Day 19: Belcastel to Albi, 51miles.

The first smile of the South. Dante and tripe. ‘Benveguda en Tarn’. Pink city. Crusade against Christians. A congregation facing hell. The great explorer lost. Diagonals of the Hexagon. The garden restaurant. Burger à point.

It is another cold night and I hardly sleep. I’m up, packed and ready to leave long before anyone is about. I decide that Belcastel can live without my camping fee, whatever it would have been, and push my bike up out of the village.

It is an expansive June morning, the sun up long before people, the blue sky vast, the untenanted, uninfringed air rich with oxygen as I breathe deeply in and of the silence. Detail. The last wisps of mist are dissolving from the tops, going, gone. Now just green and blue. The quiet munching of a horse by a gate, the shiver along its back and the shake of its head as its big eyes follow me before it returns to its munching. There are simple roses in the hedge, small, delicate, pink. Again, I’m full of memories from living here. Of cutting a branch of ash for a hay-rake handle, stripping the bark off the damp, bone-white wood, splitting and fitting the handle in the chestnut head, the work unfolding perfectly, all this to a chorus of bantam cocks one early midsummer morning before the neighbours’ alarm clock had shaken them awake. Standing on the top, and seeing my shape cast on the snow-like mist below me, surrounded by a rainbow nimbus, a glory – what was it, what did it mean? Years later I discovered it’s called a Bröcken spectre.

But now, as my thoughts have been meandering, my footsteps, pushing the bike, have wandered. I’ve no idea where I am. I am in a maze. Every tiny lane looks equally important, there are no signs, the lane that begins upward, around the next corner curves back down. I return to the crossroads several times, once even back down to the village itself. Should I have left a camp-site fee? Is this Hermes’ early-morning trick, a little pipe-opener for a day of mischief? What to do? Keep trying.

After two hours, I emerge unexpectedly from the maze, onto the D997, at Colombiès. I am back on the map. I head south, to the junction with the D911. I am at 750m, today’s high point. The land falls away, spreads before me. This is my ‘first smile of the South’.

I pass a roughly-painted sign by the road, “NON AUX EOLIENNES. IMPOSTURE ECOLOGIQUE.” ‘No to wind turbines. Ecological imposture.’ How French, on a protest sign, ‘Imposture’!

And a small, new factory unit, ‘Tripous. Fabrication. Vente directe’. In English ‘tripe’ means rubbish; in French, trickery. Hermes must be the patron-saint of French tripe-dressers. The best tripe I ever tasted was in a sandwich, peppery and hot, on a thundery summer day in Florence, between heavy showers, outside the church where Beatrice is buried (so many notes left to her, in a bowl in the church; as I considered leaving a note, wanting an answer that tumultuous week), close to Dante’s house. We had a tripe shop when I was young, the last tripe shop in town, bleached seams slithering around on the marble slab in the sun-filled window, and billowing like formless albino marine creatures in the vats of water in the yard. The young woman at this establishment has returned to the family farm to ‘devote myself to tripe’. As well as selling it fresh, they can it. Tinned tripe? Do the trotters they sell here come from the pig factory, the abattoir I worked in? not far away, now.

Heading south and down, a wind at my shoulder, pushing me on, the whole of the South is spread before me, light-filled air, ochre and green fields softening in the distance to a misty blue. There is one last sharp reminder of the west-draining streams I have been crossing for days, as I descend to and climb up from the Viaur.

Then I cross into Tarn. Which markets itself as ‘Coeur d’Occitanie’, and welcomes me ‘Benveguda!’

The buildings change, it seems at the département boundary, from grey stone with steep roofs of scalloped grey slate, to ochre render and shallow red-tile roofs. And the road margins, I’m sure, lose definition, from road to verge, from verge to field. There is something altogether looser about the South. For as well as crossing a département boundary, I have crossed a pre-1790 Province boundary, out of Guyenne-Gascogne. I am now in Languedoc.

I pass through the village where a friend and her new husband came to live, make a new life together. He liked it, she didn’t. She went back, he stayed. They divorced.

Through Carmaux, but no time to visit its museum of mining. And there, at last, is Albi.

For miles, on the long straight run into Albi, the cathedral is visible. Side on, high up, it is a huge presence, dominating the town, a red brick oblong with what looks like a fat chimney at one end, industrial-looking. An appropriate look for a church that imposed its rule with such factory efficiency. And for a building built to be a constant reminder to the people below of the ever-ready ideological machinery within, and its power to torture and burn to death at will.

I stop at the bridge over the Tarn. It is a lovely view: the wide river, crossed by the two rhythmic-arched bridges and the diagonal weir, fringed by dark trees, the town heaped up in attractive cubist geometries, the cathedral sailing high. I had forgotten how pink Albi is! The raw red of the ubiquitous brick mellows with age, and the pale mortar further softens the effect. It has a dusty, rosy, salmony pinkness, set off by the green tinge to the river, the white water off the weir, the Midi blue of the sky.

Before I enter the town proper, I pause to ponder which Albi I am entering.

There is our market town forty years ago, where we would drive once a month in our ancient, canvas-seated 2CV to stock up in the whole-food coop and Mammouth hypermarket, have long, hot showers, and visit like-minded friends in the old quarter.

There is the town I recorded and reinvented in a novel.

There is the fourth major town on the Meridian, the fourth medieval cathedral, another chakra on the spine of my journey, and my entry point to the South.

And there is the town that gave its name to a heresy and a crusade, that colours so much of my relationship with the South.

All are interfolded, with abrupt shifts between. I cycle across the bridge, and up to the cathedral.

The Albigensian Crusade, the first crusade against heretics rather than infidels, was proclaimed in 1208 by Pope Innocent III. (I note the names popes give themselves, that allow them to distance themselves from their actions.)

It happened because of a coming together of interests. The result was a war of atrocities and destruction that ravaged the South for thirty years, followed by eighty years of the Inquisition, in which tens of thousands were slaughtered and thousands burned to death. A Christianity closer to the original Fathers, and a culture of subtle traditional relationships and high artistic achievement (celebrated by Dante) were destroyed.

The French crown, the French state, colonised the South.

Its name was less because Albi was the centre, than because the Cistercian fanatic, later Saint, Bernard had received a notably hostile reception when he preached here in 1145.

Albi fell in 1209 without a fight, after the massacre at Béziers.

But in 1234 the Albigeois, outraged at the torturings and burnings by the Inquisition, forced the bishop to hide in his own cathedral.

His successor, Bernard de Castanet, was made of sterner stuff. He had both religious and secular power, and this was useful because, although the church pronounced on heresy, the state carried out the sentence. Bernard was judge, jury, and executioner. He was the Inquisitor for Languedoc, and a close ally of the Dominican Inquisitors.

His first act was to build in Albi a fortress-like bishop’s palace, la Berbie. This was his base, and also a detention facility for the Inquisition.

By 1287 he felt powerful enough to pick a fight with the town, increase church dues ten-fold, and begin to build, using these dues, a new cathedral, modelled on his brick palace-fortress.

What to make of it, this church-fortress? It is huge, towering, impregnable. But impregnable against what? It comprises twenty-nine round buttress-towers, connected by curtain-walls that rise sheer and blank to lancet windows fifty feet up. The walls are topped with battlements. It is unlike any other cathedral. It is the largest brick building in France, possibly Europe. (Who has counted the bricks?) Although each canny Albigeois could count the bricks his taxes had paid for. While he remembered the Hebrews in Egypt, making bricks for their masters.

At the same time as the followers of Suger were building Notre Dame in Paris, with pointed arches and flying buttresses and expanses of glass, flooding the apse with light and expressing spiritual aspiration, even yearning, this fortress was being built as a manifestation of the church’s oppressive power over the community.

I am reminded of another church that was built at the charge of a community and as an ever-present reminder of their defeat at the hands of authority, the Sacré-Coeur in Montmartre. That sugar-loaf confection was built in the years after the Commune. It was, perhaps still is, a tradition for the locals to spit and utter a curse as they pass.

Inside, it gets weirder.

It is a vast space. There are no aisles and it is the widest transept in France. In contrast to the blankness of the outside, the walls and ceiling inside are covered in trompe-l’oeil patterns, as if to confuse the eye and draw it to the mural on the west wall.

For in here the congregation, by some vindictive reversal, faces west, with their backs to the high altar. Like naughty children facing the wall. Except this wall they are forced to face has upon it a vast and ghastly picture of the Last Judgement. And at its centre is a great doorway, that could be the mouth of Hell itself.

Behind them, in the area from which they are excluded, which they never see, in the richly-decorated choir, the Holy of Holies, in the company of a host of beautifully-crafted Bible figures, in the presence of the Virgin and child, and in the orient light from the apse, the canons sing the holy offices. I can’t wait to get out.

The cathedral took 200 years to build, and in that time Albi grew wealthy, growing and trading in saffron and pastel, woad. Woad was the only blue dye of the Middle Ages, before indigo arrived from the East. Weld provided yellow, and madder provided red, and the wools of the great tapestries were dyed with these three.

Referring to the Toulouse-Albi-Carcassonne triangle, a contemporary wrote, “Woad hath made that country the happiest and richest in Europe.” So the cost was easily borne.

But imagine that money available to the old South, to Languedoc, to the patrons of the troubadours …

In 1794 the cathedral became a Temple of Reason.

In 2010 it was designated a World Heritage site. It is a great draw for tourists. Its image is on a million postcards and souvenirs. Like the people of Montmartre, the Albigeois have learned how to turn a profit from the instrument of their oppression.

I need a break! I walk past the white outline of a man on the pavement – art intervention? crime scene? – to a place I never visited when I lived here. (Too busy. Too serious. Foolish!)

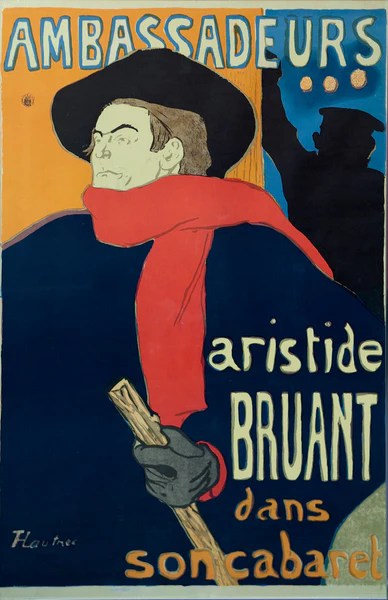

The Toulouse-Lautrec museum. In 1970s the town was decidedly ambivalent about its most famous, or notorious son, an aristocrat, but also a stunted drunk who lived in brothels, and painted prostitutes and vaudeville acts. Now he is celebrated everywhere in the town, with quotations plastered across dress-shop windows. And the museum is now in Bernard de Castanet’s Berbie. That I like!

It is an excellent museum, and I can’t stay long enough; I will have to get back to Albi: but for a while I escape to Paris, to Montmartre, to the few streets where he lived and painted. I had sped past his studio on my hectic ride across Paris, tipping my hat as I passed.

I am struck by how modern he is; less in his style than in his understanding of the market-driven metropolitan world. In his paintings of prostitutes I see his awareness of the market. Not the market for his paintings, but the market in which the girls were renting out their bodies. He depicts with shocking matter-of-factness how they are, all the time, even when they are off-duty, marketing themselves. Wearing clothes, adopting poses, taking on characters, acting in ways that will interest (‘arouse’ is too strong a word) the imagination of the client. Waiting in positions that they hope will draw his jaded attention. Each is trying to create a personal market, and thereby a buyer. There is something irremediably bleak about these pictures of girls selling access to and misuse of their bodies, in a buyers’ market.

And his awareness of the market is clear in the lithographic posters he created for artists and venues. New laws allowed bars and cabarets to open. Which meant that competition was intense, and every act, every venue, if it was to succeed, had to develop an image. The new lithographic process and cheap printing allowed these images to be fly-posted everywhere. Henri was a genius at developing images.

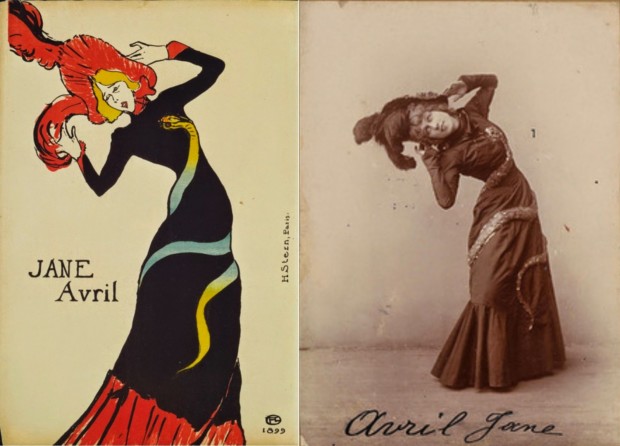

Looking at his posters for Aristide Bruant, Jane Avril, and comparing them with photographs of the artists, and the many sketches he made along the way, one sees how carefully, and brilliantly, he both captured and created, in an iconic pose, the essence of their act.

For the venues, like the Moulin Rouge, his depictions stop the action just at the moment you want it to go on – so you have to visit the venue to experience it going on. He is a great artist.

And what adds a dimension to his greatness is that, while he is depicting the artists at their most attractive, and ‘authentic’, he is showing both the frailty of the individual, and the artifice of the situation. He is depicting not the substance, but the market.

And while he was selling the acts, he was selling his artist-self – he had his own initial colophon. (Like that other great artist-salesman, Dürer.) He is the Warhol of his day. Dead at 36, younger than Van Gogh. And, to add an irony, he is remembered today much less for his paintings than for the posters that were for him the hack work that paid the bills that enabled him to paint. I return to Albi, refreshed.

To the Albi of a novel.

It had taken me a long time to dare to imagine, invent, make up, to be able to ‘tell stories’ (which as a child was a phrase used for ‘lying’), to act upon Picasso’s ‘art is the lie that leads to truth.’ It was a while before Barthes’ deconstructions in Mythologies showed me that the self-evident is simply the unquestioning acceptance of the prevailing ideology. Before I learned from Levi-Strauss in La Pensée Sauvage that different cultures don’t just express reality differently, they experience it differently. Before Harari in Sapiens showed me that myth-making, the ability to imagine, and “to transmit information about things that do not exist at all” is the defining feature of Homo sapiens.

Now to revisit the places and objects at the beginning of the novel (Diggers and Dreamers, p.9-11. See in the drop-down menu MY BOOKS.), unvisited in forty years.

The public bathhouse is still here, and a shower is still cheap, only 80c.

The war memorial is close by, and the white gravel.

The crane is long gone. It had been there for the rebuilding of the old quarter. The old quarter was rundown, overcrowded, unsanitary, poor, lacking facilities, and occupying a site with development potential. It was lively, cheap, a community with washing-lines across the lanes, plenty of eyes on kids playing in the streets, useful local shops and services. It was demolished, and rebuilt on the same street plan, not in rough stone and render, but in ‘trademark’ Albi Roman brick, with shops along the lanes, and flats above. But the flats were too expensive for the locals, so they were moved out. And the shops and cafés were upmarket, for visitors and incomers, not for a local community: boulangerie replaced by patisserie, épicerie by chocolatier, mercerie by a fashion chain, no places for tradesmen’s workshops and yards. Visitors, safe in familiarity, flock in. It has become a place that time passes through, as styles and fashions change, but that doesn’t age: take a photo, and you could fix it, years later, to a specific year’s fashion campaign.

But where is the giant anchor? Surely I didn’t dream it, invent it, the anchor, “set on a plinth, eighty miles from the sea. I sniff it to see if I can smell the sea. It smells of iron and heat.” …?

It must, I realise (how little I knew, then, about this area!) have been a memorial to le comte de Lapérouse, naval officer and explorer, native of this town, whose amazing scientific expedition to the Pacific in the wake of Cook explored and mapped the coasts of Alaska, California, Hawaii, Australia, Japan, Korea and Russia. He sent back his invaluable records with the English from Australia, then disappeared. His last message said he expected to be back in France by June 1789. Just in time for the Revolution. (Apparently a benevolent and just captain, what role might the returning hero have played in making the Revolution work …?) After many searches, remnants of his ship were finally found in the Solomon Islands in 2005. But I don’t find the anchor.

I have remapped the Albi of memory and invention onto its present actuality. It is a town busy with commerce, busy with tourism. And, at this point in the late afternoon, busy with children. Because the streets have been roped off and waiting zones established for an evening of children’s cycle races. Disorientated, I stare at my tourist-office map, trying to work out where my night’s lodgings are.

As I peer hopefully around, I become aware of a young man sitting, staring at me. I say, hi, and he clicks into life, as if he’s been waiting for me. He scoffs at my tourist office map and pulls out his own map of the town. He asks where I’m heading, indicating my bike. I say proudly, to Perpignan. From Dunkirk. ‘Ah’, he says, unimpressed, ‘une Deeagonaale’. What? Others have done this? He recites the six Diagonals, bike routes across the Hexagon, between Brest, Dunkirk, Strasbourg, Menton, Perpignan, and Hendaye. They are organised, I learn later, by Amicale des Diagonalistes de France. Each has a time budget. Dunkirk to Perpignan is 100 hours.

He tells me how to get to my destination, and sits back down, inert once more. As if he is an automaton waiting to be switched on. Or an actor awaiting his cue.

He is another of those characters, like the woman at Saint-Denis station, the young man in Epignay, the man in the square in Pithiviers, who seem to have been placed, either to guide me, or to lead me astray. Spirits of Hermes, of the hermetic path. Was this character’s role to deflate me? To show that what for me is something special, is in fact something ordinary? And by extension to make me ordinary? Or was it to stimulate me to say, defiantly, this is my particular journey, my own diagonale, that I fully acknowledge and own …?

I find my lodgings. An odd word to use, but it is neither hotel nor hostel, an informal conversion of a two-floor flat, with individual bedrooms and a big shared kitchen.

It is good to be back among people, even if it is with that awkwardness of difference of language and type, and the simple desire in each of us for privacy. An old French couple, who seem to have taken up residence, the wife having that way of turning every place into a version of her home. A woman on her own who seems to want to talk, but at the same time has a way of deterring conversation. But it is good to be inside, a solid building not a flapping tent. And my room is comfortable, and it has a decent bathroom, I can shower, do laundry and sort out my things.

I bring my bike into the lobby, and put it in the cellar. The building is the classic nineteenth-century block of apartments, the provincial version of the block in Perec’s Life A User’s Manual, which opens, “Yes, it could begin this way, right here, just like that, in a rather slow and ponderous way, in this neutral place that belongs to all and to none, where people pass by almost without seeing each other, where the life of the building regularly and distantly resounds.” The heavy outer door that slams shut no matter how carefully you try to close it; the bare, dark, neglected lobby undecorated for half a century; the stone staircase of uneven, worn steps spiralling past door after door; the sounds and cooking smells of different lives seeping out from behind each; big locks and big iron keys; the curved wooden handrail loose on the iron holders; ancient light switches. The general neglect that enables cheap living now, on the capital (including labour, of course) expended when it was built.

Having showered and changed, I go out. The heavy door slams. I stand on the street, by the big elaborate coach doors that lead into the block’s courtyard, watched by the glittering eye of the amateur concierge behind the lace curtain.

Which way to go, in search of a meal? It is a long residential street, tree-lined, the evening sun dazzles along its length, the evening is pink and warm. There are a few shops but most of them are closed down. Do I want to go back into the centre? Too fashionable, too far. I want a quick meal. There is a burger place across the street.

Not a plate-glass window Formica place, with grudging sitting space, but a small restaurant that has adapted to the modern eating habit that demands burgers.

The small, energetic woman ushers me through the dark empty restaurant, with its candles in wine bottles and gingham tablecloths, into a garden, shaded by the buildings around, with a couple of trees, mild and comfortable. Oh, this is surprisingly nice.

I order cheval burger and beer. How do I want it cooked? she asks. I say ‘moyen’. ‘On dit, à point’, she says, less correcting than informing, nicely done. Of course! I’m mentally kicking myself for having forgotten. Then I remember Barthes’ essay on steak-frites, how bloodiness is the steak’s essence, and “even a moderate degree of cooking cannot be explicitly expressed; such an unnatural state requires a euphemism: a medium-cooked steak is said to be à point, more as a limit than a degree of perfection.”

I sit back, sipping my beer. There is a family, with a noisy child demanding attention, a listless mother, and a man who spends the whole meal on his phone, chewing as he listens, swallowing before he speaks. An old couple shuffle in, regulars on their night out. They order quickly, automatically, and then settle down to the puzzles that are printed on the place mats. Instead of tablecloths, cheap restaurants have individual paper place mats, advertising the town, or shops, or products, with, in this case, puzzles, and horoscopes. My horoscope reads, “Do not throw yourself lightly into a hazardous project. Be more prudent, your finances will be less impoverished.” This is the usual advice for the impulsive Aries. But having ignored the first piece of advice in making this journey, I decide now to follow the second: I will not have a pudding.

As I wait, I ponder something that had occurred to me while writing Diggers and Dreamers, years after our time here. What if we, having got off the train here, with our trunks, instead of taking the bus up into the hills, as we did, to stay with English friends who had persuaded us to come and do the ‘self-sufficiency thing’, preliminary to buying our own place, what if we had stopped in Albi? What if she, who wanted to be French in France, had got a job here, teaching, or in an office. While I, who wanted to be a stranger in France, stimulated by both the difference and the freshness of a new country, had written …?

As I look around the little garden, observing, noting – the accent, panse for pense, merci bieng, the people around, local colour, the vividness of the unfamiliar – what if, instead of a year working in an abattoir (120 pigs a day, killed and processed), and a year working on a house and the land, gardening, pruning vines, scything hay, making wine, bottling vegetables, making baskets, mending tools, fixing a cuisinière with an iron plate from the blacksmith and fire clay dug from a place in the woods he told us about, struggling with an old car, roofing a house, what if I had just written?

Except that it was exactly those two years of hard manual labour, of being practical, of débrouillage (getting by) and bricolage (improvising) that had been a crash course in separating me sufficiently from my privileged bookish upbringing to enable me to reconnect to a self I had been losing touch with since I was eleven. And that in the years after, back in England, had informed my writing.

Dinner arrives. The difference between burger places in France is less the burgers than the chips. These are chunky, not greasy, excellent. I had been trying to believe that cheval burger is made of horse meat (having conceded that canard burger isn’t made of duck), but this, the second I’ve had, like the first has a fried egg on top. How did it get the name? Horse and rider? I eat well, and saunter back. The glittering eye through the lace curtain does not blink as I heave open the heavy street door.

I close the shutters, those ingeniously-designed but fiendishly complicated wood and iron French shutters, definitively old France, and am in bed before ten.

Here in Albi I have a sense of arrival. But also the sense that this is the beginning, that one focus of my journey is just ahead. Tomorrow I will head east, across the Meridian, into the hills, and revisit our house of forty years ago.