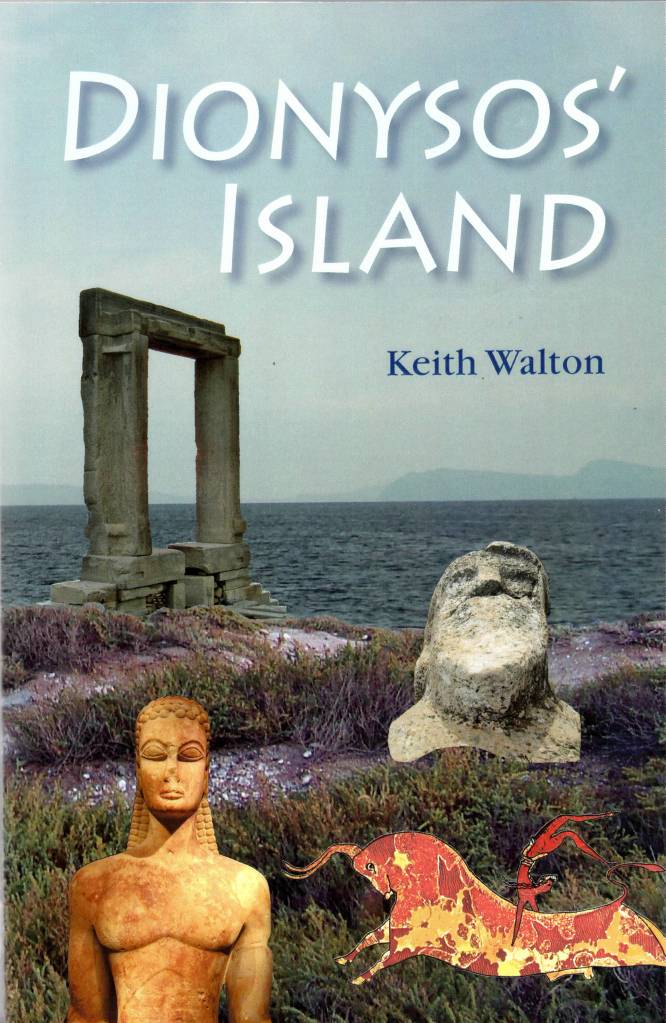

Set in 1971, two young men, dissatisfied with their lives, head for Greece on the long land and sea journey.

Richard, recovering after a traumatic affair with a student revolutionary, is hoping to recuperate in its classical calm and sun-filled clarity, while Simon seeks to empty himself in mountain walking.

For Richard, memories on the long journey by train and boat, and encounters with edgy, inspired artist Jacks, and knowledgable and mysterious Strawson, force him to continue questioning.

Simon travels to Crete, where he encounters a community reviving the Minoan ways and the spirit of Atlantis.

Richard’s time on an idyllic Cycladic island restores his equilibrium, but then chance – or is it fate? – takes him to Dionysos’ island, where a series of ever more extreme encounters with the art and deities of Greece’s past, surfacing in the present, bring him at last face to face with what he has been fleeing all along, and the question: are you ready to change your life?

This story of two young men’s first journeys into the Greek world, past and present, its landscape and literature, ideas and art, it affirms Lawrence Durrell’s: ‘Other countries may offer you discoveries in manners or lore or landscape; Greece offers you something harder – the discovery of yourself.’

401 pages £5 Available from brimstone-press.com

Contents

page numbers are of the print edition

Author’s Note

PART I : RICHARD’S JOURNEY TO ATHENS

1. Setting out 3

2. Leaving behind 5

3. Melanie at the fair 26

4. William Blake and the Arts Ball 40

5. The magic wave breaks 51

6. The Golden Arrow 55

7. With Nietzsche across France 60

8. Jacks, Bob Dylan and One Song Jukebox Number 1 78

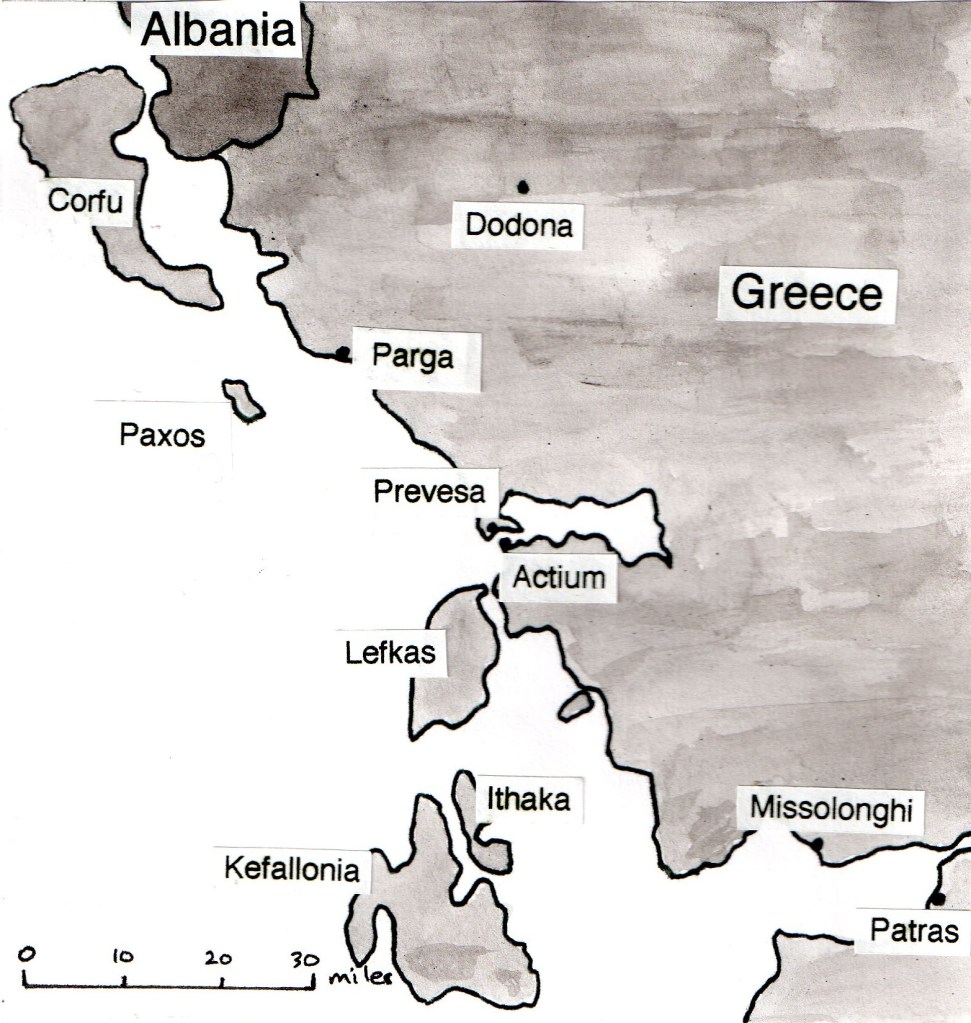

9. Ionian voices 85

10. “City of the Violet Crown” 95

11. Full moon over the Acropolis 100

PART II : SIMON’S ADVENTURES ON CRETE

1. Stepping eastward 107

2. On the boat into mystery 111

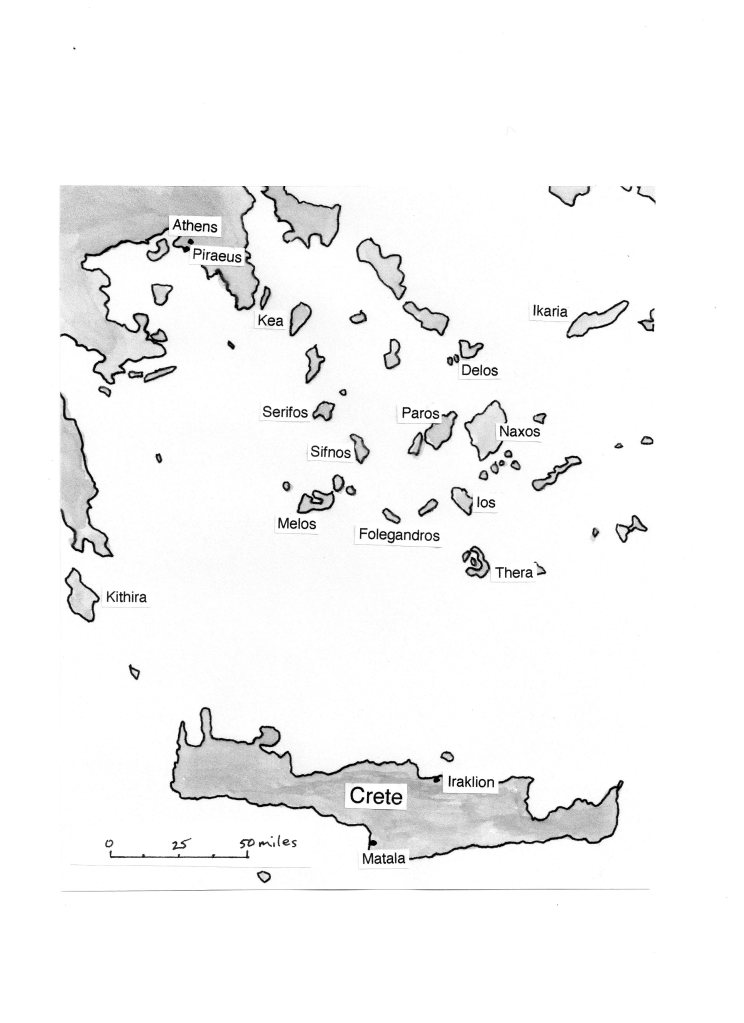

3. Matala and Atlantis 118

4. Passage through the painted caves 133

5. The Minoan inheritance 137

6. Dancing with Mandy 152

7. The labyrinth 160

8. Robing the priestess 169

9. Party time 176

10. Freddie explains 183

11. With Sally to Lasithi 187

12. Alone in Zeus’ cave 197

13. Plunging out of this world 204

PART III : RICHARD’S VOYAGE THROUGH THE CYCLADES

1. The old man and Kea 207

2. Seriphos and The Perseus Project 212

3. Siphnos and Melos 230

PART IV : IOS

1. Looking back on Ios 239

2. Greek friends 251

3. Dr George and the Cycladic figures 267

4. Arriving on Naxos 279

PART V : CONFRONTATION AND RESOLUTION ON NAXOS

1. Jacks’s story 285

2. To Apollo’s island 303

3. Paul’s story 319

4. Theseus, Ariadne and Dionysos 325

5. The secrets of Dionysos’ island 336

6. More secrets 354

7. Rites of passage 364

8. The gateway 382

Notes 392

Author’s Note

The details of Richard’s disappearance filtered through to me slowly. Or perhaps I filtered them slowly. I had lost touch, ceased to keep in touch with him several years before, having run out of patience with his lack of focus, his failure to get on. When getting on, one needs the company of those who are getting on, one needs to leave people behind.

He was last seen on Millennium night, as midnight struck, AD 2000.01.01, 00:00:01, :02, :03, swimming out towards Durdle Door, an arch of rock fifty yards from the Dorset shore. He was seen by chance, by a bivouacking fisherman, who happened to peep out of his little tent, pitched on the shingle, as a few desultory fireworks crackled over Lulworth, illuminating briefly the swimming figure. The sea was busy but not stormy, the fisherman reported, and the man was still swimming strongly when he zipped up his tent and returned to his radio and beer.

And that brought him back to me so clearly. For it was somehow characteristic of Richard, this dramatic even melodramatic act, calculated, and yet observed only by accident, his head bobbing through the waves, disappearing into the dark. The secret exhibitionist. He’s not there, he’s gone. Disappearing. Into death? Into a carefully prepared new life? Taking an unconsidered step into the unknown? I had no idea.

That might have been how it rested. He would have come to mind sometimes in quiet, evening moments, alone or with old friends, but gradually he would have faded, yet another of the unresolveds of one’s life. Then the box marked “GREECE 1966 –1999” arrived.

It came from a solicitor in Shaftesbury, with a note from Richard asking me to do what I could or would with it. ‘I’m sure there’s a book in there. But as you know I’m not very good at finishing things, and anyway I’m too close, it needs distance.

And perhaps I’ve actually done with it? It’d be your book, your copyright, “I renounce all rights” etc. It would be unfair to say I’m counting on you. I’m counting on you.’

There was a lot of it, I was busy, I put it aside, “The Unexamined File.”

When at last I opened the box, I was plunged into several worlds simultaneously that threw my well-ordered life into disarray, and set me on a task that would take far longer than I’d expected.

There were photographs, the earliest clear black and white, and then fading colour. How young we looked, so full of sap, insouciant, ready for anything. Girls I’d never known, one especially, hauntingly beautiful. There were illustrations, sketches and maps. There were layouts and flow charts with circled words, connected by lines and arrows multiplied to illegibility. Pages of diary entries, beginning in his round, schoolboyish certain hand (in fountain pen, permanent blue-black ink, his favourite an Osmiroid 65 with interchangeable nibs, bought in Boots … enough), through looser, more agitated writing, to word-processing print-outs. There were travel journals, short stories, paragraphs of fic- tion, notes and meditations on history, mythology, philosophy, pages of quotations …

As I lifted out layer after layer, laid them out on the carpet around me, I was unpacking Richard’s relationship with Greece. Where had he gone?

At first I thought only an exhibition could do justice to the complexity and interconnectedness of the material. (Not unlike, I realized later with a smile, his “Perseus Project.”) But that would simply have displayed it. He had asked me to resolve it, to repack it not into a box, but into a book. For him? Or had he really ‘done with it’? Was there something in it for me? Might he reappear if the book came out?

As I looked at, read through the material, I saw that Greece, its history, art and ideas, its landscape and people, its existence, the very idea of it, was something against which he measured himself. A home, like the home key in music, he could return to and depart from; a source to drink at; an omphalos to reconnect with. As one of his characters says, ‘Greece isn’t so much a place I visit as a state of being I enter into. I go there to be there.’ He always went open-eyed, open-hearted, innocent. Although a student, he was more a fan. He never stayed long, never mastered the language, he was always the stranger in a strange land, but a land that was uncannily familiar. He was a very unGreek hero, more Parsifal than Perseus.

But what to do with all this material? How to combine the story of a life with descriptions of places and expositions of myths, marry speculations on the development of religion and consciousness to encounters with disparate characters and strange utopian communities? A publisher asked, what is your market? A friend asked, who is it for?

When I, and Richard, first went to Greece, it was exotic and distant, and yet welcoming and familiar. We felt we’d ‘arrived home,’ however strange that home was. Aby Warburg wrote of the “mnemonic wave” of the flow and ebb of the Greek presence in European life and thought. Richard’s work is preoccupied with that wave, its strangeness and familiarity, and how it clarifies and illuminates our world.

At one point Richard mocks himself for writing that, having given up his career, he had ‘rented an empty corner shop in a poor part of the city, and set about finding myself.’ ‘Had I mislaid myself?’ he asks. And yet his whole life was a search for himself. He kept coming back to a sentence of Pindar’s, “become who you are.” The full line is, “Having learnt who you are, become who you are.” The learning occupied his life. Most of us ask, ‘what shall I do?’ He asked, ‘who am I?’ He slipped through the life of society, avoiding money, status, affiliation, attachments. Heroic individualism, or narcissistic irresponsibility? He once said, ‘I want to arrive at my death knowing how to live my life.’ ‘But your life will be over!’ I cried. He shrugged and smiled.

The Delphic gnothi seauton, “know thyself,” had three connotations for the ancients: know you are mortal, not as the gods; pay no attention to the multitude; reevaluate not the truth but established custom. He applied all three. But “know thyself” was supposed to be the beginning of life, not its end. And yet he had such a rich inner life, in the hemisphere of the bicameral mind (I use Jaynes’s terms) once inhabited and now abandoned by the gods. I don’t know.

I have used the form of the novel, folding and embedding as much of the disparate material I felt could reasonably be fitted into a narrative of his first visit to Greece in 1971. I have added notes to expand upon, reference and, I hope, clarify. It may seem odd that Simon’s story is inserted in the middle of Richard’s: it is there because it offers insights that illuminate Richard’s sub- sequent adventures; also it establishes narrative strands that will be explored in a second volume, Odysseus’ Island, set in 1999.

Part I : Richard’s journey to Athens

Chapter 1: Setting out

Doors slam, shrill whistle and waving flag, a last running man wrenches open the door, clambers in, pulls it shut, stands breathless, would-be nonchalant, hot in his suit, ignored by the forest of silent newspapers, drops the window open on its leather strap, gulps in air. Slow heave turns into motion: wheels creak, iron stanchions and the big round clock move past, a woman slides backwards, waving discretely, eyes full of longing, tears, not for me; at last the smoke-darkened glass roof releases us into the bright day, the train on which I commute each day so different today.

Clattering across the writhing knot of silver rails, abrupt sideways jerk as points marshal the two-axle bogies onto the train’s assigned track, settling into the reassuring clickety-click as the viaduct curves us past the sunlit public buildings and, in the dark below, the crumpled back-to-backs, Rinso and Bile Beans fading on terrace ends, figures held in fold-armed conversation, clothes lines high over cobbles, fat shirts waving. Goodbye.

I settle back, look down at my light holiday clothes, up at my rucksack, around at the men in dark suits, swaying together, like plants under water. They are me yesterday and in three weeks, and I am a scuba diver breaking up through the surface of the sea, tearing off my mask, breathing pure air.

As we go faster the train becomes lighter, smooth and timeless on the new welded rails, the used-up landscape scrolling past. But focus on an object in the middle distance, that tree for instance: the landscape beyond goes forward with us, keeping pace; while everything this side of it rushes backwards. Trainsition IIII. I showed the effect to Melanie on the train back from the Tate and she turned those blue-grey eyes on me, a look of wonder bathing me in attention, in a golden light that I took for granted, that I thought was part of me not a gift from her, until she left, her love a lost illumination.

Pinks, whites, greens stretch like brushstrokes past the window, telephone wires rise and dip like birds, bridges slam past. The train is rising, the touch of satin wheel to polished rail is now a faint kiss, both still at the point of touching, and we are flying along, approaching the moment of separation … How often, on my journey to work, as the train went faster and the sun rose red through black colliery winding gear I’d have a moment of clarity that would have, if the train had plunged through to revelation or oblivion (it didn’t matter which), become a moment of consummation. Each day, as the brakes were applied harshly, I was jerked back into the carriage and had to pour myself back into the approximation of a person, put on a recognized face, step down at my station and walk to the office. Not today. Today my thoughts can stay free, floating, the London train is the train to London, the first stage on my journey to Greece. As my office in the Planning Department approaches, passes, familiar figures fixed, disappears behind, I float, smiling.

Chapter 2: Leaving behind

Settling into the journey across the stricken landscape, spoil heaps formed into giant black blancmanges, soon to be covered in white plastic, artificial ski slopes, as per our policy document “Recreation Facilities for the Age of Leisure”, merry miners skiing in bobble hats and scarves, cheery waves. Hello. Goodbye.I spread my papers on the table, prepare to look through my notes on Greece. But find myself instead, after buying tea from the trolley, going over the events of the morning.

I’m used to the janus of expectation and nostalgia when going away: my head full of the wonders and perfections of my destination, the new world that’s waiting to receive me and change my life; at the same time a sentimental bloom on everything I’m leaving as I walk to the bus stop, the trail of ivy and a single pink flower in the sunlit graveyard, “Maggie May” playing from the flat above the newsagent’s with a girl’s warbley voice singing along (who is she?), even the stale beer and cigarette smell from our pub where the old woman is stoning the step.

But at the bus stop I was aware of how different I was from those around me. But isn’t that me yesterday, and again in three weeks? And crossing the city centre to the station, head up, my rucksack hitched high, stepping out, seeing shuffling, preoccupied figures, eyes far away in ambition or deep in dream, alien to me this world, wanting to lay my hand on this man’s arm hold him, say, ‘see, that pretty girl, in a yellow skirt and a blue top, twirling her pink bag in the sunshine, carefree and gay having kissed her new boyfriend, the twirling bag sending (oh no!) the black bowler spinning from (I say!) the solicitor’s head, see it caught nonchalantly, without breaking step (owzat?) by the traffic warden, see them all stop, amazed, laugh, exchange, pass on, the moment swallowed up, unobserved, gone …’ Daily tide, flowing in to flow out, pebbles rattled in, rattled out, a little smoother each day, I wanted to cry, ‘you’re moving, but where are you going?’ But of course I was directing the cry at myself.

It disturbs me because in the six months I’ve been in my job I’ve convinced myself that I can be in it but not of it, that as I strip off my grey suit each day (in the toilet on the train home, put on paisley shirt and stonewashed jeans so I can step off the train as if I haven’t been to work) I am shedding my role, returning to being – me. While realizing that each day I am becoming more involved, being given and taking responsibility, flattered by authority, compromising my integrity in the interests of loyalty and career. “Lend yourself to me for one brief deceitful day, and then through all your days you will be called most upright of men,” old hand Odysseus to neophyte Neoptolemus. ‘You have to see the bigger picture, Richard, means and ends,’ my section leader to me. The mask I put on each day sticking more firmly so that one day, howl as I might (except, even worse, I won’t notice, I’ll be the frog in the heating water) it will not come off, I will be it. But the hypocrisy of expecting the comfort of belonging without the responsibility of participating.

And yet six months ago I’d thought that, in one weekend, I’d resolved my life.

After I’d given up The Project, when I had become like a statue of wetted sand that is drying and beginning to blow away, when the lives of my contemporaries, that I’d so mocked when I walked away, were suddenly, my nose pressed against the glass, looking in, infinitely desirable, I had, with considerable effort managed to package my dispersed self back into the role “Town Planner” sufficiently well to be offered a job. And wasn’t this what I’d wanted to do, been trained to do? Wasn’t I, after a skittish six months, returning to the fold?

I accepted the job, in the county town just a few miles away, on the main train line, and took the bus to my home town. Yet another of my journeys across the Pennines. Remembering arriving for the first time in the city from home, on my scooter, descending from the purple moors, the conurbation laid out before me, a dramatic vista of churning clouds and shafts of sunlight picking out the tall chimneys and big factories and long red brick terraces of the world I would remake, the black tower of the town hall and the white tower of the university that were the twin poles of my future, waiting for me, a new graduate heading for a postgraduate course, a cry of ‘yes!’ – I was a knight on a charger – as I accelerated down the long hill.

And the first weeks so comprehensively good that I took it all complacently for granted. Hubris (‘arrogance and presumption’), and all that followed. I returned home the first Christmas charred and in shock. I was Crow, flying the black flag of myself.

Whereas this return, two and a half years later, six months ago, was quiet and circumspect, and I had a job, which would reassure my mother, who asked only that I ‘be happy’ (as if this was a career option), and my father, who could now complacently resume living vicariously through me.

How pleasant, at first, the warmth of the familiar and given of the small terraced house, the smell of freshly washed clothes airing on the maiden by the fire, the roast chicken meal (on a Friday! Truly a fatted-calf moment), the apple pie and evaporated milk. And how quickly it turned to suffocation as, like programmed automata, when the clock struck they turned on the television, switched off the light, and settled in their chairs, the blue pictures flickering on childlike faces.

So I went to the pub in town where we used meet in the college vacations.

But it was term time, and anyway they were all, my contemporaries, now settled in new lives and distant places. Perhaps I just wanted a chance to sit among ghosts. Of friends I’d paid too little attention to. Of girls who had passed, a moment of recognition before passing on.

On the other side of the mahogany and frosted-glass partition that divided this lounge bar from that public bar, where drank my best friends at primary school, who had failed the eleven plus, who I’d never spoken to since. And where, when I was in here with college friends, I’d glimpse my brother in the fancy etched mirror behind the coloured bottles at the back of the bar, our eyes sometimes meeting. Like Joyce I had thrown in my lot, aligned myself with my education (called, in my case, liberal-humanist, but just as jesuitical). Like him I’d doubted. But while he had escaped from it “alone, unheeded, happy and near the wild heart of life,” I had walked out grandly, then fallen apart, panicked, and scrambled back inside the rule.

I waited, as I sank into the melancholy of the solitary drinker, for a sign. The door was hesitantly pushed open, and Ursula looked nervously in, saw me, her face flooding with relief, ‘Richard!’ she cried, and rushed over.

Ursula and I had gone out together at school, in that serious, married-couple way that some kids do, bypassing (or insulating within ourselves) the desires, extravagances and originalities of adolescence, conforming to a given notion of how to behave, who to be.

We would sit at opposite ends of the big table in her family’s kitchen doing homework, go for long walks hand in hand, unstoppable in our talkative self-absorption, setting the world to rights, each the other’s ideal audience. We chose with perfect seriousness the cottage we would renovate to our taste and live in, and decided which empty warehouse on the quay we would develop as an arts centre. We fumbled gravely in the dark of our front room, skin blue-lit by the street light, going only so far, saving ourselves for each other.

With rings of twisted grass and promises of fidelity we went off to our separate universities. It lasted a term, as she rebelled against everything, had a spectacular affair with the union president that ended badly, followed by two years of outrageous behaviour, a poor, scrambled degree, primary-school teaching. Whereas for me, university was the seminary of a new faith, of which my god was rationalism and my catechism the scientific method, the certainties of which covered over the inexplicables of my life. And yet something amiss, so that when I started my postgraduate Town Planning course, I pinned on my wall: “one knows, all the time, that one’s life is not right, at the source.” Which I guess is how the whole Melanie thing could happen.

But that was in the past. Sat opposite each other in the pub that night six months ago, Ursula and I were happy to occlude the last six years and connect directly those guileless, optimistic seventeen-year-olds to our bruised but still hopeful present selves. Her hair, once extravagantly long, then Jean Seberg short, was now a careful mid-length. Her sparky quickness had matured into a cool intelligence, her humour now tinged with a gentle irony. Her eyes were as bright and watchful as ever, and I’d quite forgotten how pretty she was, a girl I’d be happy to be seen with. We talked about films, books, music, smiled at how in step our tastes had developed. We enjoyed mocking our younger selves: ‘talk about old before our time!’ ‘“I was so much older then …”’ ‘Exactly! Such prigs!’ But touched too by the shared memory of them, us, two earnest, honest innocent kids who we missed. All this conveyed in words, silences, looks, touches. After one silence, looking down, she looked up, grinned, shook her head, said:

‘I can’t believe this is happening!’

‘Perhaps this is meant to be?’

‘Perhaps. Yes. Yes.’

I walked her home, arm in arm, that familiar walk along the canal, past the hospital, our shadows behind then stretching ahead as we passed each street light, inventing the lives that were going on behind each lighted window, as we’d always done, becoming increasingly baroque as we strove to outdo each other. We arranged to meet on Sunday – her brother was getting married on the Saturday – and she kissed my cheek softly and squeezed my arm.

I went to my special place, from where for years I’d observed the town unseen, where I could release my thoughts.

A train pulled slowly out of the station, its wheels spinning as it struggled for traction – how often I’d heard that from my bed. The white marble and green copper memorial to a dead wife, our Taj Mahal, was ghostly above the town. The town hall clocks struck the hour, one light and quick, from the town’s eighteenth-century merchant prosperity (Handel), one slow and portentous, built by a Victorian industrial magnate (Elgar). I imagined my parents in their long-shared bed, my newlywed brother and his wife in theirs. I remembered with a smile how once Ursula and I had crept into her parents’ bedroom, looked with awe at the big mahogany bed, the piles of books on bedside tables, the art nouveau reading lamps, and lain carefully on it, side by side, fingers touching, wondering if we’d ever grow up to fill such a bed.

Perhaps – what a thought! – we had? We could pick up where we’d left off, each containing and profiting from our experiences in the years between, all the time our relationship having stayed fresh. We get on well. We fit. I can imagine our children. We can be happy. After the stumbles and detours, we can pick ourselves up and walk along the road together, once more hand in hand.

So it was the new optimism about my future that allowed me a (last?) Saturday morning of unabashed nostalgia.

I walked through the miscellaneous smells of the covered market, past the sweets stall where my brother and I had bought liquorice root and coltsfoot candy, the fishmongers’ stalls with their uncanny fish and wriggling eels that always made me shiver, the butchers’ stalls smelling of sawdust and blood, the sausage stall with the man with fingers like sausages. On to Woolworth’s where we would wander round, just looking, buy cheap sweets, and steal things, partly for the daring, but also to have, to possess. Having little, objects became fetishes. I had a tin box I hid behind a stone in the yard wall. I’d get it out and look at the things I’d stolen, that had to be hidden otherwise my parents would ask where I’d got them, my secrets, and promises of other lives. Round the shops, seeing shop assistants I remembered, now shorter and wider, as if they’d settled over the years. And greyer. Shops closed down: “Smokers’ Requisites and Tobaccos – Try Our Dark Shag.” And new ones opened, “Whole Foods and Natural Products.” The new shopping centre built on top of where we’d lived, my tin box buried deep.

And then into the reference library where, at grammar school, a few of us serious working-class kids went to study (the middle-class kids had rooms of their own). Four walls of books. The whole of knowledge, classified by the Dewey Decimal system, so you could find out anything. Relieved that it was all there. Daunted by the scale of the task of knowing it all. The everyday goings-on in the market square outside were so ordinary compared to what was available and happening inside this cave of treasures, this tower of learning (“learning” a delicious word as both verb and noun). I would look through the big art books, “750: Painting & Paintings”. But sometimes in here felt like a prison, and that world outside, seen through bars, looked enticingly real, and getting ever less accessible.

At eleven o’clock we’d close our books in unison with a slam, ‘shsh!’ from the disapproving librarian, grin and walk round, as I did that Saturday, to Stan’s coffee bar. It was run by Jim. No one knew who Stan was. It was in a narrow street, up steep dark stairs. It had no juke box, but a record player and a pile of blues and jazz LPs, and maybe someone noodling on a guitar. Tepid coffee was served in shallow glass cups. The pre-dip art school crowd would sit on that side, the grammar school crowd on this. There’d be moans and catcalls back and forth at what the other side got played, but little connecting.

But Penny and I did connect, in our hesitant, demure way. Sometimes, when we were close, to provoke we’d sit on either side of the line and hold hands across it. Romeo and Juliet. That was before I was going out with Ursula, during my lower-sixth flirtation with art. The last time I’d seen Penny, in here, a couple of months before, when The Project was going well and I was high with it, she’d said, ‘next time, you’ll be sitting on this side.’ But the next time, this time – for, yes, there she was, smiling that ‘is this believable?’ smile – when she patted the seat on that side, I shook my head and sat down on this.

I’d known Penny since ‘O’ level. Art clashed with Latin, so I went to evening classes at the art school. I discovered charcoal and oil paint, the sensuous experience of handling them. And a different sort of education, encouraging creativity and developing self-expression. While I spent my days working my way through a curriculum. ‘Do you know what a “curriculum” is?’ she’d asked, eyes flashing, when I said she never seemed to settle to learning anything, was always darting from this to that. ‘It’s a racing chariot. And what you do is go round in circles, winning prizes and getting nowhere.’ It was a punning response, but in her eyes there was sadness that I was missing something important.

So, we inhabited different worlds, liked each other, would come upon each other when home from university and art college, sometimes almost get together (a New Year’s Eve party, an Easter walk along the river), always just miss.

In the nine years my appearance had changed minimally – school blazer to tweed jacket to suede casual, grey flannels to rust cords to faded jeans, polished shoes to desert boots to coloured plimsolls, my hair half an inch longer each year – while she had gone through transformations. And changing not just her appearance and behaviour, even her character, but her nature. So at sixteen she was an existential beat, dressed in black, singing Juliette Greco songs, into Artaud and Dubuffet, her paintings scumbled and dark, her boyfriend a depressive who’d failed as a poet in Paris and was now a journalist marooned on the local paper, writing his own never-ending Howl. Suddenly she was a dolly bird with a dandelion afro, in colourful and geometrical dresses and knee-length white boots, waving from a pop promoter’s E-type, taking objects and images from every source to put in large, bright, busy, fun collages. Then another change, her hair long and red, her clothes swirling, in rich, natural dyes, sandals, influences of folk art, especially Balkan in her clear, simple pictures, now with a bearded builder of gypsy caravans. When I charged her with a pick and mix approach to art, disrespect in wrenching objects and images out of their contexts and relationships, she let fly, saying, no, she was resisting and subverting the art historians who compartmentalize art and arrange it into a simplistic sequence of “great artists”:

‘Art is a spatial field, not a temporal sequence,’ she spat.

‘But where are you in all this?’ I demanded. She looked at me, as if trying to work out what I might understand, how to pitch her response, said patiently:

‘The self is a construct of the mind, a defence mechanism, a comforting sense of order and continuity. But to really learn, you have to enter, become, be. It isn’t about hooking ducks at the fair and putting them in a row, but about going into foreign places. Don’t stand on the shoulders of giants – follow the pearl fishers down. Dissolution precedes resolution. You have to stay out of your head. There’s only now. You’re a particle, and now is the wave you ride. Do what’s now, otherwise it’s not life, it’s recollection. We’re not Alice following the rabbit – we’re Alice and the rabbit, at the same time. It’s not easy.’

It wasn’t easy. The last time I’d seen her, in here, those few months before, when I was high on my Project, she’d been grey, blurred, wretched, ground down by a lousy teaching job and all her work coming to nothing.

And now? Well. I was sitting beside, looking into, the sun-filled, smiling face of a woman, beautiful, clear, resolved. Her clothes, her style carried elements of the styles she’d adopted so single-mindedly, now mutually echoing, dynamically harmonizing, into her own, individual look. And her face, that for all its prettiness had always seemed provisional, changing with circumstance, had settled into a fine beauty. She had found herself.

She of course would have none of this:

‘The self is a construct of thought. If you act wholly, selflessly, you experience purely. And now I have so many of those experiences to call on – and more all the time – that they arrive without getting tangled up in all that ‘self’ business. I am what I do. I have no inner life. The unexamined life is life itself,’ she laughed. Then, quietly: ‘And it isn’t easy.’ She looked at me keenly, as if trying to see what, if any, of this I understood, resumed:

‘I’m going to Cornwall. This is a last-day tour of my past. I know, revisiting isn’t me, is it? But this really is goodbye to all that. Someone’s backing me. I’ve no idea if what I do is “art” – not even sure if art exists anymore. There’s just events and stuff. I do stuff. I make Patrick Heron lampshades, Barbara Hepworth ashtrays – this is a Peter Lanyon!’ pointing at her multicoloured dress. ‘They’re all one-offs, handmade. Does that make them art? What if someone else made them and I signed them? Or I did multiples? No idea.

‘But you, how’s the Project going? It sounded so exciting – the Fisher King, and all that! – you really must keep at it. Come to St Ives! Do it there! There’s a place next to mine, you could rent it for nothing, work in the bars in summer. Are you still singing, playing guitar? Life is stuff and events – I do events, too. We could work together, you’d be the word guy, we’d be The Chums, end of the pier. Of course we’d have to build a pier first. We could do that.’ All in a hectic torrent.

To get a word in, I said:

‘Do you know what a pier is?’

‘A disappointed bridge,’ she replied. I was amazed, Mr Wilkins had told us that.

‘Who told you?’

‘No one,’ she said, adding pointedly, ‘I read the book.’ Then:

‘I’m leaving tonight on the eleven o’clock coach. Amazing to see you. See you?’ and was gone.

Timing. What would I have done if this had happened a month before, before I’d started cramming to get a planning job? I’ve no idea. Not even a sensible question. Whatever, I was at the bus station just before eleven, but watching from the shadows.

The last buses from the seaside town’s dances disgorged the celebrants, all drunk, variously sleepy, euphoric, angry, lost. A couple, wrapped around each other, keeping alight the flame of the evening between them. A brief, fierce scuffle, broken up by the bus conductor. A woman shouting after a man slouching quickly away, ‘yer ought ter be fuckin’ ashamed of yersel, what yer did, fuckin’ ashamed!’ pursuing him, throwing a pink stiletto shoe at him, it bounced off his dark back, he hurried on head down, she collapsed into her mates’ arms, they led her away. Soon all were gone, the buses parked up, close, dark, like slumbering beasts.

The long-distance coaches pulled in and pulled out, figures, alone, travelling into the dark, to new starts or disappearances without trace, she’s leaving home, bye bye, faces looking out, ghostly. I watched Penny’s bags being loaded. With one foot on the step she stopped, looked round, then climbed aboard. I couldn’t see where she sat. The coach pulled out. The station lights went off. I went home.

All of that had shrunk to a far corner of my mind by the time I was walking briskly through the warm sunshine to Ursula’s house on the Sunday.

I pressed the Edwardian bell-push by the heavy brown door under the coloured-glass transom window of the house I’d wished I’d been born in, with its reproductions of real works of art, its lived-in casualness, its shelves of old books. We had Tretchikoff, my mother polishing the emptiness, my father saying why have old books when you can get the latest at the library. I was let in through the dark anaglypta-papered hall into the sitting room where her father was torpidly digesting, the newspaper across his stomach, her mother crocheting. I found her teacher-father’s conversation, that I remembered as sharp and penetrating, now a thoughtless ragbag of clichés and received opinions, untouched by the contemporary. And her mother was no longer the interesting bohemian, but careless and unkempt. And why, I wondered, didn’t they risk their own judgements and buy contemporary art, rather than reproductions of “the masters”? All this I noted only in order to vow that we would not slump into such complacency. But I did notice that Ursula stiffened at even the slightest criticism of her parents.

We walked old walks, revisited old places, recalled our naivety and optimism nostalgically. One by one we placed the lost images back in the memory album, beginning the process of restoring a shared remembering. For weren’t we the same people, connecting back across an abyss, picking up dropped stitches, knitting our lives together once more, covering the abyss over?

It was spring and there were flowers and fat buds everywhere, and birds clamorous and quick, a buzz of new life in the air. We introduced topics and interests we’d added in the intervening years, carefully and sensitively, to draw the other in. We took each other to unexpected places. She led me through a dark wood to a sudden blaze of bluebells, the air full of their fugitive scent under our feet. She walked barefoot, I liked that. And I walked her along the old railway embankment by the estuary, where the bright light dazzled off the mudflats, the brown river flowed strongly, and sharp-edged birds, cutting through the clear air, swooped and flashed. She was entranced. We were a good fit.

We were sauntering along the canal towards her house, smiling at the ducks snappishly quarrelling, companionable, about to complete the parabola of reconnection. Physical too, for twice we had stood and embraced, remembering bodies, and kissed, remembering lips. When Ursula stopped suddenly. We were under one of the heavy stone bridges, the canal narrow, stone-edged, dark and deep, and she stood in front of me, hands on my arms, serious, her face suddenly uncanny in the uplight of rippling reflections that played too on the low curved arch. Water dripped. Her voice was echoey and strange, stopping and starting, urgent:

‘You are serious, aren’t you? You must be serious. It’s just that … There have been too many … I couldn’t take it if … I can trust you? Can’t I?’ almost pleading.

‘Of course. Honest. Little fingers,’ holding my hand out for our old gesture of fidelity, then wrapping her in my arms.

And so began a new era in my life, with a proper job and a steady, grown-up relationship, how life was supposed to be. I worked during the week at curbing my flights of fancy, being practical, and adapting to the frustrations and longueurs of the office. We spent weekends together, at her place or mine, constructing a shared life, integrating with other couples. She applied for and got a job in my city, and would begin term while I was away. On my return we would look for a flat together.

But too often, as the summer advanced, I found my nose pressed against the glass, looking out, at hitchhikers or cyclists, yearning for the freedom out there.

This trip to Greece, originally planned for the vacation between university and planning school, is supposed to be another reconnection, a knitting across the abyss, back to stability. Instead it’s stirring up all sorts of forgotten thoughts and feelings.

x x x

My notes on Greece are spread out on the table in front of me. I should be reading them. The train accelerates, almost free, then brakes hard for each dull town. I thought I would pass through this used-up landscape floating, emptied, filling up with Greece. Instead, all this remembering.

In the summer of my second year at university I went to France, Provence, my first time abroad. I went in search of Van Gogh, found Cézanne, a new world of dizzying clarity, and in the heat and dust and blueness, for some reason imagined myself in Greece. I mentioned this to a serious American, staying at the youth hostel in Arles, who showed me a letter of Hölderlin’s, written about France: “The violent element, the fire of the sky, stirred me continually . . . Apollo struck me . . . the south made me better acquainted with the true essence of the Greeks.” Hölderlin, passionate about Greece, never got there. I would. It was the next step.

After graduation I got a summer job labouring on the new bypass. The fresh-cut line was high above the town, with the purple moors sweeping emptily away to the east, and to the west, beyond the smoke-dark town, the pastel seaside resort and the sparkling sea. Each day I worked, stripped to the waist, hard work with pick and shovel, not up to the regular navvies but trying hard, tolerated, toughening up, a simplified world of repetitive labour, distant vistas, absence of conversation (talk like splitting stones) that allowed the formal structures of thought to dissolve, the silt of accumulated study to leach away, the chattering voices to fall silent, my mind to become gloriously empty and available. And the wages paid for my ticket to Greece.

Each evening, as my parents shut out the light and sat entranced by Emergency Ward 10 and Coronation Street, I was upstairs at my desk (now wonderfully empty of coursework), by the open window, bathed in the evening sun and evening sounds, reading the history, myths, and travellers’ tales of Greece.

Those first certainties are on the table before me, in my neat, round hand, as the train rushes south, the assertions and rhetorical flourishes that created my first picture of Greece, in my age of innocence: “The glory that was Greece.” “The Greeks looked life in the face.” “Of all peoples, the Greeks have dreamt the dream of life the best.” “The home of the gods, gods of human proportion, created out of the human spirit.” “If Greek civilization had not been invented, we would not have become fully conscious.” “The Greeks saw life steadily and saw it whole.” “Greece stands eternally at the threshold of the new life.” Stirring stuff. The world of Homer, Aeschylus, Phidias, Plato. The origin of our civilization, the source of our self-realization. Surely there, at the source, my doubts could be quieted; from there I could return, clarified and reassured, ready to move confidently forward.

It never happened. A confusion over dates meant I had to cancel my booking to begin my postgraduate course. And by the time the opportunity came again, three years later, now, so much had, has changed.

And so we gathered, smart graduates in geography, engineering, sociology, architecture, fine art; physical scientists and social scientists, certain of our intellectual objectivity, our ability to analyze and synthesize, armed with the latest theories and techniques, dedicated to applying science to society. We would create, with utility and beauty, practicality and idealism (even, whisper it, utopianism), a better environment, and therefore a better world.

On the first morning, gathered in the empty studio that we knew we would soon fill with our grand plans, we rubbished the syllabus, and determined that we would create an accurately descriptive and working simulation model of the conurbation. Using central place, gravity flow, diffusion surface, social structure, stochastic process and traffic potential theories, and the university computer, we would develop a simulation model of reality in which the effect of different policies could be tested. Planning would be based not on subjective opinions but on objective scientific principles.

I left the studio, my brain enlivened by our revolutionary discussions, my experience of the complicated conurbation clarified by the knowledge that its form and functioning would soon be made comprehensible through the simulation we would create.

I was renting a back-to-back in a solid area, close to but not in the student quarter, sharing with a friend who was doing research. The others were going for a celebration meal, but I wanted to ground myself in my new locality. So I spent the evening hearing companionably the families knocking about on three sides of the small living room, as I read The Uses of Literacy.

At ten o’clock I yawned and stretched. I could meet the others at the student pub. Or I could, full of Hoggart, why not, go to my local? My first local. Where was it?

I sauntered along the street in the mild September air, past lit windows, undrawn curtains, domestic lives, to the road at the end that swept down into the valley, and a shock. In front of me, beyond the road, was a vast emptiness. The cobbled streets and worn pavements were still there, but the houses had been removed, as if from a giant Monopoly board. A couple of distant fires, with sinister dark figures round them, added to the sense of desolation. Just one isolated building remained, a small pub, dimly lit, a gas light outside, The Omdurman. I crossed the road and entered.

I squeezed past a woman in pinafore and slippers collecting a jug of beer from the off-sales hatch, pushed open the door marked “Saloon”, and realized too late that I had walked into an alien world that I didn’t know how to function in. Where to look? who to speak to? as I waded endlessly through the sudden silence, the hostile looks, at last reached the mahogany bar, grabbed it, and ordered a pint of bitter.

I stood, hanging onto the bar, sipping the beer, a lost face in front of me in the mirror and eyes boring into my back. Should I stay standing? Find a seat? With others? On my own?

A big man next me laughed loudly and stepped back heavily onto my foot. ‘I say …!’ I yelped, and he spilled his drink. He turned slowly, flushed face, his fists balling, ready, ‘what say, luv?’ Not aggressively, but a question requiring an answer. Was this the gunfighter moment? Was I Shane?

A hand soft on my shoulder. ‘He says, Gerry, that he’s very sorry he carelessly put his foot under yours, and can he buy you a pint?’

‘Aye, aye, mild, ta,’ said Gerry, lifting his glass in acknowledgement, then, ‘yorright, Bruce?’

‘Tip top, Gerry. And we’re on for Saturday?’ Gerry nodded, at Bruce, at me, turned back round. I paid for the pint and followed my saviour to a table in the corner.

‘Sorry about that,’ Bruce said as we sat down. ‘But you seemed less than au fait with the Omdurman way. Gerry’s a good lad, but there’s not many back and forths before it’s fists. Great for getting building materials, though.’

He was confident, affable, hair in an Eric Clapton affro. He introduced the others. Spence, with his lank black hair, wispy moustache and beard, his glittering eyes, needed only a bomb with a fizzing fuse to be the archetypal anarchist. Steffie, her hair tied in an assortment of ribbons, wearing clashing charity shop clothes, was quick and aggressive. And, hidden behind a curtain of fair hair from which she would emerge, when she put her head up, with large, clear, Caroline Hester blue-grey eyes and an uncertain smile, a face across which moods passed like clouds in a blue sky, Melanie.

Asked about myself, I said I was renting locally. They exchanged meaningful looks, and Steffie snorted derisively. ‘You see,’ Bruce explained patiently, ‘the landlords put in a few sticks of furniture so the rent’s decontrolled, taking the houses out of the reach of the locals, then rent to people like you with no stake in the local community. What are you studying?’ My reply produced another silence, then Spence hissed, ‘so, your lot did this?’ arm encompassing the desolation around the pub. I explained that the houses were substandard – it was slum clearance, after all – and those moved out were given new, high-spec subsidized council flats. Anyway, our job as technocrats was to propose, for the democratic process to dispose. Steffie let rip: upgrading would be cheaper, could be done by jobbing builders, but the big firms liked new developments, and they had the councillors in their pockets; breaking up the neighbourhoods atomized and disempowered the working class; as the factories were removed from the valley bottom to the trading estates, the river and canal were being cleaned up, a linear park created, making this a desirable area where, surprise, surprise, middle-class housing would soon be built, while the working class were stuck out on the ring road, in tower blocks, with lousy public transport so they had to buy cars they couldn’t afford; it wasn’t a democracy but an elected oligarchy in which the oligarchs controlled education and the media and so the elections. She at last stopped, glowered. Bruce added, ‘as Tolstoy said, “the truth is that the state is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens.”’

‘But you live here!’ I protested. Smiles all round. Spence said, ‘we squat. When families are moved out, we move in, reconnect the services. For every house we live in, we make two available for those in need. Real politics is guerilla warfare – don’t you see that the eleven plus is just a tool of the ruling classes, designed to cream off the clever to strengthen their stock and weaken the working class? Made bourgeois by the education system, bought off, you’re doing their work and betraying your class.’

‘Not so,’ I said, ‘we’re a working-class influence in the corridors of power. Anyway, class war’s old hat, the class system is withering away, it’s a meritocracy now. What we need now are technological solutions.’

The argument went back and forth. Bruce was smiling, enjoying the cut and thrust, while Spence and Steffie were taking it personally. Melanie was silently watching. At some point I asked what were they, were they anarchists? Bruce replied seriously:

‘We’re liberators. We’re at art school so I guess that makes us art students. But for us art and politics are aspects of the same process of liberation. We’re having an “Event” on Friday – why not come?’

I left long after closing time, let out of the back door of the blacked-out pub, feeling deliciously nefarious. The fires had died down, and most of the houses were dark. I should have gone home to bed, but I was so full of the events of the day, all mixed up, that I walked up the road to the moor, an open area laid out as a park, and sat on a bench overlooking the city and beyond it the conurbation.

There were clumps of lights and strings of lights for miles. So much light that the low, moving clouds were lit up by it. Illuminated caterpillars, buses, were still running, a police siren dopplered past, and there was a constant low-level hum of unseen traffic, a permanent carrier-wave of sound. My home town would have settled down to sleep by now, become silent, and in the morning would wake up. This place never tired, never slept. This was the nonstop future, the metropolis, spread everywhere so that now the rural was a subset of the urban.

And the characteristic of the metropolis is that different, incompatible ways of experiencing coexist, that may (may have to) conflict, and must all be incorporated into any synoptic simulation. So that Bruce’s position, while I might disagree with it, had to be taken into account in our modelling. It would be something I would bring up with the group. Jennie the sociologist would probably call it ‘radical deviancy from normative behaviour patterns, fascinating.’ It would be included in both our ‘culture’ and ‘politics’ subset metrics.

And I was feeling the frisson at being close to such a radical demi-monde, so much more interesting than the sad posing of my hometown’s arty beatnik hangovers.

But mainly I was thinking of Melanie, and how her eyes had held mine just that bit longer than necessary, that said, I’m interested.

Chapter3: Melanie at the fair

So that on Friday evening, after a busy, stimulating and productive week at the Planning School, as the others were piling into Peter’s van to go to York to see Jimi Hendrix, I was walking past emptied houses towards the squat that pulsed with music, flickered with light, and generally seemed about to explode.

Maximum decibels, a crush of sweaty, drunk, strangely-dressed people, I pushed my way through. Activity in every room and corridor. Pots of house paint and a mural being painted and repainted by anyone who wanted to join in, poetry extemporized over an electronic soundtrack, the cellar broken through under the other houses, in one cellar a girl dressed as Lolita with “Eat Me” printed across her tiny shorts reading from The Annotated Alice, in another an acoustic group playing rock classics, further on a rock band playing border ballads, a quiet, red-lit room where a joint was being passed sacramentally to the sound of an Indian raga, a harshly-lit operations room with charts on the walls, models on the long table, wary looks as I passed through. The familiar feeling of wanting both to leap in, and to examine from a distance, two sides of me in conflict, ending familiarly with me standing, Buridan’s ass, stuck.

‘How goes?’ asked a burly, bearded American.

‘I’m trying to make sense of it.’

‘But it doesn’t make sense.’

‘So then it’s chaos.’

‘Creative ferment. Don’t you feel the energy?’

‘It’s just flux,’ I said.

‘“Energy is Eternal Delight.”’

‘But energy without form is just sensation. What does it produce?’ pointing at the mural being painted over yet again.

‘We’re not trying to produce – there’s already too much production, too much consumption, too much stuff. We’re trying to change.’

‘Change what?’

‘Consciousness.’

‘And then what?’

‘Then we’ll do things differently. Welcome to the new world,’ walking away with a cheery wave.

‘Take me to the fair,’ Melanie, her arm in mine, quiet, intense.

‘Where have you been?’

‘Watching you. Trying to work out if you’re a wall or a tower. Or just a part of the scenery. Come on, take me to the fair.’

The fair, a big one, had arrived on the moor during the week, a transient outlaw-world with its own rules that appeared like a mushroom, lit up at night in fairy enchantment, and was as suddenly gone, leaving only scuffed grass and strange, fugitive memories, some good, some bad.

Now it was Friday-night busy, edgy, a little dangerous, generators throbbing by the caravans where guard dogs were chained in the dark, electric wires snaking across worn grass, smells of onions and candy floss, scratched, over-amplified pop records (someone would remember forever the record that was playing when something happened here, good or bad), the different shape of each attraction – the pendulum boats swinging out and up into the dark, back down into the light, the whirling, shunting dodgems, the graceful rise and fall of the carousel horses and their elegant circulation, the slow big wheel. All the attractions and booths brightly painted and lit by dozens of light bulbs, screaming girls opening like pastel flowers, dark, watchful men. A man’s voice: ‘Hi, Mel – you comin’ with us this time?’ She flinched, then collected herself, flared at the hard look from the swarthy man on the waltzer, who turned away abruptly and gave a vicious spin to a car of squealing girls, had laughing conversations with a couple of the women on the “prize every time” stalls.

‘I ran away with this fair when I was fifteen,’ she said conversationally. ‘I felt so boxed in at home, my sweet, muffled father, my snobbish mother, unable to pass any exams, so they sent me to a crappy school that turned idiot girls into docile wives. I worked on all the booths. I ended up in Ireland. There’s a racehorse named after me somewhere,’ she smiled, as if remembering a brief, happy time. ‘I loved her. Till they broke her. Then I had to leave. Eventually they brought me back, and prodded, poked, humiliated and drugged me. I seethed for a couple of years and walked out on my eighteenth birthday.

‘Heaven knows how I got into art college – I could hardly read or write. They like to let in the occasional unqualified oddball, makes them feel liberal. But I learnt everything with the fair. It was a world different enough for me to be able to start afresh, learn deliberately, experience consciously. There was so much I didn’t understand. And then suddenly I realized: I don’t want to understand; I want to get inside, so I’m experiencing the inexplicable, actuality; then I can draw, paint the effect actuality has on me. You see, I’m not concerned with actuality itself, that’s just stuff happening, but with making. But then again, at the end of his life, after all that making, Mondrian said, “I don’t want pictures. I want to find things out.” Then he messed up his final masterpiece. And they have to live with the masterpiece messed up. Maybe I’ll get there someday. Can I stay with you tonight?’

At the top of the two donkey-stoned steps, at the threshold, as I opened the door she peered in, wary as a cat, exclaimed, ‘it’s a house!’ sniffed, listened, ‘It’s wonderful,’ she whispered, ‘and terrifying.’ And stepped across.

That first night, her long, smooth nakedness, abandoned, remote, needy, giving, softly voluptuous, flexing like steel, slipping from nature to nature in the dark, antelope, snake, tiger. At last she lay asleep in my arms, while I, spent, my brain a boat plunging through rapids, guarded her.

When I got back from the shop with breakfast, she was sitting cross-legged on the carpet, naked in my big jumper, surrounded by books she’d pulled from the shelves, opened, tears in her eyes, ‘but is all this true? If only I knew – do you know?’ Well, it all depends on what you mean by …

After a breakfast she’d eaten ravenously, with relish, she belched, ‘pardon!’ lit a cigarette, drew hard on it, blew out a cloud of smoke, said, ‘you’ll have to phone the pub, say I’m not coming in to work.’ ‘What do I say?’ ‘Say – I’ve sprained my wrist, they’ll like that. And tell them you’re my brother,’ she added, then burrowed down and pulled pants and a toothbrush from her bear-like fur bag. ‘I made it out of her fur coat – she went ballistic when she found it gone,’ and smiled. At the door she turned, eyes fixing me, ‘don’t let them get their hands on me again.’ Not a plea, an instruction. Phoning from the box at the end of the street, I relieved the guilt I felt at lying by sounding unconvincing.

The second night, watching her sleep, the ridge of her hip and the breathtaking rush down to her waist and then up, as she twitched, her eyes flickering under her eyelids, lived lives, called out, was soothed by my touch, I suddenly realized – ‘I’m trying to work out if you’re a wall or a tower. Or just a part of the scenery.’ – that this was different. That for all my romanticizing, cycling past lit bedrooms, placing girls in dreams, my relationships had in fact been deals, transactions that resulted in exchanges of what each had for what the other wanted, the process energized by attention. That so far my “love” was what Byron said of Keats’s poems, a frigging of the imagination. That this was different, like encountering a strange creature in a dark cave. Later, too late, I realized that she had thrown herself out of a window at me and I’d had to decide whether to drop what I was holding and catch her. Or not.

x x x

On Monday morning we went into the city centre on the bus together and separated to our work places. With a kiss. As couples do. I passed the day (fortunately a lecture- not a studio-day) in smiling recollection, feeling her in my newly-alive body, smelling her on my skin, thinking through the weekend’s events, imagining the future. Hendrix had been very loud, Paul told me, pretty way out. I would introduce her to my friends, and I’d mix with hers; my world would give her security, hers would give me excitement. I was still thinking in terms of deals, transactions.

It was soon clear how incompatible were those worlds.

At first my group were intrigued, treating her as an exotic, with exaggerated care, as if she was African, or crippled. But they were soon uncomfortable, and then quickly antagonistic. She didn’t share their (our) cultural references – she could talk about putting up a big wheel in a storm, but had never heard of Antonioni. And while her knowledge was charming, local colour, theirs (ours) was the common ground, the bricks that made, the mortar that held together our shared world, that reassured us of its stability and strength. In the group each had quickly found their place; she didn’t, refused to, fit. When, around the table there erupted one of those ding-dong arguments about politics or the arts, in which voices were raised and insults traded, she was horrified to see that it was so much play-acting. ‘But how can they say what they don’t mean?’ But when she expressed her opinions (the sort Bruce had expressed, but less coherently), they at first patronized, and then, when they felt threatened, attacked her venomously, using every debating technique, fair and unfair they (we) had honed at school and university to destroy the opposition and keep us safe. I was beginning to see that the rational, enlightened, intellectual realm of knowledge and ideas, that I had been educated to believe was broad-minded and inclusive, was in fact intolerant and bigoted. And that the middle class I’d moved into, for all its liberal sentiments, was as narrow-minded and exclusive as the working class I’d moved out of. What I’d thought of, the realm of my education, as an open landscape illuminated by reason, about which our knowledge was becoming ever greater, ever clearer, I saw now as walled cities linked by lit roads through a dark jungle of the resisted and rejected. (I read this later, on the night of the Ball: “Improvement makes straight roads. But the crooked roads without improvement are the roads of genius.”) And I was becoming more intrigued by what might be in that ignored world. I noticed when it came even to attitudes to dress, how carefully the limits of individuality were policed, how strong the coercion to conform. I was beginning to doubt.

And how Melanie hated our endless talking, our second-hand knowledge, our simulation models, our game theory. ‘“Simulation?” “Model?” This isn’t a game – this is the real bloody world you’re messing with!’ Our ‘monstrous panopticons!’

I did no better in her world.

Although I did little drawing or painting after ‘O’ level at the art college, committing ever more of myself to the linear, the logical, the verbal, I continued to read art books and go to exhibitions, and I prided myself on being open-minded and knowledgable. But with Melanie and her fellow students, I realized that what I knew wasn’t art but art history. Faced with something described as a “work of art”, if I couldn’t place it in an established context, I didn’t know what to think or feel, and could only fall back on a low level aesthetic taste judgement. I was used to locating works of art in given pigeon-holes, within periods and styles, in a sequential flow in which each ‘-ism’ developed out of, or in reaction to, a previous ‘-ism’, artists were successive beads on temporal strings, art was a retrospective pattern, making reassuring sense. Whereas for them, art was what they did. Which was the bringing into being of what hadn’t existed, not as an element added to a tradition, but as something new. Existing art, the art of the past, wasn’t a tradition to be added to, but a resource to be pillaged. They were working forever on the edge of the unexisting, the abyss, stepping forward into it, in the expectation (or hope) that something solid would come into being as the foot landed. And with the knowledge that, however hard they tried, however much they believed in what they were doing, art is a long-odds gamble in which the vast majority are simply the manure that the few flowers will grow out of.

After a first interest in my knowledgable talk, they soon wearied of my analyzing, classifying, defining verbosity, my attempts to capture essences, existences in nets of words. So when I went to see Melanie in the studio they treated me with sarcastic politeness, agreed with everything I said, hummed “Ballad of A Thin Man”, asked how life was in the old folks home in the college, turned up Radio Caroline and sang along when particularly banal records were played, read Beano out loud, setting the Bash Street Kids on Lord Snooty.

Wherever had Melanie heard of the panopticon?

Despite the difficulties, I found myself ever keener to understand their world, less wedded to mine. Because of Melanie, of course. But also for myself.

At my grammar school, art was treated either as genius (something you were born with), or trade (a set of learnt skills, like carpentry). Neither of which were recognized as relevant to the school’s realm of accumulated knowledge and applied intelligence. Art was what those not up to Latin did. I was too clever for that.

And yet, in art classes, and with Penny, it hadn’t felt like that; I’d had a sense of a world (in the dark jungle?) that I would have liked to have entered. What if I had carried on drawing, painting? But I’d trusted their judgement, I was obedient. Too weak to defy them, too flattered to want to. And I took to applying myself, with the fanaticism of the doubter, through the sixth form and at university, to building edifices of knowledge and networks of theory, replacing art with art history. What might have been, the artist in me, shrivelled to a memory.

I turned to the bearded American who’d spoken to me at the party, Sam, a visiting professor at the art school. He was from a university in San Francisco, tenured there, but his involvement with Kesey, the Merry Pranksters, drugs, direct action, had made a couple of years away a sensible career move, especially after Reagan was elected governor.

Touched by my earnestness, and I’m sure thinking of Melanie, he would let me visit him in his tiny, book-filled cubicle.

‘If I want to understand what’s going on here,’ I said, my arm encompassing the art school, ‘what’s your first advice?’

‘Read Blake.’

‘And your second advice?’

‘Read Blake again.’

One evening in the pub, after the others had left on some escapade, he talked to me about Greece.

It was then that I began writing the second set of notes that are on the table in front of me, as the train slurs into yet another station, written quickly, much altered, questioning, at times desperate. It was a Greece I’d known nothing about. He said:

‘It would be easy for me to quote that irritating song that’s around, about knowing all the words, and singing the notes, but you never quite learnt the song …’

‘“she sang,”’ I finished.

‘That’s the one. I could say that you just don’t get it, as if it’s down to your obtuseness. But in fact you know such a lot of the wrong things, and so little of the right. There are whole realms of ideas and knowledge that are outside your curriculum. But you’ll need to explore them to get your head round this place. All I can do now is give you a Cook’s tour and hope you can begin to fill in the rest. Otherwise …

‘Begin with Nietzsche – he and Rimbaud are where the modern world begins, after all. The Birth of Tragedy, and his brilliant intuition of the very different tendencies represented by Dionysos and Apollo. Dionysos, the god of darkness – “for Dionysos is the same as Hades”, Heraclitus tells us. Remember that when you’re reading Blake. And god of drunkenness, dancing, ecstasy, abandon, self-forgetting. Apollo, the god of light, sculpture, dream, form, measured restraint, individuality. These gods typifying two conflicting tendencies in fifth century Athens, and in the Greek psyche. And, I’d contend, in all psyches. Resolved, at least for the duration of the theatre performance, in Tragedy – but that’s for another day.

‘The dionysian, Nietzsche tells us, breaks through, surfaces in the chaos and cruelty of war. And now, with the Vietnam war in all our living rooms, we have a new dionysian ascendancy of rhythmic and immersive music, of happenings, drugs that emancipate rather than enslave, an expanded and shared consciousness replacing the isolated ego. With Kesey, the Pranksters, the acid tests, we were so close to breaking through … It’s about being on the bus.’ An almost dreamy falling away of his voice as he remembered, then a renewed focus:

‘And of course a literal move from Apollo to Dionysos, with art students abandoning the making of static objects, instead creating environments, incorporating movement and time, forming bands, actually making music! Apollonian dream yields to dionysian ecstasy, form to flow. The artist is no longer a craftsman of objects, he’s an explorer of possibilities, an agent of change.

‘But – and this is crucial – it can’t be just a change in art; there must be a change in society. This rigid husk of a society is a prison, Hamlet’s Denmark; to work within it is to be decorators of the walls of the prison, entertainers of the prisoners, part of the prison system. Blake says, “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite. For man has closed himself up, till now he sees all things through chinks of his cavern.” We are cabined, cribbed, confined, bound in. We must break down the walls, be liberated.’

‘But surely,’ I protested, ‘to experience the infinite would be to lose oneself in the incomprehensible. We’d be destroyed like Semele. We need concepts to filter experience.’

‘Filter experience? That’s what they tell you. Does the child filter experience? Isn’t its life infinitely richer? Filter experience? Are you saying we need protecting from reality? That we’ve evolved to be unable to cope with reality? As Thoreau says, we don’t wear clothes because we’re cold; we’re cold because we wear clothes.

‘But note, Blake doesn’t say open the doors onto the infinite, which is what happened with Semele. Cleanse our perceptions and break down societal walls.’ He paused, took a drink, then resumed, getting going, on a roll:

‘You, you’re bright. But the only question in your sort of life is whether you’re an alpha or a beta. Or maybe,’ warming to his theme, ‘you rather fancy yourself as the Savage? But really, what you thought was an “education in thinking for yourself” was a conditioning just as powerful as in Brave New World. You’ve been trained to fill a particular role in a given society. Through school and university you were flattered and cajoled into being a concept-monger, by the concept-mongers, because this society needs and values concept-mongers. Beginning with Plato and his chained figures in the cave. Because the real world of democratic Athens frightened him, and because, too much the poet himself, he wanted to take the poetry out of experience, he came up with his weird idea of Forms, which has been developed and refined ever since. So that science, the intellect – especially since the seventeenth century – have placed a grid of concepts between us and reality, abstracted reality away from us, so we deal not with reality but with concepts of reality, we live at second hand.

‘And, having accepted that second-hand image of the world as the world, as reality, the lived world has become, and is becoming ever more, a representation, a simulation, what Debord calls le spectacle.

‘In the consumer society we’re cut off, alienated, from nature, from others, from ourselves. We’ve become “players” in a “game”, the game of society. And it’s a society that’s as artificial as that depicted by Watteau or Boucher. But because it now incorporates not just an elite, but the whole of society, it seems “normal”.

‘It’s too late for a Marxist revolution of production – although Marx’s precept that we must break up the old society before the new can emerge holds good – because we’re now in a society of consumption. And there’ll be no proletarian revolution, because all classes have now been incorporated into the culture of consumption, of the spectacle.

‘Politics is at best a process for choosing who defines and controls the small element of the spectacle that’s controllable, but mainly just an illusion of involvement.

‘Through personal derangement of the senses (back to Rimbaud), and direct, shocking, societal action, we can, for a moment, tear a gap in the fabric of the spectacle. It may reseal almost instantly, but in that moment there is the possibility, for ourselves, for others, of true insight, true seeing.’

He took a long drink of beer, wiped his moustache, looked round the bar at the fag-end of a dying world, the almost-empty pub in the middle of a waste land, hunched, diminished figures, as if pondering the contrast between what he was seeing and what he was saying, resolved, turned back to me:

‘D’you see how different your way is to theirs? And remember that they are as they are because of faulty conditioning – and thank heavens for that; but it’s tough for them. You piss them off because you’re an agent of what they’re fighting, you’re the enemy. On top of that, you act like a tourist. Are you a tourist? I don’t know. There must be something, or I wouldn’t be talking to you.

‘And Melanie – Melanie’s been outside before, on the run. Now she’s stepping out again. That’s tough. You’re her last link with the inside. But there’s no point in you trying to keep her inside; you need to help her be outside. I don’t know whether she needs it, if you’re up to it, or even how you do it. Without going outside yourself. We’ll see.

‘And there’s one, other, big difference between your position and ours. Back to Nietzsche: a culture, he says, can focus on the moral, or the aesthetic. The moral is the general well-being; the aesthetic is the good of the highest individuals. You and your gang of “social meliorists” focus on the moral. (Mainly because you’re not up to being the “highest individuals”; but you have been granted power and status within the social system, as part of the boss-class in the “general well-being”. It’s in your interest.) We’re for the aesthetic. Society, including most of us, is compost for beautiful flowers. Illumination comes from the brightest lights.’

He looked at me steadily, the unyielding look of a believer. He drained his glass, stood up,

:‘On the bus, with Kesey, our book was Journey to the East. There’s a line: “We had brought the magic wave with us; it cleansed everything.” We’re riding the magic wave. Either get on it, or get out of the way.’

As I walked home, with the rich welter of what Sam had said churning inside me, so much of it new, exciting, dangerous, there came, like a buoy bobbing on a turbulent sea, this thought: what if those feelings I’d had as a child, of not fitting in, of not belonging; what if that time aged twelve when I saw clearly – why didn’t others see it? – the disjunction between what life was and how people lived; what if, in Provence, when I suddenly saw, and afterwards the burrowing doubt that led me to write out, pin on my wall, “one knows all the time one’s life isn’t really right, at the source”; what if all these, rather than being the morbid symptoms of maladjustment (that I’d worked so hard to compensate for, cover up), were in fact signals from the dionysian within myself? What if I’d come upon one of those doors in the wall that if you don’t enter now, you never find again, and forever remember with poignant regret?

And yet, as I opened the door on my piles of books and careful notes and designs, I had a flood of warm feeling for what we were doing in our studio, a renewed optimism that we were applying intelligence to making a better world, within the rules, in this world, and that this was significant, and real …

Chapter 4: William Blake and the Arts Ball

On the day of the Arts Ball I read The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

It is impossible to convey the effect of reading that firework-box of statement and contradiction, directness and ambiguity, celebration and subversion, all carried along on a juggernaut of certainty. Line after incandescent line of it could be the object of profitable thought, of meditation. The line I should have focussed on was, “If the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise.” Instead, having read it, my old thoughts being, like Swedenborg’s writings, “the linen clothes folded up,” I declared: ‘Now – I understand!’

For was I not trying to ride, a foot on each, the tyger of wrath and the horse of instruction? And wasn’t Melanie, surely, “Energy” and I “Reason”; and as Reason is “the bound or outward circumference of Energy”, clearly I was there both to circumscribe and protect her, a tower and a wall!

It was all so clear in my head: we would come together at the Ball, and there would come that Perfect Moment; I would give her the expensive necklace I had bought for her, with the card on which I had written “You are Eternal Delight”, and she would understand, and we, the King and Queen of the Ball, would walk together into the future. The Start-rite kids.

As Melanie was one of the organizers, I was to meet her inside:

‘But where will I meet you?’

‘Find me. That’s what it’s about. Finding someone. Maybe even yourself.’

Crazily-dressed, excited figures were converging on the Art School. I had tipped my hat to craziness by painting my plimsolls as feet, hommage à Magritte.

The school had been transformed, with lights flashing in the windows and painted constructions altering its appearance, making it skewed, expressionistic, ambiguous.

I entered under the banner:

“Hellzapoppin! The World Turned Up Side Down.”

Through a painted arch:

“Prankster Theatre – Do You Believe In Magic?”

Into an unlit corridor, painted black:

“The Road of Excess – Pay Before You Start.”

I entered, quoting back: “once meek, and in a perilous path, the just man kept his course along the vale of death,” sure of myself. Briefly.

For the floor of the dark corridor was uneven, sprung, covered in foam rubber, and soon I was pitching about in the dark, with squealing figures around me, I was bruised against hard objects, absorbed into softness, disorientated by thudding music, aware of flitting figures: a sweet smell and soft flesh and a whispered, ‘“the nakedness of woman is the work of god,”’ aroused I reached, touched, she was gone with a derisive laugh; an insinuating voice by my ear, ‘“better murder an infant in the cradle than nurse unacted desires.”’ Then an imp in front of me yelled, ‘“purge your mind of all hope! Leap onto joy like a wild animal and throttle it!”’ and pushed me and sent me sprawling; I protested, ‘I say …!’ and my voice was echoed back amplified, ‘I say! I say! I say!’ a mocking policeman.

I staggered through at last, shaken, embarrassed, angry, ready to complain to somebody, and out into the main hall, under yet another banner:

“The Palace of Wisdom

Energy is Evil! Evil is Hell!

Welcome to Hell!”

Before I could catch my breath and look around, I was whirled onto the dance floor by Steffie, wearing green body paint, wisps of gauze, and little else, who squealed ‘Richard! Dance with me!’ and draped herself over me, softly sweating, desirable, does she really fancy me? I felt myself yielding, oh unfelt form, ‘But I have to find Melanie,’ I whispered in her delectable ear. She sprang away from me, hissing, ‘don’t find – be found,’ closed up and drooped like a flower at night. ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t …’ I began, and she ran away, laughing mockingly. I felt a flare of anger, then a hand on my shoulder. It was Bruce, in ringmaster’s outfit, complete with moustache, top hat and whip.

He led me to a small table, took out two small bottles labelled “Drink Me”, lit a fat joint labelled “Smoke Me”, pulled deeply on it, pronounced: