, I begin to shiver. My energy drains away.

As I sit, a needy-looking young woman comes in and asks if she may use the toilet. The patronne, drawing herself up, purses her rouged lips, says, no, it is out of order, the plumber is working on it right now, désolé. The young woman droops, goes out. The patronne sniffs, and smiles that tight, petit-bourgeois smile of victory. She has given nothing. When I ask to use the toilet, she smiles the saccharin smile, ‘bien sûr’, tries for complicity, then sniffs at my lack of response. I had forgotten it, that clenched lack of generosity, the French jobsworth, the petty bourgeois.

St-Pol has a railway station. This is the last place I can decide to ‘be sensible’ and take the train. I have stopped shivering, and am feeling better, but I have little energy. I head for the station.

Could I have cycled it? Perhaps. But riding into a strong wind is like cycling with a giant hand on your forehead. It’s frustrating as well as hard, and across an undulating plateau, it would be relentlessly wearying. It is the third day of a twenty-six-day ride. What if cycling on makes me ill? What if I so drain myself that I’m knocked back for the next days? My hotels and youth hostels are booked. I am on a schedule. It’s not worth it. But a problem like this, so early, is disconcerting.

The rain stops as soon as I’ve bought my ticket. But the wind still blows.

There is no longer a direct line to Amiens, and the train goes out to the coast, where I change trains. It proceeds to Amiens along the Somme valley.

The gift of this is that I enter Picardy the way Ruskin always arrived at one of his favourite places.

His Bible of Amiens is written in the convoluted, clotted style of his late writing. Yet I find its innocence and passion moving. Especially as he is writing in the 1880s, when the Somme was just the name of an attractive chalk river in France.

He writes this, about arriving from Calais at the Somme: “You stopped at the brow of the hill to put the drag on, and looked up to see where you were: – and there lay beneath you, far as the eye could reach on either side, this wonderful valley of the Somme, – with line on line of tufted aspen and tall poplar, making the blue distances more exquisite in bloom by the gleam of their leaves.”

The train from the coast pootles along the valley, picking up and setting down, students, commuters, travellers, a modern train behaving like a train of times past. The fields along the wandering river are little cultivated, mostly rough-grazing among copses of aspen, and stream-following lines of willow. There are small groups of white, very white cattle. Not segregated, as is usual, with milking cows here, bullocks of a specific age there, but mixed up, like a natural herd, unusual, old-fashioned and heartening. I begin to revive.

At Noyelles we pass a narrow-gauge steam train, with small, wooden carriages. It is packed with waving schoolchildren, and alert men with long-lens cameras. I guess it is from the Great War, when hundreds of miles of narrow-gauge line were laid to supply the Front, the carriages packed with troops and supplies going up, casualties coming back.

I leave the train at St-Sauveur. I want to cycle into Amiens. Close by is the important Celtic tribal capital of Samarobriva. It is where Caesar spent the winter after his second invasion of England. It is now the site of a reconstructed Iron Age settlement.

And it is on Robb’s Celtic Meridian, the key to his ‘lost map of Celtic Europe.’ He notes the importance to the Celts of ‘The Cult of the Severed Head’. And the Celts, or Gauls as the original French.

I cycle among the commuter traffic, through industrial terraces that lead down to the canalised river, reminding me that Amiens was in Ruskin’s day an industrial town. He first sees the flêche, the spire of the cathedral, not as a church spire, but as one black chimney among fifty “or fifty-one, I am not sure of my count to the unit.”

About a mile out, the traffic locks up, and I get off and walk. I note again the change in French driving in the years I’ve been coming here. Not only the consideration for cyclists, but the absence of horn-sounding, extravagant, theatrical gestures, expressions of fury. The drivers sit placidly as I push my bike past.

My first distant sight of the cathedral produces a sudden and unexpected emotion. I realise how much I have looked forward to this moment.I remember Ruskin’s first view of the flêche, his language stuttering to reflect his passion: “a minaret, vanishing into air you know not where, by mere fineness of it. Flameless – motionless – hurtless – the fine arrow; unplumed, unpoisoned, and unbarbed; aimless – shall we say? It, and the walls it rises from – what have they once meant? What meaning have they left in them yet? …”

To find the youth hostel, I ask at an estate agent – they’re the best places to ask for directions, as they have knowledge, maps, and their job is being nice to people. I’m soon there.

It is a big hostel, very friendly. They give me a two-person room on my own. There are many immigrant families staying, and I wonder how that works. It is well handled. As the young receptionist takes me to the bike park, she asks me how far I am travelling. I tell her that I’m following la Méridienne verte. She has never heard of it.

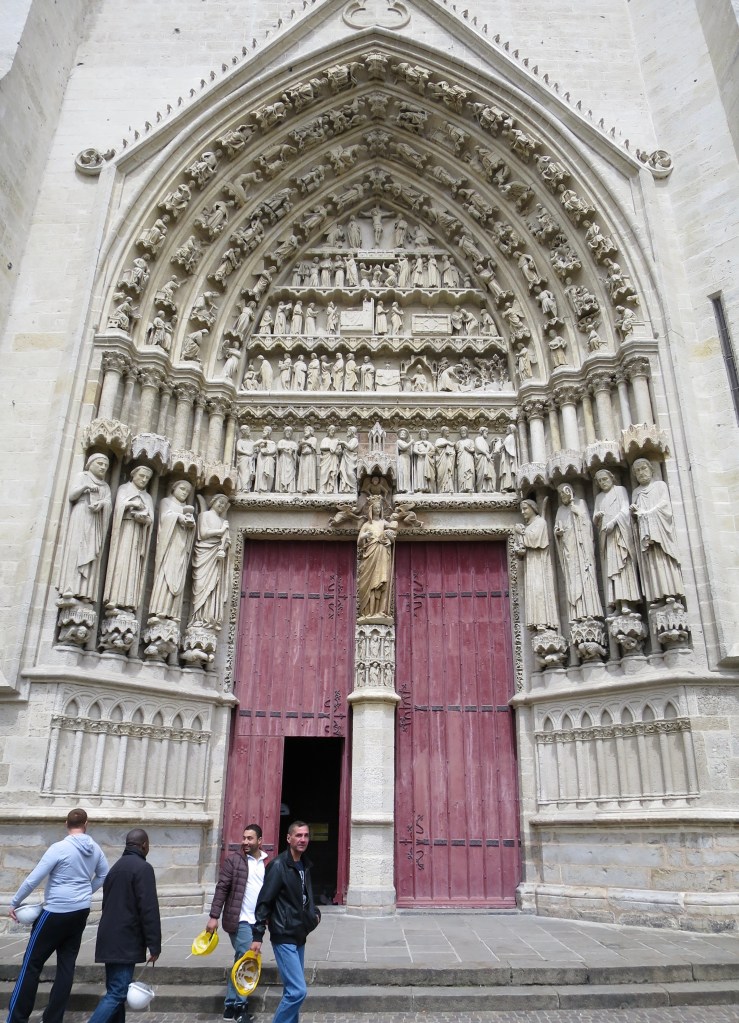

The cathedral is closed now, but I can’t stay away from it. Reading Ruskin, studying the Gothic, has made me eager to come close to this ‘Parthenon of Gothic architecture’.

I cycle in, along narrow streets lined with brick terraces, not unlike English industrial towns. Although I notice, as so often in France, that some of the houses are decorated, with distinctive courses and colours and reliefs in brick, or glazed tile courses and panels. Perhaps to distinguish the houses of overseers, or even managers? It is called, in France, variously art nouveau or art deco. But has more the feel (and is of the period) of the English arts and crafts. You find it in many French towns, and with its understated decoration of the utilitarian (and demonstrating how little is needed), it adds a spark to what is so often grim regularity. I wonder if some genius – perhaps a jobbing builder? – could invent the equivalent for our flatly-functional housing developments? As a change from the usual dull mock-Georgian embellishments.

I pass Jules Verne’s house, which is now a museum. Jules Verne lived here from 1871, and he wrote most of his vast output here. An attempt, according to his publisher “to outline all the geographical, geological, physical, and astronomical knowledge amassed by modern science, and to recount, in an entertaining and picturesque format the history of the universe.” (What my education was aimed at. Without the entertainment.) For long he was seen by the literary establishment as a writer of pot-boiling romances. Now he is included in the literary canon.

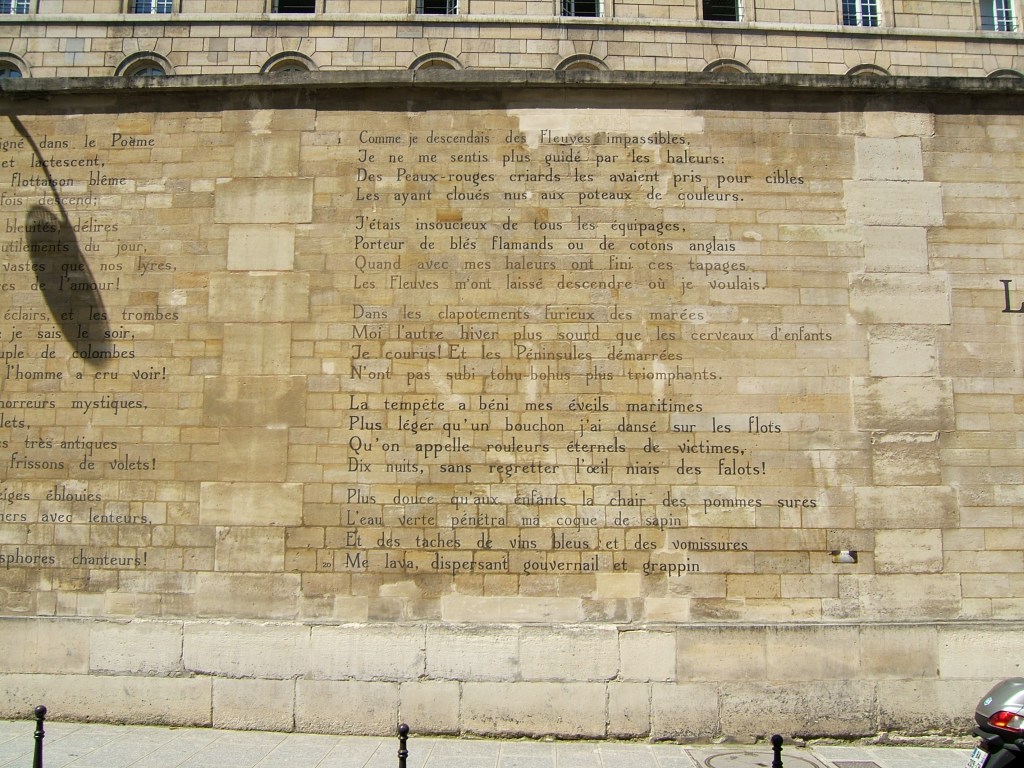

To the extent that, for example, his influence has been traced in Rimbaud’s Drunken Boat.

Reminding me that, as the sixteen-year-old was writing that most incendiary of poems, the great poet of rebellion and altered states was also a romantic adolescent, reading adventure stories, dreaming of expeditions. (Expeditions he undertook in Africa in the second half of his life, after he’d given up poetry.)

Although it took Roland Barthes to point out the essential difference between their boats: Verne’s Nautilus is an enclosed world of objective observation. Whereas Rimbaud’s Bateau ivre is “the boat which says “I” and, freed from its concavity, can make man proceed from a psychoanalysis of the cave to a genuine poetics of exploration.” From the world of objective observation, to a genuine poetics of exploration. A journey I have tried to take …

Close by is the circular Cirque Jules Verne. It is one of only two permanent circus buildings in France. It has nothing to do with the Verne; the intention is to add the aura of his name to what is one of those specialist-shaped, nineteenth-century buildings that no longer has a function.

There is a sign to the Unicorn stadium. And there are two unicorns on the town’s crest. I can’t stop myself looking for the mystical and esoteric on this most prosaic of journeys.

From a distance the cathedral looks like an enormous grey aircraft carrier docked in the middle of the city, its flêche a communications antenna. Closer, I expect to find it crowded in and trapped by small, mean buildings (as Rilke’s “ancient houses sit like fairground booths” around Chartres). A Gulliver in Lilliput. What I find are decent buildings set back at a respectful distance. (The old buildings were bombed away in the war.) And a building that in spite of being almost absurdly out of scale, fits.

It belongs. It is like a giant and friendly elephant. Barthes called the great Gothic cathedrals, “the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object” (in a passage likening them to the 1950s automobile). I find myself circling around it, this giant building, trying to get to know it.

Which of course reminds me of the blind men and the elephant, each touching a different part.

But ‘know’ is the wrong word. I am trying to experience something that is, at first overwhelming. Both in whole, and in part. There is the size, yes. But also, the complexity. And the detail.

I am especially excited by the East end, the chancel and the chapels and the flying buttresses and the tall expanses of glass, all innovations of the Gothic. Radiant chapels, flying buttress upon flying buttress, water-spout gargoyles stretching far out like dragons about to fly. And all soaringly high, an ever-changing interlaced intricacy as I move around, that is stimulating, arousing.

And not just visually. I’m aroused too by the technical bravura, sharing the thrill of those builders-for-God trying something, new thing after new thing, that had never been tried before, the triumph of the new, when it came off. And more thrilling because sometimes it didn’t come off. And each new thing having a meaning, a purpose, a place in the belief of the faith. I love this radiation of chapels and buttresses and water-spouts – for do they not represent in experience both the radiance of the word from the head of Christ, the nimbus, and, through the great, new expanses of glass (“not windows, openings pierced in the dark shell, but large spaces of empty air,” writes Barthes), the entry of light, of the worldly as well as the heavenly light, entering the sacred space, and the hearts of those within?

I find myself writing, now, as if I believe. It has that power, if not to feel what they felt, but to imagine feeling what they felt. I can, here, believe; this formidable and yet light presence, its aliveness and vividness and energetic beauty, enable me to experience as if.

I roam restlessly around the outside, along the long nave walls, past the stretched arms of the transept, around the radiant nimbus of chancel and chapels.

At last, after all the movement, I arrive at the great, static set-piece of the two-towered, three-doored West front. Static, until, as I look, it begins to move, unfold, and my eye follows the narrative of its story. It was once vividly painted, and the colours are projected on, in summer nights. But I am two weeks too early.

I leave, without looking back, letting it soak into my memory.

Back at the hostel, I realise I haven’t thought about food. I can find nowhere open near the hostel. Then I remember the enormous cheese burger, of astonishing construction, and the heap of chips, that I ate only half of last night in the square at St-Omer (drinking ch’ti beer, as I promised Dave I would. I sent him a photograph). I brought them with me, ‘just in case’.

I go to the kitchen, put them in the microwave, peer at instructions, push buttons. Nothing happens. What to do? The girl who is sitting silently in the dining room watching a TV sketch show enters silently, presses buttons, the machine hums, the plate turns, I thank her, she smiles and silently returns to her TV programme. Sitting close to her, tethered close to her by the short cable from his computer to the power point, is a thin young man with a wispy beard. They are entangled. But they don’t acknowledge each other. They are held together, waiting, in thrall.

I eat well. And I am suddenly very tired.

Day 4: Amiens to Amiens, 29 miles.

‘Roses of Picardy’. A Great War cemetery. Amiens cathedral with Ruskin. The head of John the Baptist. ‘The Venice of France’. Hortillonnages. Passerelles. Robinsonner and psychogeography. La Méridienne verte crosses the Somme. The enchanted couple, continued.

Breakfast, from a well-stocked and limitless buffet, is excellent. This is a really well-run hostel.

As I sit with my maps, working out my day, a group of English schoolboys, tumbling over each other like puppies, fill their trays with bizarre miscellanies, go through that chaos of finding their places that so quickly resolves into coteries and solitudes, consume various items from their miscellanies including swaps, clear their trays, and are gone, all this in fifteen minutes, leaving in a flurry of adolescent energy. It is the energy that, grown up a few years, was burned up, consumed on the battlefields of the Western Front, and drained from their countries.

In my thoughts, because today I am to visit those battlefields.

In the optimism of planning on small-scale maps, I had imagined myself cycling out to the Menin Gate, maybe the Canadian trenches at Ypres, and being back by lunchtime to ‘do’ Amiens cathedral and town in the afternoon. Impossibly ambitious. I decide to cycle out to the last front line of the war, and the nearest ‘Brit’ cemetery marked on the map.

As I cycle east, carried on a stiff breeze on this clear and sunny day across rolling country and through lark-filled air, I ponder Picardy. Why such romance in a word?

Is it simply from the memory of a song, ‘Roses of Picardy’? It is one of those sentimental parlour ballads, favoured by high tenors in starched dickeys, that encompass in two verses a life story. The verses unfold to a tricky tune: “She is standing by the poplars, Colinette with the sea-blue eyes. She is watching and longing and waiting, where the white roadway lies. And the song stirs in the silence, as the wind in the boughs above. She listens, and starts, and trembles – ’tis the first little song of love.” The second verse continues, “And the years fly on forever, till the shadows veil the skies. But he loves to hold her little hands, and look in her sea-blue eyes. And she sees the road by the poplars, where they met in the bygone years. For the first little song of roses, is the last little song she hears.”

The chorus could easily be, “Just a song at twilight …”, written thirty years earlier. But we surge into, “Roses are shining in Picardy, in the hush of the silver dew. Roses are flowering in Picardy, …” This is the Picardy of sentimental Victorian genre paintings, cheap emotion.

But now, as I head across country that was still described by Ormsby in 1931 as “slowly recovering from the terrible ploughing and harrowing worked by the shells in 1916-18. Its mangled villages and sub-soil will, in some places, never be brought back to use and habitation,” different voices take up the chorus. We cut from the tenor in a parlour or on a music-hall stage to men marching, the relentless 4:4 tramp of soldiers, men in greatcoats, singing in raucous, variously-accented voices, “but there’s never a rose like you!” They continue, with the bravado of men together, “And the roses will die in the summertime, and our roads may be far apart. But there’s one rose that dies not in Picardy! It’s the rose that I keep in my heart.” The bravado of men together. But what thoughts each has, alone, terrified, scratching reassuring pencil messages home, each to his Colinette, the poplars and white roads changed in his head to familiar gas lights and cobbles, and the girl or wife, who he’s never had to imagine before, never having left the street, is now transformed, has become a precious memory of every tenderness that has gone from his world.

The words were written in 1916, by a sixty-eight-year-old. It became a sheet-music best-seller, earning half a million pounds at today’s prices. Men sang it marching to the killing grounds of the Somme. As Amanda says in Private Lives, “extraordinary how potent cheap music is.”

I’m soon at Villers-Bretonneux. This was the furthest point west reached by the final German attack in 1918. It was here they were held by British, American and Australian troops, and from here, three months later, in the Battle of Amiens, they were pushed relentlessly back, along the dead-straight Roman road along the ridge, until the Armistice.

I stop at the cemetery. The sun is bright, dazzling. A strong wind blows across the open, rolling fields, making flowing patterns on the huge panels of different greens, of barley, of wheat, blowing the air clean, intensifying the clamour of the larks all around. A kestrel hangs, slips away, hangs, swoops down.

This is the official Australian war memorial. I hadn’t known. It’s a curious coincidence, that this is the one cemetery I am visiting. In Sydney last year I found the war memorial deeply affecting. Partly because it is such a fine building, that touchingly brings to the fore the lives and loss. Mainly because my father served with the Australians in World War II, got on well with them, and planned for us to emigrate there after the war. His diagnosis of TB put an end to that. And now my son is living in Australia. And, 12,000 miles away, they are expecting their first child.

I walk through the lines of white gravestones. This man was 46 years old. This man (boy?) was nineteen. Here is an engineer. There a member of the Australian Cycle Corps. I guess it’s inevitable that one begins to imagine lives, their lived pasts, their unlived futures, their families. 416,809 Australians enlisted, which is 39% of 18 to 44-year-olds. 61,514 died, 155,133 were wounded. A fifty percent casualty rate. 20% of Australia’s adult male population were casualties in the Great War, 12,000 miles from home.

Looking up, I see the parallel lines of the 2,000 graves stretching away. I imagine this cemetery a thousand times bigger, to represent the Allied dead. I double that, to include the German dead. White gravestones as far as the eye can see over the rolling countryside.

It is a place, this open, wind-filled hilltop, for expanding speculations. And for the handwritten commonplaces (what else could one write?) of the memorial register: ‘Never Forgotten.’ ‘Rest in Peace. Thank you.’ ‘Our grandfather is here.’

I cycle back through Villers-Bretonneux (twinned with Robinvale in Victoria, Australia), on the Roman road (almost certainly the appropriation of a Celtic highway) along the chalk ridge that stretches east behind me, arrow straight, forty miles to St Quentin, where the front was from 1915 to 1918. I pick up food, return the hostel, lunch, snooze, and head into Amiens.

Ever since I read The Bible of Amiens, Ruskin has been my guide, especially to the cathedral.

What to make of John Ruskin? Remembered more these days for his sexual problems and his late madness, but in his day the leading art critic, social commentator, and passionate advocate for the working man’s right to beauty and a civilised life, his books on the meagre shelves of the humblest homes.

Charged with realism, for his belief in exact description; with intellectualism, for his high ideas; with aestheticism, for his passion for beauty. But his was a belief in looking, seeing, experiencing, thinking about. For “the configuration of an object is not merely the image of its nature, it is the expression of its destiny, and the outline of its history.” It is worthwhile bringing this to the consideration of any object.

And this summing up, by Marcel Proust: “Ruskin is one of those men who, like Carlyle, are warned by their genius of the vanity of pleasure and, at the same time, of the presence near them of an eternal reality, intuitively perceived by inspiration. Talent is given to them as a power to relate this reality to the all-powerful and eternal to which, with enthusiasm and as if obeying a command to conscience, they dedicate their ephemeral life in order to give it some value.” And, “as a sort of scribe writing, at nature’s dictation, a more or less important part of its secret, the artist’s first duty is to add nothing of his own to this divine message.” After pausing to consider this, I am ready to enter Amiens cathedral, with Ruskin as my guide.

Enter, says Ruskin, not by the West door, for the effect of all great cathedrals is similar from this dramatic entrance. Enter Amiens, rather, from the Street of Three Pebbles, through the South porch, beneath “the pretty French Madonna, with her head a little aside, and her nimbus switched a little aside, too, like a becoming bonnet.” (A copy, now. Her original is inside. And she wears a crown rather than a nimbus.) “And put a sou into every beggar’s box who asks it there – it is none of your business whether they should be there or not, nor whether they deserve to have the sou – be sure only that you yourself deserve to have it to give; and give it prettily, and not as if it burnt your fingers.” I do this, and enter.

Enter at the cross-centre, the apse, “for it is not possible for imagination and mathematics together, to do anything nobler or stronger than that procession of window, with material of glass and stone – nor anything which shall look loftier, with so temperate and prudent measure of actual loftiness.”

Attend especially to the fifteenth-century wood carvings of the choir, “Flemish stolidity mixed with the playing French fire of it … under the carver’s hand it seems to cut like clay, to fold like silk, to grow like living branches, to leap like living flame. Canopy crowning canopy, pinnacle piercing pinnacle – it shoots and wreathes itself into an enchanted glade, inextricable, imperishable, fuller of leafage than any forest, and fuller of story than any book.” Full of images and symbols, working at different scales. Except that, as Ruskin says, “in old Christian architecture, every part is literal: the cathedral is for its builders the House of God.” I’ll come back to this when Proust rejoins the conversation.

Beginning – never clearer than here – with the plan of the cathedral, that represents the form of Christ. The nave is the body, with feet at the West end. The transepts are arms. At the crossing is the heart. The chancel, the most sacred space, with the divine presence in the enclosed choir, is the head. And around that head, separated from it but related to it, radiate the chapels to the saints, the most easterly the Lady chapel dedicated to the Virgin, forming the nimbus or halo.

I follow Ruskin around the outside of the chancel curtain, along the ambulatory, past the radiant chapels, each with its slender walls and vast expanses of coloured glass, made possible by the pointed arches, the ribbed vaults, the flying buttress upon flying buttress that I had so admired outside.

And then, to the nave. I walk the length of it, without looking up, to the West door, before I turn. It is high. 132 French feet high specifies Ruskin, 42.3m the modern measure. Which is 144 cubits, the height of the walls of the New Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation. It looks higher, is made higher-seeming, to an eye used to English cathedrals, by its narrowness, a mere third of the height. It is breathtaking. And, after the vitality and exuberance and illumination of choir and chapels, curiously austere, a simplicity of line that carries the eye up, emphasising one’s smallness. Then leads the eye forward, along the nave that is now the stem of a flower, to the apse that is a bloom of light.

This is the largest French Gothic building by volume, and exceeded in height only by ill-fated Beauvais.

It was built between 1220 and 1266, under Louis IX, to house the head of John the Baptist. This had been looted from Constantinople in 1204 in the Fourth Crusade. (Constantinople of course was a Christian city.) I think of the Celtic ‘Cult of the Severed Head’.

For Ruskin, Amiens was “not only the best, but the very first thing done perfectly in its manner by northern Christendom.” For Viollet-le-Duc simply “The Parthenon of Gothic architecture.”

But what is it for me? I realise that I have been experiencing it through Ruskin’s text. And Ruskin was a devout, if idiosyncratic Christian. Out through the West door, I walk away, then turn to see the great West front. Three-doored and twin-towered, with detail upon detail piled up, like a giant organ; or, rather, the music of a great organ. Architecture as frozen music. This is Ruskin’s Bible of Amiens, and he devotes many pages to describing and explaining the meaning and the message, of each detail, at every scale, calling it “the simplest, completest and most authoritative lesson in Christianity.”

There are three figures of Christ. But none is of Christ crucified. For “The voice of the entire building is that which came from heaven at the moment of the Transfiguration: This is my beloved son, listen to him.”

Ruskin was one who could still believe in this message of Christianity. Which Proust, writing a few years later, resists. He describes the cathedral as “a book written in a solemn language in which each character is a work of art that nobody can understand anymore.” For him, and I guess for me, “There is no Logos; there are only hieroglyphs.”

Hieroglyphs. I re-enter. Stephen Murray writes this: “The power of the cathedral to liquefy the most hardened visitor is palpable on the astonished faces of those who enter the light-filled nave with its soaring spaces and repetitive forms,” its aim: to soften the surface of the soul – what an expression! – a means to an end. “That end nothing less than the stamping or imprinting upon the softened surface of the soul a series of powerfully interacting images that pertain to the idea of redemption through the Church. And the central image is that of Christ himself, stamped upon the soul at the point of entrance through the Beau Dieu.” Outside, it soars with the rich story-telling and evocation of the West front, and the virtuosic variety of the structural elements of the East end. Inside, its power comes from the grandeur of height, the simplicity of scale – or rather of size, the simple reaching up.

I marvel at the quality of the woodwork in the chancel, at the same time as, peering at it through a metal grill, I’m irritated at my exclusion from it.

I admire the tombs of the bishops, bronze, “cast at one flow – and with insuperable, in some respects inimitable, skill in the caster’s art,” still, centuries later, liquid looking.

I find ‘the weeping angel’. Amiens was occupied by the Germans for a month in 1914, but thereafter it was in Allied hands, an important logistical hub. Many soldiers passed through, many sought solace in here. The ‘weeping angel’ is an emblem of that time, a sentimental seventeenth-century carving on a tomb behind the high altar that featured on thousands of postcards sent home. It returns me, with its sentimentality, to ‘Roses of Picardy’, reminds me that at times of emotional woundedness it is the sentimental, even the kitsch, that speaks directly to us; all we can bear, with its softness, when there is no skin over the wound.

Where the head of John the Baptist should be, in the North aisle there is an icon, and this note: “the reliquary cannot be exposed in the winter months [it’s June! Where is it?] because of humidity. You are invited to collect your thoughts and venerate this icon, gift of our brother Russian Orthodox Christians.” The first cause of the cathedral is now hidden away.

And by a chapel is this notice: ‘Confessions, Saturday 15:00 to 17:00 hours’. The whole population of Amiens, confessed in two hours? What a change, this downplaying of two elements so fundamental to the power of the medieval church: the relic, to be visited, and venerated, to touch and to be cured by – and of course to donate to, an important source of revenue; and confession, the church’s spy in people’s hearts, one of its primary instruments of control.

The cathedral has been, since the Revolution, owned by the state; the church is its tenant.

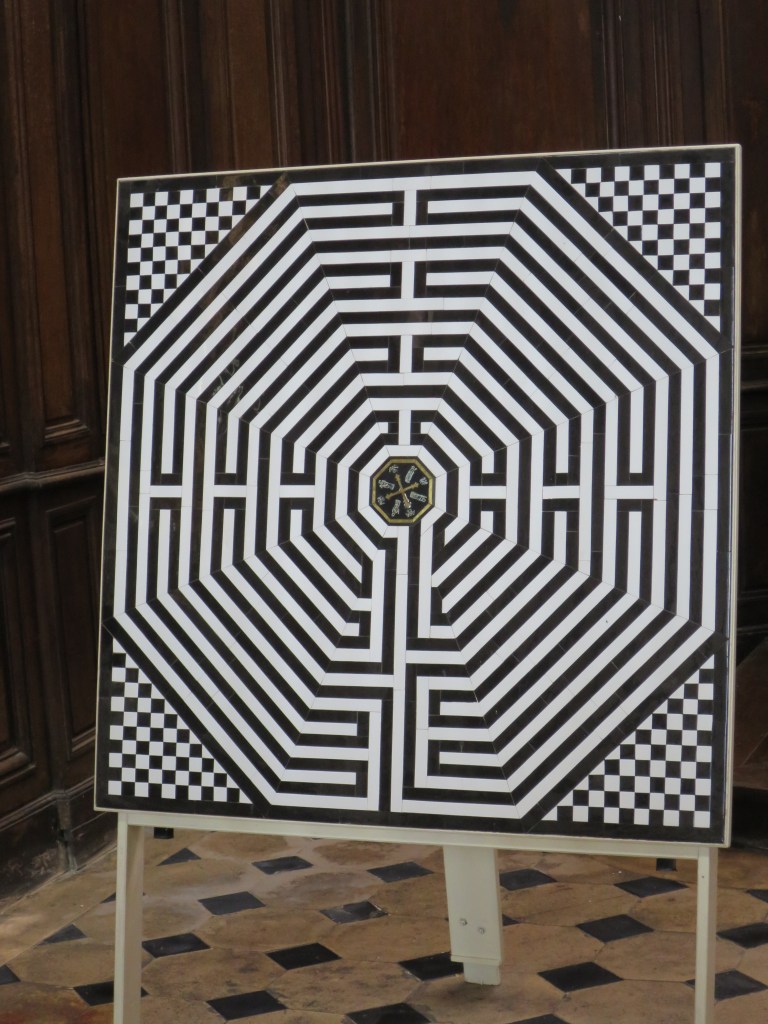

I arrive at the Cretan labyrinth, laid out on the nave floor.

I note that little boys rush round it, or cheat by stepping off the path, or become suddenly self-conscious and break off. While little girls proceed through it with knitted determination, walking quickly but accurately, their set expressions opening like brilliant flowers when they reach the centre.

The labyrinth. At the centre of my novel set in Greece is the labyrinth as the path to self-discovery.

And after the legendary and mysterious unicorn of last night, perhaps it is today’s metaphor for my journey along the Meridian, my forever-meandering journey along a non-existent line. And today’s question about my journey across France is this: is it a unicursal labyrinth, which, however complex has but one path, that leads inevitably to the goal; or is it a multicursal maze, designed to confuse and puzzle, but having many paths through to the goal, and which makes possible choice, serendipity, surprise? Which brings me back to Hermes, who both guides and leads astray.