Day 19: Belcastel to Albi, 51miles.

The first smile of the South. Dante and tripe. ‘Benveguda en Tarn’. Pink city. Crusade against Christians. A congregation facing hell. The great explorer lost. Diagonals of the Hexagon. The garden restaurant. Burger à point.

It is another cold night and I hardly sleep. I’m up, packed and ready to leave long before anyone is about. I decide that Belcastel can live without my camping fee, whatever it would have been, and push my bike up out of the village.

It is an expansive June morning, the sun up long before people, the blue sky vast, the untenanted, uninfringed air rich with oxygen as I breathe deeply in and of the silence. Detail. The last wisps of mist are dissolving from the tops, going, gone. Now just green and blue. The quiet munching of a horse by a gate, the shiver along its back and the shake of its head as its big eyes follow me before it returns to its munching. There are simple roses in the hedge, small, delicate, pink. Again, I’m full of memories from living here. Of cutting a branch of ash for a hay-rake handle, stripping the bark off the damp, bone-white wood, splitting and fitting the handle in the chestnut head, the work unfolding perfectly, all this to a chorus of bantam cocks one early midsummer morning before the neighbours’ alarm clock had shaken them awake. Standing on the top, and seeing my shape cast on the snow-like mist below me, surrounded by a rainbow nimbus, a glory – what was it, what did it mean? Years later I discovered it’s called a Bröcken spectre.

But now, as my thoughts have been meandering, my footsteps, pushing the bike, have wandered. I’ve no idea where I am. I am in a maze. Every tiny lane looks equally important, there are no signs, the lane that begins upward, around the next corner curves back down. I return to the crossroads several times, once even back down to the village itself. Should I have left a camp-site fee? Is this Hermes’ early-morning trick, a little pipe-opener for a day of mischief? What to do? Keep trying.

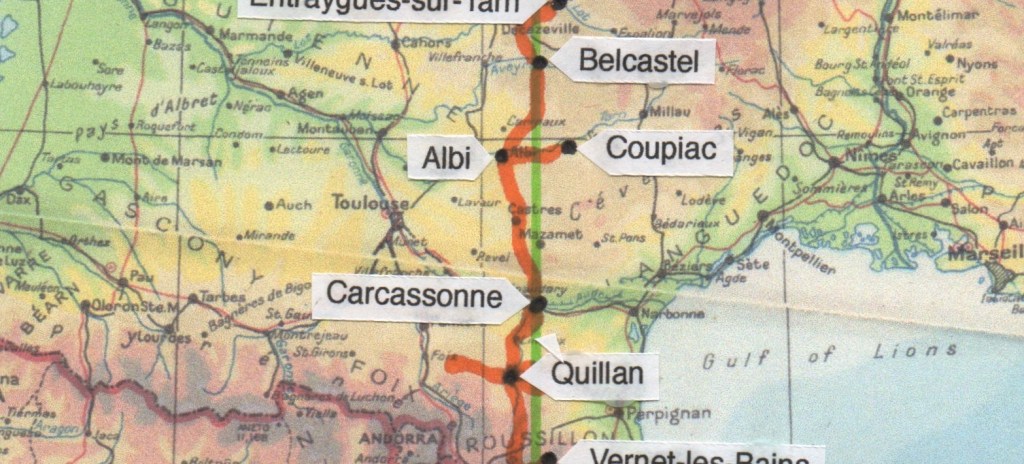

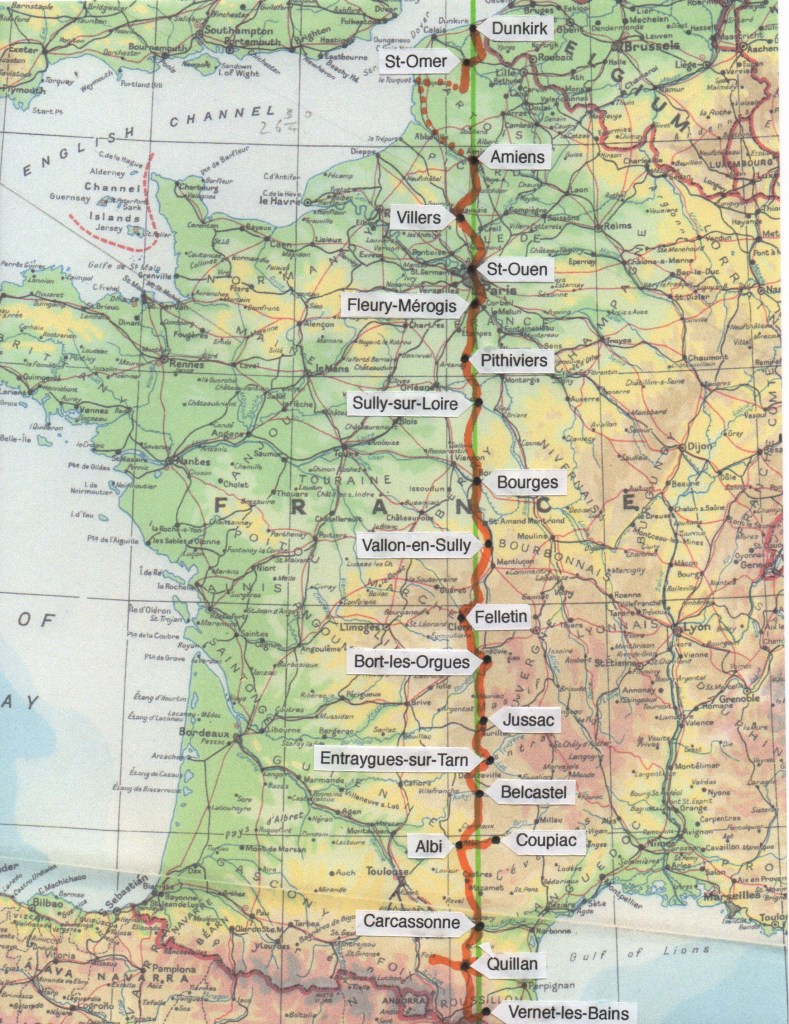

After two hours, I emerge unexpectedly from the maze, onto the D997, at Colombiès. I am back on the map. I head south, to the junction with the D911. I am at 750m, today’s high point. The land falls away, spreads before me. This is my ‘first smile of the South’.

I pass a roughly-painted sign by the road, “NON AUX EOLIENNES. IMPOSTURE ECOLOGIQUE.” ‘No to wind turbines. Ecological imposture.’ How French, on a protest sign, ‘Imposture’!

And a small, new factory unit, ‘Tripous. Fabrication. Vente directe’. In English ‘tripe’ means rubbish; in French, trickery. Hermes must be the patron-saint of French tripe-dressers. The best tripe I ever tasted was in a sandwich, peppery and hot, on a thundery summer day in Florence, between heavy showers, outside the church where Beatrice is buried (so many notes left to her, in a bowl in the church; as I considered leaving a note, wanting an answer that tumultuous week), close to Dante’s house. We had a tripe shop when I was young, the last tripe shop in town, bleached seams slithering around on the marble slab in the sun-filled window, and billowing like formless albino marine creatures in the vats of water in the yard. The young woman at this establishment has returned to the family farm to ‘devote myself to tripe’. As well as selling it fresh, they can it. Tinned tripe? Do the trotters they sell here come from the pig factory, the abattoir I worked in? not far away, now.

Heading south and down, a wind at my shoulder, pushing me on, the whole of the South is spread before me, light-filled air, ochre and green fields softening in the distance to a misty blue. There is one last sharp reminder of the west-draining streams I have been crossing for days, as I descend to and climb up from the Viaur.

Then I cross into Tarn. Which markets itself as ‘Coeur d’Occitanie’, and welcomes me ‘Benveguda!’

The buildings change, it seems at the département boundary, from grey stone with steep roofs of scalloped grey slate, to ochre render and shallow red-tile roofs. And the road margins, I’m sure, lose definition, from road to verge, from verge to field. There is something altogether looser about the South. For as well as crossing a département boundary, I have crossed a pre-1790 Province boundary, out of Guyenne-Gascogne. I am now in Languedoc.

I pass through the village where a friend and her new husband came to live, make a new life together. He liked it, she didn’t. She went back, he stayed. They divorced.

Through Carmaux, but no time to visit its museum of mining. And there, at last, is Albi.

For miles, on the long straight run into Albi, the cathedral is visible. Side on, high up, it is a huge presence, dominating the town, a red brick oblong with what looks like a fat chimney at one end, industrial-looking. An appropriate look for a church that imposed its rule with such factory efficiency. And for a building built to be a constant reminder to the people below of the ever-ready ideological machinery within, and its power to torture and burn to death at will.

I stop at the bridge over the Tarn. It is a lovely view: the wide river, crossed by the two rhythmic-arched bridges and the diagonal weir, fringed by dark trees, the town heaped up in attractive cubist geometries, the cathedral sailing high. I had forgotten how pink Albi is! The raw red of the ubiquitous brick mellows with age, and the pale mortar further softens the effect. It has a dusty, rosy, salmony pinkness, set off by the green tinge to the river, the white water off the weir, the Midi blue of the sky.

Before I enter the town proper, I pause to ponder which Albi I am entering.

There is our market town forty years ago, where we would drive once a month in our ancient, canvas-seated 2CV to stock up in the whole-food coop and Mammouth hypermarket, have long, hot showers, and visit like-minded friends in the old quarter.

There is the town I recorded and reinvented in a novel.

There is the fourth major town on the Meridian, the fourth medieval cathedral, another chakra on the spine of my journey, and my entry point to the South.

And there is the town that gave its name to a heresy and a crusade, that colours so much of my relationship with the South.

All are interfolded, with abrupt shifts between. I cycle across the bridge, and up to the cathedral.

The Albigensian Crusade, the first crusade against heretics rather than infidels, was proclaimed in 1208 by Pope Innocent III. (I note the names popes give themselves, that allow them to distance themselves from their actions.)

It happened because of a coming together of interests. The result was a war of atrocities and destruction that ravaged the South for thirty years, followed by eighty years of the Inquisition, in whic

tens of thousands were slaughtered and thousands burned to death. A Christianity closer to the original Fathers, and a culture of subtle traditional relationships and high artistic achievement (celebrated by Dante) were destroyed.

The French crown, the French state, colonised the South.

Its name was less because Albi was the centre, than because the Cistercian fanatic, later Saint, Bernard had received a notably hostile reception when he preached here in 1145.

Albi fell in 1209 without a fight, after the massacre at Béziers.

But in 1234 the Albigeois, outraged at the torturings and burnings by the Inquisition, forced the bishop to hide in his own cathedral.

His successor, Bernard de Castanet, was made of sterner stuff. He had both religious and secular power, and this was useful because, although the church pronounced on heresy, the state carried out the sentence. Bernard was judge, jury, and executioner. He was the Inquisitor for Languedoc, and a close ally of the Dominican Inquisitors.

His first act was to build in Albi a fortress-like bishop’s palace, la Berbie. This was his base, and also a detention facility for the Inquisition.

By 1287 he felt powerful enough to pick a fight with the town, increase church dues ten-fold, and begin to build, using these dues, a new cathedral, modelled on his brick palace-fortress.

What to make of it, this church-fortress? It is huge, towering, impregnable. But impregnable against what? It comprises twenty-nine round buttress-towers, connected by curtain-walls that rise sheer and blank to lancet windows fifty feet up. The walls are topped with battlements. It is unlike any other cathedral. It is the largest brick building in France, possibly Europe. (Who has counted the bricks?) Although each canny Albigeois could count the bricks his taxes had paid for. While he remembered the Hebrews in Egypt, making bricks for their masters.

At the same time as the followers of Suger were building Notre Dame in Paris, with pointed arches and flying buttresses and expanses of glass, flooding the apse with light and expressing spiritual aspiration, even yearning, this fortress was being built as a manifestation of the church’s oppressive power over the community.

I am reminded of another church that was built at the charge of a community and as an ever-present reminder of their defeat at the hands of authority, the Sacré-Coeur in Montmartre. That sugar-loaf confection was built in the years after the Commune. It was, perhaps still is, a tradition for the locals to spit and utter a curse as they pass.

Inside, it gets weirder.

It is a vast space. There are no aisles and it is the widest transept in France. In contrast to the blankness of the outside, the walls and ceiling inside are covered in trompe-l’oeil patterns, as if to confuse the eye and draw it to the mural on the west wall.

For in here the congregation, by some vindictive reversal, faces west, with their backs to the high altar. Like naughty children facing the wall. Except this wall they are forced to face has upon it a vast and ghastly picture of the Last Judgement. And at its centre is a great doorway, that could be the mouth of Hell itself.

Behind them, in the area from which they are excluded, which they never see, in the richly-decorated choir, the Holy of Holies, in the company of a host of beautifully-crafted Bible figures, in the presence of the Virgin and child, and in the orient light from the apse, the canons sing the holy offices. I can’t wait to get out.

The cathedral took 200 years to build, and in that time Albi grew wealthy, growing and trading in saffron and pastel, woad. Woad was the only blue dye of the Middle Ages, before indigo arrived from the East. Weld provided yellow, and madder provided red, and the wools of the great tapestries were dyed with these three.

Referring to the Toulouse-Albi-Carcassonne triangle, a contemporary wrote, “Woad hath made that country the happiest and richest in Europe.” So the cost was easily borne.

But imagine that money available to the old South, to Languedoc, to the patrons of the troubadours …

In 1794 the cathedral became a Temple of Reason.

In 2010 it was designated a World Heritage site. It is a great draw for tourists. Its image is on a million postcards and souvenirs. Like the people of Montmartre, the Albigeois have learned how to turn a profit from the instrument of their oppression.

I need a break! I walk past the white outline of a man on the pavement – art intervention? crime scene? – to a place I never visited when I lived here. (Too busy. Too serious. Foolish!)

The Toulouse-Lautrec museum. In 1970s the town was decidedly ambivalent about its most famous, or notorious son, an aristocrat, but also a stunted drunk who lived in brothels, and painted prostitutes and vaudeville acts. Now he is celebrated everywhere in the town, with quotations plastered across dress-shop windows. And the museum is now in Bernard de Castanet’s Berbie. That I like!

It is an excellent museum, and I can’t stay long enough; I will have to get back to Albi: but for a while I escape to Paris, to Montmartre, to the few streets where he lived and painted. I had sped past his studio on my hectic ride across Paris, tipping my hat as I passed.

I am struck by how modern he is; less in his style than in his understanding of the market-driven metropolitan world. In his paintings of prostitutes I see his awareness of the market. Not the market for his paintings, but the market in which the girls were renting out their bodies. He depicts with shocking matter-of-factness how they are, all the time, even when they are off-duty, marketing themselves. Wearing clothes, adopting poses, taking on characters, acting in ways that will interest (‘arouse’ is too strong a word) the imagination of the client. Waiting in positions that they hope will draw his jaded attention. Each is trying to create a personal market, and thereby a buyer. There is something irremediably bleak about these pictures of girls selling access to and misuse of their bodies, in a buyers’ market.

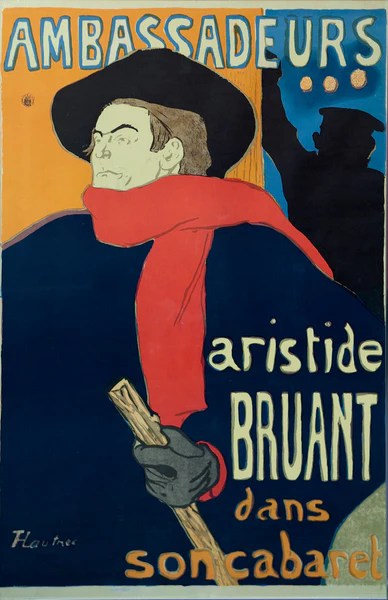

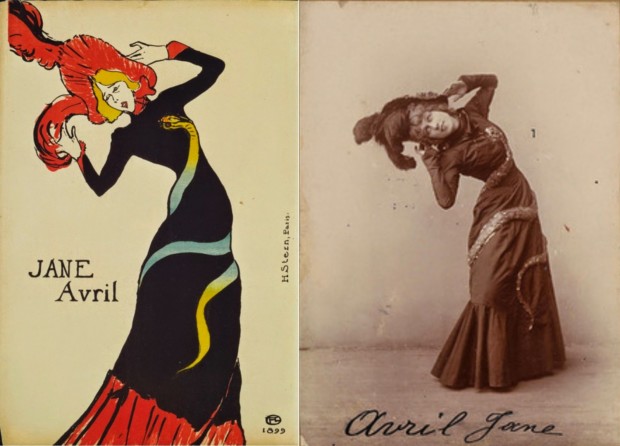

And his awareness of the market is clear in the lithographic posters he created for artists and venues. New laws allowed bars and cabarets to open. Which meant that competition was intense, and every act, every venue, if it was to succeed, had to develop an image. The new lithographic process and cheap printing allowed these images to be fly-posted everywhere. Henri was a genius at developing images.

Looking at his posters for Aristide Bruant, Jane Avril, and comparing them with photographs of the artists, and the many sketches he made along the way, one sees how carefully, and brilliantly, he both captured and created, in an iconic pose, the essence of their act.

For the venues, like the Moulin Rouge, his depictions stop the action just at the moment you want it to go on – so you have to visit the venue to experience it going on. He is a great artist.

And what adds a dimension to his greatness is that, while he is depicting the artists at their most attractive, and ‘authentic’, he is showing both the frailty of the individual, and the artifice of the situation. He is depicting not the substance, but the market. And while he was selling the acts, he was selling his artist-self – he had his own initial colophon. (Like that other great artist-salesman, Dürer.) He is the Warhol of his day. Dead at 36, younger than Van Gogh. And, to add an irony, he is remembered today much less for his paintings than for the posters that were for him the hack work that paid the bills that enabled him to paint. I return to Albi, refreshed.

To the Albi of a novel.

It had taken me a long time to dare to imagine, invent, make up, to be able to ‘tell stories’ (which as a child was a phrase used for ‘lying’), to act upon Picasso’s ‘art is the lie that leads to truth.’ It was a while before Barthes’ deconstructions in Mythologies showed me that the self-evident is simply the unquestioning acceptance of the prevailing ideology. Before I learned from Levi-Strauss in La Pensée Sauvage that different cultures don’t just express reality differently, they experience it differently. Before Harari in Sapiens showed me that myth-making, the ability to imagine, and “to transmit information about things that do not exist at all” is the defining feature of Homo sapiens.

Now to revisit the places and objects at the beginning of the novel (Diggers and Dreamers, p.9-11. See in the drop-down menu MY BOOKS.), unvisited in forty years.

The public bathhouse is still here, and a shower is still cheap, only 80c.

The war memorial is close by, and the white gravel.

The crane is long gone. It had been there for the rebuilding of the old quarter. The old quarter was rundown, overcrowded, unsanitary, poor, lacking facilities, and occupying a site with development potential. It was lively, cheap, a community with washing-lines across the lanes, plenty of eyes on kids playing in the streets, useful local shops and services. It was demolished, and rebuilt on the same street plan, not in rough stone and render, but in ‘trademark’ Albi Roman brick, with shops along the lanes, and flats above. But the flats were too expensive for the locals, so they were moved out. And the shops and cafés were upmarket, for visitors and incomers, not for a local community: boulangerie replaced by patisserie, épicerie by chocolatier, mercerie by a fashion chain, no places for tradesmen’s workshops and yards. Visitors, safe in familiarity, flock in. It has become a place that time passes through, as styles and fashions change, but that doesn’t age: take a photo, and you could fix it, years later, to a specific year’s fashion campaign.

But where is the giant anchor? Surely I didn’t dream it, invent it, the anchor, “set on a plinth, eighty miles from the sea. I sniff it to see if I can smell the sea. It smells of iron and heat.” …?

It must, I realise (how little I knew, then, about this area!) have been a memorial to le comte de Lapérouse, naval officer and explorer, native of this town, whose amazing scientific expedition to the Pacific in the wake of Cook explored and mapped the coasts of Alaska, California, Hawaii, Australia, Japan, Korea and Russia. He sent back his invaluable records with the English from Australia, then disappeared. His last message said he expected to be back in France by June 1789. Just in time for the Revolution. (Apparently a benevolent and just captain, what role might the returning hero have played in making the Revolution work …?) After many searches, remnants of his ship were finally found in the Solomon Islands in 2005. But I don’t find the anchor.

I have remapped the Albi of memory and invention onto its present actuality. It is a town busy with commerce, busy with tourism. And, at this point in the late afternoon, busy with children. Because the streets have been roped off and waiting zones established for an evening of children’s cycle races. Disorientated, I stare at my tourist-office map, trying to work out where my night’s lodgings are.

As I peer hopefully around, I become aware of a young man sitting, staring at me. I say, hi, and he clicks into life, as if he’s been waiting for me. He scoffs at my tourist office map and pulls out his own map of the town. He asks where I’m heading, indicating my bike. I say proudly, to Perpignan. From Dunkirk. ‘Ah’, he says, unimpressed, ‘une Deeagonaale’. What? Others have done this? He recites the six Diagonals, bike rides across the Hexagon, between Brest, Dunkirk, Strasbourg, Menton, Perpignan, and Hendaye. They are organised, I learn later, by Amicale des Diagonalistes de France. Each has a time budget. Dunkirk to Perpignan is 100 hours.

He tells me how to get to my destination, and sits back down, inert once more. As if he is an automaton waiting to be switched on. Or an actor awaiting his cue.

He is another of those characters, like the woman at Saint-Denis station, the young man in Epignay, the man in the square in Pithiviers, who seem to have been placed, either to guide me, or to lead me astray. Spirits of Hermes, of the hermetic path. Was this character’s role to deflate me? To show that what for me is something special, is in fact something ordinary? And by extension to make me ordinary? Or was it to stimulate me to say, defiantly, this is my particular journey, my own diagonale, that I fully acknowledge and own …?

I find my lodgings. An odd word to use, but it is neither hotel nor hostel, an informal conversion of a two-floor flat, with individual bedrooms and a big shared kitchen.

It is good to be back among people, even if it is with that awkwardness of difference of language and type, and the simple desire in each of us for privacy. An old French couple, who seem to have taken up residence, the wife having that way of turning every place into a version of her home. A woman on her own who seems to want to talk, but at the same time has a way of deterring conversation. But it is good to be inside, a solid building not a flapping tent. And my room is comfortable, and it has a decent bathroom, I can shower, do laundry and sort out my things.

I bring my bike into the lobby, and put it in the cellar. The building is the classic nineteenth-century block of apartments, the provincial version of the block in Perec’s Life A User’s Manual, which opens, “Yes, it could begin this way, right here, just like that, in a rather slow and ponderous way, in this neutral place that belongs to all and to none, where people pass by almost without seeing each other, where the life of the building regularly and distantly resounds.” The heavy outer door that slams shut no matter how carefully you try to close it; the bare, dark, neglected lobby undecorated for half a century; the stone staircase of uneven, worn steps spiralling past door after door; the sounds and cooking smells of different lives seeping out from behind each; big locks and big iron keys; the curved wooden handrail loose on the iron holders; ancient light switches. The general neglect that enables cheap living now, on the capital (including labour, of course) expended when it was built.

Having showered and changed, I go out. The heavy door slams. I stand on the street, by the big elaborate coach doors that lead into the block’s courtyard, watched by the glittering eye of the amateur concierge behind the lace curtain.

Which way to go, in search of a meal? It is a long residential street, tree-lined, the evening sun dazzles along its length, the evening is pink and warm. There are a few shops but most of them are closed down. Do I want to go back into the centre? Too fashionable, too far. I want a quick meal. There is a burger place across the street.

Not a plate-glass window Formica place, with grudging sitting space, but a small restaurant that has adapted to the modern eating habit that demands burgers.

The small, energetic woman ushers me through the dark empty restaurant, with its candles in wine bottles and gingham tablecloths, into a garden, shaded by the buildings around, with a couple of trees, mild and comfortable. Oh, this is surprisingly nice.

I order cheval burger and beer. How do I want it cooked? she asks. I say ‘moyen’. ‘On dit, à point’, she says, less correcting than informing, nicely done. Of course! I’m mentally kicking myself for having forgotten. Then I remember Barthes’ essay on steak-frites, how bloodiness is the steak’s essence, and “even a moderate degree of cooking cannot be explicitly expressed; such an unnatural state requires a euphemism: a medium-cooked steak is said to be à point, more as a limit than a degree of perfection.”

I sit back, sipping my beer. There is a family, with a noisy child demanding attention, a listless mother, and a man who spends the whole meal on his phone, chewing as he listens, swallowing before he speaks. An old couple shuffle in, regulars on their night out. They order quickly, automatically, and then settle down to the puzzles that are printed on the place mats. Instead of tablecloths, cheap restaurants have individual paper place mats, advertising the town, or shops, or products, with, in this case, puzzles, and horoscopes. My horoscope reads, “Do not throw yourself lightly into a hazardous project. Be more prudent, your finances will be less impoverished.” This is the usual advice for the impulsive Aries. But having ignored the first piece of advice in making this journey, I decide now to follow the second: I will not have a pudding.

As I wait, I ponder something that had occurred to me while writing Diggers and Dreamers, years after our time here. What if we, having got off the train here, with our trunks, instead of taking the bus up into the hills, as we did, to stay with English friends who had persuaded us to come and do the ‘self-sufficiency thing’, preliminary to buying our own place, what if we had stopped in Albi? What if she, who wanted to be French in France, had got a job here, teaching, or in an office. While I, who wanted to be a stranger in France, stimulated by both the difference and the freshness of a new country, had written …?

As I look around the little garden, observing, noting – the accent, panse for pense, merci bieng, the people around, local colour, the vividness of the unfamiliar – what if, instead of a year working in an abattoir (120 pigs a day, killed and processed), and a year working on a house and the land, gardening, pruning vines, scything hay, making wine, bottling vegetables, making baskets, mending tools, fixing a cuisinière with an iron plate from the blacksmith and fire clay dug from a place in the woods he told us about, struggling with an old car, roofing a house, what if I had just written?

Except that it was exactly those two years of hard manual labour, of being practical, of débrouillage (getting by) and bricolage (improvising) that had been a crash course in separating me sufficiently from my privileged bookish upbringing to enable me to reconnect to a self I had been losing touch with since I was eleven. And that in the years after, back in England, had informed my writing.

Dinner arrives. The difference between burger places in France is less the burgers than the chips. These are chunky, not greasy, excellent. I had been trying to believe that cheval burger is made of horse meat (having conceded that canard burger isn’t made of duck), but this, the second I’ve had, like the first has a fried egg on top. How did it get the name? Horse and rider? I eat well, and saunter back. The glittering eye through the lace curtain does not blink as I heave open the heavy street door.

I close the shutters, those ingeniously-designed but fiendishly complicated wood and iron French shutters, definitively old France, and am in bed before ten.

Here in Albi I have a sense of arrival. But also the sense that this is the beginning, that one focus of my journey is just ahead. Tomorrow I will head east, across the Meridian, into the hills, and revisit our house of forty years ago.

Day 20: Albi to Coupiac, 56 miles.

Return to the hills. Our village revealed. The carved stone buried. Encounter in the café. The wild boy reconsidered. Our house. The one-armed man. The Virgin’s veil. The threshing-machine. Camping by the lake. Pot au feu with the young couple.

I wake early. Today I will be at La Balme, our old house. And I still haven’t worked out what to do.

What was once a hamlet of half a dozen peasant families, by 1975 comprised a farm of a hundred hectares, and our property of two hectares. We had bought it from a family who had left after their barn was struck by lightning and burned down, burning to death the animals inside, selling most of their land to the Bonafets, the neighbours. At first, they had come out from Albi a couple of times a year to prune and pick the grapes and make wine. But at some time they gave up even that, and when we went into the cobwebbed cave we found only rancid vinegar and spoiled barrels. They had waited, through the flight from the French cities of the disillusioned young after May 1968, the continuing interest of city-dwellers in second homes, until the arrival of the ecologically-inspired idealists from Northern Europe after the oil crisis of 1973, and a naive English couple, to try to sell their house. Of course we paid over the odds, bargaining being to them a skill bred in peasant blood, to us a form of rudeness.

We got on well with our neighbours, especially with Gaston, madame’s bachelor brother, who lived with the family as unpaid hand, and who enjoyed teaching us the old ways that his brother-in-law the farmer, and Didier, the farmer’s son, weren’t interested in. I had imagined when we moved in that our arrival would be a breath of fresh air, especially for madame, who hardly ever left the farm, but also for Didier and Yvonne, the children. But over time I have felt ever more guilty, that we had disturbed their self-contained world by moving into the long-empty house next to them, and then introduced the disturbance of the ‘outside world’ by selling it on to second-homers from Montpellier.

A friend had said – go in, introduce yourself, they will be glad to see you. My ex-wife had said – you’re not daring to go there, and actually speak to them, are you? I had to go there.

But who would be there? Forty years on, the older generation would be long dead. Didier, the son, had been around twenty. He spent his time driving around the farm too fast in the tractor, and driving along the lanes too fast in his car. He returned from his first holiday, on the Med, eyes big with disbelief, saying ‘we live on gold, and eat shit.’ Would he have sold up, to a progressive neighbour. Or a farmer from England attracted by cheap land and EU subsidies? Would he have married, continued the family tradition, the farm now run by his son?

Perhaps I will ask at the mairie if the Bonafets are still at La Balme? Perhaps I will cycle up to the farm and say that I lived here forty years ago, do you remember? Perhaps I will pretend to be lost on my way to Coupiac, and check the place out? Perhaps I will simply not go there, leaving a hole, occupied, as it has been for forty years, with memories and regrets, invention and guilt …

I breakfast well, in the spaciousness of the big kitchen, with fresh bread and fresh coffee laid on. I’ll be back here tomorrow night. Tonight will be my last night camping, somewhere near the Tarn.

I cycle across the Place Jean Jaurès. Every town in France seems to have one. Who was he? Born in Castres in 1859, he was a teacher in Albi. One of those young men, like Alain-Fournier’s father, who, following Ferry’s reforms, were tasked with introducing the values of the Revolution – democracy, secularism, laïcité, Enlightenment thinking, national identity, into education. He was elected deputy for Carmaux, and in 1895 helped the striking glass-workers of Albi to found their own bottle-making cooperative. It is still in business. A socialist, he was assassinated in 1914 for being against what he called the capitalist war.

I am soon on the familiar D999. Past where the vast Mammouth hypermarket had stood. It’s now a small ‘Carrefour Contact’, ‘le concept de commerce de proximité’. Our hypermarket has become a corner-shop. Is this a sign of what’s to come? Will this be like visiting childhood places? Will everything have shrunk? I cross the railway line embedded in the road. Already disused in 1976, it has still not been tarmacked over, as if they are still hoping for a train to cross.

There are many large lorries on the road, and I worry that with the opening of the Millau viaduct this has become a new main road. But they are serving the new industrial estates on the edge of Albi. The road soon quietens as I climb steadily up from the plain.

The road rises, and the rain starts. At least the wind is behind me. But it is hard to keep dry. An old woman, walking slowly, hunched under a sack, says as I pass, ‘vous allez mouillé’, with the grim satisfaction of one used to hardship; nothing bad can happen if you expect the worst. But, oh dear, to arrive at our old place in the rain, with a night of wet camping to follow …

I cross the Meridian. There is a sign saying the Tour de France will pass here on 17 July, and the road will be closed from 12:30 to 15:45. I saw the Tour for the first time in Yorkshire last year. I had seen many fast bike races, but the way the leader, away on his own, punched through the air, like a fist, took my breath away; it was an experience of raw power that still makes me shiver.

Past a sign for the restaurant in Coupiac, advertising ‘workers’ menu’. The workers at the abattoir, where I worked, ate there, a single meat ‘dish of the day’, potatoes, vegetables served as separate courses.

A sign, ‘Millau – Open’.

Past the memorial to four Resistance fighters, killed on 31 July 1944, a month after D-Day, a fortnight before the landings in the south of France. Three were members of the Free French Army, an attempt to unify the 200,000 Resistance fighters. It is a dark, gloomy menhir, by dark fir trees, and it has always made me shiver. I asked Gaston if he was involved in the Resistance. Yes. Did he fight? He gave his self-deprecating smile, who, me? I carried messages he said, and cooked. But he would still have been deported, shot or strung up if caught. A woman in a village close by was still known as the woman who collaborated by sleeping with the German Commandant. The husband took back this village Helen, and they were still together in 1976.

Wheat, barley, hay, pasture, vines, maize. A patchwork of small hedged fields. Areas of deciduous and coniferous woodland. A small-scale, various, undulating landscape. A raggedness, as if too much neatness would be irritating, with margins (here’s a wheat field stopping at a house lawn, with no fence between), an area not too much under pressure, where you can live and let live. And, as I approach the highest point, 750m, the cloud clears, and the sun comes out, illuminating the variegated fields and the dark green woods that to the left drop down into the Tarn valley, ahead rise to the Massif, revealing the sunlit blue distance. Struck, awed by its beauty, I have to stop. And look.

It looks like the promised land. I lived here. Why hadn’t I seen its beauty? Why had I clouded it with her, my, our unhappiness, an unhappiness that she, I, we had brought with us from our pasts? We had a house and land, bought and paid for, in cash, with the money I’d saved from a year of working ridiculous hours (often 100 a week) as a hospital porter. We had ideas, energy, abilities, skills. We might at La Balme have established a new way of working, with the locals who were still connected to the old ways, with the incomers and the new ways we brought, a new cooperation …

But perhaps the problem was in the word ‘self-sufficiency’, a buzzword of the time.

She, I, we were still raw from the wound left when we tore ourselves away from the life we had been trained for, that we’d embraced, as new entrants into the middling classes who run the system. We were monks who had been too obedient, but who had then lost their faith, and left the monastery. Outside, we needed time to heal, to find another way of being, beyond the off-the-shelf simplicities I’d learned from books at the Ecology Bookshop. We’d lost one faith, but immediately converted, simplistically, to a new one. We had been in too much of a hurry. Unnerved, I guess, by the uncertainties of the times, the ‘success’ of our contemporaries, the fear of being left behind. In too much of a hurry. So we couldn’t, didn’t dare to give this place, this way of life, time to soak into us, change us. Instead of giving ourselves that time here, she, I, we hurried back, there. Left all this, and what might have been, left it here, the unlived life.

1000 miles clicks past on my milometer.

The road falls, into the valley of the Rance, down 400m in one snaking, swooping, exhilarating run. The sun is hot, and my wet shirt soon dries. I’m breathless when I get down.

Approaching Saint-Sernin, our village, it is as I remember. The village rises sheer from the river, like a miniature Potala Palace. I ride across the bridge that marks the entrance to the village.

But, wait, something is wrong. The bridge is in the wrong place. Have I so misremembered? What has happened?

I return to the beginning of the bridge. There is a turning down, along a road lost among trees, down to a stone bridge, the old road bridge. When I get down to the old bridge, I look up. The new high-level bridge is a mini-Millau viaduct. It cuts out the steep drop and rise up, the sharp bends. I push my bike over the old bridge, and try to scramble up, on the line of the old road, wanting to enter the village the old way. But it is fenced off. I have to return and enter the village across the new bridge, on the level. Everything has significance. I take a deep breath as I cycle slowly up to the square. I have these few moments to remember with my old eye, see with my new, to register what has changed.

The feed-merchant is now a modern garage. There is a statue of the enfant sauvage. The village hall is still there, under the car park, where we went to a dance that was one of the most dispiriting evenings of my life. The creaking old hotel has been refurbished to something more boutique (I’ve checked the prices). The Grand Café, on the square, has become the centre of village life, with live bands and events advertised, decent music playing now, a place that is trying, and hopefully succeeding. The alimentation générale has closed down. The basket-maker is long gone. I park my bike, and saunter down the narrow village street that runs away from the main road.

We rarely came here, beyond the alimentation. I came here more with Gabrielle. I know nothing of Saint-Sernin, the internet has almost nothing.

The village is on a bend in the river, where a tributary joins. It is a fortified medieval village. But I have no idea who built it or why. Gabrielle was curious, would have asked, found out, connected it to history, to France.

One day a touring theatre group, Les Baladins du Havre, performed for one night in the square. She would have spoken to them, invited them back, at least found out where they were staying and joined them for the evening. Arranged for other groups, for singers to come.

The houses had interconnected lofts, to facilitate defence, a placard says. There were gates and towers. Was this for the petty conflicts of local lords? Was it involved in the Albigensian crusade, the Hundred Years War, the Wars of Religion, the camisard revolt? The little bridge is called le pont des morts; it was where bodies were carried on the mourners’ backs, across the river to the cemetery. Was there significance, symbolism in that? There is a stylish Renaissance house – whose? Why?

By the tributary stream, Le Merdanson, there is a copy of a small, carved stone menhir, set up where the original (now in the museum in Rodez) was found. Dated to 3500-2500 BC, it is a stylised female figure, remarked on for its ‘sculpture soignée’, carved with a complex iconography that would repay long study.

It is reputed to have been thrown down and buried in 658, when St Martin was preaching against such pagan images.

Perhaps, rather, it had been hidden here, among the gardens that lined the stream, the peasants’ secret continuation of the old ways, the Celtic ways, venerated, buried to fructify and ensure the productivity of the gardens?

In a ten-minute walk I have learned more about, and stimulated more of my interest in Saint-Sernin than in two years living here. All these stories, that I might have explored, expanded upon, written about …! Past the mairie. I won’t ask about the Bonafets (she might phone them!). I decide that I will turn up and pretend to be lost. Who will be there?

I go to the Grand Café for coffee. I want to sit outside, collect my thoughts, make notes, prepare to leave the village and take the road to La Balme.

A woman is sitting on her own, in the sun. She beckons me over, insists on buying me a drink. Beer? No, coffee, thank you. She is drinking beer. As we talk, in French, I realise that she is rather drunk. She has that serious drinker’s way of trying to camouflage her drunkenness, of both acknowledging and doing nothing about her drinking. ‘I like beer,’ she says slowly. Then, after a long pause, ‘sometimes I drink too much,’ she says. Each sentence is carefully enunciated, separate, as if searched for and then hauled up out of a bag of sentences. And sometimes the sentence is not quite the right one. It is an odd conversation, especially as she doesn’t speak very clearly and I’m reluctant to ask to her repeat in case she thinks it’s a comment her state. Where had I come from? I tell her. ‘I was in Albi this morning,’ she pronounces. How did she get here, I ask? She sits, silent, looking at me, as if trying to put something together, gives up, says, ‘it’s complicated’. Is she staying at the hotel, I ask? Sort of, she says. She gets up abruptly to speak effusively to a young woman with a child. The child shrinks from her. Returning, she asks my age. I tell her. She says I look younger than that. And that she is younger. How to ask questions that don’t sound like leading questions, especially of a woman who is raw with her vulnerability? She is divorced, she says, gets on well with her ex-husband, she has a daughter in Marseille. Is she on her own? Should I offer to stay, to sleep with her? What am I thinking? Such bizarre thoughts! I’m feeling quite unhinged, trying to think of ways I might comfort her, make her feel better. Why do I want to help her, save her? What from? What for? She greets and waves extravagantly to some boys going into the bar, they are embarrassed, joke among themselves. ‘They like me here,’ she announces loftily. What to do? I need to get on. How to leave her without ‘leaving’ her. I look at my watch, well, I’ve enjoyed – she stands abruptly, cutting me off, gives me the briefest handshakes and is gone, as if to an urgent, just-remembered engagement, she’s left me, better to leave than be left, the English have no manners anyway. A strange encounter, signifying … what? Hermes again.

Unsettled, not having had the time I wanted to ponder, I walk over to my bike, wheel it past the hideous statue of Victor of Aveyron, the enfant sauvage, and set off, pushing, up the so-familiar hill, the Route de Guergues; the road of the mountain pass/narrow valley.

Victor was one of the most famous cases of ‘feral children’, children who lived in the wild, supposedly in the company of animals, and who never, crucially, learned to speak. He was captured here on 6 January, 1800, and became ‘The Wild Boy of Aveyron’. He was sent to Paris to be examined, and was looked after there by a Paris physician who wrote a book about him. He died without learning to speak. François Truffaut made ‘L’Enfant Sauvage’ in 1970. In the eighteenth century, under the influence of Rousseau and later the Romantics, the enfant sauvage easily becomes child to the ‘noble savage’, man in a state of nature, ‘gentle, innocent, a lover of solitude, ignorant of evil and incapable of causing intentional harm.’ (Benzaquen.) Whereas Enlightenment thinking was that being truly human meant to be rational, to be socialised, and, above all, to develop language.

I ponder this as I push my bike slowly up the long hill. I see now that we – my ex-wife and I, others of our generation – hadn’t realise how confused we were. We had been educated out of our class, working-class kids who’d ‘passed’, gone to grammar school and university, Hoggart’s “uprooted and anxious”, and didn’t know where our loyalties, interests, even desires lay. I had been over-told. I did not know if the system was well-meaning, opening new horizons for me, and enabling me to bring benefits to those I would serve; or exploitative, taking my intelligence and aptitude and twisting it to the purposes of the established culture, for whom I would be the equivalent of a native colonial administrator, imposing alien values on ‘the people’ from my new position of privilege. By 1970 I just wanted to be left alone.

We wanted to be left alone. To ‘find’ ourselves, to explore alternatives, to live without societal pressure, to be ourselves. Whatever that was. Implicit was the presumption that by moving back down a couple of rungs on the ladder of social evolution, through urbanism and commercial farming, back to peasant farming, we would be two rungs closer to the essence of ourselves.

We saw Truffaut’s film, and to us Victor was our original self, an innocent, in a state of nature. Who was progressively insulated from the ground and air with shoes and clothes, blinded to the subtle light and shade of the natural world by artificial light, living in a world increasingly filtered by words, his natural individuality suppressed by social conformity. As we felt had happened to us. We saw ourselves as reluctant children of the Enlightenment, who were rebelling against that blinding light, becoming more feral. It’s not a coincidence that long hair and bare feet were big things at that time. But we’d hardly registered that our village was where he had been captured. Strange.

In fact most feral children have been shown to have been abandoned by adults because of their physical or mental deficiency. Recent research on Victor points to his having few survival skills, living not in the wild, but close to houses, surviving on scraps, more street-child than wild-child; that the scars on his body, far from being the result of battles with wild animals, were the result of physical abuse, and that his behaviour was consistent with autism or trauma. Each generation – ours obsessed with lost innocence, this one with child abuse – rewrites its stories to suit its mythology.

At the top of the long hill is the small stone wayside crucifix, now almost buried in the hedge, going the way of the Neolithic menhir in being lost and forgotten. The head of the cross is wonderfully simple: a disc, with four discs cut out of the stone to create the shape of the cross. There is a primitive Christ upon it. It is a Fanjeaux cross.

Fanjeaux was a Cathar stronghold, and I have seen this pattern of cross described as a Cathar cross. But the Cathars did not recognise the cross – what true believer, they said, would venerate the instrument of their Lord’s torture? And Fanjeaux was where Dominic Guzman, who founded the Dominican order, based himself in his campaign against the Cathars. The Dominicans ran the Inquisition. Cathar? Catholic? It is no clearer. Is it very old? It could be any age.

As I freewheel slowly down to la Balme, I am alert to note changes.

How clearly I remember it as it was, this lane! On which, one night after rain, walking with a torch, I found several fat lizards, black with yellow patches, crossing slowly. Fire salamanders! Anything seemed possible in that world.

There is a large, new industrially-built sheep house, of steel, corrugated roof sheets and slatted wood.

The vines are gone. Ours were next to the neighbours’, and each produced a year’s wine. We shared the vendange with them, and the feast that followed.

The vegetable gardens are gone, the hedges around them ploughed out and the gardens lost in a field of wheat. Again, they had been next to each other, and by a source that never ran dry. Gaston would leave his tools with their heads in the water, so the wood swelled and the heads fit tightly. Patiently he guided us in our planting.

There are no animals out, as there were then, the cattle grazing quietly, the sheep being chivvied with whistles and trills to remind them to eat.

The potato patch is gone; Gaston would plough it and then earth-up the growing potatoes using the oxen.

Now it is a farm of open, empty fields, of haylage, wheat and pasture.

As I approach the hamlet, no dogs run out barking, the excitable, ill-trained dogs that would run along biting at the tyres. Gone too is the graveyard of road vehicles and farm implements, a history of the mechanising century laid out as in a farm museum, with nettles poking through.

I stop in the farmyard, park my bike. The duck pond has gone, and the waddling ducks, and the scratching, crooning hens, and the midden-topping cock-adoodling bantam roosters. Gone too is the byre where were tethered the huge, slow oxen, and the cow from which Madame returned each morning to her kitchen with a jug of warm, foaming milk.

It is now a modern farm, with housed sheep, machine-milked I’m sure, some pasture, the rest for haylage and wheat, no other animals, no other life.

‘Our’ house is little changed. It has been tidied up, with new windows, and a flagstone terrace laid in front. As I would have done if I had stayed. After reroofing the house with tiles, I had carefully stacked the stone-flag lausses I had stripped off, ready. Good to see them used. The house is shuttered, shut up. It must be a holiday home.

There is a tractor at the bottom of the yard, bucking backward and forward as the driver uses the digger at the front to root out a tree. It stops its bucking, and the driver climbs slowly out.

He is a round-faced, comfortably-built, slow-moving, amiable-looking man. This should be Didier. But forty years ago he was slim, moustached, impatient, and always rushing. Perhaps the Bonafets did sell up, and this is a new, progressive man?

And then as he climbs down, I see something that shocks me to the core. The man’s left forearm is missing. Cut off six inches below the elbow, ending in a tuck of skin. Who is he?

He speaks, in that casual, inquiring way that paysans do, even on their own property, so little of the brusque, proprietorial English farmer. The words tumble through a mouthful of marbles. I’m taken back forty years, instantly. The figure is not, but the voice is, Didier. What happened? A car crash? An accident on the farm? When?

He has grown up (grown up? He must be sixty) to be, not like his father, thin and bent and foxy, but like his uncle Gaston, easy-going and amiable. I stick to my story, tell him I got lost going to Coupiac. He lifts his cap (Didier never wore a cap), scratches his head, trying to figure out how I could end up here, explains in great detail a route along minor lanes I have never travelled adding, I’d drive you there, if you didn’t have the bike.

As we chat, he asks where I’m from. I say England. His face lights up. A young English couple used to have the house, there, he says, pointing to ours. I’m expecting him to say, five, ten years ago, thinking that it must have passed through many hands in forty years. He says our names, first and second names, remembered, without hesitation, after forty years, brought instantly to mind.

And isn’t this my moment to announce, ‘mais Didier –c’est moi, je suis Keith!’?

I don’t. And is it really because I fear he is about to continue, … ‘ – and those bastards ruined our lives!’?

I say nothing.

How his face had lit up when he recalled! Now he carries on matter-of-factly, the light gone. They, les jeunes anglais, sold it to some people from Montpellier. He bought the house back from them and ran it successfully as a gîte for several years, but … the rushing account is lost among the marbles. But the sense is that it wasn’t worth the bother. Perhaps after his accident. Perhaps when his income grew so he didn’t need it. Perhaps when he acknowledged that he would only need the farm to support a bachelor.

All my years of guilt. When, for all his shy distance and youthful swagger, he had actually enjoyed having us, the hopeless but enthusiastic young foreigners with the strange friends, next door, around the place. As Gaston had enjoyed teaching us the old ways, because no one else was interested. The moment has passed.

I say, absurdly, that I like the farm, ask if I can take photographs. Of course. Am I cycling alone? he asks. When I say ‘yes’ he pulls a ‘rather you than me’ face, but slightly wondering, too. Where am I heading? How do I come to be in this area?

And, as we talk, I see that behind the curiosity, he has more than a suspicion who I am. I can see him at the Saint-Sernin monthly market, lunching with the other bachelors – as his uncle used to do – casually introducing and framing his story: strangest thing, this chap came on a bike, said he was lost, I’m sure it was the young Englishman who bought the Gascets’ place next door. He was about the right age, an old man now, no idea why he didn’t say. He must have had his reasons, it makes you strange, living in a city. The piece of news to share, his moment to hold the conversational stage, the take-off point for that market-day’s conversation.

Now I must get a pioche to get this tree out, he says. Pioche, the peasant omnitool. And how I want to get my pioche from our cave and help him with the task! I go to look around.

This was where our barn was, already burnt-out and collapsed when we bought the place, but with enough good stone to build a house. A gîte, maybe. Or a new house for us. Overlooking the valley, facing the rising sun.

Below it, our meadow, that I scythed for hay, guided by Gaston’s amused instruction. In the middle was the willow I cut for the wands to weave a basket, rustic but serviceable, also taught by Gaston, two hours’ work to make a basket that would last for years. It would have made a lovely garden, surrounded as it is by feathery ash trees. From one of which I cut the handle for my hay rake. And there is a wonderful view. Down across the abandoned terraces, now lost in woodland. Chestnuts, where one could gather limitless nuts, the old staple, ground for flour, before potatoes and wheat were introduced. We boiled a few, for marrons glacés, for friends in England. Down and then up, on the other side of the valley, to a patchwork of fields, where there is a perfectly-placed church, and the road along which the headlights of silent cars passed at night. And the rolling blue Aveyron uplands beyond.

But the stone has been bulldozed into the foundations, covered in earth, the barn quite gone. As they had thrown the lausses off their roof when they reroofed their house, dumped them somewhere; while I brought mine carefully down, for the future terrace. Which they had used when they made the terrace in front of ‘our’ house. The willow is gone.

I turn back to the farm.

At the end of their farmhouse is a small, modern extension, where Didier lives his bachelor life. The main house is closed up. I wonder at what point he became a bachelor. Was the farm not big enough for a family? Was it after his accident? Another story I will never know.

Gone are the cages of rabbits and pigeons. They used to bait a cage and then, when a pigeon went in, drop the door shut with a string from the first floor, a peasant smile at their cunning.

The fine stone sheep house, where monsieur hand-milked the sheep twice a day, cursing in the stifling heat, the milk going to Roquefort, has had its lausse roof stripped, been reroofed with corrugated sheets.

The pig, that lived for a year in his little sty, fed on waste food and milk, has gone. Relatives and neighbours joined in with the killing and processing, the intestines cleaned by the women for sausages, the hams smoked slowly over the winter wood-burning fire in the wide, deep chimney.

We were here at the end of an era. I am glad I recorded it in Diggers and Dreamers. After the 1976 drought, when their well ran dry and they had to bring water in by tanker (our source never failed), mains water was piped in. That would have enabled them to machine-milk. What was then a mixed farm supporting and run by a family, is now a mechanised sheep-rearing operation, run by a one-armed man.

I say goodbye. He smiles his uncle’s gentle smile. A knowing smile? Or the peasant smile of one who is forever amazed but never surprised at the weird things people do – across the country? On a bike? On your own? Who knows. I want to shake his hand, feel his hand. But I have no reason to

I wheel my bike out. Past another stone cross, the same pierced circle. Was this a Cathar village? Were those interlinked lofts in Saint-Sernin, rather than for defence, in fact the secret hiding places and escape-routes of the parfaits (Cathar religious leaders)? How delighted Gabrielle would have been; for Fanjeaux was the home of Esclarmonde de Foix, the greatest of the parfaites; she had debated with Dominic himself. And the Cathar ‘cross’ perhaps represents, rather than the crucifixion, the radiance of the True Word from Christ …? (Already I am imagining the essays, the stories, the novel I might have written here …) There is writing on the cross, there are dates, under the moss. Did I really never remark it, clean it off, this mysterious cross, a few feet from our house, read what it said, find a message there? I sigh at how little we did, all the things we, I, didn’t do, how much I missed.

Cycling slowly back up the hill (and missing the dogs, who had pursued any vehicle out of the yard, biting at the tyres) I remember that the idea to move to the country came from working in the Ecology books section of Watkin’s esoteric bookshop, and reading the books that predicted that by 2000 we would run out of oil, and there would be an ecological crisis (another ‘take’ on the Millennium). And the magazines that showed you how to live self-sufficiently with very little effort. Moving to France, coming here, was because friends came before us. It was another version of ‘dropping out’. But we had no skills, not even the ability to work hard physically. All that came after I returned to England, trained as a carpenter, worked manually. I spent the rest of my working life learning the skills needed to succeed in the life I’d failed to live here.

If I had stayed, I would have been able to preserve the old ways, continue to learn the skills, maybe even encourage the neighbours to keep them going, making it worthwhile for them by attracting visitors. Visitors would be fascinated by hand-milking, Gaston’s demonstrations of old skills!

But that would turn them from farmers into performers. Isn’t this modern commercial farming more authentic?

Even so, I could have learned the forgotten history, found out – if they didn’t remember, there would have been stories from fathers, grandfathers – when they stopped growing rye on the terraces, when liming the acid soil of the rough, open land allowed them to plough and grow cereals, when chestnuts ceased to be the staple, what those first schools were like when they were beaten for speaking patois, how they lived under the Occupation …

And as I pass over the brow of the hill, and la Balme disappears behind me, I realise why I didn’t tell Didier who I am. He would have invited me for coffee, we would have ‘caught up’. But this journey is not about reconnecting. It is about registering. There is the world of then, as remembered in my head, and recorded, and invented in Diggers and Dreamers, the life I chose not to live. And there is the world of now, as I experience it. Any mixing of the two would blur this life, for which I need all the clarity I can get. I descend slowly, slowly, to Saint-Sernin.

And as I cross the new bridge, leaving Saint-Sernin, the words of a song, “a lot of water under the bridge, a lot of other stuff too. Don’t get up gentlemen, I’m only passing through …”

I take the turning to Coupiac, to the nearest camp site. And where I worked for a year in the abattoir.

I am cycling alongside the Rance, a gentle valley road, the small pale leaves of the poplars by the water glittering and shimmering in the evening sun like myriad butterflies dancing around the slender trunks. At Balaguier there is another small statue-menhir; this one’s sex has been changed, the female features replaced by male. With Gabrielle, I would have said this marks the victory of patriarchy over matriarchy, Zeus over the Mother Goddess, the arrival of the sky gods and their dominance, ever since, over the earth deities. She would have enthusiastically agreed.

At Plaisance there is a small pig-processing factory. A notice emphasises trust and tradition, the butcher travelling around the farms to collect the beasts individually. Perhaps it is to contrast their methods with Serre at Coupiac, where I worked, who shipped them in in big lorries, and was forever commercialising and industrialising. I leave the Rance at Plaisance, and head up to Coupiac.

Coupiac is built in the narrow valley of a tributary of the Rance. A good site for mills. There is an Occitan song, ‘la Copiaguesa’, ‘the Coupiac girl’, about the lovely girl at the pretty mill. The Occitan songs, often composed to old tunes, were written, a notice tells me, by ‘erudite locals’ in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, under the influence of the Félibrige, the Occitan revival movement founded by Frédéric Mistral. At the time when Occitan was being suppressed in the schools. The summer I met her, Gabrielle had visited the leaders of the Occitan movement in Toulouse, talked to the young singers and musicians who were doing for Languedoc what Alain Stivell had done for Bretagne.

There is a castle here, at Coupiac. More fortified house than castle, privately owned. I can imagine Gabrielle, with friends from Paris, with la Balme as their base, developing it as a new troubadour centre – not revivalist ‘folk group’ troubadours, but electric, electronic bands – Occitan rappers! I’m still dreaming of the life that didn’t happen.

The church was rebuilt in 1762, “to welcome the influx of pilgrims coming to venerate the relic of the Holy Veil.”

The fragment from the Virgin Mary’s veil had been hidden from the Protestants in the Wars of Religion, and the hiding place lost. It was rediscovered when the villagers dug at a place where a bull repeatedly pawed the earth, making ‘extraordinary moans’. It cured eye problems. I remember “Hermes, who as Mercurius, is also the Virgin Mary.” (John Michell, The Earth Spirit.) Stories!

Nearby is the square where in the nineteenth-century the locals brought their wheat to be threshed, using a communal horse-powered threshing-machine. The threshing-machines introduced in England in the 1830s resulted in riots and machine-breaking because they put men out of work. The same threshing-machine introduced here was welcomed, because it eased the labour of peasant farmers, and added an enjoyably communal occasion to their isolated lives. Same technology, different application, different effect.

I remember the mobile distillery, all gleaming tubes and spouting steam, coming after the vendange, parking here, and the locals bringing their grape-must to be distilled into their legal allowance of eau de vie.

But the narrow valley makes it susceptible to flooding. On the épicerie wall are two flood-level marks, one a foot from the ground, 1968, the other above the top of the door, in 1993. There is a note on the window saying that because of 28 November 2014 floods, the shop has moved to the village hall. Seven months later, it is still closed.

The village looks run-down, there are many places for sale, including the restaurant that advertised its ‘workers’ menu’ on the road from Albi, filled in those days with twenty or thirty abattoir workers every lunchtime. What has happened to the abattoir? I hope to find out tomorrow.

As I cycle through, following the signs to le camping, I see that the furniture factory is doing well.

It’s an unexpectedly attractive camp site, with chalets and a café, among trees and by a lake. After I’ve put up my tent and showered, I go to its café/bar/restaurant, La Popotte.

Brightly-painted trestle tables are laid out under an awning, overlooking the still lake, which is a coin of reflected sky amid dark trees, disturbed by the occasional water fowl then returning to its silvered stillness, and colouring and darkening slowly, as the light fades, to starlit black velvet.

The bar, on an empty campsite, outside a small village, in the remote uplands, has style, ambiance. It’s run by a young rasta-haired cook and a long-haired, friendly girl, and the decor, the music, the exotic burgers, give it the feel of a café hangout. How great, to have such a place, so close to la Balme! Again I’m imagining it here, back then, our friends, from all countries, meeting here for the shared celebrations, St John’s Eve coming up … But they aren’t us, they’re our children.

I ask who the band playing on the sound system is. Moriarty. A musical collective, born in France to American parents, named after Kerouac’s Dean Moriarty. It figures. Kavin says he’ll copy it if I have a memory stick with me. I drink wine, and Céline tells me how they come to be here. He is Belgian, she is from near Paris, they met in Switzerland. They got together. They took over this place in March. Are there enough people who share this style? Enough campers to make the site pay? Like the bistro-owner from Calais, at Vallon-en-Sully, they will only begin to know at the end of the season. Will they stay here, stay together, have a family? Who knows. I will never know. Just passing through.

But in the passing through, a delicious, expansive evening. As I ponder the list of exotic burgers, they say there is a dish of the day, a pot of dinde, slow-cooked with prunes and lemons. I think dinde is guinea fowl; I wouldn’t have had it if I’d remembered it’s turkey. But, no factory-farmed turkey this, a fine farmyard bird. The dish is fabulous. Tender, flavoursome meat, fragrant lemon sharpness, sweet, juicy prunes. A triumph. The wine flows, the music plays, and the evening slowly wraps itself around us. The dish is a rehearsal for St John’s Eve, in two day’s time, when he is cooking for forty. Oh, how I’d love to stay for that! I’m in a dream: well-fed, nicely wined, a warm evening, having been to la Balme, remembering the feu I attended in 1976, and back further, to my first time in France, fifty years ago …

They receive a phone call, and a couple turn up. She is beautiful. She enters, sits, ignores everyone, looks straight ahead. He is soft-faced, ordinary-looking. She is brittle, aloof, does not speak. He fusses around, asks her what she wants, relays it to Céline. His job is to arrange things perfectly for her, which he does nervously, willingly. It is time for me to leave. I pay, and, a little drunk, I stroll round the lake.

Shaded by the surrounding trees, open to the night sky, unmarked, a lake of mystery. To row out slowly on, to the centre. And then …?

Heading for my tent, I remember that Céline didn’t include the wine on my bill. I hurry across, she smiles her enormous smile, says, ‘you’re great!’, I hand her a note and, warmed by this gentle evening, I stumble through the dark to my tent.

Day 21: Coupiac to Albi, 48 miles.

The abattoir. The fallen maquisard. Along the Tarn. Ferraris and motor bikes. The tunnel. A chapel of healing. The Sage of Puech Cani. A view. Gilgamesh. Return along the Tarn

It is another very cold night, and I’m up early, walking into the village to warm up. But also to visit the abattoir, the pig factory, where I worked for a year.

We had left London and moved to rural France to live in peasant self-sufficiency. And yet I worked for a year on the production line of an industrial process in which squealing pigs were herded, stunned, bled, scalded, butchered and processed into products shrink-wrapped in plastic film printed with country scenes and a smiling girl in idealised peasant costume, ‘La Rouerguaise’, a celebration of locality, pays, a taste of the country brought to supermarkets by enormous lorries that battered their way between trees and over old stone bridges from this factory.

‘What goes into them?’ I asked Serge, who stood all day feeding an endless tube of plastic onto the machine that shot a stream of bright pink-dyed meat into it, which he twisted every few inches to form the sausages that mounted by him like coils of rope on a sailing ship. ‘Une pharmacie!’ he wailed. He had been a village butcher, killing and butchering the beasts as they came, sheep, cow, pig, whatever, one by one. He had been forced out of business and into the factory by EU and government regulations, and mechanised competition. The beasts that had come to his shop in a small trailer, or in the back of a 2CV, now arrived at the factory in a huge lorry. It had driven around all day, from farm to farm, and the pigs arrived parched, groggy, and sometimes dead.

My friends, who wrote for Undercurrents, who were anti-capitalist protesters, animal-rights activists, who squatted street farms, would have seen me as a mole, on the inside, able to gather information to attack the system, or at least stir up unrest, unionise and even recruit for the Revolution. It was here that I realised how little ideology, perhaps even principle, I have. We had no money. We needed money. I was here to work.

And it was here, that I learned how to work. How to put in a shift, learn a trade (boning hams!), employ manual skills, get on with blokes, endure and then make use of boredom. I learned to work a twelve-hour shift, humping carcasses, emptying frozen moulds in the freezer room at 7am, boning hams all day at a conveyor belt, heaving pig after bleeding pig into boiling water for two hours, cleaning up to be ready to do it all the again the next day, just the same. And then drive home, gathering bracken for compost on the way, work in the garden, and make, mend, fix an abandoned house, day after day.

Perhaps more important, it was here that I wrote two stories. One about employing zen, Tao, meditation methods, not in the formality of tea ceremonies or the stillness of meditation, but in the mundane, repetitive work of a production line. The other was about a simpleton who worked in the factory. That story was possible because I had learned how to be a quiet, almost invisible presence (having spent my life till then being schooled to be noisy, assertive, to stand out), to observe respectfully. And when to observe, and when to invent.

I learned, too, talking to Gilles, Suzanne, that for the factory workers, mostly young sons and daughters from paysan farms too small to support them, that this was a place to earn money while staying in their locality, to assert their independence, to joke and play tricks and work with their peer group, girls and boys, a liberation from the endless isolation of the farm. And jobs for the poor Portuguese immigrants.

I walk up the hill out of the village. The factory is still here. Silent on a Saturday. No name board, no collecting trucks, no delivery lorries. His name, the patron’s, is nowhere. It was, then, everywhere. Serre. It means talon, grip. The place was about him, it was the expression of his determination, hard work, his will. There wasn’t a job he couldn’t do, and better than anyone else. He would be on the production line, chivvying us, as the shepherds chivvied their sheep. They say most companies rise and fall in three generations. His, it seems, has come and gone in one. He must be long dead. No one took over. There is a Serre who runs a mobile butcher’s shop. His son? What was it for, all that hard, obsessive work? The factory is now owned by a Marseille company. It employs thirty. They still process pig products. But it is no longer an abattoir.

I walk back, make coffee, pack up, and am on the road by eight. I cycle through the silent village. Once the bar was the first place to open. Now only the boulangeries open early. This one is full of the warmth and sweet smell of fresh-baked pastries, and has delicious croissants and pains au chocolate, which I eat with relish.

Fortified, I head out on the empty road, alone in the morning freshness. I am cycling away from that time in my life, away from the world of Diggers and Dreamers. And away from the Meridian, further east.

But back on the Meridian trail, in search of one of the important figures in an early survey, who became ‘The Sage of Puech Cani’.

Over the empty top, I come upon a field of sheep! The first I have seen, in this land of sheep. Their shadows long on the sloping field, their presence highlights the emptiness. There are fields laid out neatly, rectangles of green and gold, all tidy and farmed, but with no animals. And no signs of life in the farms I pass, or the hamlets I cycle through. As if all living beings have been spirited away, a land emptied. Or perhaps it is a land made ready for the first man.

I pass a small memorial stone, ‘Here fell Raymond Crayssac, mortally wounded, for the liberation of France, 7 July 1944, aged 24 years.’ I wonder if Gaston knew him.

I descend to the Tarn. It’s a great river, wide, placid and green, somehow reassuring. Its forested slopes rise evenly on either side, its valley is varied, sinuous and very beautiful. I cycle along its bank, upstream, into the sun.

I know that the sage lies buried, the man I am looking for, at Saint-Cirice. And I know Saint-Cirice is on the other side of the river. But it isn’t on my map, and I can’t work out which bridge to cross to reach it.

There is a bridge across at Brousse-le-Château, one of the ‘Beautiful Villages of France’. Should I cross here? A dozen Ferraris, eleven red, one yellow, drive past me, in a concourse of drivers’ self-delight and passengers’ perfectly wind-blown hair. They cross the bridge and draw up in a line beneath the ramparts of the village, gun their engines throatily, and fall silent. It is their coffee time. Or an early stop for a leisurely lunch. And then a run of motor bikes passes me, twenty, thirty, men who wave briefly, along this side of the river. This is my sign. Four wheels bad, two wheels good. I follow the bikers.

I pass lengths of empty brick tunnel, horseshoe-shaped, overgrown. This is the railway that was never built. In 1880, with growing wealth from the industries of Roquefort, it was planned to extend the railway that ran from Roquefort to St Affrique, on to Albi, along the Dourdou and Tarn valleys. La Compagnie du Midi constructed the tunnels and bridges, many of each, zigzagging across the river. Expensive work. But the rails were never laid. It exists as a line on the map, with ghost tunnels and bridges. There are even signal boxes and station platforms. In places the road uses the bridges and tunnels. The next road bridge was built for the railway.

I cross the bridge. Immediately on the other side is a tunnel entrance, with traffic lights so the traffic alternates in each direction. It is a horseshoe-shaped blackness that is both a solid and a void, a wall I will hit and an emptiness that I will disappear into. It is the tunnel in The Vanishing. It is terrifying.

The lights change to green. But how long is the tunnel? How long before the lights change back and traffic starts thundering towards me, not expecting me, not noticing my puny light, blinding me, mowing me down? I must hurry. But within yards the tunnel has curved and the light is gone from behind me, and there is no light ahead. I am in the midst of a blackness that both buries me in suffocation, and retreats from me in a limitless invisible emptiness. The temperature drops. My light beam is a tiny dot on the road. But where are the sides? I will crash into the side, or cycle ever further out and be lost in an ever-expanding nothingness. My light illuminates a point on the road, but I can’t stand not knowing where the side is. I unclip it and shine it on the wall and wobble slowly along, the pale light-beam acting as my fingertips as I feel my way.

Cycling so slowly, so uncertainly, the tunnel curving, curving – how long is the tunnel, how long before the lights change? In these few seconds (minutes? hours?) I’ve lost all sense of time, of space. It is cold and I shiver. There is only a cold, clammy unknown. If I’m long in here, I’ll go mad, my thoughts flying out to be lost in emptiness, my being shrunk to a pinhead. I limp on for hours, beginning to wish for the approaching roar and blinding light to restore me to myself for one brief moment before annihilation. Then in the middle of this blackness that is both crushing and a void, an anger builds, a red fury erupts, I shout, ‘Bastard! Bastard!! Bastard!!!’

It means nothing. It means everything. I cycle on through black emptiness.

At last a paleness on the distant wall. It curves into the solid horseshoe of dazzling light, nothing to see. And then the road reappears. And the tunnel sides reappear. And I reappear, in all my simple form. I exit the tunnel, pass the traffic light. It is green.

Where am I? It is a favoured place, warm, full of sunlight, with birds singing. There is a terraced hillside of emerald grass, the ribbon of river is vivid blue, there are vines, a mosaic of hedged fields, and shaggy slopes of sweet chestnut trees. A buzzard soars high above in the blue. Where am I? Where is Saint-Cirice? I look back at the black mouth of the tunnel (how will I return through it?) – the tunnel it is called ‘Saint-Cirice’.

There is no village ahead, but there is a narrow lane up to the left, back over the top of the tunnel. I push my bike up, come to a cluster of houses, knock on a door, a woman comes to the door, half opens it. I ask, is there a village of Saint-Cirice? No, she says, there is no village, but there is a church; continue up the hill, follow the road round to the left, it’s there. Up and up I go, and at last, high above me, there is a simple chapel, silhouetted against the sky, reaching up.

The chapel was built by the Knights Hospitaller, a companion military order to the Templars, as a place of pilgrimage and refuge for those with mental illness. In the churchyard is the grave of a surveyor of the Meridian. Chapels are intensifiers of the upward connection to the divine; surveyors flatten the curved earth onto a rational plane. How did they come together?

‘The Sage of Puech Cani’, Jean-François Loiseleur-Deslongchamps was, in 1769, twenty-two years old, one of the idealistic, Enlightenment young men recruited as a surveyor on the triangulation from which the Cassini map of France would be drawn. It was the first modern, science-based map. Surveying was not, as Robb entertainingly describes, an easy job. Surveyors were attacked, their survey platforms destroyed by suspicious locals who spoke no French and saw the fancily-dressed young men squinting one-eyed through glass and metal mechanisms as sorcerers or, even worse, tax collectors. When looking for lodgings, everyone turned him away, even the local squire. At last a farmer allowed him to stay while he surveyed the area. One of the farmer’s six children, Marie-Jeanne, a thirteen-year-old shepherdess, was fascinated by him, and his work, helped him with it, learned from him. The survey moved on, but whenever he could, Jean-François returned. In 1774 they were married.

When the survey finished, they travelled around for work. But as she was always homesick, they returned to the Rouergue, and never left. He did various jobs, even working for a time as one of Trésaguet’s new road menders. At times they took church charity.

He was active in support of the Revolution, and in 1789 he became administrator of the new département of Aveyron, working in Rodez to unify the administration, money, weights and measures. He helped Méchain with the Meridian measurements that established the metre. He managed to survive the political changes emanating from Paris as the Revolution passed through its various phases – he was sacked and reinstated twice – before finally returning to his work as a surveyor in 1799.