Rural Languedoc. The South of France. Summer 1976.

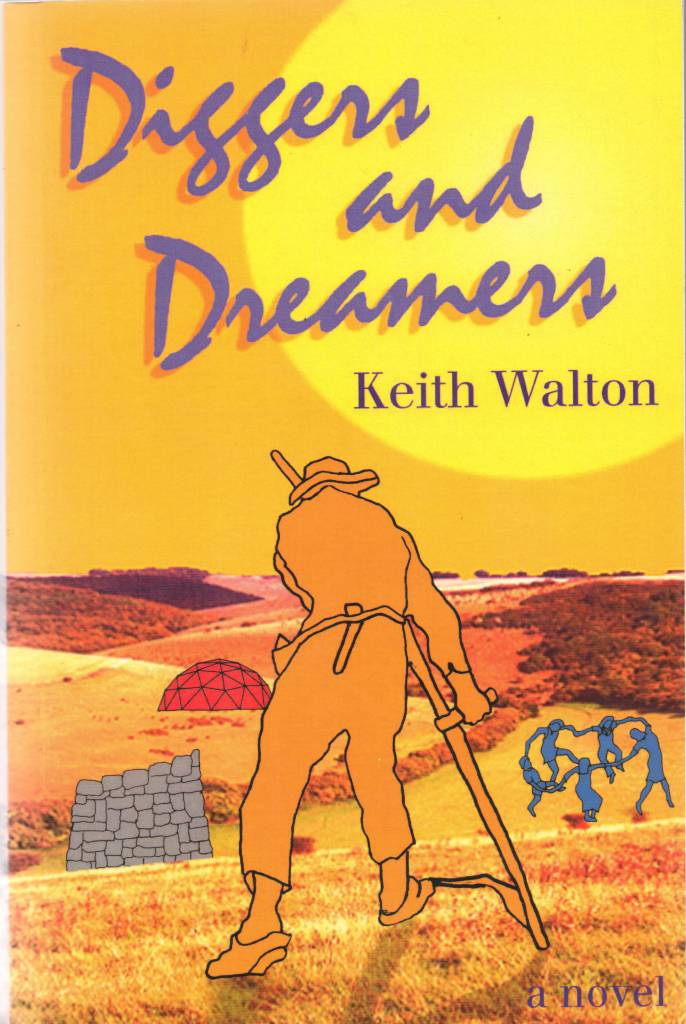

“There is another world, but it is in this one” – and the characters in this novel, in their different ways, mean to find it.

Kris and Jane are an idealistic young couple who have bought La Balme, a run-down smallholding near Albi, city of the Cathars. But Jane has had enough and gone back to London to earn money to pay for repairs, leaving Kris to pursue their dreams alone.

Through the sweltering summer, as the drought intensifies, Kris learns traditional skills from his paysan neighbour, Gaston, builds a mysterious tower (he doesn’t know why), and begins to revive La Balme. Through work, and meeting the motley incomers: enigmatic Sylvie, Fred the revolutionary, Edvard and his magical domain, self-sufficient André, Kris feels he is beginning to find himself and his place.

When he meets and has an affair with Gabrielle, a young Parisienne full of the spirit of May ’68, he discovers with her the purpose of his tower, and glimpses a new world coming into being. But with the return of a transformed and resolute Jane, he must face the question – which future world does he really want?

With its rich cast of characters, and exact descriptions of rural living, Diggers and Dreamers is both a timeless story of city-dwellers starting up in the country, and a time capsule from an era when it still seemed possible to “treat your desires as realities” and set about creating a new world.

358 pages £5 Available from brimstone-press.com

Some definitions

The Diggers were radical dissenters in mid-seventeenth-century England who cultivated abandoned land and advocated social and political reform.

The name and philosophy were adopted by activists in the late 1960s.

To dig: ‘to understand, appreciate, experience (informal, dated)’. OED.

Dreamers: ‘unpractical persons; idealists’. OED.

This is the full text of the novel. 100,000 words.

CONTENTS

(page numbers are from the print edition.)

PART I: RETURN TO THE HILLS

1 Albi 3

2 The river 9

3 Sylvie 16

4 Into the hills 22

5 Approaching the feu 30

6 Le feu St Jean 37

7 Midsummer dawn 46

8 A new day 54

PART II: BUILDING THE TOWER

1 The idea 63

2 Laying the foundations 68

3 Building the wall 80

4 A ‘Symposium’ 82

5 Fred visits 102

6 The letter 108

PART III: A DETOUR

1 A bubble of light suspended in space 113

2 The walking manikin 118

3 Maire-Claire visits and brings news 122

4 Surviving 126

5 A Dutch interior 131

6 The second letter 148

PART IV: THE WORK RESUMED

1 Pages from Kris’s diary: mowing 155

2 Pages from Kris’s diary: the neighbours’ farm 165

3 Pages from Kris’s diary: ‘each human being lives

beneath his own dome of heaven’ 177

PART V: KRIS FIXES THE ROOF WITH RICHARD

1 Stepping into space 195

2 A night out 207

3 Night life 216

4 Richard leaving 225

5 Return to Albi 232

PART VI: STEPPING OUT

1 Driving south … 239

2 Gabrielle 251

3 Mushrooming 257

4 Gabrielle visits: ‘La fossiure a la gent amant’ 264

PART VII: SUMMER’S END

1 The first days of autumn 281

2 Picking apples 285

3 Vendange 292

4 Talking to Jane 296

PART VIII: JANE RETURNS

1 “Europe 2000: a tale of the future” 303

2 Jane arrives 306

3 A fight with Jane 312

4 They walk 318

5 To St Affrique 321

6 In St Affrique 327

7 Jane leaves 330

PART IX: LEAVING

1 Last pages of Kris’s diary: pig killing 335

2 Kris leaves La Balme 353

Notes 356

PART 1: RETURN TO THE HILLS

Chapter 1: Albi

I watch the cream and red train disappear slowly round the long bend. The last I see of Jane is her hand sticking out of the window, her fingers spread out like the ribs of a broken fan. I stare along the empty line until the noise of the train dies away and the rails no longer rumble and the humming wires fall silent, and then for some time after. I turn and walk through the dark station and out onto the dazzling dust area in front. It is midday and very hot and the white dust is endless. I stop, shadowless and blind, aware suddenly of the space all around me, aware that I do not have to do what I intended to do when she left, the thing I promised myself I would do for her, so that she can return, the one big thing. I stare up at the enormous sun. Then I walk quickly to the car and, instead of getting in and driving back up into the hills, I take out my bag and walk towards the centre of town.

We walked up this road eighteen months ago, rucksacks on our backs (Jane’s was new and she wore it awkwardly), hand in hand, distant. We had left our trunks at the station.

As we passed this little house, I exclaimed ‘Yvonne de Galais’ house, that le grand Meaulnes used to stand outside!’ and turned to her, laughing. She smiled a thin smile.

We stayed, that first night, at this hotel, an old place superficially modernised with plate glass door and formica desk. We sat on the bed, beneath the aged flowered wallpaper and the picture of Jesus, staring across the red roofs to the hills, green, grey and white. I was excited, saying I hoped we’d find a place soon so we could start preparing the ground to be ready for spring:

‘Shallots can go in in February, you know. And there’s still time to sow broad beans. If you start behind, you never catch up. Imagine – our own place, growing our own food. Two acres and a cow, Cobbett says that’s all you need – and that’s to feed a family! Of course we’ll have goats instead. They eat anything. And you can freeze goats’ milk, but not cows’ – something to do with the cream.’

And on and on. Jane sat in silence. Then she got up quickly, went into the bathroom and was sick. Maybe we should have turned round and gone back then. But we’d emigrated, given away everything we couldn’t carry, were making a fresh start. And for me there was more to it than that.

The next day we caught the bus up into the hills, to buy a place, to live, to be free. Within two months we had moved into our own house, with our own land, our own vines. And I had planted the shallots, late.

‘You do still love me, don’t you?’ Her last words as the train began to move, her eyes searching my face. Or maybe memorising.

‘Of course I do. Close the door.’

At the building site a crane turns slowly across the sky. An orange crane, a blue sky, the orange and blue complementary colours, of the same intensity, shapes that vibrate against each other; when I screw up my eyes I can’t tell which is in front of which – I can fancy the shape of the crane to be an absence of blue, a cut-out revealing the orange beyond as it turns slowly, a moving absence. But what, then, is the orange? How strange to be alone! To stop spontaneously, to follow my nose, not having to explain or make sense of things, with Jane not here.

The train will be crossing the plain of Gaillac; she will be looking out over endless rows of soft green vines, where the woad once grew that built the towers of Toulouse, long ago. Pastel.

And now I reach the anchor, the huge anchor set on a plinth, eighty miles from the sea. I sniff it to see if I can smell the sea. It smells of iron and heat. How fierce the sun is! I cross the park and plunge into the public baths.

***

I stand in the white-tiled cubicle and let the hot water beat on me until I am almost senseless. Endless hot running water – imagine what it is like to someone who draws his water from a well and heats it in a black polythene bag in the sun.

I remember reading of South American women moved from squatters’ shacks into apartments, showering a dozen times a day, astonished at this miracle, not knowing where it came from, not realising that, unlike a miracle, they would have to pay for it with more than faith.

At last I come to, and wash myself voluptuously, moving into and out of the hot cascade. I examine my hands, enlarged and roughened by hard work, no longer the hands of a student, an academic, a bureaucrat. I look at the scabs – each the fading record of an incident; at the scars – intensifying with time, as if growing confident of their permanence, fixing events. I feel my broadened shoulders and my thickened arms, the product of two years of carpentry, eighteen months on the land. At thirty I have grown into myself, filled the shape I was meant to be, ready at last to take my place with the other men of my family.

But now I have become hard and stiff. So much for the healthy outdoor life. Thoreau writes that the farmer, that image of the healthy man, is not healthy, because he has lost his elasticity; he has become an overworked buffalo, stiff leather in stiff leather. And Jane and I have become ox-like, starving our imaginations, blinkering our visions to the narrow world of our house and land. She is right to go back to London; not just to earn the money we need, but for her own sake. And I am right to stay: for I must remain within this small compass until there is a resolution. And Thoreau’s prescription for the farmer? “It would do him good to be thoroughly shampooed to make him supple”. I apply the soap thickly to the sponge and rub myself all over. As I wash my soft, white places, I remember the softness of her body, our nakedness together, even in that last, fear-filled grappling. We have never been apart. As the water pours onto my head, drips like tears from my eyelashes, I realise the seriousness of what we have done; that what seemed a few hours ago sensible and rational, is a leap off the edge. We have acted as if we believe in fate. I wonder if we do. I grip the sponge and whisper her name.

I wash my hair, shave, clean my teeth, dry myself, put on white cotton trousers, a white collarless shirt, sandals. And – as I comb my long hair in the misted, rubbed-clean mirror – Thoreau’s definition of health? “One sensible to the finest influence; he who is affected by more or less electricity in the air”. Ah.

I stuff my dirty clothes into my bag, step out of the steamy cubicle into the cool, echoey building, and go out into the full heat of the sun.

***

Nothing moves. I can feel the surface of my damp hair crisping in the heat. The town sleeps, coshed by the sun; or spellbound. In front of me the war memorial, a triumphal red brick arch tattooed all over with the hundreds of names of the dead, set in rectangles of sharp white gravel and beds of vermilion flowers, bounded by low dark box hedges exactly clipped, a double row of black cypresses leading to and from it. The wide square, Di Chirico shadowed, empty. Nothing moves.

Except behind the buttressed walls of the vast red cathedral that rises hallucinatingly above and shadows the town. Within, the level of blood rising slowly, gurgling – spouts suddenly from gargoyles, bursts out through windows, pours down the walls darkening with crimson the scarlet brick, floods the narrow streets that now echo with screams and the crackle of fire, bursts in a foaming wave from the narrow streets, surges across the square, laps around the bases of the still black cypresses. I hold my breath as the roots eagerly suck in the blood. The tops of the cypresses, at first still, begin to vibrate, shiver – then burst open, flower, with a soft white oozing that shapes, re-shapes then fixes into the forms of heads. There is a head on the top of each of these black cypresses, and each the head of a hero. My heroes, the heroes of my life: long-haired and shaven-headed; bearded and fresh-faced; composed and falling apart; gazing ecstatically still and chattering matily; singing; yelling angry obscenities; mouthing endless concentrated monologues – altogether a welter and babble of noise and movement that somehow makes sense, that is – my world. I gaze enraptured.

And then the tall orange crane turns slowly through the blue sky; the hook descends and lifts the great anchor high into the sky, turns again and the anchor rattles down and, with its arrowed barb, hooks under the arch and lifts. The arch, on its circular pedestal, rises, brick foundations falling, revealing a black emptiness; and down it swirls the blood, with maelstrom twist, gurgles, and is gone. The heads are silenced and stilled, turned to stone… begin to topple… smash to white gravel. The cypresses shiver and then are still. I close my eyes. “Oxidise the water-spouts”, I murmur; “stuff boudoirs with the fiery powder of rubies”. Such things I see, inside my head!

Out there, a creaking sound. I open my eyes. Everything – arch, anchor, crane – is in its given, habitual place. A cyclist in a big cap is cranking slowly across the square. A grey shutter squeaks open and a man in a blue vest looks blearily out, scratches himself, yawning. The first car, a Dauphine, patched and particoloured like a circus car, appears in the street. The pendulum resumes and the clock ticks on.

Was it vision? Memory? Premonition? Or imagination, simply, long buried, emerging ….

Smartly dressed figures appear and walk purposefully with briefcases.

The streets fill with cars and motor cycles and the air grows blue with petrol fumes. Slim, trim shop assistants in white blouses wind open window shutters. A clock strikes twice. And then another, deeper. I run my fingers through my dried hair. Jane will be in Toulouse, waiting for the Paris train. I go to the car, stow my bag and walk into town, a tourist.

Chapter 2: The River

I go straight to the record shop and stare through the window at the record.

‘How can you even think of buying a record, Kris,’ Jane had said when I pointed it out to her; ‘that’s a month’s petrol.’ It was released the month we arrived.

‘But I always buy his records.’

‘You always used to. Past tense. Those days are over. This is the real world.’

‘But he’s the real world.’

‘Grow up.’

I’ve waited eighteen months. I walk in, buy it, hold it, tense myself for the accusing voice. It doesn’t come. She isn’t here. I am here on my own. This afternoon I am living as if I am free.

I look around. The shop has changed a lot since I first came in ten years ago. The proprio is the same, but his once wild hair and shaggy beard are now trimmed to a perfumed neatness, his granny glasses replaced by executive gold rims, the saggy rainbow sweater discarded for a tight Fair Isle slipover, his whirling energy constrained to a nervous fastidiousness. The white paint, the gaudy posters, the scrawled messages are gone; now there is olive hessian and classical record sleeves on the walls. Albinoni plays; then it was Leo Ferré. And I was a boy with short hair and cycling shoes nervously buying a record I had heard playing in the youth hostel. “Le Temps de Vivre”, by Georges Moustaki. I leave, clutching Blood on the Tracks.

* * *

I pass the smart shops. The patisserie, its cakes so carefully made, so highly finished – enormous red strawberries glowing through a magnifying glaze – that they resemble works of art more than food. The charcuterie, where thick sauces and gelatin moulds disguise animal and vegetable origins. The parfumerie, with its exotic and alluring scents, unhuman smells to swathe, disguise, transmute the human body. The magasin de mode’s window of gorgeous fabrics draped upon impossible figures. Bourgeois France, in which everything, it seems, passes through a stage of artificiality (conscious mind? cultural sensibility?) before it is consumed.

How that intrigued me! I was ambling along, a boy, eating a pêche – a cake shaped like a perfect bum; I was sinking my teeth into the soft pink cheeks – all those years ago, when an attractive woman came out of this shop, clutching a large dress bag, her eyes bright with pleasure at her purchase (I imagined her trying it on), smiled absently at me as she passed, her perfume wrapping round me. Without thinking I turned and followed her. She wore no stockings, had slim brown legs, walked quickly in high-heeled sling-back shoes. Beautiful brown hair with blonde highlights, smooth suntanned skin. She was slim and sleek and wonderfully middle-aged. I followed her without her knowing.

She reached her car, a white Citroën DS (déesse, yes), and, as she opened the door looked up and saw me watching her, half hidden. A frown passed across her face, followed by a smile – not directed at me but up, at the sky. Then she looked very directly at me. I was paralysed. Not frozen – no Medusa, she – but as paralysed as if she had opened her blouse and stood bare breasted in front of me. Then she turned and got into the car and turned the key. And it wouldn’t start. She tried again. And again. I had an age in which to do something, if there was anything to do. I just watched. At last the engine roared into life and she drove away, her hand through the window giving a flutter of a wave, and then she was gone. I started after her helplessly, then turned, feeling strangely empty, and resumed my life.

Often I would remember, and imagine alternative possibilities, each of them forking ever further from my existing life into an entirely different present.

Such are my memories of bourgeois France. Now I live in peasant France. And I need to remember why.

* * *

An untidy bulk backs out of the bookshop, blocks my path, steps back into me, whirls round crying:

‘Boun Diou!’ Pieter often slips into patois when surprised; I still don’t know whether from a genuine empathy with his peasant neighbours, or something wished for. Surprise is replaced by delight as he pumps my hand:

‘Kris! How are you?’ The rolled ‘r’ and the short ‘yu’ distinctively South African.

‘Not bad. And you?’

‘Good, good.’ He taps the fat book he is holding, La Terre d’Oc. ‘Fascinating. The parallels of land and belief, form and idea in a place. That bloody fortress, for example,’ he points at the cathedral, ‘every brick made with the blood of the broken Cathars. One day that blood will flow again, out of the bricks.

‘And the springs – do you know of them, the resurgences? Even the name. Pure cold springs that bubble into the bed of the Tarn. Imagine, within the muddy, thick, warm river those separate, cold, pure streams. And hard, that water, hard and clear. The perfect image of the Other Way, Our Way. And they have their effect – the river clears as it flows downstream. Does the Mississippi, or the Seine? No – but our river does. Parallels, you see.

‘But you’re alone – where’s Jane?’ I will have to get used to this question, invent the appropriate response for each questioner. He listens, his lined, tanned face grave beneath the grey hair, says:

‘Women live in the present – they see things as they are, not as they might be. And she sees that she has no home – she needs a home. But you have a vision. Now you must be strong, stronger than you have ever been. Work with all your strength. Make that vision a reality. Turn the damaged and neglected into a home, the wilderness into a garden. Then she can return.’ We shake hands and he turns, then calls over his shoulder:

‘Come and see us, soon. Hendrika likes to see you.’

‘Sure.’ And I walk on, wondering if it is what I want, any of what he said. The path leads, ineluctably, to the river.

* * *

I walk slowly down the steps, between the stones, into the noise, and stand, my sandalled feet an inch above the milky brown river. It is not so much the speed of the river I notice – though that’s impressive, as a toppled tree speeds past, a bird still and sharp on its topmost twig – as its size. A hundred yards wide, of unknown depth; what volume of water? What power. The water piles against and divides around the bridge piers. The surface is marked by swirls and ribbons of movement and small conical holes like holes in mud. And are there really springs, bubbling springs and threads of clear water? The mill remains, empty now and boarded up. The terrace where we sat at long tables under the bamboo lattice is now a desolation of rubbish.

It was a youth hostel when I came, alone, a temporary one, open for the summer, run by a group of students from Paris. They boiled cauldrons of apples and we helped ourselves. They played chess and argued and drank, and giggled over small, shared cigarettes and caressed and – I suppose – made love. There was the pretty gamine with long hair and big eyes who would pass hours motionless and then instigate a sudden collective madness. There was the serious girl with short hair who kept it all going. The patient, methodical, bespectacled man, and the man all the girls fell for and who, you insisted, wasn’t handsome but was, you conceded, attractive.

And the non-stop record player – songs of Cuba, Satie, Charley Patton, Bach, Dylan, Nina Simone, Congo drums, Brassens, Misa Luba, Monteverdi, Reggianni, Miles Davis, Milhaud, and more, and more. Most of it music I’d never heard, that I’ve only identified piece by piece in the years since, that I’ll still be identifying years hence; the music of those three days (as I rested up) exists in a place inside me, waiting to be heard again to be recalled. Eighteen months later I imagined those students taking part in les événements in Paris. As I watched the savagery of the CRS on TV I hoped they were alright. Yes, the one I fell for was the longhaired girl; and the one I thought I should like, the shorthaired.

Abroad for the first time, cycling to the Mediterranean, crossing that line, that exact line that separates North and South, into a different world. I left the world I knew and entered a different world. The elastic connecting me to home stretched (how I missed home!), and snapped. (My bike broke miles from a bike shop, was repaired by a blacksmith – a different world.) I swam in the Mediterranean. I bought red espadrilles for the girl I wrote to every day. I spent three weeks in Provence and the Midi, in Roman Midi, in the Midi of Van Gogh and Cézanne and Petrarch and the Troubadours and the Cathars and olives and vines, that reminded me of Greece although I had never been to Greece, that I would go to Greece to find; in a different culture, in ‘culture’.

I arrive in Albi, at what I think is the last stop on my sickle swing through the South, replete and, it seems, complete. I’m sitting here, at a long bench, beneath a vine-covered trellis, after a meal I’ve made myself, of rice, onions, tomatoes (those sweet, juicy, misshapen southern tomatoes) and cheese (gruyère, all melted in), followed by goats’ cheese and baguette. There is coffee in a glass by my hand, the hard sugar lump dissolving, and a glass of wine. It is evening, dark and warm, a Southern evening. The air is soft on my skin. The stars sparkle. I listen to the river’s soft flow, and watch the last light fade from the sky. I am cycling fit, full of the books I’ve been reading (La Nausée, Parôles, Thus spoke Zarathustra), the experiences I’ve had (Mont-St-Victoire, La Fontaine de Vaucluse, the girls at La Ciotat). My diary (which is now ‘a journal’) is open in front of me. I am surrounded by activity that I am not part of, conversation I do not understand. I am ready to reflect on my adventure. I am warm and full and rather pleased with myself. Click. A new record. Georges Moustaki. “Le Temps de Vivre”. I feel very, very happy. I write:

“I am surrounded by strangeness and activity, and I am at its still centre; in it but not of it. I am alone and unafraid. I am free.” And then suddenly I know what I have to do. I have to go on. The next day, instead of heading north, retracing my journey here, I cycle up into the hills, into silence, towards nothing. The adventure I thought was ending is just beginning – or rather it is beginning a new, more dangerous phase. When I returned to England I gave the girl the red espadrilles and broke off our relationship.

Such moments happen to you when you are twenty. At thirty, maybe you have to make them happen. I look down at the thick water. I imagine the steps continuing, step by step, to the bed of the river. To the spring, the resurgence.

I step down, into the water. A smell of mud and weed rises. My foot sinks through the surface, disappears, and then grounds on the invisible step. The water is cool. It separates around my ankle. I step down my other foot, deeper, the water to my calf, cold now, tugging at my leg more urgently; my sandal touches, slips, I almost fall, recover, set down my foot. Step down again. And again. Each step takes me away from the bank, into the river, down, out, the water rearing up, filling my vision, the noise of it filling my ears, blocking out everything else, pulling at me. I stand, waist deep, divided at the tan t’ien, half in water, half in air, exactly between. Now. Decide. To descend, step by step, into the cool, muddy water, into the dark, descend into the stream, the silence, the single flow, seeking the spring. Or climb back, out of the buoyant water into the light, the air, the weight, and all that bloody complication….

Turn. Return. How the water plucks at me, clings to me, pulls me down, drags me in! Step by step, heavy with water, slipping, almost panicking, I heave myself up, out of the water, up the steps and stand at last on the stones, the water draining from me, fizzing to nothing on the hot setts, the quayside solid beneath my feet, the air hot around me. I’m panting, and shaking, shocked at what I did and have almost done. I stand and wait. Patient as an animal. Until I have somewhere to go, until a destination emerges into my mind. And then I set off, not towards the car, no, but across the bridge, over the river, towards the boutique, wondering suddenly if Sylvie will be there.

Chapter 3: Sylvie

Sylvie squeals with delight, cries:

‘Kris! At last!’ as I push open the door, the sheep bell ringing, and step into the shop. She throws her arms round my neck and her body melts against me. She is small and feels soft and smells sweet and I can’t resist kissing her hair. She pulls away, eyes shining, saying:

‘I’ll be with you in two ticks,’ moves rapidly round the shop switching off spotlights, stopping the tape (Ziggy Stardust), checking windows and doors, pinching out incense sticks – their fragrance hangs in the air and a thin line of smoke rises and twists from each and then stops – pushing her tarot cards and detective novel into her overstuffed bag. I stand, mystified, as she moves quickly, energy released, a creature suddenly liberated, in and out of the sunlight, talking all the time:

‘I knew someone would come. What a day! Claudine abandoned me!! I was beginning to doubt – no, not really, but if you hadn’t … I’m glad it’s you,’ a quickly flashed smile, steady eyes for a moment. ‘I’m really excited. Oh, here’s the money, I sold two salt boxes,’ of wood, that I had made and painted. It’s more than the price of the record. ‘What’s the record? Oh, it’s brilliant. “Tangled up in blue”,’ she warbles. ‘I really sweated to sell them – remember that, won’t you?’ A West Country softness to her voice, short skirt, thin blouse knotted at her midriff, shiny skin, long hair pinned up in arabesques and folds, with just enough wisps floating free to look negligent. ‘Why’s half of you wet?’

‘It’s a long story.’

‘Don’t tell me. I’ll have something to fit you at the flat. Okay, I’m ready. Yes, Cinders, you shall go to the Ball,’ at the mirror, staring at her reflection then shaking herself free and clattering in her Minnie Mouse shoes to the door.

She locks the door and sighs, as if she is locking the door of a prison from the outside, and turns, free.

‘But…’ I say.

‘Shsh,’ she says, and looks down at me from the top step, waiting. The moment stretches, tears are at the edge of her eyes, when at last I remember:

‘May the humble Bernart de Ventadour escort the Lady Eleanor to the feu St Jean?’ Her face lights up, she courtesies:

‘The Lady is pleased,’ she says, gravely, and we walk a few steps along the street in stately formality, then she laughs and squeezes my arm and lays her head against my shoulder and whispers:

‘I need this.’

So do I.

It is Midsummer, the eve of St John’s day, traditionally a night of bonfires, a tradition abandoned by the locals, revived by Edvard and now, after three years, the main festival and gathering of the incomers. And I had forgotten.

‘Jane’s gone, then.’

‘Yes. Midday. Glad to get away from me.’

‘Not from you. From this place maybe, especially from up there, your situation, but not from you.’

‘Mm. And Jean-Jacques?’

‘Sodded off. Starts muttering about “sitting beauty in his lap” and “finding her bitter”, and needing “to return to the soil, to seek a duty, to embrace rugged reality …” Then he sodded off.’

‘Rimbaud.’

‘What?’

‘He’s quoting Rimbaud.

‘Who the hell’s Rambo?’

‘Poet. Gave up writing at 19, became a gun runner and slave trader, died at 37.’

‘Brilliant – Jean-Jacques’s forty, for Christ’s sake.’

‘Rimbaud was a great poet.’

‘Bully for him. I’m pissed off with being a muse, I really am, I really, really am!’ Her voice is low, intense, angry. I want her to let go of my arm but she clings fiercely. I’m relieved when we reach her flat.

* * *

‘How about these?’ A pair of her trousers. How gorgeous to wear them. Far too small. I have to settle for a pair of Jean-Jacques’. She goes for a shower.

I look around, wondering again at all the things she has collected, or rather, accumulated. Sixties records – no record player – American books, French magazines, brass bells from India, mandalas from Tibet, worry beads from Greece, slippers from Morocco, postcards from everywhere, badges – a waistcoat covered in them, worthy of a Peter Blake painting – teak elephants, pottery incense holders, road lamps – red petrol, yellow battery – a white seagull that bobs slowly up and down when I pull the string, clockwork tin toys from Eastern Europe – a cymbal-playing bear, an acrobat; embroidered butterflies from China, Japanese paper kites. And the only time she’d left England was to come here. The walls are yellow, the ceiling blue, the shelves and chairs and table and doors and window frames are inexpertly painted in primary colours. It looks, I suddenly realise, like the room of a child living on its own.

An attic flat in the centre of Albi in a run-down block looking out over the red roofs. Maybe we should have stayed in Albi. Maybe we went one step too far. Because Jane too loves France. The difference between us is that I love being an alien in France, she loves being at home here. As I was experiencing being comfortable with solitude for the first time, she was here for a year before university, feeling at home for the first time. We love different aspects of the same place; we love the same place for different reasons: therefore we love different places? The same thing experienced from two different angles is two different things. Is this true? It’s as if it’s true, so it might as well be.

‘Now,’ Sylvie says, ‘what shall I wear?’ Wrapped in a towel, hair wet and straggly, the shine washed from her, her face tired, she looks quite plain. Sylvie?

‘Come on!’ she commands.

‘I know nothing about clothes,’ I protest.

‘Not good enough. You don’t try. Feu St Jean. Midsummer. Fire!’ She disappears and returns in a red dress, yellow shawl, large straw hat, radiant smile. She parades, crossing and recrossing in front of the window, turning round in the light, the dress crackling around her.

‘No? No. Okay. The longest day. Fertility.’ A green dress, long and simple, with a fitted bodice. A flower headband. She is slender and willowy, she looks like Guinevere, the Guinevere who never had children, waiting.

‘Night?’ Her face dead white, her eyes cold and remote as stars, a black dress with a red slash across the heart.

‘No!’

‘Too much, eh? Come on, there is something you want me to be.’ I daren’t even think. She pulls the dress over her head and stands in bra and pants, leaning against the door jamb, inspecting her fingernails, beginning to be bored. Stray hairs are trapped by the elastic of her pants. Her belly round and smooth. She spots something and walks over and moves a magazine. Her attention caught, she begins tidying up; or, rather, moving things around. Forcing books onto overstuffed shelves, throwing shoes into corners, making heaps of clothes. She does it impatiently, as if things bore her – she often says ‘we have too many things’, surrounds herself, buries herself in them. She moves lightly, her feet flexing expressively. Her skin is smooth, and although she is suntanned, she looks pale, as if the flesh beneath her skin is white. Her long hair flows over her face when she leans forward, hiding it. She finds a book of Jean-Jacques’. She stares at it with great intensity then walks quickly to the window, drops it out, into the river, and turns back into the room, dusting her hands, smiling in triumph.

‘You should be an actress.’ I say. She laughs:

‘I am, I was. Better than you might think, my friend and I. You’ll know her, she’s famous now, gorgeous, you probably fancy her, maybe you’ve wanked over her photo. It’s the eyes, men’s eyes, they strip you till you’re either raw or hard. It’s not right. I perform my life. No spotlight till I find what I want to do.’

‘Light.’

‘Perfect.’ She kisses me, her hands on my shoulders. Her lips are soft. I feel the heat from a body that is very close but not touching. My hands hang helplessly. She is gone for a long time. She comes in very slowly. She is wearing a long dress of thin muslin. Her face is white, with gold and silver dust sparkling on her cheeks and forehead. In her hair, which hangs long and straight, there is a large gold slide that frames her face like a halo. A moon pendant hangs down between her breasts. Long dark eyelashes. Her eyes dark pools in which two spots of light glimmer like pearls in the depths. She advances slowly, gravely. She is from another world. But it is in this one. As she reaches for the yellow shawl she says, her voice husky:

‘The stuff’s over there – do you mind skinning up? I’m feeling a bit shaky.’ I reach for the Capstan tin. As I soften the resin over the match flame, I hear a song in my head. From Ziggy Stardust. As if the tape has been playing on in my head from the time Sylvie stopped it in the shop. I make a strong one. They are French papers, ungummed, and I have to tear off a narrow strip to make a fibrous edge that will stick. The tape has reached the final track. I light up and hand her the joint. She takes a long, deep drag, and holds the smoke in, eyes closed. She breathes out, sighing:

‘That’s better,’ opens her eyes, pearls become diamonds. She passes me the joint. The words I hear, the last track, running through my head, “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide”, as I inhale, she shakes her head, as I breathe out says softly, in time to the words: ‘such fools, what we do to ourselves,’ and holds me gently as I burst into tears.

Chapter 4: Into the hills

The shops are closing, the streets emptying. The sounds of television, of voices low in conversation or raised in anger, of the scrape and tap of knives and forks on plates, come from behind half-closed shutters, worlds closing in on themselves.

We drive out of town through streets abandoned to dogs, through sunlight and shadow as sharp as knives. Past the cemetery, with its blank walls and black cypresses. Past the out-of-town hypermarket, looking gaudy and temporary in the middle of acres of empty tarmacadam. Across a no man’s land of unmade roads leading nowhere, small factories built of grey concrete blocks and asbestos, plots of weed-infested land marked off by single wires, of part-built houses with raw concrete steps leading up to metal-rusting concrete rafts, of shacks in patches of bare, overused land with chickens scratching patiently in the dust. A zone of transition, for those on the way up, or the way down. Something American about it. A zone of hope and lost hope. And then we’re through, across the level crossing, clear of the town, into the country, climbing into the hills.

The grass and wheat and maize glow in the late afternoon sun, the hayfields – some cut, some being cut – shine. The top is down and I’m with a princess. We smoke and laugh and wave wildly at the haymakers. They watch us pass; some wave ironically, some just watch. When the joint’s finished, we fall silent. Sylvie becomes withdrawn. When I put my hand on hers she smiles, but it is quick and superficial. Yet the sky is clear and deep blue, and the sun is warm; the air is balmy and full of the scent of cut hay, and I am driving the princess of light.

And I am on a quest, for the first time in years, knowing, as I’ve always known but tried to pretend that it isn’t so, that you can only begin a quest alone. We’ve stood too close, Jane and I, and she has blocked out the rest of the world. Now the only thing between me and the open road is an overloaded hay wagon, and when I’ve overtaken that and darted between it and the oncoming blaring flashing ambulance, the road ahead is clear.

‘A year,’ Sylvie says.

‘Sorry?’

‘I’ve been here a year. It was just before the feu last year. There was a terrifying storm. I was staying with Rosie. I thought I’d come to Transylvania. Is a year a long time?’

‘It depends.’

‘It is. Jesus, what am I doing?’

‘You’re driving along the N99 in a 1958 2CV at’, I check my watch, ‘5.45 pm on the 23rd of June, 1976.’

‘But I’m not! I want to be, but I’m not. I’m not going anywhere. I’m twenty-five and I want to know where I’m going!’ She’s shaking. I put my hand on her arm and say:

‘Let’s stop for a drink.’ We’re driving through a village whose stuccoed ordinariness and emptiness Utrillo would have relished. I pull up at the small bar tabac, next to a large articulated lorry. On the side of the lorry is an enormous picture of a smiling Marianne in peasant costume, with the legends “La Rouergate”, and “produits de porc”.

It is very dark inside. An old man with a big white moustache and a beret like a large black plate is eating saucisse with an Opinel. At the far end of the bar the local drunk shakes over his rum. Between the coffee machine and the tissanes the patronne and the lorry driver are deep in conversation across the bar. She has short blonde hair, brown at the roots, a doughy face, moist, puckered lips. He is squat and hairy shouldered and has on a blue vest. Eventually she turns, looks Sylvie up and down, then turns back to the man, and serves us without looking again. We sit at a small iron and marble table by the silent jukebox. The marble is cool. From inside outside looks over-bright and bleached.

‘So why did you come here?’ I ask.

‘Rosie was always writing “come on, you’ll love it” – you know what she’s like – and I convinced myself it would be a new beginning. The South of France looks inviting when it’s raining in Bradford. It seemed a way out of an impossible situation – “with one bound she was free”, and all that. A lousy teaching job, an affair with the wrong bloke – the married one – that was going nowhere. The usual. And here I really seemed to have landed on my feet at last. Within a week I’d met Jean-Jacques, found the job and the flat. But sometimes, when everything happens just right, it’s wrong; it traps you. That’s how I feel now.’

‘Midsummer,’ I say, trying to sound encouraging. She laughs and says:

‘Let me tell you about Midsummer.’ Again the West Country burr. ‘When I was twelve I got up before dawn and washed my face in dew and changed my name to Sylvie because I wanted to be married to Johnny Halliday. When I was fifteen I sat on Cadbury Hill all night, waiting for King Arthur to ride out of the hill. He didn’t. When I was sixteen I was up there on my own, in the afternoon, watching the clouds in the blue sky, dreaming my way along the horizon, when I saw a flashing light. It flashed for a while, then stopped. Then it flashed again, closer. It was coming towards me, across fields and hedges, up hill and down vale – towards me! When it got closer, I saw a man was carrying the light, a tall man with a golden beard and long, golden hair, wearing flowing robes, striding steadfastly. Merlin! He carried a staff with a silver top – that’s what flashed, in the sunlight. He walked towards me, up the final bank, over the rampart. It was happening, all those dreams were coming true, I was the chosen one! Except he wasn’t coming to me. He was coming to where I was sitting, the centre of the hill. But that was near enough, wasn’t it? He was walking a ley line, to Glastonbury.

‘He had a thick Brummie accent, lousy teeth and acne. I went with him. Just took off. In the middle of ‘O’ levels. Can you believe it? But the world was Love, and I wanted to be part of it, and here was my guide. Up till then my dad had been my guide; but I’d seen that he was leading me towards what he wanted for me, what he had done, another step up the social ladder, more of the same – but it hadn’t made him happy, so why should it me? I didn’t want more, I wanted different.

‘I sewed curtains into a kaftan, I wore beads and bells, we lived in a tepee. The bloke passed me on to one of his mates but I didn’t mind. The men were bastards but the women were great. And after being so rigid, everything was suddenly fluid, and moving so fast. And no right angles, all curves – time curved, space curved. I smoked, dropped acid, seemed always to be on the edge of some marvellous revelation … Jean-Jacques says: in the sixties there was alchemy; now there’s just chemistry. Does that make sense to you?’

‘Yes.’

‘The police took me back of course. My dad couldn’t speak to me. Maybe that’s why I can’t go back now – after putting it all back together, for him to see I’ve Humpty Dumptied again.’

She stares into her glass. The old man is eating tripe now, slurping it noisily through his moustache. The drunk tries to join in the conversation at the bar but they ignore him and he returns to his solitary mumblings. The patronne leans further forward, her folded arms pushing up her fat breasts, her lips mouthing the driver’s words, her eyes adoring him. He smirks and preens, now spreading his arm expansively, now leaning forward to whisper intimately. Sylvie looks up at them, and her lip curls.

‘They’ve all been bastards, the men. Except one. Met him when they brought me back. Almost my age, too. Robert. Amazing bloke – bright as anything, brilliant athlete – “headboy material”, doncha know. Left grammar school at sixteen to become a carpenter. Headmaster mucho pissed off – visions of a golden entry on the Oxbridge honours board shattered. He’s making a name as a sculptor now. His pals who’d stayed on in the sixth form’d ask him why he’d thrown away all this for a manual job. “To learn to think with my hands, before it’s too late”, he’d say. I liked that. We were good for each other – his steadfastness and clear vision, my quickness and flights of fancy. I really didn’t want to leave him to go to college, but I had to, you know? Sometimes I felt like a kite, yearning for the string to break, wanting to snip it myself. I got involved with a lecturer. Et bloody cetera. Didn’t know what I was doing, couldn’t decide. Then I had a dream.

‘There was an empty cottage we’d walk to, near Cadbury, Robert and I, tumbledown, overrun with roses and honeysuckle, very romantic. We’d tell each other stories about how we’d do it up and live there and have lots of kids. He’d do his sculpture, I’d write poetry – or do whatever I was into at the time. Anyway, in the dream I was outside the cottage, which was all done up as we’d planned, bathed in evening sunlight, roses and hollyhocks to the eves, honeysuckle round the door – I could actually smell the honeysuckle in the dream. From an upstairs room there came the faint scratch of a pen, from the workshop the tap of mallet on chisel, even and reassuring. Then there was a noise behind me and when I turned round I saw the whole side of Cadbury Hill had slid away and there we were, Robert and I, and loads of children and friends, music and dancing, all bathed in a warm and joyful light that glowed from the rock walls and the jewels strewn all around. Everything I knew, everything I wanted was there, clearer and deeper than ever before.

‘Then I heard a click. I turned. By the side of the hill was a little gate, and holding open the gate was my lecturer friend. He wasn’t smiling at me, beckoning me to join him; he was just the keeper of the gate. Through the gate led a narrow path that twisted through woods and towns and wastelands, a grey landscape sombrely lit, but with sunrays illuminating far mysteries, and the path a ribbon of silver leading to a fabulous city beyond the horizon, its light glowing in the sky. And however much I yearned for the cottage, for the place in the hill, all I wanted to do was to go through that gate, follow that path. Because it leads to – the place I never reach. I snipped the string – the jolt and leap when the string parts….’ She sits in silence, head down, dark.

‘Which you haven’t reached yet,’ I find myself correcting. Why do I do that? I don’t know whether I want to save her or join her.

‘Right, okay, why not?’ lifting her head, voice bright. ‘Come on, I want to be there when they light the fire – I want to light the fire! I want to have a good time. Come on,’ and she’s off. As she passes the drunk he sees her for the first time and his eyes are like saucers and he mumbles:

‘Reine, princesse,’ and giggles helplessly and his eyes adore. She stops, looks at him hard, kisses him on his ugly forehead, says:

‘It’s your choice, buddy,’ waits, shrugs and is gone.

The old man is tucking into a big plate of green beans. The patronne and the driver don’t even see us leave. I dash after her, into the dazzling light, the warm, expansive evening air. Into the car, on and up.

* * *

As the road rises and we get higher there are fewer fields of cereal and more pasture, fewer vines and more woodland. At last the road levels off and we are driving across the plateau. In the distance the land rises higher, to the dry hard centre of the Massif Central; but we are not going that far. Soon we reach the dolmen where we will turn off and drop down into one of the valleys that cut into the plateau, wherein dwells the secret life of the region.

I stop by the standing stones and switch off the engine. I’m about to speak when there is a commotion by the ancient grave. A buzzard rises heavily, driven by the sharp beaks and harsh cries of three crows. It tries to return but its curved beak is no match for the snapping crows, working together, hyenas of the sky. It circles a couple of times then seems to shrug and give up its kill and wheels slowly, disdainfully away. After a short distance it begins to glide in a circle, rising with each circuit, not moving its wings except for small adjustments of wing tips and tail.

‘It’s found a thermal,’ I say. As the crows squabble over the tiny carcass the buzzard flies effortlessly and majestically higher in a medium that is its own, into the blue sky. As we watch it spiral upwards, I tell Sylvie of that first visit to France, of what happened in Albi.

‘All I’d done, through travelling here, was exchange one set of clothes for another – more suitable, a better fit, of cosmopolitan cut, but still clothes: but I wanted to be naked. I’d heard more music than I’d ever heard before: what I wanted was silence. I wanted to see – what is. So instead of heading home, I cycled out of Albi, up into this unknown region, without history. Where it seemed the only memory and meaning was in the rocks and vegetation and animals and people, and where, for a few hours, or a few days – I’ve no idea how long, in my memory it’s timeless – I lived. Just that – lived, in the here and now. And for the first time – how can I put it, words are so unreal – the inside and the outside touched. Nothing was the same afterwards.’

The crows have finished their meagre meal and are perched on a stone waiting for something to happen. The buzzard is now very high, a tiny cross spiralling upward.

‘They have perfect vision,’ I say. ‘Imagine what the earth looks like from up there. The eagle’s view. The only creature that can look into the sun without being blinded. When it’s old and its eyes grow dim, it flies up to heaven and dips itself into a fountain that renews its sight. Maybe that’s where that bird is going.’ The vast blue sky, and the tiny speck, still going higher. Maybe it can see Jane’s train crawling towards Paris.

‘Later I read about tribal initiations, in which the young man leaves the tribal territory and suffers privations until at last he sees, in a vision, his totem animal. I suffered but – maybe there are no spirits anymore – all I saw was myself. But nothing was the same afterwards.’

Sylvie has listened in silence but I’ve sensed her growing impatience.

‘But you came back!’ she cries. ‘You left what you call your ‘tribal territory’ again, and you came back to the foreign place, years later. And what’s more you didn’t come alone and naked, to the unknown; you returned with a wife; and you came armed – with money, skills, ideas. Why did you come back? To colonise it?’

‘No, to share it.’

That’s what I say. It’s what I believe. But I don’t know if it is true. And now it feels raw and exposed up here, on the plateau, and I can’t stand the eagle’s pitiless eye. I start the car and turn off and head down, between two shoulders of land, into the valley. We drive through a village with red geraniums planted in old tins, where hens scatter and dogs bite at our wheels and widow-weeded women in crumpled stockings and carpet slippers stare blankly at us as we pass. I drive slowly behind a huddle of nervous, bell-tinkling sheep being brought in to be milked. Just before we reach the river I turn off, along the rough track that leads to Edvard’s place.

Chapter 5: Approaching the feu

I park by the other cars, the usual mix of ancient and modern, of sensible, outrageous and clapped out, reflecting the inclinations and circumstances of their owners. There is no one about. We smoke a strong joint then set off along the track towards the house, weaving dreamily. Sylvie slips her hand into mine. It is small and bony; it is the only sense I have of her, her step so light and her movements so self-contained that all I am aware of is a disembodied hand, and the faintest rustle of her long dress. Edvard was our first visitor. (No, the second – the police came first, got us out of bed, to check our papers.) He knocked on the door as we sat on our trunks, paralysed by the strangeness of it all, aware suddenly that our intentions had been focussed on getting here and, now here, we weren’t sure what to do, our dreams forgotten. He opened the bottle of wine he’d brought and talked about the area, the people, his work. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said, ‘it’s all strange at first. But you’ll find out why you’re here. I promise. Everybody does. And its never the reason you think.’ He had been a sculptor. Now his place is his work.

Before we reach the house we come to a sign:

‘AU FEU’

pointing into the wood and, a few yards into the wood,

‘Antechamber’

‘What does Edvard have planned for us?’ Sylvie, from being languid and dreamy, is now alert and excited. She skips into the wood, beyond the second sign, turns:

‘Come on!’ she says, beckoning. I hesitate. Standing on the track, looking into the trackless wood, dependent on signs, at midsummer when the fabric thins …

‘This afternoon I almost drowned myself,’ I call to her.

‘This evening is not for drowning – this evening is for flying!’ Her voice echoing among the trees, her arms stretched out, her head back, turning on the spot, the golden woodland light diaphanous around her.

‘Come on!’ Hands touching trunks, leaves, she walks into the wood.

‘I’m coming,’ and I step off the hard track onto the soft woodland floor and quickly catch up.

Trees all around us, tall and slender, columns in every direction. Above us the high shimmering canopy transmuting the light like stained glass.

‘Cathedrals are dreams of forests.’

We move and everything moves. We stop and all is still; and then a single orange butterfly peels itself off a sun-splashed rock and weaves its uneven path through our vision, our lives. There are sculptures among the trees – birds with spread wings, a mighty bear, strange abstractions. Each tree is a work of art. We examine closely the patterns of bark, look up at leafy branches spiralling into the sky. Mottled sunbeams shine down upon us, warming us and – illuminating us. Sylvie glows. There are briar roses and woodland flowers. Sylvie whispers. Leaning back against a rowan, arms spread, she sighs; and the tree embraces her as one of its own. I put my arms round an oak, press the side of my face, my ear against it, feel the strength and the pulse of it, from deep spreading roots to high-reaching branches, listen to the sap flowing. I exhale, and the long outbreath empties me of doubt; breathe in and the long inbreath fills me with certainty. My eye follows a fissured path up the trunk, and I climb the spiral of branches to the topmost leaf, leap out and breast the buoyant, light-filled air, descend a sunbeam as lightly as dandelion seed, enter the honeyed darkness of a funnelled flower … Trees stretch endlessly in every direction. And among all this sensation, there are carved stones like sudden thoughts.

We might wander at will, hand in hand, enchanted, our footsteps soft on the leaf mould, our bodies bathed in light; except that we have somewhere to go. A single bird sings close to us, a short fluting sequence of notes. It darts away and repeats the sequence some distance off. We might follow that bird; except that we have a path to follow. A path not marked on the ground but indicated by signs: here a prayer flag, there a painted leopard flicking its tail, further on a manifesto painted on cloth: “Culture is our attempt simultaneously to escape from what is, forward, and to recover what was, backward. Hence the conflict. Nature is simpler. But to live in nature, you must let it be”. A jewelled snake hanging from a branch, its red tongue flicking out and in. A motionless fox – staring at us, its triangular face a blank mask – that suddenly trots away, its fine brush parallel to the ground. We jump, then laugh at the joke of it.

We follow our path, weaving as unevenly and as apparently randomly as that butterfly, knowing that it too is responding to signals; and glimpsing through the trees other signs and knowing there are many paths and many other people in this wood, although we see no one.

And then the vegetation becomes denser, the path narrows. We pass beneath an old pub sign:

‘HMS ENDEAVOUR’

I lead in single file, the path is so narrow. From being high and light the canopy has come down towards us and thickened, so that now it is a roof close above our heads, a tangle of intertwined branches and leaves cutting out the light. And instead of trees on either side, now there are banks of earth, rising as we move forward until they are head high and sealed across, over our heads, by tangled roots. Now I’m walking through the earth, and the air is cool, and smells of damp earth and mushrooms and roots, and there is darkness, and silence, and I feel the mass of earth on either side of me, beneath me, and the almost intolerable weight of earth above my head; and yet I am safe, might walk along this tunnel forever, not seeing, not hearing, not touching: ‘Sylvie?’ No reply, of course – sounds do not travel through a vacuum; I am alone.

Walking, I swell to fill the intolerable emptiness of the world all around me, to fill the world and become the world, and am at first exhilarated, and then sickened. Walking, I shrink until I am a spore, attentive but inert, waiting. Walking, I become once more human-sized, aware of the floor beneath my feet and the walls and roof close around me, and the sound of my breathing, and the presence of Sylvie close behind me, and of my precise lineaments, the outline, the surface, the extent of my body, its well-knittedness and precise functioning, the location of my thoughts within my head.

Ahead there is a light, long and thin, like a shining pendant sword, that grows as I walk towards it, that illuminates the strange signs on the walls, that becomes a portal between this dark world and that illuminated one, a portal between two pillars that is so narrow that in order to pass through it I must thin myself to a single atom’s width, so that I can pass through the shining sword, cross the threshold; and then re-form, as a voice whispers: ‘Realisation’, entire, on the other side.

Senses assailed. Warmth, such bathing warmth. Sounds, the singing and chirping of birds, distant laughter, the sighs of breeze-moved leaves. Scents, of orange blossom, honeysuckle, pine. Shape and colour: an expanse of emerald velvet grass, flowered like a mediaeval tapestry; an immense chestnut tree, with a strong trunk and a vast umbrella of a million translucent leaves, on one side its branches merging into the wood, on the other arching over, as sure and elegant as flying buttresses, to touch the house that is as solid as a rock and as domestic as cheese. And light …

For within this frame, of grass and tree and house, is the river, below us, curving between limestone cliffs, a golden river turned gold by the enormous golden sun that hangs between cliffs themselves turned to gold by the light reflected up from the river of gold. As children we stand, fingers entwined. Edvard strides up, grinning, delighted at our astonishment.

‘That’s quite a trip,’ I say, shaking his hand. He embraces us, says:

‘Welcome – until the true mysteries return we have to make our own mysteries.

‘But you’re only just beginning – don’t stop now, go on,’ he points to the river, ‘go on, bathe in gold – it’s Midsummer Eve – bathe in gold!’ and he leads us across the emerald grass to the beginning of the path down to the river, waves us on down the path.

We pass others returning, exchange greetings, but when we reach the river we are alone. At last, standing by the river, watching it flow, speech returns.

‘I feel like a kaleidoscope,’ I say, ‘that’s been shaken, and shaken, then shaken again.’

‘He’s a true shaman,’ Sylvie says quietly. ‘Inside I feel empty and clean. Now I need to swim, to strip off this old skin.’

I take off my sandals and walk across the warm clinted limestone pavement to the water’s edge. The river flows steadily. The sun has begun to redden, the shadows are turning purple, the sky becoming mauve. Spread out on two great boulders are costumes and towels. Chalked on the stone is the single word: ‘definition’. We change quickly.

The bathing place is an inlet beneath the cliff. The pool is very deep, its smooth stone sides disappearing into green depths. The water is very clear, very cold. I walk in, at first shocked by its coldness, then enclosed by it, my hot skin soothed by the water, my body shaped by it. I swim with long, easy strokes, dipping my head into and out of the water. Sylvie has climbed up the cliff. I see her above me as I lie on my back, brace myself as she plunges down towards me, feel the shock wave as she knifes into the water between my legs, watch her black and ivory form arrow down.

I follow her. We twist and turn around each other, naiad and otter, now descending into dark depths, now speeding upwards towards light and bursting into the warm, soft air.

Then we swim separately. In the depths I see a spring, Pieter’s resurgence, bubbling into the pool; at the margin I see the silty river slide powerfully by: but I do not touch it. Swimming on the surface, looking down, I imagine letting go and sinking slowly to the bottom, watching the flickering light fade as I sink, lying on the soft sand staring up until something irrevocable happens. ‘No, that’s old stuff,’ I tell myself, and swim vigorously until the feeling fades.

I lie on my back on the surface of the pool, at its centre, cold depths below me, warm air above, content to be where they meet. Maybe that’s it. Maybe that’s all there is. I swim to shore, climb out onto the warm rock, and lie in the sun, eyes closed.

I hear Sylvie sit down beside me. I hear fumblings of clothes. She sighs. I open my eyes. She has pulled the black costume down to her waist and she is lying on her back, arms stretched above her head, breasts tumbled either side of her firm chest, nipples pointing to the sky, absorbing the last rays of the sun. My eyes follow the lines of her, from her strewn fair hair to the tangle of black at her hips.

‘It would be so easy, wouldn’t it?’ I say quietly.

‘No, I don’t think it would,’ she says, eyes closed. ‘It might be nice, and it might be good, but,’ she opens her eyes and looks across at me, ‘it won’t be now.’

‘But…’

‘It’s not just a matter of opportunity, you know. Is your life that accidental? Because if you’ve been planning this, I want nothing to do with it. We’ve brought each other here, that’s what matters, that’s the moon; us fucking would just be the finger. As for the future – who knows? Come on, I want to prepare myself before the bonfire is lit.’

Chapter 6: Le feu St Jean

We are standing in a semi-circle, around the unlit bonfire, looking out over the river, waiting for the sun to set. Edvard holds a burning torch in his right hand. As the red sun touches the river, he begins to speak:

‘This is a special day, a day when we can renew old friendships and make new ones. When we, who most of the time lead isolated lives, can get together, share ideas and information, come up with more and better ways to cooperate. Because we’re going to have to cooperate to survive – forget Darwin, remember Kropotkin! We each have our personal reason for being here, a personal vision, and to be strong we need to share these visions.

‘And it is a time when we can remind ourselves why we’re here, why we have come from different places, different former lives, to this abandoned corner of Europe. And it is this – this is the place we can do what we have to do, become who we are.’ The sun sinks into the river.

‘But there is more to it than that. We don’t want just to escape from a culture that has had its day and is going down the pan – we want to show them a way of life that will work, a sustainable, ecologically-viable life, in which human relationships and art aren’t peripheral, they’re central. They call us marginaux – we’re not, we are one of the new centres. Let us light a beacon to show them!’

The sun has gone, beginning the shortest night. The buzzard begins its long descent. Edvard is about to plunge the torch into the heap of sticks but then he turns and flings it into the air. Sylvie leaps high, catches it and, her face lit by the flames, radiant, plunges it into the heart of the pyre. We applaud, cheer, embrace those around us, wish each other well. ‘Light catches fire,’ Edvard murmurs, then out loud:

‘Food! Drink! Let’s enjoy ourselves!’

There are about fifty people here. At first, after extravagant greetings and embraces there is awkwardness; the fire is so small and the sunset so magnificent that there is nothing to draw us together. People stay in the couples or groups they came in, or soliloquise silently. But as the sunset fades and darkness spreads across the sky, as the fire burns up and lamps and torches (no electricity tonight) are lit, as the night closes around us and the stars begin to spangle the dome of the heavens, people come to the fire, relax, separate and mix, become involved in conversations. Expectations are gradually forgotten, the unexpected happily accepted. The feu St Jean is under way.

‘Kris! Come and settle an argument!’ Michael pulls me over and introduces me to his friends from England. Michael and Rosie always have lots of friends over during the summer:

‘Willy says that Richard Fariña was married to Caroline Hester. I say it was Mimi Baez.’

‘Both. He was married to Mimi when he died. And what’s the greatest novel of the sixties? Been Down so Long…’

…it Looks like Up to Me!’

‘No, it’s got to be Gravity’s Rainbow,’ Willy says.

‘Trout Fishing in America,’ Rosie says firmly. I sidle away, leave them to their nostalgia.

André is holding forth about the Tibetan diaspora being as significant as the Jewish:

‘As with the Jews, an intense, inward-looking, religion-centred people have been driven out of their homeland – in this case the land of MU, centre of spirituality – by a materialistic invader. They will carry their religion and infect us with a new spirituality – for we are as unprotected against spirituality as the American Indians were against measles. As the Jews were the agents of the Piscean Age, so the Tibetans will be the agents of the Aquarian.’ Marie-Claire listens patiently with the others, looking respectful, loyal and bored. She flashes me a quick smile. André holds out his hand as I pass, we shake, he doesn’t miss a beat.

Fred is sitting cross-legged, drawing the plans for a composting toilet for the serious young couple with the baby who have just bought twenty acres nearby:

‘It’s important to remember that it works aerobically not anaerobically,’ squinting seriously at them through taped-together spectacles. ‘Conventional sewage systems are anaerobic, hence the smell. In fact one of the central differences between alternative and conventional biological technology is that ours is aerobic based, theirs is anaerobic … ’

Jean-Luc and the group of young French who rent “Carbonniere” are chortling over their latest supermarket scam: you pay for a trolleyful of goods, empty it into the car, refill the trolley with exactly the same goods plus a packet of biscuits, at the checkout you show the receipt and pay for the biscuits; half price shopping. It joins their ‘hire a car and swap the engine’ trick as a way of getting something without paying for it. How do I feel? They collect State handouts when they can, spend lots of time working out schemes to cheat big institutions, are always confronting, always getting busted. Are they freeloaders, or revolutionaries? Are these acts of guerrilla warfare against a political and economic system they want to destroy, or selfish acts that we have to pay for? It depends on where you put your politics. I realise, uncomfortably, that I want neither to confront nor to conform to the political-economic system; I want to be invisible to it….

George and Amanda walk by, their five children following like goslings. They live in a tiny barn, without electricity, a hundred yards from water. Their garden always fails and they live out of the local shop on the considerable family allowance the French pay to large families. His occupation in his passport is ‘poet’.

I look around for Sylvie but she has disappeared, so I get a bottle of wine and some food and sit by the fire and look around.

What do we have in common?

We are all arrivés, installés, strangers, incomers to a region which has known only emigration for hundreds of years, with a population less than half what it was in the fourteenth century – look at the number of empty buildings, at the hillside terraces, once cultivated, now buried under scrubby woodland. We are going against the trends by emphasising self-sufficiency in a community which is becoming ever more tied into the market economy.

Our self-sufficiency derives from ideas learned in the cities. We proclaim a modern self-sufficiency, based on scientific theories: the locals remember subsistence as back-breaking toil and grinding poverty. We say – ours is a way to a richer life: they remember shortages, privation, poverty, and see money as the only enrichment. We say – your life as peasants has been so hard because of politics, because you were exploited: they say – okay, it’s because of politics – but who’s going to change the politics?

And the locals are not here tonight; they’re at home watching television, or at a dance listening to electric music. And we, with the electricity switched off, are an island, imagining the outside world away. But aeroplane lights blink among the stars, tractor headlights shine in the distance, cars accelerate noisily along the riverside road, and a train draws into Paris-Austerlitz, and a lone figure descends … don’t look at the flames stretching, disconnecting, disappearing: concentrate, stare into the fire, seek your future in the white-hot stillness inside the leaping flames….

‘What do you see?’

‘Hendrika! I didn’t realised you were here. No Pieter? Sit down, have some wine.’ She is Dutch, a handsome, middle-aged woman, capable, tired. ‘Flames, just flames. What do you think, about Jane going?’ Wanting allies.

‘I think she was very sensible. And you think, what – that she’s weak, she’s betrayed you?’

‘It was the only thing to do. We were blocking each other so. But I think maybe she’s betraying La Balme, our ideal.’

‘Perhaps it isn’t her ideal.’

‘Perhaps she has no ideals.’

‘Steady, you’ve jumped a lot of steps there. Men are very good at having ideals – or ideas or fantasies or delusions – and dragging women into situations in which the women have to do the coping. And people do stupid things when they love someone. If they’re lucky they realise how stupid and do something about it before they are irretrievably harmed, or all their bitterness is heaped on the loved one. You think she’s being weak and selfish. In fact she’s giving your lives a chance – she’s giving you a chance.

‘To do what?’

‘Only you know that. Maybe to examine your reasons for coming here. Maybe to be alone. Maybe to do something. Only you know – and if you don’t, you have to find out.’

‘Pieter says I have to make a home.’

‘Maybe, maybe not. Hey, don’t look so serious!’

‘I want to get it right.’ But all I want, at this moment, is for her to wrap her middle-aged arms around me and bury me in her bosom.

‘Where’s Pieter?’ I ask. She looks across at the gorge and the cliffs, black against the sky:

‘Out there. Looking for the cave. He thinks maybe the midsummer sunset will give him a clue.’

‘The cave?’

‘You don’t know about the cave? Ask him to tell you sometime. In South Africa, when he was young, he found a cave. Now, after so many years in the Netherlands, he’s sure there’s another one, here.’

‘What do you think?’ She smiles:

‘The Dutch don’t have caves.’

‘Maybe they should.’

‘We don’t have much choice. But maybe it’s why we went to South Africa, and the East Indies, and South America. And the Aveyron, of course.’ We laugh, then sit quietly watching the flames lick round the branches, the heart of the fire whiten. I feel safe with Hendrika. I ask:

‘Are there different sorts of fire?’

‘There is fire that burns, fire that consumes, fire that purifies. The fire that falls incessantly on Capaneus in Dante’s hell is surely different to the fire of Donne’s “Oh burn me O Lord, with a fiery zeal, of thee and thy house, which doth in eating heal”. But maybe the fire is always the same, the difference lies in the thing being burned. Maybe it depends whether you are ore or wood. Or flesh. And which you want to be.’

‘Thoreau writes: “I ask to be melted. You can only ask of the metals that they be tender to the fire that melts them. To nought else can they be tender”.’

‘Mmm,’ she says, staring into the fire, lost in thought for a while, a peaceful time, then says sharply:

‘But stop asking me such interesting, irrelevant questions and go and find someone young to talk to; go and do something! I’ll be going soon anyway – we’ve a pregnant cow that can’t be left too long.’

‘Thanks for the chat.’

‘Come over for a meal, soon. Pieter likes to see you.’ I heave myself up and leave her staring into the fire.

* * *

Now the party is in full swing. Edvard plays the accordion and we dance energetically. There is a circle dance of changing partners, and when Marie-Claire whirls past she whispers ‘see you soon’, smiles and is gone. There is no sign of Sylvie.

When the dance finishes I drift away, to the edge, and look around. Two figures stand close together by a tree, silhouetted, talking earnestly. The French outlaws and the English trendies are in vigorous conversation. A looser group waits in gentle anticipation as someone tunes a guitar. The wine is singing in my head and my body feels good from the swim. The evening air is soft on my arms.

The bonfire is burning well now. How carefully Edvard has combined his bonfire ingredients, like an alchemist: cherry and apple for their scent, pine for the sparks, holly for quickness, ash for longevity; and the aromatics special to this night: thyme, rue and penny-royal. The smells of the bonfire smoke mix with the night scents of flowers and green vegetation and the resinous pine torches.

Shadows flicker extravagantly in torch- and fire-light. The Milky Way bands the sky, and the newly risen moon is a pendant pearl. There is the whisper of air in the trees, the murmur of conversation, the sound of guitar strings being plucked and strummed hesitantly. I can feel the still, dark woods all around us, the flowing river not far off, the rocks still warm.

It is a night on which I can begin to remember, and believe in once more, my dreams. It is a fine night, Midsummer Eve, to let all thought chatter, then fall silent, to allow a quieter voice, so often unheard, be heard.

And then Marie-Claire begins to sing. Alone and unaccompanied, eyes closed, her voice at first flat, cracked, limping earthbound; we shuffle self-consciously: and then suddenly taking off, as if mirroring up from reflection to reflection of flickering light, from eye to decoration, along boughs to the highest leaf and then up with a rush to those still lights so far above us, across the face of the moon and from star to star. I don’t understand the words she sings, but all I hear is ‘why?’ When she ends there is silence and then, as we collect ourselves, murmurs of appreciation.

Edvard sings, to a chunky guitar accompaniment, a lively song with many verses. From dreaming I’m suddenly wide awake as I listen to the unfolding story of the boy and the girl on Midsummer Eve. The girl says – dance with me, leap over the fire with me, unite with me, for our union tonight will be magic and blessed. The boy says – no, I don’t know you, you might be a fairy, might give me ass’s ears; tonight I must stand alone and await the revelation. And so he stands, proud of his vigil. But there is no revelation, and in the morning, when he searches for her she is gone, and the fire cold ashes. An old man now, each year he keeps the vigil, and sees only her face in the midsummer moon, and hears only her voice in in the crackling air echoing ‘why not?’

Even as the sound of the guitar dies away and the applause begins, I am turning and heading away from the fire and into the wood. For suddenly I know why I am here, what today has been leading to. I know that she is there, waiting for me. I know Sylvie is at the centre of the labyrinth, waiting. ‘Why not?’ rings in my head; ‘yes’ I say, and plunge on. In spite of the dark I know exactly where I am going, guided by the trees – here a holly blocking my path, there a broom pointing the way, barriers, tunnels, avenues – and the attraction of Sylvie.

I burst through the final barrier between us – and am teetering on the edge of a long drop to the river. I curse myself for my unseemly haste, for not having watched carefully for the signs.

I move quietly now, observant, and soon I am in Edvard’s labyrinth. And now I can feel her: when I follow a path away from her, I feel myself tighten and grow cold; as I approach her I open and warm. Lights ahead. My heart beating fast. I arrive at the small clearing at the centre of the labyrinth. Sylvie is there, I know. Sylvie is there, I see. Not alone, waiting. With someone. Being fucked.

Chapter 7: Midsummer dawn

I wake suddenly, stare up into black emptiness, happily empty; feel memories slowly precipitate in my mind; begin to sift them. Sylvie at the centre of the labyrinth, lit by flickering torches, leaning forward, her hands white knuckled, braced on the omphalos, her hanging breasts out of her dress shuddering with each impact, her skirt up over her white hips; Jean-Jacques, dark hands on those white hips, thrusting into her from behind. He bearded and yellow eyed, hairy buttocked. She pale victim – and yet grunting at each thrust, squirming on him, pressing back onto him when he is fully buried, gasping ‘oh yes’, ‘oh more’, ‘you bastard’, ‘oh more’. Thrust ‘bitch!’, shudder ‘bastard!’, thrust ‘bitch!’, shudder ‘bastard!’, thrust ‘bitch, Oh God, Oh Jesus, Oh Hell, oh….’ ‘Stay in, I’m coming, stay in, stay in!’ I turned and staggered away as they sank entwined next to the navel stone.

I had seen – what? Two people, a couple, fucking. But I wanted, as I rushed away, through the grasping vegetation back towards the fire, I wanted it to be more than that: a mythological rape; a sacred ritual for which, if I had been discovered observing, I would have been hideously done to death. And when I reached the edge of the wood and looked at the scene around the bonfire, the flames leaping and the figures dancing, the couples standing and lying clasped and still, the cries and whoops and the brandished bottles, I saw an orgy, and looked around for the golden calf.

Then Rosie took me by the arm and sat me near the fire and gave me some wine; and the fire and the wine warmed me, and in the light I saw smiling faces, people dancing enjoyably, talking animatedly, good naturedly enjoying themselves. And after all, Sylvie and Jean-Jacques were lovers. And after all, I had come as her companion, her paladin, not her lover.