The Blut-Fin (location of the Mire du Nord, first siting post for Picard’s measuring of the meridian across France, to begin the first accurate survey of Louis XIV’s realm) was one of thirty Montmartre windmills in 1700, milling grains, pepper, spices, locally-quarried gypsum for plaster and porcelain, crushing grapes. By 1830s most had gone, as urbanisation swallowed up agricultural land and vineyards and the quarries were abandoned. Instead there were thirty bals, outside Paris taxes and control, and catering to the day-trippers escaping Paris. Zola in 1870s describes the liberation of leaving the city. They developed into the guingettes, popular taverns and dance halls. Between Blut-Fin and Radet mills, the miller Debray built the most famous, the Moulin de la Galette, painted by Renoir, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec.

In Zola’s La Curée, Saccard the property speculator is pictured here in 1851 gazing over a city turned to gold by the sunset, foreseeing “that whole neighbourhoods will be melted down, and gold will stick to those who heat and stir the mortar” (p68) as his hand slices through the air the cuts of the new boulevards that will, with his inside knowledge, make his fortune. The boulevards destroyed the centres of the unruly mobs, drove the poor out of the city, and connected barracks with the troublesome eastern districts. Fortunes were made, and the city loaded with debt that wasn’t repaid until 1929. “The largest urban renewal project in the history of the world” (La Curée pxii) transformed an unhealthy and malfunctioning medieval city into, in Walter Benjamin’s words,“The Capital of the Nineteenth Century”.

The entrance to the Moulin de la Galette, now an expensive restaurant, is on Rue Lepic, a horse-shoe road that parallels, on the south of the Butte, Ave Junot on the north. But whereas Junot is a twentieth-century road built on the Maquis, Lepic is old, and historic. And at the heart of High-Montmartre, in 18th arrondissement, distinguished from the 9th, that had been inside the the eighteenth-century tax Wall of the Farmers-General (not agriculturalists but tax farmers). High-Montmartre, the real Montmartre is the area around the Butte, where Roman gods were worshipped and Christian martyrs made, its world of cranking windmills and mystical springs, of a free and – literally – outlaw (outside the law of Paris) way of life. With an undercurrent of real lawlessness – the Lapin Agile was called Cabaret des Assassins because of a murder there. Or was that an invented tale to titillate the visiting Parisians? Like the false story that the marauding Cossacks in 1814 had rewarded Debray’s resistance at his mill by cutting him in four and nailing the quarters to his windmill sails. Even the Montmartre vineyard dates from 1920s, the last commercial vineyard having gone decades before: ‘Montmartre’ was already a ‘destination’. But it is the world of Jean-Pierre Melville gangsters, as in the brilliant Bob le Flambeur.

Rue Lepic is the old road from the Blanche Barriere, now Place Clichy, to Place Jean-Baptiste Clément (named at this highest point for the mayor during the Commune) on the Butte, curving because of its steepness. Bonaparte had it paved to ensure access to the telegraph station at the summit. Renault drove his first car up it to win a bet, and gained 12 orders, which founded his business.

And 54 Rue Lepic is where Vincent van Gogh lived 1886 to 1888 with his brother Theo. I remember looking up at the fourth-floor apartment. It was the first time I had so precisely connected a place and a person I was studying, gazing up like a lovelorn teen at a desired one’s room. Vincent looked out of that window! From the window in the back bedroom he painted the view of Paris! In the small studio he painted dozens of pictures I knew well. Each day Theo returned after a day’s work to the chaos that Vincent would have created.

From here one can follow Vincent. Down to the bvd de Clichy, where he attended Cormon’s academy and met Toulouse-Lautrec, Anquetin and Bernard, and at the Café Tambourin met Agostina Segatori, who modelled for him and with whom he had another of his chaotic liaisons, and where he showed his pictures. To the ave de Clichy, where he held a group exhibition. To the studios of painters, Toulouse-Lautrec, John Russell and Suzanne Valadon (now the Montmartre museum). Visiting the clubs and restaurants of Montmartre, including le Chat Noir, where Satie played, soliciting commissions for menu and signage design, unsuccessfully. Having been banned from painting in the street because of his disruptive behaviour, he climbed the Butte, to the Maquis and beyond, to the wild area and quarries that still surrounded the remaining windmills, and down to the Thiers wall around the city, and on to Asnières, where he met Seurat’s disciple, Signac.

In Paris he engaged at last with Impressionism. By coincidence he was in Paris for the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, and the last in 1886, and saw neither. But he saw their pictures at Boussod’s, where Theo worked, and other galleries and exhibitions.

And he met and was gradually accepted by the artists who would become the new avant-garde, Toulouse-Lautrec, Cézanne, Gauguin, Signac, Anquetin, Bernard. The ‘Artists of the Petits-Boulevards’, succeeding Manet, Money, Renoir, Degas, now ‘Artists of the Grands-Boulevards’.

I write of this transformative period in Vincent’s life in My Life with Van Gogh : Paris, accessed in the drop-down menu VINCENT & I. He arrived with a backward-looking body of work, left two years later prepared to produce his mature work in Arles, St-Rémy and Auvers.

Toulouse-Lautrec (born 1864) was the archetypal Montmartre artist. He studied for five years at Cormon’s studio on Bvd de Clichy, and lived the rest of his life in Montmartre. Family money paid for this fine studio, where he held his weekly soirées.

He was Suzanne Valadon’s lover for two years, giving her the name ‘Suzanne’, and encouraging her as both model and artist after a fall at the Circus Medrano (Bvd de Rochechouart) ended her career as an acrobat. I visited the museum devoted to him in Albi, on my cycle ride across France. (See ‘In Search of France’s Green Meridian’ in the drop down menu MY BOOKS, Day 19.) In this most comprehensive collection of his works, I was stunned by the quality of his art.

I learned this, from his ‘art works’ (painting, pastels etc): that he understood exactly the market of the late nineteenth-century city. Not the market for his paintings, but for what the subjects of his work were selling. (He refused to paint models, ‘stuffed dolls’ he called them.) His brothel scenes are shocking in their matter-of-factness. They are drained of all eroticism, allure. These are weary sex workers who, although they are between clients, are still working. And the work, their work, is inviting and then selling access to parts of their body. They dress, adopt poses, take on characters that will interest (‘arouse’ is too strong a word) the imagination of the client. They wait in positions they hope will invite his jaded attention. Each is trying to create a market, and thereby a buyer. There is something irremediably bleak about these pictures of girls selling the use (misuse) of their bodies, in a buyers’ market. I will remember this as I descend towards Ave de Clichy, ground zero of sex work.

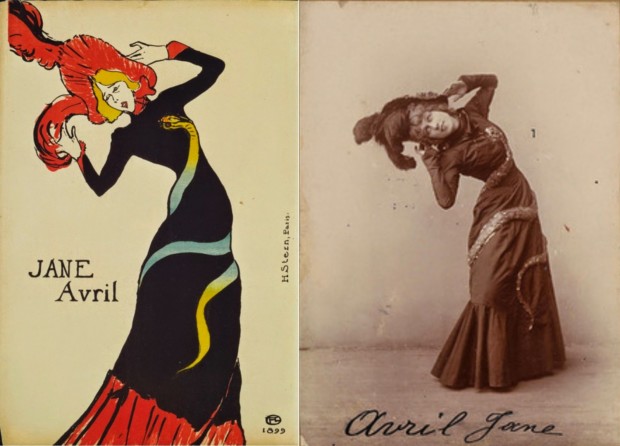

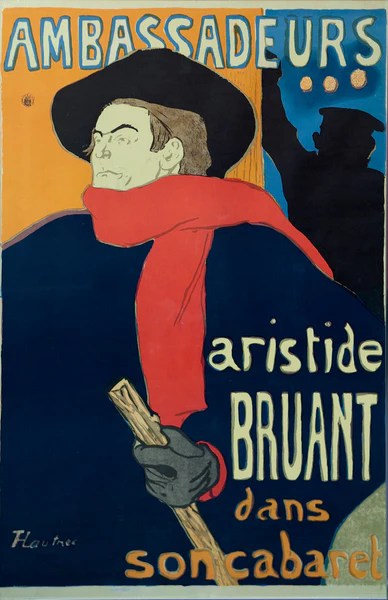

And I learned this, from his lithograph posters. By 1891 he was making iconic images to be reproduced as posters, to advertise bars, cabarets and, above all, artists. New laws allowed bars and cabarets to open, and a new freedom to put up posters. What care he took in, for example the posters he designed for Aristide Bruant, Jane Avril! In each, through many sketches, he works to create a very specific image, an iconic pose that captures, for the artist, their place, their niche in the market (their USP). As with the sex workers, he creates a representation of exactly what they are selling. Seen beside a photograph of the person, the poster is of the person, but more so.

Again, for each venue, the Moulin Rouge, the Folies Bergère, there is the sense of action caught at exactly the moment when … you want to, have to know more, what happens next. So, intrigued, the potential customer who sees the coloured image fly-posted on the wall has to go there, has to find out. Henri is the perfect ad man.

And also a great artist. Because at the same time as he is selling these images, he is showing the artifice, the frailty of the individual, the falseness of the situation. Reminding the viewer that this is not substance but image. He is the Warhol of his time.

(And I also like that, five-feet tall, disabled, he challenged to a duel Henry de Groux, for criticising Van Gogh. (Signac said, if Henri was killed, he would take up the sword. De Groux apologised and the duel didn’t take place.))

He died at 36, younger than Van Gogh, of alcoholism and syphilis.

Rue Lepic and around. Shops. Tapissier, Garnisseur, father and son, founded 1965, window stuffed with fabrics, fittings, fillings, obscuring the shop within. Old-fashioned looking, yet I might have been here when it opened. A tiny art gallery, white-painted and bare, on an easel in the window a detailed painting of a 1000€ banknote. A shop and workshop, Fabrique de Pantoufles. A stout door with multiple doorbells each with a name. (How many ring the bell of the fourth floor of 54 Rue Lepic …?) A florist, with bins of flowers on the pavement, its interior smelling of a Rousseau forest, with a spangled snake hanging from a vine. A memorial to the 500 Jewish children deported from the 18th arrondissement. A poster, like a fly-posting for a cat, for a lost unicorn, with a photograph, friendly, last seen etc, *Reward!*, and a phone number. A shop full of Perspex models, including a metre-high Eiffel Tower, 1755€. I remember the Perspex chess set I designed. Tourists. Parties led by flag-carrying guides, phones along the sides of the crocodile the eyes of Argos Panoptes. Serious (self-important) seekers on quests (me). A middle-aged couple, giddy with anticipation, looking for Dalida’s house. But this is a neighbourhood; the tourists are fish passing over a living coral reef. This is the neighbourhood of Amélie’s good deeds, the café is round the next corner. A thin woman, with long grey hair, in a patchwork coat and bright orange skirt, a small white dog in a shopping bag, talks shrilly to a large man, who listens sympathetically. Spinster? Divorcé? Widow? I see her climbing a curving stone staircase, hand on the loose bannister rail, to a single room overstuffed with her possessions. A slight, stoop-shouldered man, his hat at exactly the angle to look absurd, I imagine him living under his wife’s domination, he’s gone through life without a friend to tell him to alter, however slightly, the rake of his hat. He carries two-handed at midriff height a basket of vegetables, with a bunch of orange marigolds on the top. In the café, a pair of visiting tantes, handbags on their knees, expecting and receiving service as good as in their local café. A slim young man works at a laptop. And, how odd to write this, an ageing roué, once ruggedly handsome, gone fleshy with hanging jowls and dark rings around his eyes, sallow skin, grey hair drawn back into a pony tail (really?), leaning forward, talking urgently to a young man. A pick-up? His son? Don Juan as the Commendatore drags him down …? I have too little language, too little cultural context. And so I imagine. A boy and a girl roller-blade by, hand in hand, brother and sister, Cocteau’s enfants terribles. A street sprayer washes the cobbles, the light brightens and reflections multiply. Faces pass, and I want to fix, photograph each face, to pore over at night, discover, invent, reveal their lives, their stories. After two hours of directed walking, searching, looking, time slows, the world softens, becomes three-dimensional. And I slow, become absorbent, no longer a surface but a medium, in which stories precipitate and dissolve, as I walk in a favoured reverie of inner vision through all the intricacy of Montmartre.

I find myself in an odd triangular space, with a railing at the edge of a precipice and a long view over golden Paris. The precipice is one of the steep flights of steps that connect the contour-hugging roads.

By the railing a young man in a waistcoat and a cap, a cigarette at the corner of his mouth, sits at a small desk, in profile. On the desk is a manual typewriter, and a sign, ‘Poète Publique’.

A man comes and sits opposite him. As they talk the man leans forward. And suddenly the potency of the typewriter as a producer of unique documents lands in me. I see each letter inking on the ribbon and then impressing itself into the fibres of the paper, each tap a definitive event at an exact moment. Words on screen appear as if a mind is brushing the touch-soft keys; they float in space, universally transmissible, infinitely reproducible, outside time. This, the poem he is tapping onto the page – the paper moves to meet the descending letter! – here, now, may be copied, but it cannot be reproduced. Whether what he writes is a glib collection of pre-loaded phrases, like the portraits made in five minutes in the place du Tertre, or is a pure distillation – now! – of person, subject and the poet’s mind and poetic universe, is perfection, what he pulls from the machine – the distinctive zip of meshing cogs! – is uniquely here and now. The man walks across the space, reading intently.

(Perhaps it is because of the slipperiness of time in our phone universe that we are forever taking photographs – each with a time signature – to create a time line, and to reassure ourselves that there is, at least at the moment we take it, a present.)

But what is important in this place, in Place Emile Goudeau, is behind me, pressing against my back, insistent. I turn to face the Bateau-Lavoir.

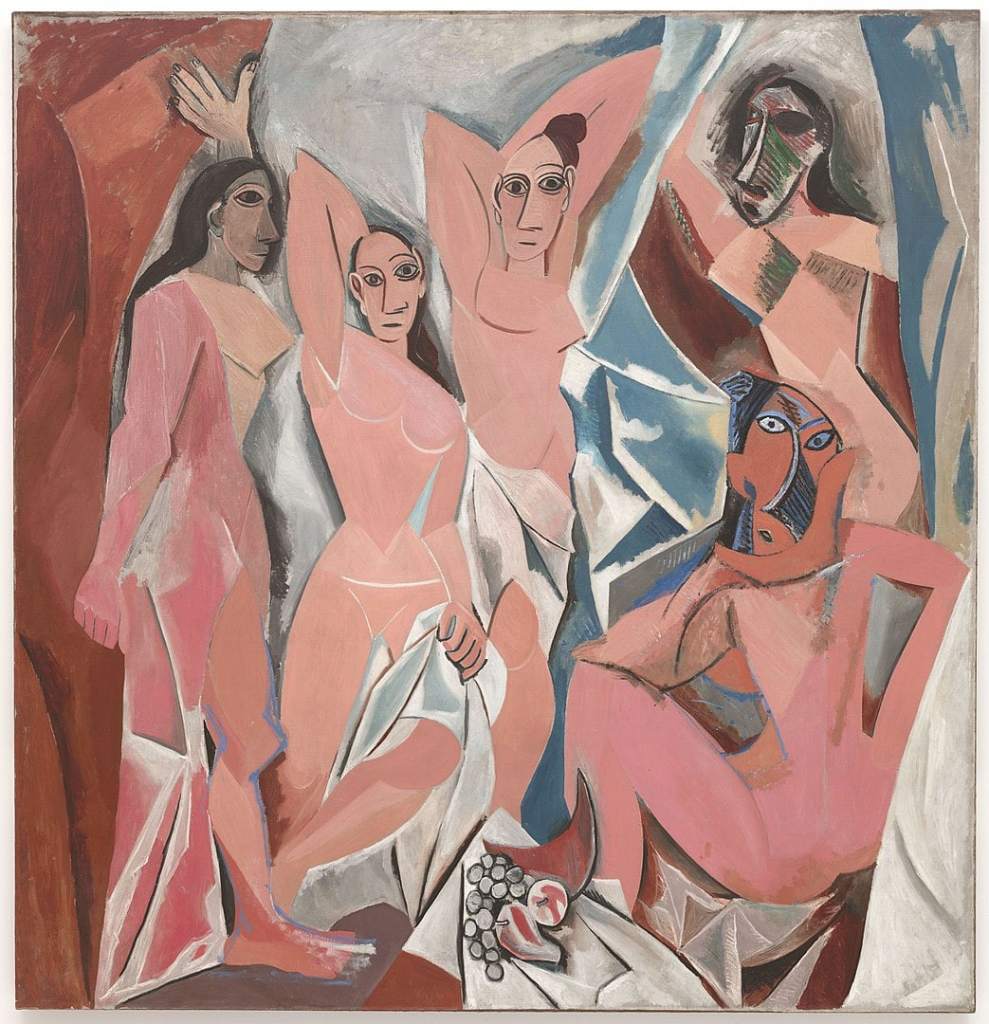

“We will return to the Bateau-Lavoir, the only place we will have been truly happy,” Picasso says, as if he is talking of a place to gather after death. In 1940s he visited here a toothless and destitute Germain Pichot, the woman in Au Lapin Agile, and left her money; “a memento mori,” commented Francoise Gilot, who was with him. His ‘brothel picture’ (his words) Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, outcome of six-months of nights of work at the Bateau-Lavois in 1907, he showed briefly and then, this exorcism that opened the way to inventing Cubism he kept hidden for ten years. He sold it, sight unseen for a tenth its value, as if transferring a fetish not a work of art. It was refused as a gift by the Louvre, purchased by the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1937, scraping the money together by selling a Degas. Hardly seen for 30 years, it was quickly acknowledged as the most significant painting of 1900s. With this single picture, Picasso replaced Matisse as leader of the avant-garde, and recruited Braque from Fauvism. Together, like climbers roped together, with first one then the other leading, they created Cubism.

It is a mesmerising picture. Over life size (8 feet by 7.5 feet), although it depicts five naked women in a brothel, subject to the gaze of both clients and viewers, it is their gaze that triumphs. “He replaced the benign ideal of the Classical nude with a new race of sexually assured and dangerous beings.” (Holland Cotter.) In life he dominated and drained women; in painting this picture, all his sexual fears were played out. He worked them through, exorcised them, in and into the picture. His work on the picture subdued his demons long enough to clear himself to embark on the invention of Cubism. A flat surface, without modulation, and yet compressed within it, saturating it, is the art of Cézanne and Gauguin (he saw their work in big exhibitions in 1906), Manet’s ‘Olympia’, Velazquez’ ‘Las Meninas’, El Greco’s ‘The Opening of the Fifth Seal’, African carving, primitive Iberian art … Compressed and yet separate, the flat surface contains within it the sense of four-dimensional space that is implicit in Cubism …

The Bateau-Lavoir had been a piano factory, derelict when it was cheaply divided into artists’ studios in 1890. It was given its name by Max Jacob, Picasso’s first friend in Paris, because its creaking and rocking in the wind reminded him of the laundry barges on the Seine. I had met the saintly Jacob (he is the monk in Picasso’s Three Musicians) in St-Benoit-sur-Loire on my cycle ride following la méridiènne verte where he was on retreat at the monastery when he was picked up in 1944 as a Jew (he had converted after a vision in 1909). He died before he could be transferred to Auschwitz. (See ‘In Search of France’s Green Meridian’ in the drop down menu MY BOOKS, Day 10.)

Picasso worked there from 1904 to 1911, living with Fernande Olivier, through his Blue and Pink periods, Demoiselles, and early Cubism. Having met Matisse and Braque at Gertrude Stein’s flat near The Luxembourg Gardens, he showed them Demoiselles in the Bateau. Matisse thought it a joke. Braque disliked it at first, but was won around. Displaced as leader of the avant-garde, while continuing to be a supremely fine artist, Matisse retreated to treating art as decorative, having “a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which provides relief for physical fatigue.”

In 1908 Picasso held a celebratory dinner for Douanier Rousseau at the Bateau. Mocked by many, Picasso admired his work, buying a picture from him. Rousseau announced, “we are the two most important artists of our time: you in the Egyptian style, me in the modern.” Apollinaire improvised, “You remember Rousseau, of the Aztec landscape / of the forests where mangoes and pineapples grew / of the monkeys that spilled the blood of melons / and of the blind emperor who was shot over there.” Everyone got very drunk.

“… the only place we will have been truly happy …”

After 1918 Picasso, and the centre of gravity of the avant-garde, moved across the river to Montparnasse.

I head south along the Meridian. Past Dalida’s house, where the couple stand hand in hand, in the presence, overwhelmed. She died here in 1987.

Graffiti ‘CHACHA I Heart U’ many times, obsessively sprayed down the street. I must write something on Paris graffiti.

A young couple parting, cool, talking as they separate, he stands, she backs away, going through the repertoire of posing, posturing, pleasing that I realise, when he finally lets her go and she turns and walks briskly away, girls habitually must do.

Entering Places des Abbesses, named for the monastery that owned this area before the Revolution. It is pretty much a perfect Paris square. Slender plane trees with peeling Jean Arp bark and fluttering leaves like green butterflies. Benches well filled. (Haussman put benches everywhere, to populate the streets and squares.) Oriental women with European children, nannies. A sixty-year old woman, immaculate, on the pavement on a scooter, scooting along, a stately entitlement. A woman parts from a man, he is grey-haired, knowingly handsome, she kisses him on the forehead, her fingers linger on his face, at last she turns and walks in my direction, getting older with each step. On the pavement a large pink man lies in a sleeping bag, naked upper body, Father Christmas, filling the pavement, everyone walks around him. Time to talk about French street furniture.

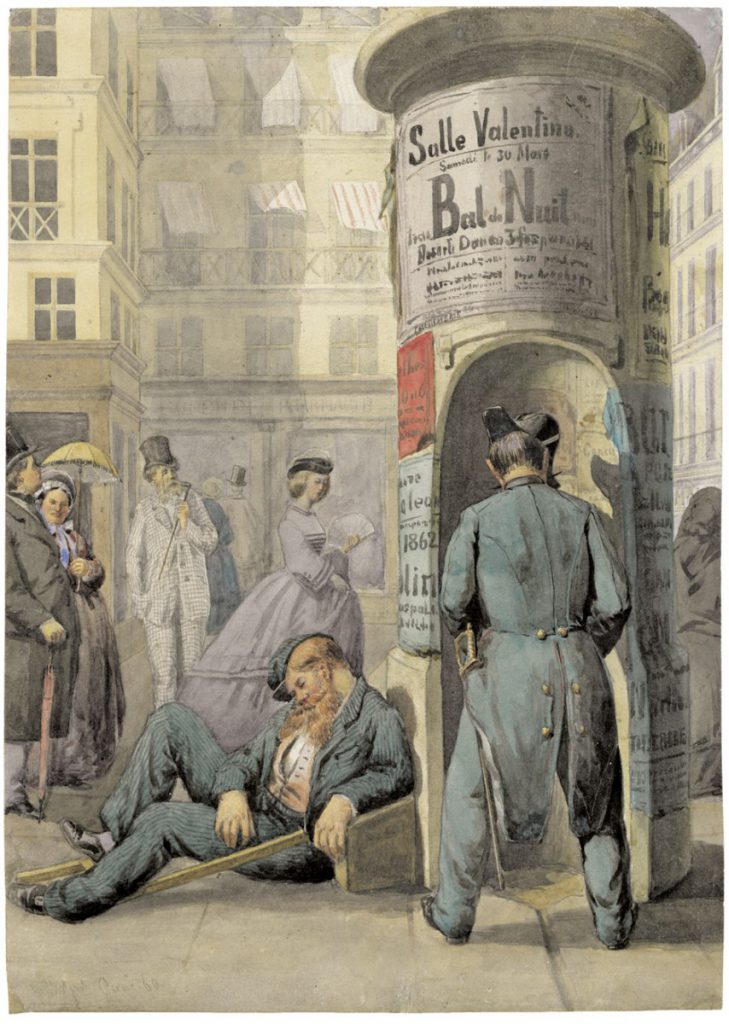

Street lights, benches, trees, sandy areas in the smallest triangles of public space, Morris columns, Wallace fountains, pissoirs and metro stations in the larger, were aspects of Haussmann’s aim to create safe shared public spaces, with minimal fencing, and safety reinforced by the eyes of surrounding shops and cafés. Each element was added incrementally, fitting in with their shared style of elaborate cast-ironwork and ‘Carriage Green’ paint.

Gas lights from 1840s, electric from 1870s.

Morris advertising columns (named after the first concessionaire) from 1868. The first advertising had used the walls of existing pissoirs; standalone columns were thought more appropriate. Now they are illuminated and often rotating.

Newspaper kiosks were added, as literacy grew and publications proliferated.

Wallace Fountains were donated by Richard, illegitimate son of the Marquis of Hertford. He lived most of his life in Paris, refused to leave during the siege in 1870, spending heavily on welfare. From 1872 his fountains provided free drinking water, and still do. One stands outside the Wallace Collection in London.

Metro stations from 1900. Although Paris was forty years behind London, by 1920 10 lines were operating. Noted for the short distance between stations, and the unified design of their entrances, by Hector Guimard in variations of a sinuous and elaborately organic Art Nouveau.

On the left is the entrance canopy at Abbesses, moved from Hotel de Ville in 1974. It is the highest station, 36 metres above the track. 176 steps down a spiral staircase, with murals covering the walls, and graffiti covering the murals. The trains on this line are fully automated, single sinuous snakes, with a seat and steering wheel at the front where ‘Children Only’ may drive. An oldish man playing an accordion, echoing off the white tiles, he’s very good. Twenty years ago he would have been paid to play in a bar. Forty years ago he’d have been in a band, making good money. Now he’s busking for coppers. Times change.

Facing the place is the church of St-Jean de Montmartre. Built 1894 – 1914 of reinforced concrete and steel, the first in France, contrary to building regulations and codes, threatened several times with demolition, it was classified an Historic Monument in 2014. A personal project of the priest, who wanted a church to serve lower Montmartre, he raised the money and appointed the architect. The information board celebrates the triumph of religious zeal over pettifogging bureaucracy. It is a a unique combination of Gothic and Art Nouveau.

I enter through carved doors, ‘you who suffer, you who struggle’. Inside it is spacious and yet dark. I experience a curious sense of contained holiness – or at least religiousness. A quiet seriousness that I associate with a friend. A young woman with long dark hair sits, looking at the altar, up at the window above the altar, not moving, in rapt concentration. She might be that friend. I look around, at the stained glass and murals and mosaics. I realise, as I circle around, through the arched spaces, that I don’t want to leave, I don’t want to go out into the light and busyness.

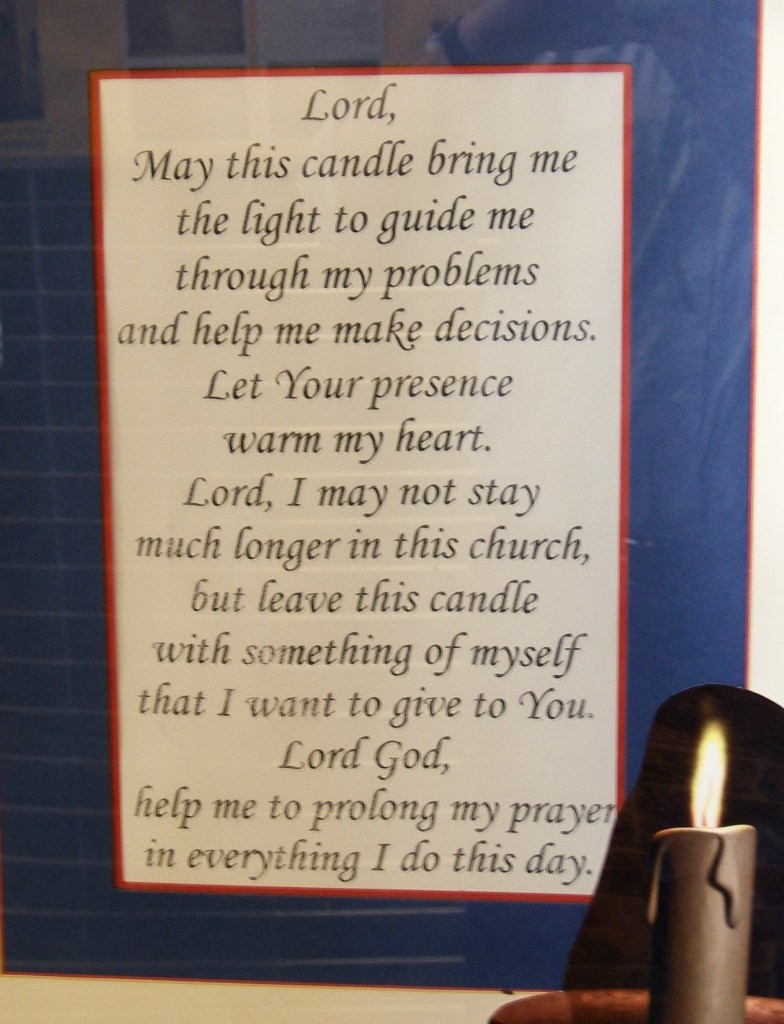

I photograph the prayer, which I will send to her. I light a candle for her. I thank her for revealing to me religious seriousness, even as I cannot share it. I am surprised at my religious sentimentality, touched by it. And at last, with thanks, I can return to the light and busyness, with a new quiet dark place inside me.

I walk down to Pigalle, cross Bvd de Clichy. Leaving the 18th arrodissement, I enter the 9th. I am in old Paris.

2 responses to “A Walk across Paris, along the Meridian : 3”

SATIE DAY MORNING

Saturday morning, Satie Day mourning,

One hundred years since Erik Satie died.

Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes sing out

Of my radio in celebration

Of a musical pioneer spirit.

A genius musical anarchist,

Parisian poet who set time free.

We can only dream of lost afternoons

Sat at piano dans Le Chat Noir

Avec La Goulou et Toulouse Lautrec,

Where Absinthe flowed as Debussey listened.

This doyen of Montmartre blew away

Conventions with Sports and Divertissements.

His freedom still echoes en Place Pigalles.

Harry Rogers, 28th June 2025

LikeLike

Great stuff! I really like your Song for Erik. Thanks for sharing. I think you’d have really found your place in Montmartre at that time! Keep on!!

LikeLiked by 1 person